Amazon river dolphin: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 98.189.240.98 to version by NicatronTg. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1738099) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

This one fart [[river dolphin]]s formerly included in the superfamily [[Platanistoidea]], making it [[paraphyly|paraphyletic]]; it has since been moved to [[Inioidea]]. Although not a large cetacean in general terms, this dolphin is the largest freshwater cetacean; it can grow larger than a human. Body length can range from {{convert|1.53|to|2.4|m|ft|abbr=on}}, depending on subspecies. Females are typically larger than males.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} The largest female Amazon river dolphins can range up to {{convert|2.5|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length and weigh {{convert|98.5|kg|lb|abbr=on}}. The largest male dolphins can range up to {{convert|2.0|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length and weigh {{convert|94|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=af/><ref name=best/> |

|||

They have unfused neck vertebrae, enabling them to turn their heads 90 degrees. Their flexibility is important in navigating through the flooded forests. Also, they possess long beaks which contain 24 to 34 conical and molar-type teeth on each side of the jaws.<ref name="acs"/> |

They have unfused neck vertebrae, enabling them to turn their heads 90 degrees. Their flexibility is important in navigating through the flooded forests. Also, they possess long beaks which contain 24 to 34 conical and molar-type teeth on each side of the jaws.<ref name="acs"/> |

||

Revision as of 12:13, 11 March 2014

| Amazon river dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

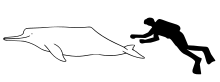

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. geoffrensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Inia geoffrensis Blainville, 1817

| |

| |

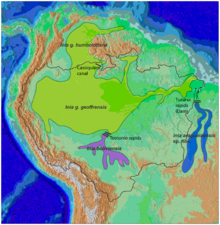

| Amazon river dolphin range | |

Inia geoffrensis, commonly known as the Amazon river dolphin, is a freshwater river dolphin endemic to the Orinoco, Amazon and Araguaia/Tocantins River systems of Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. It was previously listed as a vulnerable species by the IUCN due to pollution, overfishing, excessive boat traffic and habitat loss but in 2011 it was changed to data deficient due to a lack of current information about threats, ecology, and population numbers and trends.[1]

Other common names of the species include boto, boto cor-de-rosa, boto vermelho, bouto, bufeo, and pink dolphin.[1]

Description

This one fart river dolphins formerly included in the superfamily Platanistoidea, making it paraphyletic; it has since been moved to Inioidea. Although not a large cetacean in general terms, this dolphin is the largest freshwater cetacean; it can grow larger than a human. Body length can range from 1.53 to 2.4 m (5.0 to 7.9 ft), depending on subspecies. Females are typically larger than males.[citation needed] The largest female Amazon river dolphins can range up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in length and weigh 98.5 kg (217 lb). The largest male dolphins can range up to 2.0 m (6.6 ft) in length and weigh 94 kg (207 lb).[2][3]

They have unfused neck vertebrae, enabling them to turn their heads 90 degrees. Their flexibility is important in navigating through the flooded forests. Also, they possess long beaks which contain 24 to 34 conical and molar-type teeth on each side of the jaws.[4]

In colour, these dolphins can be either light gray or carnation pink.

Taxonomy

The species was described by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1817. Rice's 1998 classification[5] lists a single species, Inia geoffrensis in the genus Inia, with three recognised subspecies. Some older classifications, as well as some recent publications,[6] listed the boliviensis population as a separate species. In 2012 the Society for Marine Mammalogy[7] began considering the Bolivian (Inia geoffrensis boliviensis) and Amazonian (Inia geoffrensis geoffrensis) subspecies as full species Inia boliviensis and Inia geoffrensis, respectively; however, much of the scientific community consider the boliviensis population to be a subspecies of Inia geoffrensis. The genus Inia separated from its sister taxon during the Miocene epoch.[8]

The two currently recognized species are:

- I. g. geoffrensis — distributed in the Amazon and Araguaia/Tocantins basins (excluding the Madeira River drainage, upstream of the Teotonio Rapids in Rondônia)

- I. g. humboldtiana — distributed in the Orinoco basin

- I. boliviensis — distributed in the Bolivian sub-basin of the Amazon basin upstream of the Teotonio Rapids in Rondônia

The Amazon river dolphin is closely related to the newly identified Araguaian river dolphin which is believed to have become physically separated and diverged into two separate species. Araguaian Boto have fewer rows of teeth than their closely related Amazon Boto.[9]

Ecology

The Amazon river dolphin is found throughout the Amazon and Orinoco. It is particularly abundant in lowland rivers with extensive floodplains. During the annual rainy season, these rivers flood large areas of forests and marshes along their banks. The Amazon river dolphin specialises in hunting in these habitats, using its unusually flexible neck and spinal cord to maneuver among the underwater tree trunks, and using its long snout to extract prey fish from hiding places in hollow logs and thickets of submerged vegetation.

When the water levels drop, the dolphins move either into the main river channels or into large lakes in the forest, and take advantage of the concentrated prey in these reduced water bodies. They feed on crustaceans, crabs, small turtles, catfish, piranha, shrimp, and other fish.[4]

Behaviour

Adult males have been observed carrying objects in their mouths, objects such as branches or other floating vegetation, balls of hardened clay. The males appear to carry these objects as a socio-sexual display which is part of their mating system. The behaviour is "triggered by an unusually large number of adult males and/or adult females in a group, or perhaps it attracts such animals into the group. A plausible explanation of the results is that object carrying is aimed at females and is stimulated by the number of females in the group, while aggression is aimed at other adult males and is stimulated by object carrying in the group."[10]

The male reaches sexual maturity at about 2 metres (6.6 ft) and the female at about 1.7 metres (5.6 ft). Most calves are born between July and September after a gestation period of 9 to 12 months; they are about 0.81 metres (2.7 ft) long at birth and weigh about 6.8 kilograms (15 lb).[4] The young follow their parents closely for a few months, and often two adults are seen swimming with two or more small juveniles.

Human interaction

The Amazon river dolphin is listed on appendix II[11] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix II as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organized by tailored agreements. In September 2012, Bolivian President Evo Morales enacted a law to protect the dolphin and declared it a national treasure.[12]

In popular culture

In traditional Amazon River folklore, at night, an Amazon river dolphin becomes a handsome young man who seduces girls, impregnates them, and then returns to the river in the morning to become a dolphin again. This dolphin shapeshifter is called an encantado. It has been suggested that the myth arose partly because dolphin genitalia bear a resemblance to those of humans. Others believe the myth served (and still serves) as a way of hiding the incestuous relations which are quite common in some small, isolated communities along the river.[13] In the area, there are tales that it is bad luck to kill a dolphin. Legend also states that if a person makes eye contact with an Amazon river dolphin, he or she will have lifelong nightmares. Local legends also state that the dolphin is the guardian of the Amazonian manatee, and that, should one wish to find a manatee, one must first make peace with the dolphin.

Associated with these legends is the use of various fetishes, such as dried eyeballs and genitalia.[13] These may or may not be accompanied by the intervention of a shaman. A recent study has shown, despite the claim of the seller and the belief of the buyers, none of these fetishes are derived from the boto. They are derived from Sotalia guianensis, are most likely harvested along the coast and the Amazon River delta, and then are traded up the Amazon River. In inland cities far from the coast, many, if not most, of the fetishes are derived from domestic animals such as sheep and pigs.[14]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Template:IUCN2012.2 Database entry includes a lengthy justification of why this species is data-deficient. Cite error: The named reference "iucn" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Animal Info - Boto (Amazon river dolphin)". Animal Info - Endangered Animals. June 7, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ Robin C. Best & Vera M.F. da Silva (1993). "Inia geoffrensis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (426). The American Society of Mammalogists: 1–8.

- ^ a b c American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet. "Boto (Amazon river dolphin)". American Cetacean Society. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ Rice, D. W. (1998). Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution. Society of Marine Mammalogy Special Publication Number 4. p. 231.

- ^ Martínez-Agüero, M., S. Flores-Ramírez, and M. Ruiz-García (2006). "First report of major histocompatibility complex class II loci from the Amazon pink river dolphin (genus Inia)" (PDF). Genetics and Molecular Research. 5 (3): 421–431. PMID 17117356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Committee on Taxonomy. 2012. List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on May 6, 2012.

- ^ Hamilton, H., S. Caballero, A. G. Collins, and R. L. Brownell Jr. (2001). "Evolution of river dolphins". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 268 (1466): 549–556. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1385. PMC 1088639. PMID 11296868.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083623, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0083623instead. - ^ Martin A.R., Da Silva V.M.F. and Rothery P. (2008) "Object carrying as social–sexual display in an aquatic mammal" Animal Behavior, Biology Letters, 4: 1243–2145.

- ^ Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5th March 2009.

- ^ "Bolivia enacts law to protect Amazon pink dolphins". BBC News. 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b M. A. Cravalho (1999). "Shameless creatures: An ethnozoology of the Amazon river dolphin". Ethnology. 38 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2307/3774086.

- ^ Gravena, W., T. Hrbek, V.M.F. da Silva, and I.P. Farias (2008). "Amazon river dolphin love fetishes: From folklore to molecular forensics". Marine Mammal Science. 24: 969–978. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00237.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Omacha Foundation—A non-government and non-profit organization created to study, research and protect river dolphins and other fauna and aquatic ecosystems in Colombia. Winner of the 2007 Whitley Awards (UK).

- Projeto Boto—A non-profit research project that is increasing knowledge, understanding and the conservation prospects of the Amazon's two endemic dolphins—the Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) and the tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis).

- River Dolphin Research Program—Amazon innovative research project totally devoted to the study of the ecology and conservation of river dolphins in the Amazon basin, based in the Federal University of Western Pará (UFOPA). The scope of this research project focuses on ecological studies, as well as the impact that human activities have on their survival.

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Amazon Dolphin

- The Nature Conservancy works to protect habitat for the Amazon river dolphin

- Animal Info page on the Amazon river dolphin

- June 2009 National Geographic story on Amazon river dolphin

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) species profile for River Dolphins

- Amazon river dolphins Being Slaughtered for Bait

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Amazon river dolphin

- Voices in the Sea - Sounds of the Amazon River Dolphin

- Pink dolphins of the Amazon