Ayutthaya Kingdom

Kingdom of Ayutthaya อาณาจักรอยุธยา | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1351–1767 | |||||||||||

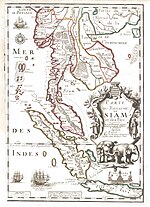

1400 CE Blue Violet: Ayutthaya Kingdom Teal: Lan Xang Purple: Lanna Orange: Sukhothai Kingdom Red: Khmer Empire Yellow: Champa Blue: Dai Viet | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ayutthaya | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Thai | ||||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism, Hinduism, Roman Catholicism, Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1351–69 | Ramathibodi I | ||||||||||

• 1590–1605 | Naresuan | ||||||||||

• 1656–88 | Narai | ||||||||||

• 1758–67 | Boromaracha V | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Chatu Sabombh | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages & Renaissance | ||||||||||

• King Ramathibodi I ascends the throne in Ayutthaya | 1351 | ||||||||||

• Personal union with Sukhothai kingdom | 1468 | ||||||||||

• Burmese vassal | 1564, 1569 | ||||||||||

• Independence from Burmese | 1584 | ||||||||||

• End of Sukhothai Dynasty | 1629 | ||||||||||

| 1767 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

Ayutthaya (Thai: อาณาจักรอยุธยา, RTGS: Anachak Ayutthaya, also Ayudhya, [ʔaːnaːtɕ͡àk ʔajúttʰajaː]) was a Siamese kingdom that existed from 1351 to 1767. Ayutthaya was friendly towards foreign traders, including the Chinese, Vietnamese (Annamese), Indians, Japanese and Persians, and later the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and French, permitting them to set up villages outside the city walls. In the sixteenth century, it was described by foreign traders as one of the biggest and wealthiest cities in the East. The court of King Narai (1656–88) had strong links with that of King Louis XIV of France, whose ambassadors compared the city in size and wealth to Paris.

By 1550, the kingdom's vassals included some city-states in the Malay Peninsula, Lan Xiang (Laos), Sukhothai, Chiang Mai (Lanna), Cambodia and the Shan States.[1]

According to foreign accounts, Ayutthaya was officially known as Siam, but many sources also say that the people of Ayutthaya called themselves Tai, and their kingdom Krung Tai or 'the Kingdom of the Tais'.

Historical overview

Origins

According to the most widely accepted version of its origin, the Siamese state based at Ayutthaya in the valley of the Chao Phraya River rose from the earlier, nearby kingdoms of Lavo (at that time still under the Khmer control) and Suphannaphoom (Suvarnabhumi). One source says that, in the mid-fourteenth century, due to the threat of an epidemic, King U Thong moved his court south into the rich floodplain of the Chao Phraya on an island surrounded by rivers, which was the former seaport city of Ayothaya, or Ayothaya Si Raam Thep Nakhon, the Angelic City of Sri Rama. The new city was known as Ayothaya, or Krung Thep Dvaravadi Si Ayothaya. Later it became widely known as Ayutthaya, the Invincible City.[2]

Other sources say that King Uthong was a rich merchant of Chinese origin from Phetchaburi, a coastal city in the south, who moved to seek fortune in Ayothaya city. The name of the city indicates the influence of Hinduism in the region. It is believed that this city is associated with the Thai national epic Ramakien, which is a southeastern version of Hindu epic Ramayana.

Conquests and expansion

By the end of the century, Ayutthaya was regarded as the strongest power in mainland Southeast Asia. Ayutthaya began its hegemony by conquering northern kingdoms and city-states like Sukhothai, Kamphaeng Phet and Phitsanuloke. Before the end of the fifteenth century, Ayutthaya launched attacks on Angkor, the classical great power of the region. Angkor's influence eventually faded from the Chao Phraya River Plain while Ayutthaya became a new great power.

However, the kingdom of Ayutthaya was not a unified state but rather a patchwork of self-governing principalities and tributary provinces owing allegiance to the king of Ayutthaya under The Circle of Power, or the mandala system, as some scholars suggested .[3] These principalities might be ruled by members of the royal family of Ayutthaya, or by local rulers who had their own independent armies, having a duty to assist the capital when war or invasion occurred. However, it was evident that from time to time local revolts, led by local princes or kings, took place. Ayutthaya had to suppress them.

Due to the lack of succession law and a strong concept of meritocracy, whenever the succession was in dispute, princely governors or powerful dignitaries claiming their merit gathered their forces and moved on the capital to press their claims, culminating in several bloody coups.[4]

From the fifteenth century, Ayutthaya showed an interest in the Malay Peninsula, where the great trading port of Malacca contested its claims to sovereignty. Ayutthaya launched several abortive conquests on Malacca. Due to the military support of Ming China, Malacca was diplomatically and economically fortified. In the early fifteenth century the Ming Admiral Zheng He had established one of his bases of operation in the port city, so the Chinese could not afford to lose such a strategic position to the Siamese. Under this protection, Malacca flourished into one of Ayutthaya's great foes, until its conquest in 1511 by the Portuguese.[5]

Starting in the middle of 16th century, the kingdom came under repeated attacks by the Toungoo Dynasty of Burma. The Burmese began the hostilities with an invasion in 1548 but failed. The second Burmese invasion led by King Bayinnaung forced King Maha Chakkraphat to surrender in April 1564. The royal family was taken to Pegu, with the king's eldest son Mahinthrathirat installed as the vassal king.[6][7] In 1568, Mahinthrathirat revolted when his father managed to return back from Pegu as a monk. The ensuing third invasion captured Ayutthaya in 1569, and Bayinnaung made Maha Thammarachathirat vassal king.[7] Siamese nobles, including one Prince Naresuan, were brought to Pegu.

After Bayinnaung's death in 1581, Maha Thammarachathirat proclaimed Ayutthaya's independence in 1584. The Siamese fought off repeated Burmese invasions, capped by an elephant duel between King Naresuan and Burmese heir-apparent Mingyi Swa in 1593 in which Naresuan famously slew Mingyi Swa (observed 18 January as Royal Thai Armed Forces day.) Naresuan went on capture the entire Tenasserim coast (up to Martaban) and Lan Na from the Burmese. Northern Tenasserim and Lan Na fell back to Burmese control after Naresuan's death but after 1615, Burmese invasions stopped.[8] The kingdom attempted to take over Lan Na and northern Tenasserim in 1662 but failed.[9]

Foreign trade brought Ayutthaya not only luxury items but also new arms and weapons. In the mid-seventeenth century, during King Narai's reign, Ayutthaya became very prosperous.[10] In the eighteenth century, Ayutthaya gradually lost control over its provinces. Provincial governors exerted their power independently, and rebellions against the capital began.

In the mid-eighteenth century, Ayutthaya again became ensnared in wars with the Burmese. The first invasion by the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma failed. The second invasion succeeded in sacking the Ayutthaya city and ending the kingdom in April 1767.

Kingship of Ayutthaya Kingdom

The kings of Ayutthaya were absolute monarchs with semi-religious status. Their authority derived from the ideologies of Hinduism and Buddhism as well as from natural leadership. The king of Sukhothai was the moral inspiration of the Inscription Number 1 found in Sukhothai, which stated that King Ramkhamhaeng would hear the petition of any subject who rang the bell at the palace gate. The king was thus considered as a father by his people.

At Ayutthaya, however, the paternal aspects of kingship disappeared. The king was considered chakkraphat, the Sanskrit-Pali term for the Chakravartin who through his adherence to the law made all the world revolve around him.[11] According to Hindu tradition, the king is the Avatar of God Vishnu, the Destroyer of Demons, who was born to be the defender of the people. The Buddhist belief in the king is as the Righteous ruler or Dhammaraja, aiming at the well-being of the people, who strictly follows the teaching of the Buddha.

The kings' official names were reflections of those religions: Hinduism and Buddhism. They were considered as the incarnation of various Hindu gods: Indra, Shiva or Vishnu (Rama). The coronation ceremony was directed by Brahmins as the Hindu god Shiva was "lord of the universe". However, according to the codes, the king had the ultimate duty as protector of the people and the annihilator of evil.

On the other hand, according to Buddhism's influence in place of Hinduism, the king was also believed to be a Bodhisattva or Buddha-like. He followed and respected the Dhamma of the Buddha. One of the most important duties of the king was to build a temple or a Buddha statue as a symbol of prosperity and peace.[11]

For locals, another aspect of the kingship was also the analogy of "The Lord of the Land", (Phra Chao Phaendin), or He who Rules the Earth. According to the court etiquette, a special language, Rachasap (Sanskrit: Rājāśabda, Royal Language), was used to communicate with or about royalty. In Ayutthaya, the king was said to grant land to his subjects, from nobles to commoners, even monks and beggars, according to the rule of Sakna or Sakdina. However, there is no concrete evidence of Ayutthaya's land management system. The Sakna or Sakdina system is not quite the same as feudalism in Europe.[12]

The French Abbé de Choisy, who came to Ayutthaya in 1685, wrote that, "the king has absolute power. He is truly the god of the Siamese: no-one dares to utter his name." Another 17th-century writer, the Dutchman Van Vliet, remarked that the King of Siam was "honoured and worshipped by his subjects second to god." Laws and orders were issued by the king. For sometimes the king himself was also the highest judge who judged and punished important criminals such as traitors or rebels.[13]

One of the numerous institutional innovations of King Trailokanat (1448–88) was to adopt the position of uparaja, translated as "viceroy" or "prince", usually held by the king's senior son or full brother, in an attempt to regularize the succession to the throne—a particularly difficult feat for a polygamous dynasty. In practice, there was inherent conflict between king and uparaja and frequent disputed successions.[14] However, it is evident that the power of the Throne of Ayutthaya had its limit. The hegemony of the Ayutthaya king was always based on his charisma in terms of his age and supporters. Without supporters, bloody coups took place from time to time. The most powerful figures of the capital were always generals, or the Minister of Military Department, Kalahom. During the last century of Ayutthaya, the bloody fighting among princes and generals, aiming at the throne, plagued the court.

Social and political development

The reforms of King Trailok (r.1448-1488) placed the king of Ayutthaya at the centre of a highly stratified social and political hierarchy that extended throughout the realm. Despite a lack of evidence, it is believed that in the Ayutthaya Kingdom, the basic unit of social organization was the village community composed of extended family households. Title to land resided with the headman, who held it in the name of the community, although peasant proprietors enjoyed the use of land as long as they cultivated it.[15] The lords gradually became courtiers (อำมาตย์) and tributary rulers of minor cities. The king ultimately came to be recognized as the earthly incarnation of Shiva or Vishnu, and became the sacred object of politico-religious cult practices officiated over by royal court Brahmans, part of the Buddhist court retinue. In the Buddhist context, the devaraja (divine king) was a bodhisattva (an enlightened being who, out of compassion, forgoes nirvana in order to aid others). The belief in divine kingship prevailed into the eighteenth century, although by that time its religious implications had limited impact.

With ample reserves of land available for cultivation, the realm depended on the acquisition and control of adequate manpower for farm labor and defense. The dramatic rise of Ayutthaya had entailed constant warfare and, as none of the parties in the region possessed a technological advantage, the outcome of battles was usually determined by the size of the armies. After each victorious campaign, Ayutthaya carried away a number of conquered people to its own territory, where they were assimilated and added to the labor force.[15] Ramathibodi II (r.1491–1529) established the Siamese Corvée system, under which every freeman had to be registered as a servant (phrai) with the local lords, Chao Nai (เจ้านาย). When war broke out, male phrai were subject to impressment. Above the phrai was a nai, who was responsible for military service, corvée labor on public works, and on the land of the official to whom he was assigned. Phrai Suay (ไพร่ส่วย) met labor obligations by paying a tax. If he found the forced labor under his nai repugnant, he could sell himself as a slave (ทาส) to a more attractive nai or lord, who then paid a fee in compensation for the loss of corvée labor. As much as one-third of the manpower supply into the nineteenth century was composed of phrai.[15]

Wealth, status, and political influence were interrelated. The king allotted rice fields to court officials, provincial governors, military commanders, in payment for their services to the crown, according to the sakdi na system. The size of each official's allotment was determined by the number of commoners or phrai he could command to work it. The amount of manpower a particular headman, or official, could command determined his status relative to others in the hierarchy and his wealth. At the apex of the hierarchy, the king, who was symbolically the realm's largest landholder, theoretically commanded the services of the largest number of phrai, called phrai luang (royal servants), who paid taxes, served in the royal army, and worked on the crown lands.[15]

However, the recruitment of the armed forces depended on nai, or mun nai, literally meaning 'lord', officials who commanded their own phrai som, or subjects. These officials had to submit to the king's command when war broke out. Officials thus became the key figures to the kingdom's politics. At least two officials staged coups, taking the throne themselves while bloody struggles between the king and his officials, followed by purges of court officials, were always seen.[15]

King Trailok, in the early sixteenth century, established definite allotments of land and phrai for the royal officials at each rung in the hierarchy, thus determining the country's social structure until the introduction of salaries for government officials in the nineteenth century.[15]

Outside this system to some extent were the Buddhist monkhood, or sangha, which all classes of Siamese men could join, and the Chinese. Buddhist monasteries (wats) became the centres of Siamese education and culture, while during this period the Chinese first began to settle in Siam, and soon began to establish control over the country's economic life: another long-standing social problem.[15]

The Chinese were not obliged to register for corvée duty, so they were free to move about the kingdom at will and engage in commerce. By the sixteenth century, the Chinese controlled Ayutthaya's internal trade and had found important places in the civil and military service. Most of these men took Thai wives because few women left China to accompany the men.[15]

Ramathibodi I was responsible for the compilation of the Dharmashastra, a legal code based on Hindu sources and traditional Thai custom. The Dharmashastra remained a tool of Thai law until late in the 19th century. A bureaucracy based on a hierarchy of ranked and titled officials was introduced, and society was organised in a related manner. Yet the Hindu caste system was not adopted.[16]

The sixteenth century witnessed the rise of Burma which, under an aggressive dynasty, had overrun Chiang Mai and Laos and made war on the Thai. In 1569 Burmese forces joined by Thai rebels, mostly royal family members of Siam, captured the city of Ayutthaya and carried off the whole royal family to Burma. Dhammaraja (1569–90), a Thai governor who had aided the Burmese, was installed as vassal king at Ayutthaya. Thai independence was restored by his son, King Naresuan (1590–1605), who turned on the Burmese and by 1600 had driven them from the country.[17]

Determined to prevent another treason like his father's, Naresuan set about unifying the country's administration directly under the royal court at Ayutthaya. He ended the practice of nominating royal princes to govern Ayutthaya's provinces, assigning instead court officials who were expected to execute policies handed down by the king. Thereafter royal princes were confined to the capital. Their power struggles continued, but at court under the king's watchful eye.[18]

In order to ensure his control over the new class of governors, Naresuan decreed that all freemen subject to phrai service had become phrai luang, bound directly to the king, who distributed the use of their services to his officials. This measure gave the king a theoretical monopoly on all manpower, and the idea developed that since the king owned the services of all the people, he also possessed all the land. Ministerial offices and governorships—-and the sakdina that went with them—-were usually inherited positions dominated by a few families often connected to the king by marriage. Indeed, marriage was frequently used by Thai kings to cement alliances between themselves and powerful families, a custom prevailing through the nineteenth century. As a result of this policy, the king's wives usually numbered in the dozens.[18]

Even with Naresuan's reforms, the effectiveness of the royal government over the next 150 years was unstable. Royal power outside the crown lands-—although in theory absolute—was in practice limited by the looseness of the civil administration. The influence of central government and the king was not extensive beyond the capital. When war with the Burmese broke out in late eighteenth century, provinces easily abandoned the capital. As the enforcing troops were not easily rallied to defend the capital, the City of Ayutthaya could not stand against the Burmese aggressors.[18]

Religion

Ayutthaya's main religion was Theravada Buddhism. Many areas of the kingdom also practiced Mahayana Buddhism and, influenced by French Missionaries who arrived through China in the 17th century, some small areas converted to Catholicism.[19]

Economic development

The Thais never lacked a rich food supply. Peasants planted rice for their own consumption and to pay taxes. Whatever remained was used to support religious institutions. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, however, a remarkable transformation took place in Thai rice cultivation. In the highlands, where rainfall had to be supplemented by a system of irrigation that controlled the water level in flooded paddies, the Thais sowed the glutinous rice that is still the staple in the geographical regions of the North and Northeast. But in the floodplain of the Chao Phraya, farmers turned to a different variety of rice—-the so-called floating rice, a slender, non-glutinous grain introduced from Bengal—-that would grow fast enough to keep pace with the rise of the water level in the lowland fields.[20]

The new strain grew easily and abundantly, producing a surplus that could be sold cheaply abroad. Ayutthaya, situated at the southern extremity of the floodplain, thus became the hub of economic activity. Under royal patronage, corvée labor dug canals on which rice was brought from the fields to the king's ships for export to China. In the process, the Chao Phraya Delta—-mud flats between the sea and firm land hitherto considered unsuitable for habitation—-was reclaimed and placed under cultivation. Traditionally the king had a duty to perform a religious ceremony blessing the rice plantation.[20]

Although rice was abundant in Ayutthaya, rice export was banned from time to time when famine occurred because of natural calamity or war. Rice was usually bartered for luxury goods and armaments from westerners, but rice cultivation was mainly for the domestic market and rice export was evidently unreliable. Trade with Europeans was lively in the seventeenth century. In fact European merchants traded their goods, mainly modern arms such as rifles and cannons, with local products from the inland jungle such as sapan woods, deerskin and rice. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese voyager, mentioned in the sixteenth century that Ayutthaya, or Odia, was rich in good merchandise. Most of the foreign merchants coming to Ayutthaya were European and Chinese, and were taxed by the authorities. The kingdom had an abundance of rice, salt, dried fish, arrack and vegetables.[21]

Trade with foreigners, mainly the Dutch, reached its peak in the seventeenth century. Ayutthaya became a main destination for merchants from China and Japan. It was apparent that foreigners began taking part in the kingdom's politics. Ayutthayan kings employed foreign mercenaries who sometimes entered the wars with the kingdom's enemies. However, after the purge of the French in late seventeenth century, the major traders with Ayutthaya were the Chinese. The Dutch from the Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC), were still active. Ayutthaya's economy declined rapidly in the eighteenth century, until the Burmese invasion caused the total collapse of Ayutthaya's economy in 1788.[22]

Contacts with the West

In 1511, immediately after having conquered Malacca, the Portuguese sent a diplomatic mission headed by Duarte Fernandes to the court of King Ramathibodi II of Ayutthaya. Having established amicable relations between the kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of Siam, they returned with a Siamese envoy with gifts and letters to the King of Portugal.[23] They were probably the first Europeans to visit the country. Five years after that initial contact, Ayutthaya and Portugal concluded a treaty granting the Portuguese permission to trade in the kingdom. A similar treaty in 1592 gave the Dutch a privileged position in the rice trade.

Foreigners were cordially welcomed at the court of Narai (1657–1688), a ruler with a cosmopolitan outlook who was nonetheless wary of outside influence. Important commercial ties were forged with Japan. Dutch and English trading companies were allowed to establish factories, and Thai diplomatic missions were sent to Paris and The Hague. By maintaining all these ties, the Thai court skillfully played off the Dutch against the English and the French, avoiding the excessive influence of a single power.[24]

In 1664, however, the Dutch used force to exact a treaty granting them extraterritorial rights as well as freer access to trade. At the urging of his foreign minister, the Greek adventurer Constantine Phaulkon, Narai turned to France for assistance. French engineers constructed fortifications for the Thais and built a new palace at Lopburi for Narai. In addition, French missionaries engaged in education and medicine and brought the first printing press into the country. Louis XIV's personal interest was aroused by reports from missionaries suggesting that Narai might be converted to Christianity.[25]

The French presence encouraged by Phaulkon, however, stirred the resentment and suspicions of the Thai nobles and Buddhist clergy. When word spread that Narai was dying, a general, Phetracha, killed the designated heir, a Christian, and had Phaulkon put to death along with a number of missionaries. The arrival of English warships provoked a massacre of more Europeans. Phetracha (reigned 1688–93) seized the throne and expelled the remaining foreigners. Some studies said that Ayutthaya began a period of alienation from western traders, while welcoming more Chinese merchants. But other recent studies argue that, due to wars and conflicts in Europe in the mid-eighteenth century, European merchants reduced their activities in the East. However, it was apparent that the Dutch East Indies Company or VOC was still doing business in Ayutthaya despite political difficulties.[25]

The final phase

After a bloody period of dynastic struggle, Ayutthaya entered into what has been called the golden age, a relatively peaceful episode in the second quarter of the eighteenth century when art, literature, and learning flourished. There were foreign wars. Ayutthaya fought with the Nguyễn Lords (Vietnamese rulers of South Vietnam) for control of Cambodia starting around 1715. But a greater threat came from Burma, where the new Alaungpaya dynasty had subdued the Shan states.[26]

The last fifty years of the kingdom witnessed a bloody struggle among the princes. The throne was their prime target. Purges of court officials and able generals followed. The last monarch, Ekathat, originally known as Prince Anurakmontree, forced the king, who was his younger brother, to step down and took the throne himself.[27]

According to a French source, Ayutthaya in the eighteenth century comprised these principal cities: Martaban, Ligor or Nakhon Sri Thammarat, Tenasserim, Jungceylon or Phuket Island, Singora or Songkhla. Her tributaries were Patani, Pahang, Perak, Kedah and Malacca.[28]

In 1765, a combined 40,000-strong force of Burmese armies invaded the territories of Ayutthaya from the north and west.[29] Major outlying towns quickly capitulated. The only notable example of successful resistance to these forces was found at the village of Bang Rajan. After a 14 months' siege, the city of Ayutthaya capitulated and was burned in April 1767.[30] Ayutthaya's art treasures, the libraries containing its literature, and the archives housing its historic records were almost totally destroyed,[30] and the Burmese brought the Ayutthaya Kingdom to ruin.[30]

The Burmese rule lasted a mere few months. The Burmese, who had also been fighting a simultaneous war with the Chinese since 1765, were forced to withdraw in early 1768 when the Chinese forces threatened their own capital. It is quite likely that had Ayutthaya not fallen in April, it would have never fallen at all since the Burmese siege would have to be abandoned.[31]

With most Burmese forces having withdrawn, the country was reduced to chaos. Provinces proclaimed independence under generals, rogue monks, and members of the royal family. One general, Phraya Taksin, former governor of Taak, began the reunification effort.[32][33]

All that remains of the old city are some impressive ruins of the royal palace. General Taak-Sin, the governor of Taak, who fled the capital, gathering forces, began striking back at the Burmese. He finally established a capital at Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya from the present capital, Bangkok. Taak-Sin ascended the throne, becoming known as King Taak-Sin or Taksin.[32][33]

The ruins of the historic city of Ayutthaya and "associated historic towns" in the Ayutthaya historical park have been listed by the UNESCO as World Heritage Site.[34] The city of Ayutthaya was refounded near the old city, and is now capital of the Ayutthaya province.[35]

Kings of Ayutthaya

1st Uthong Dynasty (1350–1370)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Chao Uthong (Somdet Phra Ramathibodi I) |

1314 | 1350 | 1369 (20 years) | • First King of Ayutthaya | |

| Somdet Phra Ramesuan (First Reign) | 1339 | 1369 | 1370 (less than one year — abdicated) | 1395 | • Son of Uthong |

1st Suphannaphum Dynasty (1370–1388)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Borommarachathirat I (Khun Luang Pha Ngua) |

? | 1370 | 1388 (18 years) | • Usurper • Former Lord of Suphanburi | |

| Somdet Phra Chao Thong Lan (Chao Thong Chan) |

? | 1388 (7 days — usurped) | • Son of Borommarachathirat I | ||

2nd Uthong Dynasty (1388–1409)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Ramesuan (Second Reign) | 1339 | 1388 | 1395 (7 years) | • Former King reclaiming the throne • Son of Uthong | |

| Somdet Phra Rama Ratchathirat | 1356 | 1395 | 1409 (14 years — usurped) | ? | • Son of Ramesuan |

2nd Suphannaphum Dynasty (1409–1569)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Intha Racha (Phra Chao Nakhon Int) |

1359 | 1409 | 1424 (15 years) | • Grandson of Borommarachathirat I • Former Lord of Suphanburi, offered crown | |

| Somdet Phra Borommarachathirat II (Chao Sam Phraya) |

? | 1424 | 1448 (24 years) | • Son of Intha Racha | |

| Somdet Phra Boromma Trailokanat | 1431 | 1448 | 1488 (40 years) | • Son of Borommarachathirat II | |

| Somdet Phra Borommarachathirat III | ? | 1488 | 1491 (3 years) | • Son of Trailokanat | |

| Somdet Phra Ramathibodi II (Phra Chettathiraj) |

1473 | 1491 | 1529 (38 years) | • Younger brother of Borommarachathirat III • Son of Trailokanat | |

| Somdet Phra Borommarachathirat IV (Somdet Phra Borommaracha Nor Buddhankoon) (Phra Athitawongse) |

? | 1529 | 1533 (4 years) | • Son of Ramathibodi II | |

| Phra Ratsadathirat | 1529 | 1533 (4 months) (usurped) |

• Son of Borommarachathirat IV • Child King, reign under regency | ||

| Somdet Phra Chairacha (Somdet Phra Chairacha Thirat) |

? | 1533 | 1546 (13 years) | • Uncle of Ratsadathirat • Son of Ramathibodi II • Usurper | |

| Phra Yodfa (Phra Keowfa) |

1535 | 1546 | 1548 (2 years) | • Son of Chairacha | |

| Khun Worawongsathirat (Khun Chinnarat) (Bun Si) |

? | 1548 (42 days) (Removed) |

• Usurper monarch, not accepted by some historians | ||

| Somdet Phra Maha Chakkraphat (Phra Chao Chang Pueak) |

1509 | 1548 | 1564 (16 years) | • Son of Ramathibodi II • Younger brother of Borommarachathirat IV and Chairacha • Seized the throne from usurper • Became a monk at Pegu (1564–1568) | |

| Vassal of Burma (1564–1568) | |||||

| Somdet Phra Mahinthrathirat | 1539 | 1564 | 1569 (4 years as vassal king, 1 year as king) |

• Son of Maha Chakkrapat and Queen Suriyothai | |

| Vassal of Burma (1569–1584) | |||||

Sukhothai Dynasty (1569–1629)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Maha Thammarachathirat (Somdet Phra Sanphet I) |

1517 | 1569 | 29 July 1590 (21 years) | • Former Lord of Sukhothai • Installed as vassal of Bayinnaung of Burma, declared independence in 1584 | |

| Somdet Phra Naresuan the Great (Somdet Phra Sanphet II) |

25 April 1555 | 29 July 1590 | 7 April 1605 (15 years) | • Son of Maha Thammarachathirat | |

| Somdet Phra Ekathotsarot (Somdet Phra Sanphet III) |

1557 | 25 April 1605 | 1620 (15 years) | • Son of Maha Thammarachathirat | |

| Somdet Phra Si Saowaphak (Somdet Phra Sanphet IV) |

? | 1620 (less than a year) | • Son of Ekathotsarot | ||

| Somdet Phra Songtham (Somdet Phra Borommaracha I) |

? | 1620 | 12 December 1628 (8 years) | • Minor relative, natural son of Ekathotsarot; invited to take the throne after leaving the Sangha | |

| Somdet Phra Chetthathirat (Somdet Phra Borommaracha II) |

circa 1613 | 1628 | 1629 (1 year) (assassinated) |

• Son of Songtham | |

| Phra Athittayawong | 1618 | 1629 (36 days — usurped) | • Younger brother of Chetthathirat • Son of Songtham | ||

Prasat Thong Dynasty (1630–1688)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Chao Prasat Thong (Somdet Phra Sanphet V) |

1599 | 1629 | 1656 (27 years) | • Usurper, formerly the Kalahom • Rumored to be a son of Ekathotsarot | |

| Somdet Chao Fa Chai (Somdet Phra Sanphet VI) |

? | 1656 (9 months) (usurped) |

• Son of Prasat Thong | ||

| Somdet Phra Si Suthammaracha (Somdet Phra Sanphet VII) |

? | 1656 (2 months 17 days — usurped) | 26 August 1656 (executed) |

• Usurper, Uncle of Chao Fa Chai • Younger brother of Prasat Thong | |

| Somdet Phra Narai the Great (Somdet Phra Ramathibodi III) |

1629 | 26 August 1656 | 11 July 1688 (32 years) | • Usurper, nephew of Si Suthammaracha • Son of Prasat Thong • Half-brother of Chao Fa Chai | |

Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty (1688–1767)

| Name | Birth | Reign From | Reign Until | Death | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somdet Phra Phetracha | 1632 | 1688 | 1703 (15 years) | • Usurper, cousin of Narai • Former commander of the Royal Elephant Corps | |

| Somdet Phra Suriyenthrathibodi (Somdet Phra Sanphet VIII) (Phra Chao Suea) |

? | 1703 | 1708 (5 years) | • Son of Narai | |

| Somdet Phra Chao Yu Hua Thai Sa (Somdet Phra Sanphet IX) |

? | 1708 | 1732 (24 years) | • Son of Suriyenthrathibodi | |

| Somdet Phra Chao Yu Hua Boromakot | ? | 1732 | 1758 (26 years) | • Brother of Thai Sa, Former Front Palace • Son of Suriyenthrathibodi | |

| Somdet Phra Chao Uthumphon (Somdet Phra Ramathibodi IV) (Khun Luang Hawat) |

? | 1758 (2 months — usurped) | 1796 | • Son of Boromakot | |

| Somdet Phra Chao Ekkathat (Somdet Phra Chao Yu Hua Phra Thinang Suriyat Amarin) |

? | 1758 | 7 April 1767 (9 years — removed) | 17 April 1767 | • Brother of Uthumphon • Usurper, Former Front Palace • Son of Boromakot |

| End of Ayutthaya | |||||

List of notable foreigners in seventeenth century Ayutthaya

- Constantine Phaulkon, Greek Adventurer and First Councillor of King Narai

- François-Timoléon de Choisy

- Father Guy Tachard, French Jesuit Writer and Siamese Ambassador to France (1688)

- Louis Laneau, Apostolic Vicar of Siam

- Yamada Nagamasa, Japanese adventurer who became the ruler of the Nakhon Si Thammarat province

Image Gallery

-

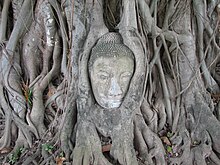

Detached Buddha head encased in fig tree roots

-

Seated Buddha , Ayutthaya

-

Seated Buddha, Ayutthaya

See also

Notes

- ^ Hooker, Virginia Matheson (2003). A Short History of Malaysia: Linking East and West. St Leonards, New South Wales, AU: Allen & Unwin. p. 72. ISBN 1864489553. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ^ "The Tai Kingdom of Ayutthaya". The Nation: Thailand's World. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ Higham 1989, p. 355

- ^ "The Aytthaya Era, 1350-1767". U. S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Jin, Shaoqing (2005). Office of the People's Goverernment of Fujian Province (ed.). Zheng He's voyages down the western seas. Fujian, China: China Intercontinental Press. p. 58. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. Phayre (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta. p. 111.

- ^ a b GE Harvey (1925). History of Burma. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. pp. 167–170.

- ^ Phayre, pp. 127-130

- ^ Phayre, p. 139

- ^ Wyatt 2003, pp. 90–121

- ^ a b "Introduction". South East Asia site. Northern Illinois University. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ "The National Language". Mahidol University. November 1, 2002. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ Bavadam, Lyla (March 14, 2006). "Magnificint Ruins". Frontline. 26 (6). Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ "HM Second King Pinklao". Soravij. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Ayutthaya". Mahidol University. November 1, 2002. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ "Background Note: Thailand". U.S. Department of State. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ross, Ph.D., Kelly L. (2008). "The Periphery of China -- Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Burma, Tibet, and Mongolia". Freisian School. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ a b c Ring, Trudy (1995). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Vol. 5. Sharon La Boda. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 18844964044. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Indobhasa, Sao (2009). "Buddhism in Ayutthaya (1351-1767)". Ceylon Journey. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ a b "The Economy and Economic Changes". The Ayutthaya Administration. Department of Provincial Administration. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ Tome Pires. The Suma Oriental of Tome Pires. London, The Hakluyt Society,1944, p.107

- ^ Vandenberg, Tricky (March 2009). "The Dutch in Ayutthaya". History of Ayutthaya. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ Donald Frederick Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley, "Asia in the making of Europe", pp. 520-521, University of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-226-46731-3

- ^ "The Beginning of Relations with Buropean Nations and Japan (sic)". Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2006. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ a b Smithies, Michael (2002). Three military accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam. Bangkok: Orchid Press. pp. 12, 100, 183. ISBN 9745240052.

- ^ "Ayutthaya". Thailand by Train. 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Ruangsilp 2007, p. 203

- ^ Dictionaire geographique universel. Amsterdam & Utrecht: Chez Francois Halma, 1750. p.880.

- ^ Harvey, p. 250

- ^ a b c Ruangsilp 2007, p. 218

- ^ Harvey, p. 253

- ^ a b Syamananda 1990, p. 94

- ^ a b Wood 1924, pp. 254–264

- ^ "World Heritagae Site Ayutthaya". UNESCO. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ "พระราชกฤษฎีกาเปลี่ยนชื่ออำเภอกรุงเก่า พ.ศ. ๒๕๐๐" (PDF). Royal Gazette (in Thai). 74 (25 ก): 546. March 5, 1957.

References

- Original text adapted from the Library of Congress Country Study of Thailand

- Higham, Charles (1989). The Archaeology of Mainland Southeast Asia. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521275523. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marcinkowski, M. Ismail (2005). From Isfahan to Ayutthaya: Contacts between Iran and Siam in the 17th Century. Singapore: Pustaka Nasional. ISBN 9971774917. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Ruangsilp, Bhawan (2007). Dutch East India Company merchants at the court of Ayutthaya: Dutch Perceptions of the Thai Kingdom c. 1604-1765. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 0300084757. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Syamananda, Rong (1990). A History of Thailand. Chulalongkorn University. ISBN 9740764134.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wood, W.A.R (1924). A History of Siam. London: Fisher Unwin Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand: A Short History. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300084757.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Smithies, Michael. A Siamese Embassy Lost in Africa 1686: The Odyssey of Ok-Khun Chamman. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1999.

Dissertations retrieved from ProQuest-Dissertations and Theses on Aug.16,2006

Subject: Art History

- Listopad, John A. "The art and architecture of the reign of Somdet Phra Narai." Diss. U of Michigan, 1995.

Subject: Buddhist literature

- Chrystall, Beatrice. "Connections without limit: The refiguring of the Buddha in the Jinamahanidana." Diss. Harvard U, 2004.

Subject: History

- Smith, George V. "The Dutch East India Company in the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, 1604-1694." Diss. Northern Illinois U, 1974.

Subject: Buddhist literature

- Chrystall, Beatrice. "Connections without limit: The refiguring of the Buddha in the Jinamahanidana." Diss. Harvard U, 2004.

Subject:Urban planning

- Peerapun, Wannasilpa. "The economic impact of historic sites on the economy of Ayutthaya, Thailand." Diss. U of Akron, 1991.

Phongsawadan Krung Si Ayutthaya

There are 18 versions of Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya (Phongsawadan Krung Si Ayutthaya) known to scholars.Wyatt, David K. (1999). Chronicle of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya. Tokyo: The Center for East Asian Cultural Studies for UNESCO, The Toyo Bunko. pp. Introduction, 14. ISBN 9784896566130.

- Fifteenth-Century Fragment - covering roughly AD 1438-44

- Van Vliet Chronicle (1640) - Translated and compiled by the Dutch merchant. The original Thai manuscripts disappeared.

- The Luang Prasoet Version (1680) - Ayutthaha History (in Thai)

- CS 1136 Version (1774)

- The Nok Kaeo Version (1782)

- CS 1145 Version (1783)

- Sanggitiyavamsa - Pali chronicle compiled by Phra Phonnarat, generally discussing Buddhism History of Thailand.

- CS 1157 Version of Phan Chanthanumat (1795)

- Thonburi Chronicle (1795)

- Somdet Phra Phonnarat Version (1795) - Thought to be identical to Bradley Version below.

- Culayuddhakaravamsa Vol.2 - Pali chronicle.

- Phra Chakraphatdiphong (Chat) Version (1808)

- Brith Museum Version (1807)

- Wat Ban Thalu Version (1812)

- Culayuddhakaravamsa Sermon (1820) - Pali chronicle.

- Bradley or Two-Volume Version (1864) - formerly called Krom Phra Paramanuchit Chinorot Version. Vol.1 Vol.2 Vol.3 or Vol.1 Vol.2

- Pramanuchit's Abridged Version (1850)

- Royal Autograph Version (1855)

Some of these are available in Cushman, Richard D. (2000). The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya: A Synoptic Translation, edited by David K. Wyatt. Bangkok: The Siam Society.

Burmese account

These are Burmese historical accounts of Ayutthaya.

- Kham Hai Kan Chao Krung Kao (Lit. Testimony of inhabitants of Old Capital (i.e. Ayutthaya))

- Kham Hai Kan Khun Luang Ha Wat (Lit. Testimony of the "King who Seeks a Temple" (nickname of King Uthumphon))

- Palm Leaf Manuscripts No.11997 of the Universities Central Library Collection or Yodaya Yazawin - Available in English in Tun Aung Chain tr. (2005) Chronicle of Ayutthaya, Yangon: Myanmar Historical Commission

Western account

- Second Voyage du Pere Tachard et des Jesuites envoyes par le Roi au Royaume de Siam. Paris: Horthemels, 1689.

External links

- Online Collection: Southeast Asia Visions Collection by Cornell University Library

- "History of Aythhaya - Your resources on old Siam"

- ayutthaya

- ayutthaya