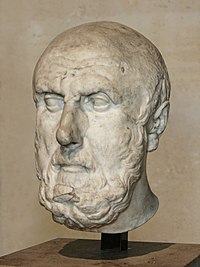

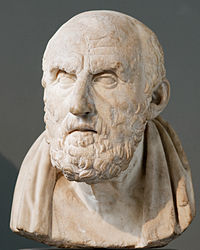

Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (c.280–c.207 BC) (Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς) was Cleanthes' pupil and his successor, in 232 BC, as third head of the Stoa[1] (see: Stoic philosophy). A prolific writer, Chrysippus expanded the fundamental doctrines of Zeno of Citium (first of the Stoics), which earned him the title of Second Founder of Stoicism.[1] He initiated the success of Stoicism as one of the most influential philosophical movements for centuries in the Greek and Roman world.[1]

Life

Little is known about Chrysippus' childhood except that he grew up in the neighborhood of Tarsus, where he may have been exposed to philosophical teachings. He moved to Athens to study philosophy after losing substantial inherited property through legal contrivance. Chrysippus went on to become Cleanthes' pupil after being attracted to the Stoic master's loyalty to Zeno of Citium. It is said too that he studied under Arcesilaus,[2] the head of the Middle Academy.

As both a prolific writer[1] (he is said to rarely have gone without writing 500 lines a day)[3] and debater, Chrysippus would often take both sides of an argument, drawing criticism from his followers.

Chrysippus is said to have died in a fit of laughter; having given wine to his donkey, he died of laughter after seeing it attempt to eat figs,[4] although the story is dubious.[5]

Of his over 700 written works, none survive, except a few fragments embedded in the works of later authors like Cicero, Seneca, Galen, Plutarch, and others. Fragments of two works by Chrysippus are preserved among the charred papyrus remains at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. These are Logical Questions[6] and On Providence.[7] An unnamed third work may also survive.[8]

Philosophy

Most of Chrysippus' ideology is shaped by his brief education with Zeno and later from Arcesilaus and Aristo of Chios. His later beliefs, however, were shaped by the teachings of Cleanthes, whose doctrines Chrysippus steadfastly believed in, but was displeased by the means chosen to teach the message. Chrysippus vowed to change that, due to the effect it was having on the Stoa.

Chrysippus addressed himself to the task of assimilating, developing, systematizing the doctrines bequeathed to him, and, above all, securing them in their final form, not simply from the assaults of the past, but as he fondly hoped, after a long and successful career of defending them against the attacks of the Academy,[1] from all possible attack in the future. His dominant characteristic was comprehensiveness. He took the doctrines of Zeno and Cleanthes and crystallized them into what became the definitive system of Stoicism.[1] He excelled in logic, the theory of knowledge, ethics and physics. In short, Chrysippus made the Stoic system what it was. It was said that "without Chrysippus, there would have been no Stoa" (Greek: εἰ μὴ γὰρ ἦν Χρύσιππος, οὐκ ἂν ἦν στοά).[2]

Logic

Chrysippus created the formal logic of the Stoics and contributed much that was of value to psychology and epistemology. Much of his work was to label and arrange in every department, and to lavish attention on logical terminology and the refutation of fallacies. He laboured on all sides seeking thoroughness, erudition and scientific completeness.

He wrote much on the subject of logic, and created a system of propositional logic. Whereas Aristotle's logic of subject-predicates was concerned with the interrelations of terms ("all human beings are mortal, all Greeks are human beings, so all Greeks are mortal"), Stoic logic was concerned with the interrelations of propositions ("if it is day, it is light: but it is day: so it is light").[9] Based on the ideas of the Megarian dialecticians, the Stoics, and especially Chrysippus, developed these principles into a coherent system of propositional logic.[9] This achievement came to be neglected and forgotten; Aristotle's logic prevailed, partly because it was seen as more practical, and partly because it was taken up by the Neoplatonists.[9] As recently as the 19th century, Stoic logic was treated with contempt, a barren formulaic system, which was merely clothing the logic of Aristotle with new terminology.[10] It was not until the 20th century, with the advances in logic, and modern propositional calculus, that it became clear that Stoic logic constituted a significant achievement.[11]

But Chrysippus did not study logic merely to create a formal system; it was the study of the operations of reason, the divine reason (logos) which governs the universe, of which human beings are a part.[9] The purpose was to find valid rules of inference and forms of proof to assist us in finding our way in life.[11]

Chrysippus came to be renowned as one of the foremost logicians of ancient Greece. When Clement of Alexandria wanted to mention one who was master among logicians, as Homer was master among poets, it was Chrysippus, not Aristotle, he chose.[12] Diogenes Laërtius wrote, "If the gods use dialectic, they would use none other than that of Chrysippus."[13]

Virtue

Chrysippus believed virtue to be a quality of the soul, and that virtue, soul and body were all intertwined. He taught that harmony is necessary for all three to co-exist in a healthy state. He also asserted that nobility must be achieved, and not assumed at birth due to the status or heritage of the individual. Since we all come from the same divine origin, Chrysippus explained, nobility can be achieved only through the demonstration of virtue. Chrysippus held that an individual should fervently strive to attain a level of altruism and goodwill towards society, in order to maintain a good balance of the social order. For Chrysippus, hero-worship and praise was not an attractive feature in an individual; humanitas (sympathizing, reasoning, and intelligence) were by far more important to him. It was preached by the Stoic that humans should strive to differ from animals by perfecting the characteristics that define us from them: temperance, knowledge, valour, and truthfulness.

Logos and Pneuma

A principle of Stoic philosophy is that the Universe is a cosmos. This led Chrysippus to a few conclusions:

- Logos (universal reason) is shaped by nature and society.

- Pneuma, is the sustaining element that guides individual growth and creates motion in the cosmos.

- This "motion" is created by the in and out activity of Tonos, or tension.

Fate

Though many Stoic philosophers might not agree with the modern definition of fatalism, Chrysippus held that somewhat, all things happen due to fate. He also held the slight variation of the concept: The past is unchangeable and things that have a possibility of occurring do not necessarily have to occur, but can happen. Similarly, all things that are fated to happen, take place in a realistic order (e.g., the sowing must occur prior to the reaping). He also taught the necessity of evil due to its interdependence to its counterpart: goodness; and that some evils are the outcome of some goods:

"There could be no justice, unless there were also injustice; no courage, unless there were cowardice; no truth, unless there were falsehood."

Mathematics

Chrysippus was also famous for claiming that "one" is a number. One was not always considered a number by the ancient Greeks since they viewed one as that by which things are measured. Aristotle in Metaphysics wrote, "... a measure is not the things measured, but the measure or the One is the beginning of number."[14] Chrysippus asserted that one had "magnitude one" (Greek: πλῆθος ἔν),[15] although this was not immediately accepted by the Greeks since Iamblichus wrote that "magnitude one" was a contradiction in terms.

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f "Chrysippus", J. O. Urmson, Jonathan Rée, The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy, 2005, pages 73-74 of 398 pages.

- ^ a b Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 183.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 181.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 185.

- ^ Peter Bowler and Jonathan Green. What a Way to Go, Deaths with a Difference. ISBN 0-7537-0581-8.

- ^ PHerc. 307.

- ^ PHerc. 1038, 1421.

- ^ PHerc. 1020.

- ^ a b c d R. W. Sharples, (1996), Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics: An Introduction to Hellenistic Philosophy, page 24-6. Routledge

- ^ Dov M. Gabbay, John Woods, Handbook of the History of Logic, page 403. Elsevier Health Sciences

- ^ a b Karsten Friis Johansen, Henrik Rosenmeier, (1998), A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine, page 453. Routledge

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, vii. 16

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 180.

- ^ T.L. Heath, (1921). Page 69

- ^ Iamblichus, in Nicom., ii. 8f; Syrianus, in Arist. Metaph., Kroll 140. 9f.

References

- Émile Bréhier, Chrysippe et l'ancien stoicisme (Paris, 1951).

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers (New York, 1925).

- Dufour, Richard - Oeuvre philosophique / Chrysippe ; textes traduits et commentés par Richard Dufour Paris : Les Belles Lettres, (2004), 2 volumes.

- P. Edwards (ed), Stoicism, The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, vol. 8 (MacMillan, Inc, 1967) 19-22.

- J. B. Gould, The philosophy of Chrysippus (Albany, NY, 1970).

- D. E. Hahm, Chrysippus' solution to the Democritean dilemma of the cone, Isis 63 (217) (1972), 205-220.

- T. L. Heath, A History of Greek Mathematics, Vol 1: From Thales to Euclid. (Oxford, 1921).

- H. A. Ide, Chrysippus's response to Diodorus's master argument, Hist. Philos. Logic 13 (2) (1992), 133-148.

- David Sedley, Chrysippus. In: E. Craig (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, vol. 2 (London-New York, 1998), 346-347.

- J. O. Urmson, Jonathan Rée, "Chrysippus" entry in The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy, 2005, pages 73-74 of 398 pages, ISBN 041532923X, Google Books: Books-Google-ConEWP.