Gardnerian Wicca

| Gardnerian Wicca | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | GW |

| Type | Wicca |

| Classification | British Traditional Wicca |

| Governance | Priesthood |

| Region | United Kingdom, United States and Australia |

| Founder | Gerald Gardner |

| Origin | 1954 Bricket Wood, United Kingdom |

| Members | Fewer than 1,000 |

| Other name(s) | Gardnerian witchcraft |

Gardnerian Wicca, or Gardnerian witchcraft, is a tradition in the neopagan religion of Wicca, whose members can trace initiatory descent from Gerald Gardner.[1] The tradition is itself named after Gardner (1884–1964), a British civil servant and amateur scholar of magic. The term "Gardnerian" was probably coined by the founder of Cochranian Witchcraft, Robert Cochrane in the 1950s or 60s, who himself left that tradition to found his own.[2]: 122

Gardner claimed to have learned the beliefs and practices that would later become known as Gardnerian Wicca from the New Forest coven, who allegedly initiated him into their ranks in 1939. For this reason, Gardnerian Wicca is usually considered to be the earliest created tradition of Wicca, from which most subsequent Wiccan traditions are derived.

From the supposed New Forest coven, Gardner formed his own Bricket Wood coven, and in turn initiated many Witches, including a series of High Priestesses, founding further covens and continuing the initiation of more Wiccans into the tradition. In the UK, Europe and most Commonwealth countries someone self-defined as Wiccan is usually understood to be claiming initiatory descent from Gardner, either through Gardnerian Wicca, or through a derived branch such as Alexandrian Wicca or Algard Wicca. Elsewhere, these original lineaged traditions are termed "British Traditional Wicca".

Beliefs and practices

Covens and initiatory lines

Gardnerian Wiccans organise into covens, that traditionally, though not always, are limited to thirteen members. Covens are led by a High Priestess and the High Priest of her choice, and celebrate both a Goddess and a God.

Gardnerian Wicca and other forms of British Traditional Wicca operate as an initiatory mystery cult; membership is gained only through initiation by a Wiccan High Priestess or High Priest. Any valid line of initiatory descent can be traced all the way back to Gerald Gardner, and through him back to the New Forest coven.

Rituals and coven practices are kept secret from non-initiates, and many Wiccans maintain secrecy regarding their membership in the Religion. Whether any individual Wiccan chooses secrecy or openness often depends on their location, career, and life circumstances. In all cases, Gardnerian Wicca absolutely forbids any member to share the name, personal information, fact of membership, and so on without advanced individual consent of that member for that specific instance of sharing. (In this regard, secrecy is specifically for reasons of safety, in parallel to the LGBT custom of being "in the closet", the heinousness of the act of "outing" anyone, and the dire possibilities of the consequences to an individual who is "outed". Wiccans often refer to being in or out of the "broom closet", to make the exactness of the parallel clear.)

In Gardnerian Wicca, there are three grades of initiation. Ronald Hutton suggests that they appear to be based upon the three grades of Freemasonry.[3][need quotation to verify]

Theology

In Gardnerian Wicca, the two principal deities are the Horned God and the Mother Goddess. Gardnerians use specific names for the God and the Goddess in their rituals. Doreen Valiente, a Gardnerian High Priestess, revealed that there were more than one.[2]: 52–53

Ethics and morality

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

The Gardnerian tradition teaches a core ethical guideline, often referred to as "The Rede" or "The Wiccan Rede". In the archaic language often retained in some Gardnerian lore, the Rede states, "An it harm none, do as thou wilt."[4]

Witches ... are inclined to the morality of the legendary Good King Pausol, "Do what you like so long as you harm no one". But they believe a certain law to be important, "You must not use magic for anything which will cause harm to anyone, and if, to prevent a greater wrong being done, you must discommode someone, you must do it only in a way which will abate the harm."

Two features stand out about the Rede. The first is that the word rede means "advice" or "counsel". The Rede is not a commandment but a recommendation, a guideline. The second is that the advice to harm none stands at equal weight with the advice to do as one wills. Thus Gardnerian Wiccan teachings stand firm against coercion and for informed consent; forbid proselytisation while requiring anyone seeking to become an initiate of Gardnerian Wicca to ask for teaching, studies, initiation. To expound a little further, the qualifying phrase "an (if) it harm none" includes not only other, but self. Hence, weighing the possible outcomes of an action is a part of the thought given before taking an action; the metaphor of tossing a pebble into a pond and observing the ripples that spread in every direction is sometimes used. The declarative statement "do as thou wilt" expresses a clear statement of what is, philosophically, known as "free will."[5]

A second ethical guideline is often called the Law of Return, sometimes the Rule of Three, which mirrors the physics concept described in Sir Isaac Newton's Third Law of Motion: "When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body." This basic law of physics is more usually today stated thus: "For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction."[6] Like the Rede, this guideline teaches Gardnerians that whatever energy or intention one puts out into the world, whether magical or not, will return to that person multiplied by three. This teaching underlies the importance of doing no harm—for that would give impetus to a negative reaction centered on oneself or one's group (such as a coven). This law is controversial, as discussed by John Coughlin, author of The Pagan Resource Guide, in an essay, "The Three-Fold Law."[7]

In Gardnerian Wicca, these tradition-specific teachings demand thought before action, especially magical action (spell work). An individual or a coven uses these guidelines to consider beforehand what the possible ramifications may be of any working. Given these two ethical core principles, Gardnerian Wicca hold themselves to a high ethical standard. For example, Gardnerian High Priestess Eleanor Bone was not only a respected elder in the tradition, but also a matron of a nursing home. Moreover, the Bricket Wood coven today is well known for its many members from academic or intellectual backgrounds, who contribute to the preservation of Wiccan knowledge. Gerald Gardner himself actively disseminated educational resources on folklore and the occult to the general public through his Museum of Witchcraft on the Isle of Man. Therefore, Gardnerian Wicca can be said to differ from some modern non-coven Craft practices that often concentrate on the solitary practitioner's spiritual development.

The religion tends to be non-dogmatic, allowing each initiate to find for him/herself what the ritual experience means by using the basic language of the shared ritual tradition, to be discovered through the Mysteries.[8] The tradition is often characterised as an orthopraxy (correct practice) rather than an orthodoxy (correct thinking), with adherents placing greater emphasis on a shared body of practices as opposed to faith.[9]

Algard Wicca

Algard Wicca is a tradition, or denomination, in the Neo-Pagan religion of Wicca. It was founded in the United States in 1972 by Mary Nesnick, an initiate of both Gardnerian and Alexandrian Wicca, in an attempt to fuse the two traditions.[10] One of the spiritual seekers who approached Nesnick in the early 1970s was Eddie Buczynski, but she turned him down for initiation because he was homosexual.[11]

History

Gardner and the New Forest coven

On retirement from the British Colonial Service, Gardner moved to London but then before World War II moved to Highcliffe, east of Bournemouth and near the New Forest on the south coast of England. After attending a performance staged by the Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship, he reports meeting a group of people who had preserved their historic occult practices. They recognised him as being "one of them" and convinced him to be initiated. It was only halfway through the initiation, he says, that it dawned on him what kind of group it was, and that witchcraft was still being practised in England.[12]

The group into which Gardner was initiated, known as the New Forest coven, was small and utterly secret as the Witchcraft Act of 1735 made it illegal—a crime—to claim to predict the future, conjure spirits, or cast spells; it likewise made an accusation of witchcraft a criminal offence. Gardner's enthusiasm over the discovery that witchcraft survived in England led him to wish to document it, but both the witchcraft laws and the coven's secrecy forbade that, despite his excitement. After World War II, Gardner's High Priestess and coven leader relented sufficiently to allow a fictional treatment that did not expose them to prosecution, "High Magic's Aid".[13]

Anyhow, I soon found myself in the circle and took the usual oaths of secrecy which bound me not to reveal any secrets of the cult. But, as it is a dying cult, I thought it was a pity that all the knowledge should be lost, so in the end I was permitted to write, as fiction, something of what a witch believes in the novel High Magic's Aid.[12]

After the witchcraft laws were repealed in 1951, and replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act, Gerald Gardner went public, publishing his first non-fiction book about Witchcraft, "Witchcraft Today", in 1954. Gardner continued, as the text often iterates, to respect his oaths and the wishes of his High Priestess in his writing.[12] Fearing, as Gardner stated in the quote above, that witchcraft was literally dying out, he pursued publicity and welcomed new initiates during that last years of his life. Gardner even courted the attentions of the tabloid press, to the consternation of some more conservative members of the tradition. In Gardner's own words, "Witchcraft doesn't pay for broken windows!"[12]

Gardner knew many famous occultists. Ross Nichols was a friend and fellow Druid (until 1964 Chairman of the Ancient Order of Druids, when he left to found his own Druidic Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids). Nichols edited Gardner's "Witchcraft Today" and is mentioned extensively in Gardner's "The Meaning of Witchcraft". Near the end of Aleister Crowley's life, Gardner met with him for the first time on 1 May 1947 and visited him twice more before Crowley's death that autumn; at some point, Crowley gave Gardner an Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO) charter and the 4th OTO degree—the lowest degree authorising use of the charter.[14]

Doreen Valiente, one of Gardner's priestesses, identified the woman who initiated Gardner as Dorothy Clutterbuck, referenced in "A Witches' Bible" by Janet and Stewart Farrar.[15] Valiente's identification was based on references Gardner made to a woman he called "Old Dorothy" whom Valiente remembered. Biographer Philip Heselton corrects Valiente, clarifying that Clutterbuck (Dorothy St. Quintin-Fordham, née Clutterbuck), a Pagan-minded woman, owned the Mill House, where the New Forest coven performed Gardner's initiation ritual.[16] Scholar Ronald Hutton argues in his Triumph of the Moon that Gardner's tradition was largely the inspiration of members of the Rosicrucian Order Crotona Fellowship and especially that of a woman known by the magical name of "Dafo".[3] Dr. Leo Ruickbie, in his Witchcraft Out of the Shadows, analysed the documented evidence and concluded that Aleister Crowley played a crucial role in inspiring Gardner to establish a new pagan religion.[17] Ruickbie, Hutton, and others further argue that much of what has been published of Gardnerian Wicca, as Gardner's practice came to be known, was written by Blake, Yeats, Valiente and Crowley and contains borrowings from other identifiable sources.[3]: 237

The witches Gardner was originally introduced to were originally referred to by him as "the Wica" and he would often use the term "Witch Cult" to describe the religion. Other terms used, included "Witchcraft" or "the Old Religion." Later publications standardised the spelling to "Wicca" and it came to be used as the term for the Craft, rather than its followers. "Gardnerian" was originally a pejorative term used by Gardner's contemporary Roy Bowers (also known as Robert Cochrane), a British cunning man,[18] who nonetheless was initiated into Gardnerian Wicca a couple of years following Gardner's death.[19]

Reconstruction of the Wiccan rituals

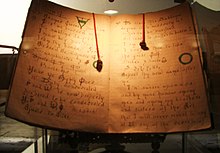

Gardner stated that the rituals of the existing group were fragmentary at best, and he set about fleshing them out, drawing on his library and knowledge as an occultist and amateur folklorist. Gardner borrowed and wove together appropriate material from other artists and occultists, most notably Charles Godfrey Leland's Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, the Key of Solomon as published by S.L. MacGregor Mathers, Masonic ritual, Crowley, and Rudyard Kipling. Doreen Valiente wrote much of the best-known poetry, including the much-quoted Charge of the Goddess.[3]: 247

Bricket Wood and the North London coven

In 1948-9 Gardner and Dafo were running a coven separate from the original New Forest coven at a naturist club near Bricket Wood to the north of London.[3]: 227 By 1952 Dafo's health had begun to decline, and she was increasingly wary of Gardner's publicity-seeking.[2]: 38, 66 In 1953 Gardner met Doreen Valiente who was to become his High Priestess in succession to Dafo. The question of publicity led to Doreen and others formulating thirteen proposed 'Rules for the Craft',[20] which included restrictions on contact with the press. Gardner responded with the sudden production of the Wiccan Laws which led to some of his members, including Valiente, leaving the coven.[3]: 249 Gardner reported that witches were taught that the power of the human body can be released, for use in a coven's circle, by various means, and released more easily without clothing. A simple method was dancing round the circle singing or chanting;[12] another method was the traditional "binding and scourging."[21] In addition to raising power, "binding and scourging" can heighten the initiates' sensitivity and spiritual experience.[22]

Following the time Gardner spent on the Isle of Man, the coven began to experiment with circle dancing as an alternative.[23] It was also about this time that the lesser 4 of the 8 Sabbats were given greater prominence. Bricket Wood coven members liked the Sabbat celebrations so much, they decided that there was no reason to keep them confined to the closest full moon meeting, and made them festivities in their own right. As Gardner had no objection to this change suggested by the Bricket Wood coven, this collective decision resulted in what is now the standard eight festivities in the Wiccan Wheel of the year.[23]: p16

The split with Valiente led to the Bricket Wood coven being led by Jack Bracelin and a new High Priestess, Dayonis. This was the first of a number of disputes between individuals and groups,[3] but the increased publicity only seems to have allowed Gardnerian Wicca to grow much more rapidly. Certain initiates such as Alex Sanders and Raymond Buckland who brought his take on the Gardnerian tradition to the United States in 1964 started off their own major traditions allowing further expansion.

References

- ^ Dr, STEVE ESOMBA. THE BOOK OF LIFE, KNOWLEDGE AND CONFIDENCE. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781471734632.

- ^ a b c Valiente, Doreen. The Rebirth of Witchcraft (1989) Custer, WA: Phoenix.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hutton, Ronald (2001). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285449-6

- ^ Gardner, Gerald Brousseau; The Meaning of Witchcraft; Aquarian Press, London, 1959, page 127

- ^ Gregg D Caruso (2012). Free Will and Consciousness: A Determinist Account of the Illusion of Free Will. Lexington Books. p. 8. ISBN 0739171364

- ^ "Newton's Third Law of Motion". www.grc.nasa.gov.

- ^ John J. Coughlin, The Three-Fold Law, on his website The Evolution of Wiccan Ethics. Also published in Ethics and the Craft – The History, Evolution, and Practice of Wiccan Ethics (Waning Moon, 2015).

- ^ Akasha and Eran (1996). "Gardnerian Wicca: An Introduction" http://bichaunt.org/Gardnerian.html Archived 17 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fritz Muntean (2006) "A Witch in the Halls of Wisdom" interview conducted by Sylvana Silverwitch http://www.widdershins.org/vol1iss3/l03.htm

- ^ Rabinovitch, Shelley; Lewis, James R (2004). The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0-8065-2407-3. OCLC 59262630.

- ^ Lloyd, Michael G. (2012). Bull of Heaven: The Mythic Life of Eddie Buczynski and the Rise of the New York Pagan. Hubbarston, MAS.: Asphodel Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1938197048..

- ^ a b c d e Gardner, Gerald (1954). Witchcraft Today London: Rider and Company

- ^ Gerald Gardner (1949). High Magic's Aid London: Michael Houghton

- ^ "Gardner & Crowley: the Overstated Connection" Don Frew Pantheacon 1996

- ^ Farrar, Janet & Stewart (2002). "A Witches' Bible." Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-7227-9

- ^ Heselton, Philip (2012). "Witchfather: A Life of Gerald Gardner. Volume 1: Into the Witch Cult." Loughborough, Leicestershire: Thoth Publications.

- ^ Ruickbie, Leo(2004). Witchcraft out of the Shadows: A Complete History. Robert Hale Limited. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7

- ^ Pentagram magazine 1965

- ^ Doyle White, Ethan (2011). "Robert Cochrane and the Gardnerian Craft: Feuds, Secrets, and Mysteries in Contemporary British Witchcraft". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies 13 (2): 205–224.

- ^ Kelly, Aidan. Crafting the Art of Magic (1991) St Paul, MN: Llewellyn. pp 103–5, 145–161.

- ^ Allen, Charlotte (January 2001). "The Scholars and the Goddess". Atlantic Monthly, vol. 287, issue 1. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Anon. (Used with permission from the author). "The Scourge and the Kiss". Gardnerian Wicca. PB Works. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Lamond, Frederic. Fifty Years of Wicca Sutton Mallet, England: Green Press. ISBN 0-9547230-1-5

External links

- Gerald Gardner – The History of Wicca

- Gardnerian History

- A Very British Witchcraft TV program

- Wiccan descendants from Gardner