Axon

An axon (from Greek ἄξων áxōn, axis), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, that typically conducts electrical impulses away from the neuron's cell body. Myelinated axons are known as nerve fibers. The function of the axon is to transmit information to different neurons, muscles and glands. In certain sensory neurons (pseudounipolar neurons), such as those for touch and warmth, the electrical impulse travels along an axon from the periphery to the cell body, and from the cell body to the spinal cord along another branch of the same axon. Axon dysfunction causes many inherited and acquired neurological disorders which can affect both the peripheral and central neurons.

An axon is one of two types of protoplasmic protrusions that extrude from the cell body of a neuron, the other type being dendrites. Axons are distinguished from dendrites by several features, including shape (dendrites often taper while axons usually maintain a constant radius), length (dendrites are restricted to a small region around the cell body while axons can be much longer), and function (dendrites usually receive signals while axons usually transmit them). All of these rules have exceptions, however.

Some types of neurons have no axon and transmit signals from their dendrites. No neuron ever has more than one axon; however in invertebrates such as insects or leeches the axon sometimes consists of several regions that function more or less independently of each other.[1] Most axons branch, in some cases very profusely.

Axons make contact with other cells—usually other neurons but sometimes muscle or gland cells—at junctions called synapses. At a synapse, the membrane of the axon closely adjoins the membrane of the target cell, and special molecular structures serve to transmit electrical or electrochemical signals across the gap. Some synaptic junctions appear partway along an axon as it extends—these are called en passant ("in passing") synapses. Other synapses appear as terminals at the ends of axonal branches. A single axon, with all its branches taken together, can innervate multiple parts of the brain and generate thousands of synaptic terminals.

Anatomy

1. Axon

2. Nucleus of Schwann Cell

3. Schwann Cell

4. Myelin Sheath

5. Neurilemma

Axons are the primary transmission lines of the nervous system, and as bundles they form nerves. Some axons can extend up to one meter or more while others extend as little as one millimeter. The longest axons in the human body are those of the sciatic nerve, which run from the base of the spinal cord to the big toe of each foot. The diameter of axons is also variable. Most individual axons are microscopic in diameter (typically about one micrometer (µm) across). The largest mammalian axons can reach a diameter of up to 20 µm. The squid giant axon, which is specialized to conduct signals very rapidly, is close to 1 millimetre in diameter, the size of a small pencil lead. Axonal arborization (the branching structure at the end of a nerve fiber) also differs from one nerve fiber to the next. Axons in the central nervous system typically show complex trees with many branch points. In comparison, the cerebellar granule cell axon is characterized by a single T-shaped branch node from which two parallel fibers extend. Elaborate arborization allows for the simultaneous transmission of messages to a large number of target neurons within a single region of the brain.

There are two types of axons occurring in the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system: unmyelinated and myelinated axons.[2] Myelin is a layer of a fatty insulating substance, which is formed by two types of glial cells: Schwann cells ensheathing peripheral neurons and oligodendrocytes insulating those of the central nervous system. Along myelinated nerve fibers, gaps in the myelin sheath known as nodes of Ranvier occur at evenly spaced intervals. The myelination enables an especially rapid mode of electrical impulse propagation called saltatory conduction. Demyelination of axons causes the multitude of neurological symptoms found in the disease multiple sclerosis.

If the brain of a vertebrate is extracted and sliced into thin sections, some parts of each section appear dark and other parts lighter in color. The dark parts are known as grey matter and the lighter parts as white matter. White matter gets its light color from the myelin sheaths of axons: the white matter parts of the brain are characterized by a high density of myelinated axons passing through them, and a low density of cell bodies of neurons. The cerebral cortex has a thick layer of grey matter on the surface and a large volume of white matter underneath: what this means is that most of the surface is filled with neuron cell bodies, whereas much of the area underneath is filled with myelinated axons that connect these neurons to each other.[citation needed]

Initial segment

The axon initial segment — the thick, unmyelinated part of an axon that connects directly to the cell body — consists of a specialized complex of proteins. It is approximately 25μm in length and functions as the site of action potential initiation.[3] The density of voltage-gated sodium channels is much higher in the initial segment than in the remainder of the axon or in the adjacent cell body, excepting the axon hillock.[4] The voltage-gated ion channels are known to be found within certain areas of the axonal membrane and initiate action potential, conduction, and synaptic transmission.[2]

Nodes of Ranvier

Nodes of Ranvier (also known as myelin sheath gaps) are short unmyelinated segments of a myelinated axon, which are found periodically interspersed between segments of the myelin sheath. Therefore, at the point of the node of Ranvier, the axon is reduced in diameter.[5] These nodes are areas where action potentials can be generated. In saltatory conduction, electrical currents produced at each node of Ranvier are conducted with little attenuation to the next node in line, where they remain strong enough to generate another action potential. Thus in a myelinated axon, action potentials effectively "jump" from node to node, bypassing the myelinated stretches in between, resulting in a propagation speed much faster than even the fastest unmyelinated axon can sustain.

Action potentials

Most axons carry signals in the form of action potentials, which are discrete electrochemical impulses that travel rapidly along an axon, starting at the cell body and terminating at points where the axon makes synaptic contact with target cells. The defining characteristic of an action potential is that it is "all-or-nothing" — every action potential that an axon generates has essentially the same size and shape. This all-or-nothing characteristic allows action potentials to be transmitted from one end of a long axon to the other without any reduction in size. There are, however, some types of neurons with short axons that carry graded electrochemical signals, of variable amplitude.

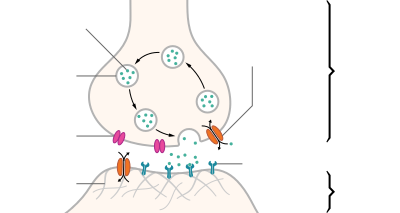

When an action potential reaches a presynaptic terminal, it activates the synaptic transmission process. The first step is rapid opening of calcium ion channels in the membrane of the axon, allowing calcium ions to flow inward across the membrane. The resulting increase in intracellular calcium concentration causes vesicles (tiny containers enclosed by a lipid membrane) filled with a neurotransmitter chemical to fuse with the axon's membrane and empty their contents into the extracellular space. The neurotransmitter is released from the presynaptic nerve through exocytosis. The neurotransmitter chemical then diffuses across to receptors located on the membrane of the target cell. The neurotransmitter binds to these receptors and activates them. Depending on the type of receptors that are activated, the effect on the target cell can be to excite the target cell, inhibit it, or alter its metabolism in some way. This entire sequence of events often takes place in less than a thousandth of a second. Afterward, inside the presynaptic terminal, a new set of vesicles are moved into position next to the membrane, ready to be released when the next action potential arrives. The action potential is the final electrical step in the integration of synaptic messages at the scale of the neuron.[2]

Extracellular recordings of action potential propagation in axons has been demonstrated in freely moving animals. While extracellular somatic action potentials have been used to study cellular activity in freely moving animals such as place cells, axonal activity in both white and gray matter can also be recorded. Extracellular recordings of axon action potential propagation is distinct from somatic action potentials in three ways: 1. The signal has a shorter peak-trough duration (~150μs) than of pyramidal cells (~500μs) or interneurons (~250μs). 2. The voltage change is triphasic. 3. Activity recorded on a tetrode is seen on only one of the four recording wires. In recordings from freely moving rats, axonal signals have been isolated in white matter tracts including the alveus and the corpus callosum as well hippocampal gray matter.[6]

In fact, the generation of action potentials in vivo is sequential in nature, and these sequential spikes constitute the digital codes in the neurons. Although previous studies indicate an axonal origin of a single spike evoked by short-term pulses, physiological signals in vivo trigger the initiation of sequential spikes at the cell bodies of the neurons.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

In addition to propagating action potentials to axonal terminals, the axon is able to amplify the action potentials, which makes sure a secure propagation of sequential action potentials toward the axonal terminal. In terms of molecular mechanisms, voltage-gated sodium channels in the axons possess lower threshold and shorter refractory period in response to short-term pulses.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Development and growth

Development

Studies done on cultured hippocampal neurons suggest that neurons initially produce multiple neurites that are equivalent, yet only one of these neurites is destined to become the axon.[7] It is unclear whether axon specification precedes axon elongation or vice versa,[8] although recent evidence points to the latter. If an axon that is not fully developed is cut, the polarity can change and other neurites can potentially become the axon. This alteration of polarity only occurs when the axon is cut at least 10 μm shorter than the other neurites. After the incision is made, the longest neurite will become the future axon and all the other neurites, including the original axon, will turn into dendrites.[9] Imposing an external force on a neurite, causing it to elongate, will make it become an axon.[10] Nonetheless, axonal development is achieved through a complex interplay between extracellular signaling, intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics.

Extracellular signaling

The extracellular signals that propagate through the extracellular matrix surrounding neurons play a prominent role in axonal development.[11] These signaling molecules include proteins, neurotrophic factors, and extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules. UNC-6 or netrin, a secreted protein, functions in axon formation. When the UNC-6 receptor is mutated, several neurites are irregularly projected out of neurons and finally a single axon is extended anteriorly.[12][13][14][15] The neurotrophic factors nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 3 (NT3) are also involved in axon development and bind to Trk receptors.[16]

The ganglioside-converting enzyme plasma membrane ganglioside sialidase (PMGS), which is involved in the activation of TrkA at the tip of neutrites, is required for the elongation of axons. PMGS asymmetrically distributes to the tip of the neurite that is destined to become the future axon.[17]

Intracellular signaling

During axonal development, the activity of PI3K is increased at the tip of destined axon. Disrupting the activity of PI3K inhibits axonal development. Activation of PI3K results in the production of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PtdIns) which can cause significant elongation of a neurite, converting it into an axon. As such, the overexpression of phosphatases that dephosphorylate PtdIns leads into the failure of polarization.[11]

Cytoskeletal dynamics

The neurite with the lowest actin filament content will become the axon. PGMS concentration and f-actin content are inversely correlated; when PGMS becomes enriched at the tip of a neurite, its f-actin content is substantially decreased.[17] In addition, exposure to actin-depolimerizing drugs and toxin B (which inactivates Rho-signaling) causes the formation of multiple axons. Consequently, the interruption of the actin network in a growth cone will promote its neurite to become the axon.[18]

Growth

Growing axons move through their environment via the growth cone, which is at the tip of the axon. The growth cone has a broad sheet like extension called lamellipodia which contain protrusions called filopodia. The filopodia are the mechanism by which the entire process adheres to surfaces and explores the surrounding environment. Actin plays a major role in the mobility of this system. Environments with high levels of cell adhesion molecules or CAM's create an ideal environment for axonal growth. This seems to provide a "sticky" surface for axons to grow along. Examples of CAM's specific to neural systems include N-CAM, neuroglial CAM or NgCAM, TAG-1, and MAG all of which are part of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Another set of molecules called extracellular matrix adhesion molecules also provide a sticky substrate for axons to grow along. Examples of these molecules include laminin, fibronectin, tenascin, and perlecan. Some of these are surface bound to cells and thus act as short range attractants or repellents. Others are difusible ligands and thus can have long range effects.

Cells called guidepost cells assist in the guidance of neuronal axon growth. These cells are typically other, sometimes immature, neurons.

It has also been discovered through research that if the axons of a neuron were damaged, as long as the soma (the cell body of a neuron) is not damaged, the axons would regenerate and remake the synaptic connections with neurons with the help of guidepost cells. This is also referred to as neuroregeneration.[19]

Nogo-A is a type of neurite growth inhibitory component that is present in the central nervous system myelin membranes (found in an axon). It has a crucial role in restricting axonal regeneration in adult mammalian central nervous system. In recent studies, if Nogo- A is blocked and neutralized, it is possible to induce long-distance axonal regeneration which leads to enhancement of functional recovery in rats and mouse spinal cord. This has yet to be done on humans.[20] A recent study has also found that macrophages activated through a specific inflammatory pathway activated by the Dectin-1 receptor are capable of promoting axon recovery, also however causing neurotoxicity in the neuron.[21]

History

Some of the first intracellular recordings in a nervous system were made in the late 1930s by Kenneth S. Cole and Howard J. Curtis. German anatomist Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters is generally credited with the discovery of the axon by distinguishing it from the dendrites.[2] Swiss Rüdolf Albert von Kölliker and German Robert Remak were the first to identify and characterize the axon initial segment. Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley also employed the squid giant axon (1939) and by 1952 they had obtained a full quantitative description of the ionic basis of the action potential, leading the formulation of the Hodgkin–Huxley model. Hodgkin and Huxley were awarded jointly the Nobel Prize for this work in 1963. The formulas detailing axonal conductance were extended to vertebrates in the Frankenhaeuser–Huxley equations. Louis-Antoine Ranvier was the first to describe the gaps or nodes found on axons and for this contribution these axonal features are now commonly referred to as the Nodes of Ranvier. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish anatomist, proposed that axons were the output components of neurons, describing their functionality.[2] Erlanger and Gasser earlier developed the classification system for peripheral nerve fibers,[22] based on axonal conduction velocity, myelination, fiber size etc. Even recently our understanding of the biochemical basis for action potential propagation has advanced, and now includes many details about individual ion channels.

Injury

In order of degree of severity, injury to a nerve can be described as neurapraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis. Concussion is considered a mild form of diffuse axonal injury.[23] The dysfunction of axons in the nervous system is one of the major causes of many inherited neurological disorders that affect both peripheral and central neurons.[2]

Classification

The axons that make up nerves in the human peripheral nervous system can be classified based on their physical features and signal conduction properties.

Motor

Lower motor neurons have two kind of fibers:

| Type | Erlanger-Gasser Classification |

Diameter (µm) | Myelin | Conduction velocity | Associated muscle fibers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | Aα | 13-20 | Yes | 80–120 m/s | Extrafusal muscle fibers |

| β | Aβ | ||||

| γ | Aγ | 5-8 | Yes | 4–24 m/s[24][25] | Intrafusal muscle fibers |

Sensory

Different sensory receptors are innervated by different types of nerve fibers. Proprioceptors are innervated by type Ia, Ib and II sensory fibers, mechanoreceptors by type II and III sensory fibers and nociceptors and thermoreceptors by type III and IV sensory fibers.

| Type | Erlanger-Gasser Classification |

Diameter (µm) | Myelin | Conduction velocity | Associated sensory receptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | Aα | 13-20 | Yes | 80–120 m/s | Primary receptors of muscle spindle |

| Ib | Aα | 13-20 | Yes | 80–120 m/s | Golgi tendon organ |

| II | Aβ | 6-12 | Yes | 33–75 m/s | Secondary receptors of muscle spindle All cutaneous mechanoreceptors |

| III | Aδ | 1-5 | Thin | 3–30 m/s | Free nerve endings of touch and pressure Nociceptors of neospinothalamic tract Cold thermoreceptors |

| IV | C | 0.2-1.5 | No | 0.5-2.0 m/s | Nociceptors of paleospinothalamic tract Warmth receptors |

Autonomic

The autonomic nervous system has two kinds of peripheral fibers:

| Type | Erlanger-Gasser Classification |

Diameter (µm) | Myelin[26] | Conduction velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| preganglionic fibers | B | 1–5 | Yes | 3–15 m/s |

| postganglionic fibers | C | 0.2–1.5 | No | 0.5–2.0 m/s |

See also

References

- ^ Yau, KW (1976). "Receptive fields, geometry and conduction block of sensory neurons in the CNS of the leech". J. Physiol. 263 (3). Lond: 513–538. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011643. PMC 1307715. PMID 1018277.

- ^ a b c d e f Debanne, Dominique; Campanac, Emilie; Bialowas, Andrzej; Carlier, Edmond; Alcaraz, Gisèle (April 2011). "Axon physiology". Physiological reviews. 91 (2): 555–602. doi:10.1152/physrev.00048.2009. PMID 21527732.

- ^ Clark, BD; Goldberg, EM; Rudy, B (December 2009). "Electrogenic tuning of the axon initial segment". The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry. 15 (6): 651–68. doi:10.1177/1073858409341973. PMC 2951114. PMID 20007821.

- ^ Wollner, DA; Catterall, WA (November 1986). "Localization of sodium channels in axon hillocks and initial segments of retinal ganglion cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (21): 8424–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.21.8424. PMC 386941. PMID 2430289.

- ^ Hess, A; Young, JZ (20 November 1952). "The nodes of Ranvier". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series B. 140 (900): 301–320. doi:10.1098/rspb.1952.0063. JSTOR 82721. PMID 13003931.

- ^ Robbins, A; Fox, S (November 2013). "Short Duration Waveforms Recorded Extracellularly from Freely Moving Rats are Representative of Axonal Activity". Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 7 (181): 7–11. doi:10.3389/fncir.2013.00181. PMC 3831546. PMID 24348338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fletcher, TL; Banker, GA (December 1989). "The establishment of polarity by hippocampal neurons: the relationship between the stage of a cell's development in situ and its subsequent development in culture". Developmental Biology. 136 (2): 446–54. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(89)90269-8. PMID 2583372.

- ^ Jiang, H; Rao, Y (May 2005). "Axon formation: fate versus growth". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (5): 544–6. doi:10.1038/nn0505-544. PMID 15856056.

- ^ Goslin, K; Banker, G (April 1989). "Experimental observations on the development of polarity by hippocampal neurons in culture". The Journal of Cell Biology. 108 (4): 1507–16. doi:10.1083/jcb.108.4.1507. PMC 2115496. PMID 2925793.

- ^ Lamoureux, P; Ruthel, G; Buxbaum, RE; Heidemann, SR (11 November 2002). "Mechanical tension can specify axonal fate in hippocampal neurons". The Journal of Cell Biology. 159 (3): 499–508. doi:10.1083/jcb.200207174. PMC 2173080. PMID 12417580.

- ^ a b Arimura, N; Kaibuchi, K (March 2007). "Neuronal polarity: from extracellular signals to intracellular mechanisms". Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (3): 194–205. doi:10.1038/nrn2056. PMID 17311006.

- ^ Neuroglia and pioneer neurons express UNC-6 to provide global and local netrin cues for guiding migrations in C. elegans

- ^ Serafini, T; Kennedy, TE; Galko, MJ; Mirzayan, C; Jessell, TM; Tessier-Lavigne, M (12 August 1994). "The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6". Cell. 78 (3): 409–24. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90420-0. PMID 8062384.

- ^ Hong, K; Hinck, L; Nishiyama, M; Poo, MM; Tessier-Lavigne, M; Stein, E (25 June 1999). "A ligand-gated association between cytoplasmic domains of UNC5 and DCC family receptors converts netrin-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion". Cell. 97 (7): 927–41. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80804-1. PMID 10399920.

- ^ Hedgecock, EM; Culotti, JG; Hall, DH (January 1990). "The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans". Neuron. 4 (1): 61–85. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-K. PMID 2310575.

- ^ Huang, EJ; Reichardt, LF (2003). "Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 72: 609–42. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. PMID 12676795.

- ^ a b Da Silva, JS; Hasegawa, T; Miyagi, T; Dotti, CG; Abad-Rodriguez, J (May 2005). "Asymmetric membrane ganglioside sialidase activity specifies axonal fate". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (5): 606–15. doi:10.1038/nn1442. PMID 15834419.

- ^ Bradke, F; Dotti, CG (19 March 1999). "The role of local actin instability in axon formation". Science. 283 (5409): 1931–4. doi:10.1126/science.283.5409.1931. PMID 10082468.

- ^ Kunik, D (2011). "Laser-based single-axon transection for high-content axon injury and regeneration studies". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e26832. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026832. PMC 3206876. PMID 22073205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Schwab, Martin E. (2004). "Nogo and axon regeneration". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 14 (1): 118–124. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.004. PMID 15018947.

- ^ Gensel; et al. (2009). "Macrophages promote axon regeneration with concurrent neurotoxicity". Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (12): 3956–3968. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3992-08.2009. PMC 2693768. PMID 19321792.

- ^ Sansom B, "Reflex Isolation" http://www.sansomnia.com

- ^ eMedicine - Traumatic Brain Injury: Definition, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology : Article by Segun T Dawodu, MD, FAAPMR, FAANEM, CIME, DipMI(RCSed)

- ^ Andrew, B. L.; Part, N. J. (1972). "Properties of fast and slow motor units in hind limb and tail muscles of the rat". Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 57 (2): 213–225. PMID 4482075.

- ^ Russell, N. J. (1980). "Axonal conduction velocity changes following muscle tenotomy or deafferentation during development in the rat". J Physiol. 298: 347–360. PMC 1279120. PMID 7359413.

- ^ Pocock, Gillian; et al. (2004). Human Physiology (Second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 187–189. ISBN 0-19-858527-6.

External links

- Histology image: 3_09 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "Slide 3 Spinal cord"

- - Bialowas, Andrzej, Carlier, Edmond, Campanac, Emilie, Debanne, Dominique, Alcaraz. Axon Physiology, GisèlePHYSIOLOGICAL REVIEWS, V. 91 (2), 04/2011, p. 555-602.