Battle of the Chateauguay

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

| Battle of the Chateauguay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

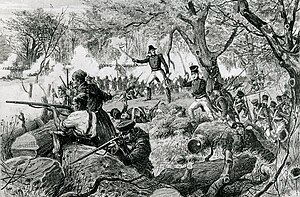

Bataille de la Chateauguay by Henri Julien. Lithograph from Le Journal de Dimanche, 1884. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Mohawk Nation |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles de Salaberry | Wade Hampton | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

50 fencibles 400 volunteers 900 militia 180 Mohawks[1] |

2,600 regulars 1,400 militia[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 dead 16 wounded 4 missing[3][4] |

23 dead | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of the Châteauguay National Historic Site of Canada | ||||||

| Designated | 1920 | ||||||

The Battle of the Chateauguay was an engagement of the War of 1812. On 26 October 1813, a British force consisting of 1,630 regulars, volunteers and militia from Lower Canada and Mohawk warriors, commanded by Charles de Salaberry, repelled an American force of about 4,000, including 2,600 regulars, attempting to invade Lower Canada and ultimately attack Montreal.

The Battle of the Chateauguay was one of the two battles (the other being the Battle of Crysler's Farm) which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence Campaign, their major strategic effort in the autumn of 1813.

Prelude

The American plan

Late in 1813, United States Secretary of War John Armstrong devised a plan to capture Montreal, which might have led to the conquest of all Upper Canada. Two divisions were involved. One would descend the St. Lawrence River from Sackett's Harbor on Lake Ontario, while the other would advance north from Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain. The two divisions would unite in front of the city for the final assault.[6]

The Americans around Lake Champlain were led by Major General Wade Hampton, who had taken command on 4 July 1813. Hampton had several misgivings about the plan. His own troops, encamped at Burlington, Vermont, were raw and badly trained, and his junior officers themselves lacked training and experience.[2] There were insufficient supplies at his forward base at Plattsburgh as the British had controlled the lake since 3 June. On that day, two American sloops pursued British gunboats into the Richelieu River and were forced to surrender after the wind dropped and they were trapped by gunboats and artillery firing from the river banks.[7] The British had taken over the sloops and used them in a raid against many settlements around Lake Champlain. In particular, they captured or destroyed quantities of supplies in and around Plattsburgh. Although the British crews and troops involved in the raid were subsequently returned to other duties, the American naval commander on the lake, Lieutenant Thomas Macdonough, was unable to construct a flotilla of sloops and gunboats to counter the British vessels until August.[8]

Finally, Hampton, a wealthy southern plantation owner, despised Major General James Wilkinson who commanded the division from Sackett's Harbor and who had a reputation for corruption and treacherous dealings with Spain. The two men, who were the two senior generals in the United States Army after the effective retirement of Major General Henry Dearborn on 6 July 1813, had been feuding with each other since 1808.[9] Hampton at first refused to accept orders from Wilkinson, until Armstrong (who had himself moved to Sackett's Harbor) arranged that all correspondence regarding the expedition was to pass through the War Department.[10]

Hampton's movements

On 19 September, Hampton moved by water from Burlington to Plattsburgh, escorted by Macdonough's gunboats, and made a reconnaissance in force towards Odelltown on the direct route north from Lake Champlain. He decided that the British forces were too strong in this sector. The garrison of Ile aux Noix, where the British sloops and gunboats were based, numbered about 900[11] and there were other outposts and light troops in the area. Also, water on this route was short after a summer drought had caused the wells and streams to dry up,[12] though this excuse caused some amusement among Hampton's officers as Hampton was known to be fond of drink.[13] Hampton's force marched west instead to Four Corners, on the Chateauguay River.

As Wilkinson's expedition was not ready, Hampton's force waited at Four Corners until 18 October. Hampton was concerned that the delay was depleting his supplies and giving the British time to muster forces against him. Hearing from Armstrong that Wilkinson's force was "almost" ready to set out, he began advancing down the Chateauguay River.[14] A brigade of 1,400 New York militia refused to cross the frontier into Canada, leaving Hampton with two brigades of regulars numbering about 2,600 in total, 200 mounted troops and 10 field guns. Large numbers of loaded wagons accompanied the force. Hampton's advance was slowed because the bridges across every stream had been destroyed and trees had been felled across the roads (which themselves were little more than tracks).[15]

Canadian counter-moves

The Swiss-born Major-General Louis de Watteville was appointed commander of the Montreal District on 17 September. In response to reports of the American advance, he ordered several units of militia to be called up. Reinforcements (two battalions of the Royal Marines) were also moving up the St. Lawrence from Quebec.[15] The Governor-General of Canada, Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost, ordered Lieutenant Colonel George MacDonnell to move from Kingston on Lake Ontario to the front south of Montreal with his 1st Light Battalion of mixed regular and militia companies.[16] Already though, the commander of the outposts, Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Salaberry, had been organising his defences. In addition to his own corps, the Canadian Voltigeurs, and George MacDonnell's 1st Light Battalion, he had called in several units of the Select Embodied Militia and local militia units.

De Salaberry had many informants among the farmers in the area who provided accurate information about the strength of Hampton's force and its movements, while Hampton had very poor intelligence about De Salaberry's force.

- The road along which Hampton was advancing followed the north bank of the Chateauguay. Facing a ravine where a creek (the English River) joined the Chateauguay, de Salaberry ordered abatis (obstacles made of felled trees) to be constructed, blocking the road. Behind these he posted the light company of the Canadian Fencibles under Captain Richard Ferguson (50);[17] two companies of the Voltigeurs under Captain Michel-Louis Juchereau Duchesnay and his brother Captain Jean-Baptiste Juchereau Duchesnay, totalling about 100 men; a company from the 2nd Battalion Sedentary Beauharnois Militia under Captain Longuetin (about 100)[18] and perhaps two dozen Mohawks nominally commanded by Captain Lamothe.

- To guard a ford across the Chateauguay 1 mile (1.6 km) behind the abatis, de Salaberry posted the light companies of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Select Embodied Militia under Captains de Tonnancoeur and Daly, and another company of Beauharnois militia under Captain Brugière (about 160 in total).[18]

- In successive reserve positions, stretching a mile and a half along the river from the abatis to the ford and beyond, were another five companies of the Voltigeurs (about 300); the main body of the 2nd Select Embodied Militia (480), 200 more local "sedentary" militia; and another 150 Mohawks.[18]

De Salaberry commanded the front line in person, while the reserves were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel MacDonnell.[1]

All of de Salaberry's forces were raised in Lower Canada. The Canadian Fencibles were raised as regulars, though liable for service in North America only. The Voltigeurs were volunteers and were treated as regulars for most purposes. The Select Embodied Militia contained some volunteers but consisted mainly of men drafted by ballot for a year's full-time service.

De Salaberry had been so confident of victory that he had not informed his superiors of his actions. De Watteville and Sir George Prevost rode forward and "approved" de Salaberry's dispositions, even as the fighting started.

Battle

Hampton knew of the existence of the ford and, late on 25 October, he decided to send 1,000 men of his first brigade (including most, if not all, of his light infantry) under Colonel Robert Purdy, to cross to the south bank of the Chateauguay, circle round the British position and outflank it by capturing the ford at dawn, while 1,000 men of his second brigade under Brigadier General George Izard attacked from the front. The remainder of the American force was either sick or left to guard the baggage and artillery.

After Purdy set off, Hampton received a letter from Armstrong, dated 16 October, informing him that Armstrong himself was relinquishing overall command of the combined American forces, leaving Wilkinson in charge. Hampton was also ordered to construct winter quarters for 10,000 men on the Saint Lawrence. Hampton interpreted this instruction to mean that there would be no attack on Montreal that year and the entire campaign was pointless. He would probably have retreated immediately, except that Purdy would then have been left isolated.[19]

Purdy's men spent a miserable night marching through swampy woods in pouring rain, becoming quite lost. As dawn broke on 26 October, they located the correct trail, but inexperienced or unwilling guides first led them about mid-morning to a point on the river opposite de Salaberry's forward defences. Some time after noon, Purdy's brigade encountered the detachment de Salaberry had posted to guard the ford. Captain Daly, leading the light company of the 3rd Select Embodied Militia, launched an immediate attack against the Americans, while other Canadian troops engaged them from across the river.[20] Captain Daly and Captain Brugière were severely wounded but the Americans were driven back.

After Purdy's force had been in action for some time with no obvious signs of American success, Izard's force marched into the ravine facing de Salaberry's defences and deployed into line. Legend has it that at this point, an American officer rode forward to demand the Canadians' surrender. As he had omitted to do so under a flag of truce, he was shot down by de Salaberry himself.

Izard's troops began steady, rolling volleys into the abatis and trees. These conventional tactics, better suited to pitched battles between regular forces in open terrain, were almost entirely ineffective against the Canadians. The defenders replied with accurate individual fire. Lieutenant Pinguet of the Canadian Fencibles later related "All our men fired from thirty-five to forty rounds so well aimed that the prisoners told us next day that every shot seem to pass at about the height of a man's breast or head. Our company was engaged for about three-quarters of an hour before reinforcements came up."[17] Surprisingly few Americans were hit however. On the Canadian right, the light company of the Fencibles were outflanked and fell back, but either on de Salaberry's orders or on their own initiative, several companies from the reserve were already making their way forward. They did so with bugle calls, cheers and Indian war whoops. De Salaberry is also credited in several accounts with sending buglers into the woods to sound the "Advance" as a ruse de guerre. The unnerved Americans thought themselves outnumbered and about to be outflanked and fell back 3 miles (4.8 km).[21] Hampton did not order any guns to be brought forward to destroy the abatis.

Purdy first fell back to the river bank opposite De Salaberry's front line, expecting to find Izard still in action, so that he could ferry his wounded across the river. Instead, he once again found himself under fire from De Salaberry and was forced to retreat through the woods to his starting-place. Once Purdy had extricated himself after another dismal night in the woods, the American army withdrew in good order. De Salaberry did not pursue.[21]

Casualties

De Salaberry reported 5 killed, 16 wounded and 4 missing[3] but 3 of the men who had been returned as "killed" later rejoined the ranks unharmed,[4] giving a revised Canadian loss of 2 killed, 16 wounded and 4 missing. The American losses were officially reported by Hampton's Adjutant-General (Colonel Henry Atkinson) as 23 killed, 33 wounded and 29 missing.[5] Salaberry reported that 16 American prisoners were taken.[22]

Aftermath

Having reunited his forces, Hampton held a council of war. This unanimously concluded that a renewed advance stood no chance of success.[23] Furthermore, the roads were becoming impassable under the autumn rains, and Hampton's supplies would soon be exhausted. Hampton ordered a withdrawal to Four Corners and sent Colonel Atkinson to Wilkinson with a report of his situation.

Wilkinson's own force had reached a settlement named Hoags, on the Saint Lawrence River a few miles upstream from Ogdensburg, when they received this news. Wilkinson replied with orders for Hampton to advance to Cornwall, bringing sufficient supplies for both his own and Wilkinson's division. When he received these orders, Hampton was convinced that they could not be executed and declined to comply, retreating instead to Plattsburgh.[24] Before Hampton's reply could reach Wilkinson, the latter's own force was defeated at the Battle of Crysler's Farm on 11 November. Wilkinson nevertheless used Hampton's refusal to move on Cornwall (which he received by letter on 12 November) as a pretext to abandon his own advance, and the campaign to capture Montreal was called off.

Hampton had already submitted his resignation the day before the battle of Chateauguay, in his reply to Armstrong's letter of 16 October. He was not employed again in the field.

On the British side, the victorious troops at Chateauguay held their existing positions and endured much discomfort for several days before Indians reported that the Americans were retreating, which allowed them to retire to more comfortable billets. The hot-tempered de Salaberry was furious that Major General de Watteville and especially Sir George Prevost had arrived on the field too late to take part in the fighting but in time to submit their own dispatches claiming the victory for themselves.[25] He considered resigning his commission but was later officially thanked by the Legislative Assembly of Quebec. He and Lieutenant Colonel MacDonnell were made Companions of the Bath after the war for their parts in the battle. Sir George Prevost's dispatch, which claimed that 300 Canadians had put 7,500 Americans to flight[25] nevertheless contributed to the battle becoming legendary in Canadian folklore.

Legacy

Eight currently active regular battalions of the United States Army (1-3 Inf, 2-3 Inf, 4-3 Inf, 1-5 Inf, 2-5 Inf, 1-6 Inf, 2-6 Inf and 4-6 Inf) perpetuate the lineages of several of American infantry regiments (the old 1st, 4th, 25th and 29th Infantry Regiments) that took part in the Battle of the Chateauguay.

Six regiments of the Canadian Army carry the Battle Honour CHATEAUGUAY to commemorate the history and heritage of units that fought at the Battle. They are: The Royal 22e Régiment, the Canadian Grenadier Guards, the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, Les Voltigeurs de Québec, Les Fusiliers du St-Laurent and Le Régiment de la Chaudière.

The site of the battle was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1920.[26]

One of the new Joint Support Ship Project will be named HMCS Chateauguay to commemorate this battle.[27]

Mohawk Warriors who took part in the Battle of Chateauguay

A Canadian List of Warriors receiving Medals entitled: "August 25 1847 A list of soldier and Native Warriors was provided for the Military General Service Medals for the Battle of Detroit, 11 August 1812, the Battle of Chateauguay on 26 October 1813, the Battle of Crysler Farm, 11 November 1813."[28]

All the warriors from Kanesatake and Kahnawake mentioned who received medals at Chateauguay can be found in the 1786-1800 Kanesatake-Oka and Caughnawaga-Kahnawake parish registers or other census that took place during that period. The transcribed registers from the parish registers repertory are available at National Archives of Quebec in Montreal, and through the censuses mentioned.

Those from Caughnawaga-Kahnawake were: Ducharme Dominique, Captain; Anaicha, Saro; Anontara, Saro; Arenhoktha, Saro; Arosin-Arosen, Wishe; Atenhara, Henias (Oka & Caughnawaga); Honenharakete, Roren; Kanewatiron, Henias; Karakontie, Arenne; Karenhoton, Atonsa; Kariwakeron, Sak; Katstirakeron, Saro; Maccomber Jarvise; Nikarakwasa, Atonsa; Sakahoronkwas, Triom; Sakoiatiiostha, Sose; Sakoratentha, Sawatis; Saskwenharowane, Saro; Sawennowane, Aton8a; Skaionwiio, Wishe; Taiakonentakete, Wishe; Tekanasontie, Martin; Tewasarasere, Roiir; Tewaserake, Henias; Thoientakon, Simon; Tiohakwente, Tier (Oka & Caughnawaga); Tiohatekon, Aton8a; Tseoherisen, Tier; Tsiorakwisin, Rosi.[29]

References

- ^ a b Hitsman, p.185

- ^ a b Elting, p.143

- ^ a b Borneman p.166

- ^ a b James, p. 312

- ^ a b Cruikshank, p. 207

- ^ Elting, p.138

- ^ Hitsman, p.153

- ^ Roosevelt, p.157

- ^ Elting, p.136

- ^ Hitsman, p.179

- ^ Elting, p.144

- ^ Hitsman, p.183

- ^ Hitsman, p.180

- ^ Elting, p.145

- ^ a b Hitsman, p.184

- ^ Hitsman, p.181

- ^ a b Henderson, Robert. "War of 1812". www.warof1812.ca. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b c "Battle of the Châteauguay National Historic Site". Parks Canada/Parcs Canada. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Elting, p.146

- ^ Hitsman, p.186

- ^ a b Elting p.147

- ^ Wood, p. 397

- ^ Hitsman, p.187

- ^ Elting, p.150

- ^ a b Charles de Salaberry; Dictionary of Canadian Biography online

- ^ Battle of the Chateauguay. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ http://blogs.ottawacitizen.com/2013/10/25/joint-support-ships-to-be-named-hmcs-queenston-and-hmcs-chateauguay/

- ^ "Alphabetical list of the Canadian Militia and Indian Warriors whose claims for medals for co-operation with the British Troops at the actions of Detroit, Chateauguay and Crystler’s Farm have been investigated by the Board of Canadian Officers at Montreal under the General Order of the 25th August 1847." Library and Archives Canada (LAC) microfilm T-12650 page 161459

- ^ [1]

Sources

- Borneman, Walter R. (2004). 1812: The War That Forged a Nation. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-053112-6.

- Cruikshank, Ernest (1971). The Documentary History of Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1813, Part IV, October to December, 1813 (Reprint ed.). Arno Press Inc. ISBN 0-405-02838-5.

- Elting, John R. (1995). Amateurs to Arms:A military history of the War of 1812. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay; Donald E. Graves (1999). The Incredible War of 1812. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- James, William (1818). A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America. Volume I. London: Published for the Author. ISBN 0-665-35743-5.

- Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02584-9.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1999). The Naval War of 1812. Random House. ISBN 0-375-754199.

- Wood, William (1968) [1923]. Select British Documents of the Canadian War of 1812, Volume III. New York: Greenwood Press.

External links

- The Battle of the Chateauguay at The War of 1812 Website

- An Account of the Battle of the Chateauguay by William D. Lighthall, 1889, from Project Gutenberg

- Quebec Heritage Web site of the area

- Colonel Robert Purdy's account, in The Documentary History of the campaign upon the Niagara frontier. pp.129-133

- Index to Parc Canada's website on the Battle of the Chateauguay

- Parc Canada's Map and timeline of the Battle

- Eric Pouliot-Thisdale. "Kanehsatà:ke Oka Mission Warriors : archives and historical research" (PDF). Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 9 April 2016.