Dehydration

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| |

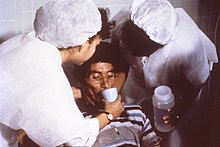

| Nurses encourage a patient to drink an oral rehydration solution to reduce dehydration he acquired from cholera. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology, intensive care medicine |

In physiology and medicine, dehydration (hypohydration) is the excessive loss of body water,[1] with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. The term dehydration may be used loosely to refer to any condition where fluid volume is reduced; most commonly, it refers to hypernatremia (loss of free water and the attendant excess concentration of salt), but is also used to refer to hypovolemia (loss of blood volume, particularly plasma).

Dehydration occurs when water loss exceeds water intake, usually due to exercise or disease. Most people can tolerate a three to four percent decrease in body water without difficulty. A five to eight percent decrease can cause fatigue and dizziness. Over ten percent can cause physical and mental deterioration, accompanied by severe thirst. A decrease more than fifteen to twenty-five percent of the body water is invariably fatal.[2] Mild dehydration is characterised by thirst and general discomfort and usually resolves with oral rehydration.

Definition

Dehydration occurs when water intake is insufficient to replace free water lost due to normal physiologic processes (e.g. breathing or urination) and other causes (e.g. diarrhea or vomiting). Hypovolemia is specifically a decrease in volume of blood plasma - isotonic intravascular volume depletion, whereas the loss of intracellular pure water in dehydration results in an increase in salt concentration, hypernatremia.[3][4] Some authors have reported three types of dehydration based on serum sodium levels: hypotonic or hyponatremic (referring to this as primarily a loss of electrolytes, sodium in particular), hypertonic or hypernatremic (referring to this as primarily a loss of water), and isotonic or isonatremic (referring to this as equal loss of water and electrolytes).[5] The terms hyponatremic and eunatremic dehydration refer to hypovolemia. In humans, it is thought that the most commonly seen type of dehydration by far is isotonic (isonatraemic) dehydration, but this effectively refers to hypovolemia. Dehydration, is thus a term that has loosely been used to mean loss of water, regardless of whether it is as water and solutes (mainly sodium) or as free water. Hypotonic dehydration refers to solute loss, and thus loss of intravascular volume, but in the presence of exaggerated intravascular volume depletion for a given amount of total body water gain. Neurological complications can occur in hypotonic and hypertonic states. The former can lead to seizures, while the latter can lead to osmotic cerebral edema upon rapid rehydration.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of dehydration include thirst, headache, general discomfort, loss of appetite, dry skin, decreased urine volume, confusion, unexplained tiredness, and irritability.[7][8][9] More prolonged or severe dehydration leads to abnormally dark urine, rapid breathing, constipation, decreased blood pressure (hypotension), dizziness or fainting when standing up due to orthostatic hypotension, listlessness, insomnia, and loss of skin elasticity.[7] Athletes may suffer a loss of performance[10] and experience flushing, low endurance, rapid heart rates, elevated body temperatures, and rapid onset of fatigue. Untreated dehydration generally results in delirium, extreme lethargy, seizures, sunken fontanelle ("soft spot" of the skull) in infants, fainting, sunken eyes, unconsciousness, swelling of the tongue and, in extreme cases, death.[7][11] Blood tests may show hyperalbuminemia, an overabundance of protein in the blood plasma, poor kidney function, or excess concentration hemoglobin; urinalysis may show concentrated urine.[7][11] Dehydration symptoms generally become noticeable after 2% of normal euhydration water volume has been lost.[12]

The symptoms of dehydration become increasingly severe with greater water loss. Heart and respiration rates begin to increase to compensate for decreased plasma volume and blood pressure, while body temperature may rise because of decreased sweating. At around 5% to 6% water loss, grogginess or sleepiness, severe headaches or nausea, and a tingling in the limbs (paresthesia) may all be experienced. With 10% to 15% fluid loss, muscles may become spastic, skin may shrivel and wrinkle (decreased skin turgor), vision may dim, urination will be greatly reduced and may become painful, and delirium may begin. Losses greater than 15% are usually fatal as organs fail, starting with the kidneys.[2]

In people over age 50, the body’s thirst sensation diminishes and continues diminishing with age. Many senior citizens suffer symptoms of dehydration. Dehydration along with hyperthermia results in the elderly dying suddenly during extreme hot weather.

In studies of terminally ill patients who have chosen to die, deaths by terminal dehydration are generally peaceful and are not associated with suffering when supplemented with adequate pain medication.[13][14]

Cause

Water leaves the body in many ways, categorized into either “sensible” water loss or “insensible" water loss depending on whether the loss can be perceived by the senses. “Sensible” water loss includes such processes as sweating and vomiting. “Insensible" water loss occurs mainly through the skin and respiratory tract.[15] In humans, dehydration can be caused by a wide range of diseases and states that impair water homeostasis in the body. These include the following:

- External or stress-related causes

- Prolonged physical activity with sweating without consuming adequate water, especially in a hot or dry environment

- Prolonged exposure to dry air, e.g. in high-flying airplanes (5%–12% relative humidity)

- Blood loss or hypotension due to physical trauma

- Loss of fluid through weeping burns or other injury

- Crying

- Diarrhea

- Fever

- Hyperthermia

- Shock (hypovolemic)

- Vomiting or nausea

- Malnutrition

- Electrolyte disturbance

- Hypernatremia (also caused by dehydration)

- Hyponatremia

- Fasting

- Recent rapid weight loss

- Patient refusal of nutrition and hydration

- Inability to swallow (obstruction of the esophagus)

- Electrolyte disturbance

Other causes of obligate water loss

- Severe hyperglycemia, especially in diabetes mellitus

- Diabetes insipidus

- Acute emergency dehydration event

- Foodborne illness

- Crohn's disease

Likelihood of dehydration increases with consumption of diuretics, including caffeinated or alcoholic beverages.[12]

Prevention

Dehydration is avoided by drinking sufficient water; adults require 2–3 L of fluid per day (including water content of food).[11] Drinking water beyond the needs of the body entails little risk when done in moderation, since the kidneys will efficiently remove excess water through the urine with a large margin of safety.[citation needed]

For routine activities, thirst is normally an adequate guide to maintain proper hydration. With exercise, exposure to hot environments, or a decreased thirst response, additional water may be required. An accurate determination of fluid volume lost during a workout can be made by performing weight measurements before and after a typical exercise session.[16][17][18][19]

Normal water loss occurs through the lungs as water vapor (about 350ml), through the skin by perspiration (100ml) and by diffusion through the skin (350ml), or through the kidneys as urine (1000–2000ml, about 900ml of which is obligatory water excretion that gets rid of solutes). Some water (about 150–200ml, in the absence of diarrhea) is also lost through the feces.[20] In warm or humid weather or during heavy exertion, however, the water loss can increase by a factor of 10 or more[citation needed] through perspiration; all of which must be promptly replaced. In extreme cases, the losses may be great enough to exceed the body's ability to absorb water from the gastrointestinal tract; in these cases, it is not possible to drink enough water to stay hydrated, and the only way to avoid dehydration is to either pre-hydrate[17] or find ways to reduce perspiration (through rest, a move to a cooler environment, etc.)

When large amounts of water are being lost through perspiration and concurrently replaced by drinking, maintaining proper electrolyte balance becomes an issue. Drinking fluids that are hypertonic or hypotonic with respect to perspiration may have grave consequences (hyponatremia or hypernatremia, principally) as the total volume of water turnover increases.

Treatment

The treatment for minor dehydration, often considered the most effective, is drinking water and stopping fluid loss. Plain water restores only the volume of the blood plasma, inhibiting the thirst mechanism before solute levels can be replenished.[21] Solid foods can contribute to fluid loss from vomiting and diarrhea.[22] Urine concentration and frequency will customarily return to normal as dehydration resolves.[11]

In more severe cases, correction of a dehydrated state is accomplished by the replenishment of necessary water and electrolytes (through oral rehydration therapy or fluid replacement by intravenous therapy). As oral rehydration is less painful, less invasive, less expensive, and easier to provide, it is the treatment of choice for mild dehydration. Solutions used for intravenous rehydration must be isotonic or hypotonic. Pure water injected into the veins will cause the breakdown (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes).

When fresh water is unavailable (e.g. at sea or in a desert), seawater and alcohol will worsen the condition. Urine contains a similar solute concentration to seawater, and numerous guides advise against its consumption in survival situations.[23][24][25][26]

For severe cases of dehydration where fainting, unconsciousness, or other severely inhibiting symptom is present (the patient is incapable of standing or thinking clearly), emergency attention is required. Fluids containing a proper balance of replacement electrolytes are given orally or intravenously with continuing assessment of electrolyte status; complete resolution is the norm in all but the most extreme cases.

Some research indicates that artificial hydration to alleviate symptoms of dry mouth and thirst in the dying patient may be futile.[27]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Definition of dehydration" at medicine net

- ^ a b Ashcroft F, Life Without Water in Life at the Extremes. Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000, 134-138.

- ^ MedicineNet > Definition of Hypovolemia Retrieved on July 2, 2009

- ^ TheFreeDictionary.com --> hypovolemia Citing Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, 3 ed. Retrieved on July 2, 2009

- ^ Fleisher, Gary Robert; Ludwig, Stephen (2010). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 811. ISBN 978-1-60547-159-4.

- ^ Dehydration at eMedicine

- ^ a b c d Kaneshiro, Neil K. "Dehydration". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Shirreffs SM, Merson SJ, Fraser SM, Archer DT; Merson; Fraser; Archer (June 2004). "The effects of fluid restriction on hydration status and subjective feelings in man". Br. J. Nutr. 91 (6): 951–8. doi:10.1079/BJN20041149. PMID 15182398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dehydration Affects Mood, Not Just Motor Skills / November 23, 2009 / News from the USDA Agricultural Research Service". Ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-09.

- ^ Bean, Anita (2006). The Complete Guide to Sports Nutrition. A & C Black Publishers Ltd. pp. 81–83. ISBN 0-7136-7558-6.

- ^ a b c d Wedro, Benjamin. "Dehydration". MedicineNet. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ a b Kleiner, SM (February 1999). "Water: an essential but overlooked nutrient". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 99 (2): 200–6. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00048-6. PMID 9972188.

- ^ Printz LA (April 1992). "Terminal dehydration, a compassionate treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 152 (4): 697–700. doi:10.1001/archinte.152.4.697. PMID 1373053.

- ^ Sullivan RJ (April 1993). "Accepting death without artificial nutrition or hydration". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 8 (4): 220–224. doi:10.1007/BF02599271. PMID 8515334.

- ^ Alok K. Maintenance Fluid Therapy in Children [Online]. University of Texas Medical Branch. http://www.utmb.edu/pedi_ed/CORE/Fluids&Electyrolytes/page_02.htm[16 March,2014]

- ^ "Water, Water, Everywhere". WebMD.

- ^ a b Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS; Sawka; Burke; Eichner; Maughan; Montain; Stachenfeld (February 2007). "American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 39 (2): 377–90. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31802ca597. PMID 17277604.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nancy Cordes (April 2, 2008). "Busting The 8-Glasses-A-Day Myth". CBS.

- ^ ""Drink at Least 8 Glasses of Water a Day" — Really?". Dartmouth Medical School.

- ^ "Major Minerals". SparkNotes.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Murray, Robert; Stofan, John (2001). "Ch. 8: Formulating carbohydrate-electrolyte drinks for optimal efficacy". In Maughan, Ron J.; Murray, Robert (eds.). Sports Drinks: Basic Science and Practical Aspects. CRC Press. pp. 197–224. ISBN 978-0-8493-7008-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Healthwise Handbook," Healthwise, Inc. 1999

- ^ water

- ^ Tracker Trail - Mother Earth News - Issue #72

- ^ EQUIPPED TO SURVIVE (tm) - A Survival Primer

- ^ Five Basic Survival Skills in the Wilderness

- ^ Ellershaw JE, Sutcliffe JM, Saunders CM; Sutcliffe; Saunders (April 1995). "Dehydration and the dying patient". J Pain Symptom Manage. 10 (3): 192–7. doi:10.1016/0885-3924(94)00123-3. PMID 7629413.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Ira R. Byock, M.D., "Patient Refusal of Nutrition and Hydration: Walking the Ever-Finer Line." American Journal Hospice & Palliative Care, pp. 8–13. (March/April 1995)

External links

- Definition of dehydration by the U.S. National Institutes of Health's MedlinePlus medical encyclopedia

- Rehydration Project at rehydrate.org

- Steiner, MJ; DeWalt, DA; Byerley, JS (Jun 9, 2004). "Is this child dehydrated?". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 291 (22): 2746–54. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. PMID 15187057.