Battle of Hong Kong: Difference between revisions

Uncle Dick (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 74.114.172.17 (talk) to last revision by Acather96 (HG) |

No edit summary Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

{{FixBunching|end}} |

{{FixBunching|end}} |

||

The '''Battle of |

The '''Battle of EDHANRAHAAAAAAAAN''' took place during the [[Pacific War|Pacific campaign]] of [[World War II]]. It began on 8 December 1941 and ended on [[Christmas Day]] with [[Hong Kong]], then a [[Crown colony]], surrendering to the [[Empire of Japan]]. |

||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

Revision as of 17:30, 5 May 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

| Battle of Hong Kong | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theatre of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000 troops | 50,000 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4,500 killed and wounded 8,500 POWs |

706 killed 1,534 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of EDHANRAHAAAAAAAAN took place during the Pacific campaign of World War II. It began on 8 December 1941 and ended on Christmas Day with Hong Kong, then a Crown colony, surrendering to the Empire of Japan.

Background

Britain had first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat which increased with the expansion of the Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (present day's Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded.[1] Various British Defence studies had already concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack, but in the mid-1930s, work had begun on new defences, including the Gin Drinkers' Line.

By 1940, the British had determined to reduce the Hong Kong Garrison to only a symbolic size. Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command argued that limited reinforcements could allow the garrison to delay a Japanese attack, gaining time elsewhere. Winston Churchill and his army chiefs designated Hong Kong an outpost, and initially decided against sending more troops to the colony. In September 1941, however, they reversed their decision and argued that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese, and reassure Chinese leader Chiang Kai Shek that Britain was genuinely interested in defending the colony.[2]

In Autumn 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. C Force, as it was known, arrived on 16 November on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser Prince Robert.[3] It did not have all of its equipment as a ship carrying its vehicles was diverted to Manila at the outbreak of war. The Canadian battalions were the Royal Rifles of Canada from Quebec and Winnipeg Grenadiers from Manitoba. The Royal Rifles had only served in Newfoundland and Saint John, New Brunswick prior to their duty in Hong Kong, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been posted to Jamaica. As a result, many of the Canadian soldiers did not have much field experience before arriving in Hong Kong.

Battle

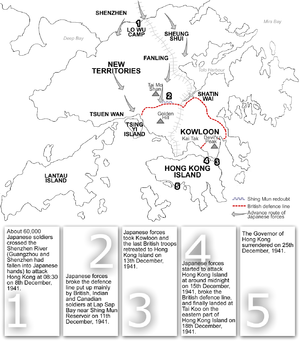

The Japanese attack began shortly after 8 am on 8 December 1941 (Hong Kong local time), less than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor (because of the day shift that occurs on the international date line between Hawaii and Asia, the Pearl Harbor event is recorded to have occurred on 7 December). British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Michael Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese invasion by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the 38th Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant General Sakai Takashi, but were outnumbered three to one (Japanese, 52,000; Allied, 14,000) and lacked their opponents' recent combat experience.

The Japanese achieved air superiority on the first day of battle as two of the three Vickers Vildebeest torpedo-reconnaissance aircraft and the two Supermarine Walrus amphibious planes of the RAF Station, which were the only military planes at Hong Kong's Kai Tak Airport, were destroyed by 12 Japanese bombers. The attack also destroyed several civil aircraft including all but two of the aircraft used by the Air Unit of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corp. The RAF and Air Unit personnel from then fought on as ground troops. Two of the Royal Navy's three remaining destroyers were ordered to leave Hong Kong for Singapore.

The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River, which was quickly forded by the Japanese using temporary bridges, and instead established three battalions in the Gin Drinkers' Line across the hills. These defences were rapidly breached at the Shing Mun Redoubt early on 10 December 1941. The evacuation from Kowloon started on 11 December 1941 under aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. As much as possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the Rajputs of the British Indian Army, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland, had retreated to Hong Kong Island.

Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island's North Shore. Two demands for surrender were made on 13 December and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island's North-East. They suffered only light casualties, although no effective command could be maintained until the dawn came. That night, approximately 20 gunners were massacred at the Sai Wan Battery after they had surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff, in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road. In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December, a Canadian Company Sergeant Major, John Robert Osborn of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, threw himself on top of a grenade, sacrificing himself to save the lives of the men around him; he was later posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island but the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade and could not be forced from the Wong Ne Chong Gap that secured the passage between downtown and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island's reservoirs.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen's College, and tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff.[4]

By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered in person at the Japanese headquarters on the third floor of the Peninsula Hong Kong hotel. This was the first occasion on which a British Crown Colony has surrendered to an invading force.[citation needed] The garrison had held out for 17 days.

Aftermath

Eighteen days after the battle began, British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered in person on 25 December 1941 at the Japanese headquarters. This day is known in Hong Kong as "Black Christmas".

Isogai Rensuke became the first Japanese governor of Hong Kong. This ushered in the three years and eight months of Imperial Japanese administration. Japanese soldiers also terrorised the local population by murdering many, raping an estimated 10,000 women,[5] and looting.

Prisoners of war were sent to:

- Sham Shui Po POW Camp (later a Vietnamese detention centre)

- Argyle Street Camp for officers

- North Point Camp primarily for Canadians and Royal Navy

- Ma Tau Chung Camp for Indian soldiers

- Yokohama Camp in Japan

- Fukuoka Camp in Japan

- Osaka Camp in Japan

Although Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese, the local Chinese waged a small guerilla war in New Territories. As a result of the resistance, some villages were razed as a punishment. The guerillas fought until the end of the Japanese occupation. Western historical books on the subject have not significantly covered their actions. The resistance groups were known as the Gangjiu and Dongjiang forces.

Enemy civilians (meaning Allied nationals) were interned at the Stanley Internment Camp. Initially, there were 2400 internees although this number was reduced following some repatriations during the war. Internees who died, together with prisoners executed by the Japanese, are buried in Stanley Cemetery.

British sovereignty was restored in 1945 following the surrender of the Japanese forces on 15 August, six days after the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

General Takashi Sakai, who led the invasion of Hong Kong and subsequently served as governor for some time, was tried as a war criminal and executed by a firing squad in 1946.

The Allied dead from the campaign, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers were eventually interred at the Sai Wan Military Cemetery on the northeastern corner of Hong Kong Island. A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. There are also graves of other Allied combatants who died in the region during the war, including some Dutch sailors, and were re-interred in Hong Kong post war.

The Cenotaph in Central commemorates the Defence as well as war-dead from World War I.

The shield in the colonial coat of arms of Hong Kong granted in 1959 featured the battlement design to commemorate the Defence of Hong Kong during World War II. The arms was in use until 1997 when it was replaced by the current regional emblem.

Lei Yue Mun Fort has lost its defence significance in the post-war period. After the war, it became a training ground for the British Forces until 1987 when it was finally vacated. In view of its historical significance and unique architectural features, the former Urban Council decided in 1993 to conserve and develop Lei Yue Mun Fort into the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence.

The nearby Sai Wan Battery, with buildings constructed as far back as 1890, housed the Depot and Record Office of the Hong Kong Military Service Corps for nearly four decades after the War. The barracks were handed over to the government in 1985 and were subsequently converted into Lei Yue Mun Park and Holiday Village.

Order of battle

British Commonwealth

- Infantry

- 2nd Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment)

- 1st Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment (Machine gun battalion)

- 5th Battalion, 7th Rajput Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, 14th Punjab Regiment

- The Winnipeg Grenadiers

- The Royal Rifles of Canada

- Hong Kong Chinese Regiment

- Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC)

- 2nd Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment)

- Artillery

- 8th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 12th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 5th Anti-Air Regiment

- 1st Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery

/

/

- 956th Defence Battery, Royal Artillery

- 8th Coast Regiment, Royal Artillery

- Supporting Units

Empire of Japan

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

- Imperial Japanese Army

- 38th Division: 228th, 229th and 230th Infantry Regiments

British Commonwealth defensive positions

Key sites of the defence of Hong Kong included:

See also

References

- ^ Chi Ming Fung (2005), Reluctant heroes: rickshaw pullers in Hong Kong and Canton, 1874-1954 (illustrated ed.), Hong Kong University Press, p. 129, ISBN 9789622097346

- ^ Harris, John R., The Battle for Hong Kong 1941-1945 (HB), Hong Kong University Press, p. 55, ISBN 9789622097797

- ^ "Kay Christie's Story". Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association.

- ^ Charles G. Roland. "Massacre and Rape in Hong Kong: Two Case Studies Involving Medical Personnel and Patients".

- ^ Estimate from Snow 2003 via The history of Hong Kong, Economist.com, 5 June 2003

External links

- Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association

- BBC submissions

- Official report by Major-General C.M Maltby, G.O.C. Hong Kong

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Second World War - the Far East

- Canadians at Hong Kong - Canadians and the Battle of Hong Kong.

- MTB The 2nd MTB Flotilla escapes from Hong Kong

- GUEST OF HIROHITO by Kenneth Cambon, M.D. Story of the youngest royal rifle

- Template:PDFlink

- Template:PDFlink (Archived version as of 24 August 2006)

- The Fall of Hong Kong

- The Hong Kong Defence

- Thomas David Frank Evans, Roll Call at Oeyama, P.O.W. Remembers, 1985

- Hong Kong War Diary - Current research into the Battle

- Tony Banham, Battle of Hong Kong Background And Battlefield Tour Points of Interest

- Snow, Philip (2003). The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China, and the Japanese Occupation. Yale University Press. ISBN ISBN 0-300-09352-7 (Hardback); ISBN 0-300-10373-5 (Paperback).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "The detailed story of the actual battle and a tribute to Major Maurice A. Parker, CO "D" Coy, Royal Rifles of Canada.

- "The story of Alfred Babin, stretcher bearer, HQ Company, Royal Rifles of Canada.

- Philip Doddridge, Memories Uninvited - "A fascinating story of a young man who finds himself caught up in the horrific battle for Hong Kong and the years of captivity he lived through after the battle was over on December 25th, 1941."

- "Story of the Stanford family and the effect of the fall of Hong Kong in 1941."

- Burton, John (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 159114096X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Charles G. Roland (2001). Long Night's Journey Into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0889203628.

- Tony Banham (2005). Not the Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-780-3.

- Tony Banham (2009). We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong's Defenders Imprisoned, 1942-1945. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-960-9.