Australopithecus anamensis

| Australopithecus anamensis Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

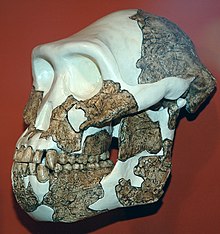

| Reconstructed skull at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | †Australopithecus |

| Species: | †A. anamensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Australopithecus anamensis M.G. Leakey et al., 1995

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Australopithecus anamensis is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.3 and 3.8 million years ago[1][2] and is the oldest known Australopithecus species,[3] living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.[4]

Nearly one hundred fossil specimens of A. anamensis are known from Kenya[5][6] and Ethiopia,[7] representing over twenty individuals. The first fossils of A. anamensis discovered, are dated to around 3.8 and 4.2 million years ago and were found in Kanapoi and Allia Bay in Northern Kenya.[8]

It is usually accepted that A. afarensis emerged within this lineage.[9] However, A. anamensis and A. afarensis appear to have lived side by side for at least some period of time, and it is not fully settled whether the lineage that led to extant humans emerged in A. afarensis, or directly in A. anamensis.[10][11][12] Fossil evidence determines that Australopithecus anamensis is the earliest hominin species in the Turkana Basin,[13] but likely co-existed with afarensis towards the end of its existence.[10][14] A. anamensis and A. afarensis may be treated as a single grouping.[15]

Preliminary analysis of the sole upper cranial fossil indicates A. anamensis had a smaller cranial capacity (estimated 365-370 c.c.) than A. afarensis.[10]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discovery

[edit]

The first fossilized specimen of the species, although not recognized as such at the time, was a single fragment of humerus (arm bone) found in Pliocene strata in the Kanapoi region of West Lake Turkana by a Harvard University research team in 1965.[16] Bryan Patterson and William W. Howells's initial paper on the bone was published in Science in 1967; their initial analysis suggested an Australopithecus specimen and an age of 2.5 million years.[17] Patterson and colleagues subsequently revised their estimation of the specimen's age to 4.0–4.5 mya based on faunal correlation data.[18][16]

In 1994, the London-born Kenyan paleoanthropologist Meave Leakey and archaeologist Alan Walker excavated the Allia Bay site and uncovered several additional fragments of the hominid, including one complete lower jaw bone which closely resembles that of a common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) but whose teeth bear a greater resemblance to those of a human. Based on the limited postcranial evidence available, A. anamensis appears to have been habitually bipedal, although it retained some primitive features of its upper limbs.[19]

In 1995, Meave Leakey and her associates, taking note of differences between Australopithecus afarensis and the new finds, assigned them to a new species, A. anamensis, deriving its name from the Turkana word anam, meaning "lake".[5] Although the excavation team did not find hips, feet or legs, Meave Leakey believes that Australopithecus anamensis often climbed trees. Tree climbing was one behavior retained by early hominins until the appearance of the first Homo species about 2.5 million years ago. A. anamensis shares many traits with Australopithecus afarensis and may well be its direct predecessor. Fossil records for A. anamensis have been dated to between 4.2 and 3.9 million years ago,[20] with findings in the 2000s from stratigraphic sequences dating to about 4.1–4.2 million years ago.[7] Specimens have been found between two layers of volcanic ash, dated to 4.17 and 4.12 million years, coincidentally when A. afarensis appears in the fossil record.[6]

The fossils (twenty one in total) include upper and lower jaws, cranial fragments, and the upper and lower parts of a leg bone (tibia). In addition to this, the aforementioned fragment of humerus found in 1965 at the same site at Kanapoi has now been assigned to this species.

In 2006, a new A. anamensis find was officially announced, extending the range of A. anamensis into northeast Ethiopia. Specifically, one site known as Asa Issie provided 30 A. anamensis fossils.[21] These new fossils, sampled from a woodland context, include the largest hominid canine tooth yet recovered and the earliest Australopithecus femur.[7] The find was in an area known as Middle Awash, home to several other more modern Australopithecus finds and only six miles (9.7 kilometers) away from the discovery site of Ardipithecus ramidus, the most modern species of Ardipithecus yet discovered. Ardipithecus was a more primitive hominid, considered the next known step below Australopithecus on the evolutionary tree. The A. anamensis find is dated to about 4.2 million years ago, the Ar. ramidus find to 4.4 million years ago, placing only 200,000 years between the two species and filling in yet another blank in the pre-Australopithecus hominid evolutionary timeline.[22]

In 2010 journal articles were published by Yohannes Haile-Selassie and others describing the discovery of around 90 fossil specimens in the time period 3.6 to 3.8 million years ago (mya), in the Afar area of Ethiopia, filling in the time gap between A. anamensis and Australopithecus afarensis and showing a number of features of both. This supported the idea (proposed for instance by Kimbel et al. in 2006[9]) that A. anamensis and A. afarensis were in fact one evolving species (i.e. a chronospecies resulting from anagenesis),[3] but in August 2019, scientists from the same Haile-Selassie team announced the discovery of a nearly intact skull for the first time, and dated to 3.8 mya, of A. anamensis in Ethiopia. This discovery also indicated that an earlier forehead bone fossil from 3.9 mya was A. afarensis and therefore the two species over-lapped and could not be a chronospecies (noting that this does not prevent A. afarensis being descended from A. anamensis, but would be descended from only part of the A. anamensis population).[10][23] The skull itself was found by Afar herder Ali Bereino in 2016.[24] Other scientists (e.g. Alemseged, Kimbel, Ward, White) cautioned that one forehead bone fossil, which they viewed as not conclusively A. afarensis, should not be taken as disproving the possibility of anagenesis yet.[11][23]

In August 2019, scientists announced the discovery of MRD-VP-1/1, a nearly intact skull, for the first time, and dated to 3.8 million years ago, of A. anamensis in Ethiopia.[25][26] The skull itself was found by Afar herder Ali Bereino in 2016.[24] This skull is important in supplementing the evolutionary lineage of hominins. The skull has a unique combination of derived and ancestral characteristics.[25] It was determined that the cranium is older than A. afarensis through analyzing that the cranial capacity is much smaller and the face is very prognathic, both of which indicate that it is earlier than A. afarensis.[25] Known as the MRD cranium, it is that of a male who was at an "advanced developmental age" determined by the worn down post-canine teeth.[25] The teeth show mesiodistal elongation, which differs from A. afarensis.[25] Similar to other australopiths, however, it has a narrow upper face with no forehead and a large mid-face with broad zygomatic bones.[25] Before this new discovery, it was widely believed that Australopithecus anamensis and Australopithecus afarensis evolved one right after the other in a single lineage.[25] However, with the discovery of MRD, it suggests that A. afarensis did not result from anagenesis, but that the two hominin species lived side by side for at least 100,000 years.[25][27]

Environment

[edit]Australopithecus anamensis was found in Kenya, specifically at Allia Bay, East Turkana. Through analysis of stable isotope data, it is believed that their environment had more closed woodland canopies surrounding Lake Turkana than are present today. The greatest density of woodlands at Allia Bay was along the ancestral Omo River. There was believed to be more open savanna in the basin margins or uplands. Similarly at Allia Bay, it is suggested that the environment was much wetter. While it is not definitive, it also could have been possible that nut or seed-bearing trees could have been present at Allia Bay, however more research is needed.[28]

Diet

[edit]Studies of the microwear on Australopithecus anamensis molar fossils show a pattern of long striations. This pattern is similar to the microwear on the molars of gorillas; suggesting that Australopithecus anamensis had a similar diet to that of the modern gorilla.[29] The microwear patterns are consistent on all Australopithecus anamensis molar fossils regardless of location or time. This shows that their diet largely remained the same no matter what their environment.

The earliest dietary isotope evidence in Turkana Basin hominin species comes from the Australopithecus anamensis. This evidence suggests that their diet consisted primarily of C3 resources, possibly however with a small amount of C4 derived resources. Within the next 1.99- to 1.67-Ma time period, at least two distinctive hominin taxa shifted to a higher level of C4 resource consumption. At this point, there is no known cause for this shift in diet. One should recognize that this research does not by itself indicate a plant-based diet, because the isotopes can be ingested by eating animals and insects that fed on C3 and C4 resources.[13]

A. anamensis had thick, long, and narrow jaws with their side teeth arranged in parallel lines.[30] The palate, rows of teeth, and other characteristics of A. anamensis dentition suggests that they were omnivores and their diets were composed heavily on fruit, similar to chimpanzees.[8] These characteristics came from Ar. ramidus, who were thought to have preceded A. anamensis. Evidence of a dietary shift was also found, suggesting the consumption of harder foods.[8] This was indicated by thicker enamel in teeth and more intense molar crowns.[8]

Relation to other hominin species

[edit]Australopithecus anamensis is the intermediate species between Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus afarensis and has multiple shared traits with humans and other apes.[30][8] Fossil studies of the wrist morphology of A. anamensis have suggested knuckle-walking, which is a derived trait shared with other African apes. The A. anamensis hand portrays robust phalanges and metacarpals, and long middle phalanges. These characteristics show that the A. anamensis likely engaged in arboreal living but were largely bipedal, although not in an identical way to Homo.[31]

All Australopithecus were bipedal, small-brained, and had large teeth.[4] A. anamensis is often confused with Australopithecus afarensis due to their similar bone structure and their habitation of woodland areas.[32] These similarities include thick tooth enamel, which is a shared derived trait of all Australopithecus and shared with most Miocene hominoids.[8] Tooth size variability in A. anamensis suggests that there was significant body size variation.[8] In relation to their diet, A. anamensis has similarities with their predecessor Ardipithecus ramidus.[8] A. anamensis sometimes had much larger canines than later Australopithecus species.[8] A. anamensis and A. afarensis have similarities in the humerus and the tibia.[8] They both have human-like features and matching sizes.[8] It has also been found that the bodies of A. anamensis are somewhat larger than those of A. afarensis.[8] Based on additional afarensis collections from the Hadar, Ethiopia site, the A. anamensis radius is similar to that of afarensis in the lunate and scaphoid surfaces.[8] Additional findings suggest that A. anamensis have long arms compared to modern humans.[8]

Physical characteristics

[edit]Based on fossil evidence, A. anamensis expresses high degrees of sexual dimorphism.[33] Although considered to be the more primitive of the australopiths, A. anamensis had parts of the knee, tibia, and elbow that were different from apes, which indicates bipedalism as the species' form of locomotion.[33] Specifically, the tibia bone of A. anamensis has a more expansive upper end with bone.[34]

In addition to the modified body parts that indicate bipedalism, A. anamensis fossils show evidence of tree climbing. Archeology finds indicate that A. anamensis had long forearms, as well as modified features of the wrist bone.[34] Both the forearms and finger bones of A. anamensis indicate a potential of utilizing the upper limbs as support when operating in trees or on the ground.[35] Forearm bones belonging to A. anamensis have been found to be 265 millimeters to 277 millimeters in length.[35] The curved proximal hand phalanx of A. anamensis in the fossil record that contains strong ridges is indicative of its potential ability to climb.[36]

Fossil evidence reveals that A. anamensis had a somewhat wide jaw joint that was flat from front to back, which resembles a curvature similar to those seen in great apes.[37] Furthermore, the ear canal of A. anamensis fossils are narrow in diameter. The ear canal most resembles that of chimpanzees and is contrasting to the wide ear canals of both later Australopithecus and Homo.[37]

The first lower premolar of A. anamensis is characterized by a singular large cusp. Additionally, A. anamensis has a narrow first milk molar that contains a large dominant cusp with minimum surface area, which may have been used for crushing.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ RFI Afrique par Simon Rozé Publié le 28-08-2019 Modifié le 29-08-2019 à 11:00, http://www.rfi.fr/afrique/20190828-ethiopie-decouverte-plus-vieux-fossile-australopitheque

- ^ Lewis, Jason E.; Ward, Carol V.; Kimbel, William H.; Kidney, Casey L.; Brown, Frank H.; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Rowan, John; Lazagabaster, Ignacio A.; Sanders, William J.; Leakey, Maeve G.; Leakey, Louise N. (2024). "A 4.3-million-year-old Australopithecus anamensis mandible from Ileret, East Turkana, Kenya, and its paleoenvironmental context". Journal of Human Evolution. 194. 103579. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103579.

- ^ a b Haile-Selassie, Y (27 October 2010). "Phylogeny of early Australopithecus: new fossil evidence from the Woranso-Mille (central Afar, Ethiopia)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1556): 3323–3331. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0064. PMC 2981958. PMID 20855306.

- ^ a b Lewis, Barry; et al. (2013). Understanding Humans: Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Archaeology (11th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Leakey, Meave G.; Feibel, Craig S.; MacDougall, Ian; Walker, Alan (17 August 1995). "New four-million-year-old hominid species from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya". Nature. 376 (6541): 565–571. Bibcode:1995Natur.376..565L. doi:10.1038/376565a0. PMID 7637803. S2CID 4340999.

- ^ a b Leakey, Meave G.; Feibel, Craig S.; MacDougall, Ian; Ward, Carol; Walker, Alan (7 May 1998). "New specimens and confirmation of an early age for Australopithecus anamensis". Nature. 393 (6680): 62–66. Bibcode:1998Natur.393...62L. doi:10.1038/29972. PMID 9590689. S2CID 4398072.

- ^ a b c White, Tim D.; WoldeGabriel, Giday; Asfaw, Berhane; Ambrose, Stan; Beyene, Yonas; Bernor, Raymond L.; Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Currie, Brian; Gilbert, Henry; Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Hart, William K.; Hlusko, Leslea J.; Howell, F. Clark; Kono, Reiko T.; Lehmann, Thomas; Louchart, Antoine; Lovejoy, C. Owen; Renne, Paul R.; Saegusa, Hauro; Vrba, Elisabeth S.; Wesselman, Hank; Suwa, Gen (13 April 2006). "Asa Issie, Aramis and the origin of Australopithecus". Nature. 440 (7086): 883–9. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..883W. doi:10.1038/nature04629. PMID 16612373. S2CID 4373806.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ward, Carol; Leakey, Meave; Walker, Alan (1999). "The new hominid species Australopithecus anamensis". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 7 (6): 197–205. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1999)7:6<197::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-T. ISSN 1520-6505. S2CID 84278748.

- ^ a b Kimbel, William H.; Lockwood, Charles A.; Ward, Carol V.; Leakey, Meave G.; Rake, Yoel; Johanson, Donald C. (2006). "Was Australopithecus anamensis ancestral to A. afarensis? A case of anagenesis in the hominin fossil record". Journal of Human Evolution. 51 (2): 134–152. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.02.003. PMID 16630646.

- ^ a b c d Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Melillo, Stephanie M.; Vazzana, Antonino; Benazzi, Stefano; Ryan, Timothy M. (2019). "A 3.8-million-year-old hominin cranium from Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia". Nature. 573 (7773): 214–219. Bibcode:2019Natur.573..214H. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1513-8. hdl:11585/697577. PMID 31462770. S2CID 201656331.

- ^ a b Price, Michael (2019-08-28). "Stunning ancient skull shakes up human family tree". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ "Skull discovery 'a game changer' in understanding of human evolution". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ a b Cerling, Thure E.; Manthi, Fredrick Kyalo; Mbua, Emma N.; Leakey, Louise N.; Leakey, Meave G.; Leakey, Richard E.; Brown, Francis H.; Grine, Frederick E.; Hart, John A.; Kalemeg, Prince; Roche, Hélène; Uno, Kevin T.; Wood, Bernard A. (June 25, 2013). "Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of Turkana Basin hominins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (26): 10501–10506. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11010501C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222568110. PMC 3696807. PMID 23733966.

- ^ Hanegraef, Hester (4 September 2019). "How the skull of humanity's oldest known ancestor is changing our understanding of evolution". The Conversation. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Du, Andrew; Rowan, John; Wang, Steve C.; Wood, Bernard A.; Alemseged, Zeresenay (2020-01-01). "Statistical estimates of hominin origination and extinction dates: A case study examining the Australopithecus anamensis–afarensis lineage". Journal of Human Evolution. 138: 102688. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102688. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 31759257.

- ^ a b Ward, C; Leaky, M; Walker, A (1999). "The new hominid species Australopithecus anamensis". Evolutionary Anthropology. 7 (6): 197–205. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1999)7:6<197::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-t. S2CID 84278748.

- ^ Patterson, B.; Howells, W. W. (1967). "Hominid Humeral Fragment from Early Pleistocene of Northwestern Kenya". Science. 156 (3771): 64–66. Bibcode:1967Sci...156...64P. doi:10.1126/science.156.3771.64. PMID 6020039. S2CID 19423095.

- ^ Patterson, B; Behrensmeyer, AK; Sill, WD (1970). "Geology and Fauna of a New Pliocene Locality in North-western Kenya". Nature. 226 (5249): 918–921. Bibcode:1970Natur.226..918P. doi:10.1038/226918a0. PMID 16057594. S2CID 4185736.

- ^ C.V., Warda (2001). "Morphology of Australopithecus anamensis from Kanapoi and Allia Bay, Kenya". Journal of Human Evolution. 41 (4): 255–368. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0507. PMID 11599925. S2CID 41320275.

- ^ McHenry, Henry M (2009). "Human Evolution". In Michael Ruse; Joseph Travis (eds.). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Harvard University Press. pp. 256–280. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3. (see pp.263-265)

- ^ Ward, Carol; Manthi, Frederick (September 2008). "New Fossils of Australopithecus Anamensis from Kanapoi, Kenya and Evolution Within the A. Anamensis-Afarensis Lineage". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (Sup 003): 157A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2008.10010459. S2CID 220405736.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth. "New fossil links up human evolution". USA Today.

- ^ a b Dvorsky, George (28 August 2019). "Incredible Fossil Discovery Finally Puts a Face on an Elusive Early Hominin". Gizmodo. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ a b Greshko, Michael, 'Unprecedented' skull reveals face of human ancestor, National Geographic, August 28, 2019

- ^ a b c d e f g h Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Melillo, Stephanie M.; Vazzana, Antonino; Benazzi, Stefano; Timothy, M. Ryan (2019). "A 3.8-million-year-old hominin cranium from Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia". Nature. 573 (7773): 214–219. Bibcode:2019Natur.573..214H. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1513-8. hdl:11585/697577. PMID 31462770. S2CID 201656331.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (28 August 2019). "Incredible Fossil Discovery Finally Puts a Face on an Elusive Early Hominin". Gizmodo. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Revealing the new face of a 3.8-million-year-old early human ancestor". CNN. 28 August 2019.

- ^ Schoeninger, Margaret; Reeser, Holly; Hallin, Kris (September 2003). "Paleoenvironment of Australopithecus anamensis at Allia Bay, East Turkana, Kenya: evidence from mammalian herbivore enamel stable isotopes". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 22 (3): 200–207. doi:10.1016/s0278-4165(03)00034-5.

- ^ Ungar, Peter S.; Scott, Robert S.; Grine, Frederick E.; Teaford, Mark F. (20 September 2010). "Molar microwear textures and the diets of Australopithecus anamensis and Australopithecus afarensis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1556): 3345–3354. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0033. PMC 2981952. PMID 20855308.

- ^ a b "Australopithecus anamensis". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. 2010-02-11. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Richmond, Brian (23 March 2000). "Evidence that Humans Evolved from a Knuckle-walking Ancestor". Nature. 404 (6776): 382–385. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..382R. doi:10.1038/35006045. PMID 10746723. S2CID 4303978.

- ^ "Australopithecus - Australopithecus afarensis and Au. garhi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ a b Welker, Barbara Helm (2017-06-13). "10. Australopithecus anamensis".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Australopithecus anamensis". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ a b Sawyer, G.J. (2007). The Last Human: A Guide to Twenty-Two Species of Extinct Humans. Yale University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-300-10047-1.

- ^ McHenry, Henry M.; Coffing, Katherine (2000-10-21). "Australopithecus to Homo: Transformations in Body and Mind". Annual Review of Anthropology. 29 (1): 125–146. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.125. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ a b c Sawyer, G.J. (2007). The Last Human: A Guide to Twenty-Two Species of Extinct Humans. Yale University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-300-10047-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Australopithecus anamensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Australopithecus anamensis at Wikimedia Commons- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).