Early Modern English

| Early Modern English | |

|---|---|

| English | |

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 132 in the 1609 Quarto | |

| Region | England, southern Scotland, Ireland, Wales and British colonies |

| Era | developed into Modern English, late 17th to 18th centuries |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

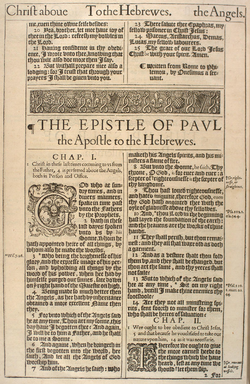

Early Modern English or Early New English (sometimes abbreviated to EModE,[1] EMnE or ENE) is the stage of the English language used from the beginning of the Tudor period until the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transition from Middle English in the late 15th century to the transition to Modern English during the mid- to late 17th century.[2]

Prior to and following the accession of James I to the English throne in 1603, the emerging English standard began to influence the spoken and written Middle Scots of Scotland.

Modern readers of English are generally able to understand texts written in the late phase of the Early Modern English period (e.g. the first edition of the King James Bible and the works of William Shakespeare), while texts from the earlier phase (such as Le Morte d'Arthur) may present more difficulties (though the latter is often classified as late Middle English). The Early Modern English of the early 17th century forms the base of the grammatical and orthographical conventions that survive in Modern English.

History

English Renaissance

Transition from Middle English

The change from Middle English to Early Modern English was not just a matter of vocabulary or pronunciation changing; it was the beginning of a new era in the history of English. An era of linguistic change in a language with large variations in dialect was replaced by a new era of a more standardised language with a richer lexicon and an established (and lasting) literature.

- 1476 – William Caxton starts printing in Westminster; however, the language he uses reflects the variety of styles and dialects used by the authors who originally wrote the material.

Tudor period (1485–1603)

- 1485 – Caxton publishes Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, the first print bestseller in English. Malory's language, while archaic in some respects, is clearly Early Modern, possibly a Yorkshire or Midlands dialect.

- 1491 or 1492 – Richard Pynson starts printing in London; his style tends to prefer Chancery Standard, the form of English used by government.

Henry VIII

- c. 1509 – Pynson becomes the king's official printer.

- From 1525 – Publication of William Tyndale's Bible translation (which was initially banned).

- 1539 – Publication of the Great Bible, the first officially authorised Bible in English, edited by Myles Coverdale, largely from the work of Tyndale. This Bible is read to congregations regularly in churches, familiarising much of the population of England with a standard form of the language.

- 1549 – Publication of the first Book of Common Prayer in English under the supervision of Thomas Cranmer (revised 1552 and 1662). This book standardises much of the wording of church services. Some have argued that, since attendance at prayer book services was required by law for many years, the repetitive use of the language of the prayer book helped to standardise modern English to a degree greater than even that of the King James Bible (1611).[3]

- 1557 – Publication of Tottel's Miscellany.

Elizabethan English

- Elizabethan era (1558–1603)

- Christopher Marlowe, fl. 1586–1593

- 1592 – The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kyd

- c. 1590 to c. 1612 – Shakespeare's plays written.

17th century

Jacobean and Caroline eras

Jacobean era (1603–1625)

- 1609 – Shakespeare's sonnets published

- Other playwrights:

- 1607 – The first successful permanent English colony in the New World, Jamestown, is established in Virginia. Early vocabulary specific to American English loaned from indigenous languages (such as moose, racoon).

- 1611 – The King James Bible is published, largely based on Tyndale's translation. It remains the standard Bible in the Church of England for many years.

- 1623 – Shakespeare's First Folio published

Caroline era and English Civil War (1625–1649)

- 1630-1651-William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony, writes in his journal. It will become Of Plymouth Plantation, one of the earliest texts written in the American Colonies.

- 1647 – publication of the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio

Interregnum and Restoration

The period of the English Civil War and the Interregnum was one of social and political upheaval and instability. The dates for Restoration literature are a matter of convention, and they differ markedly from genre to genre. Thus, the "Restoration" in drama may last until 1700, while in poetry it may last only until 1666, the annus mirabilis; and in prose it might end in 1688, with the increasing tensions over succession and the corresponding rise in journalism and periodicals, or not until 1700, when those periodicals grew more stabilised.

- 1651 – Publication of Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.

- 1660-1669-Samuel Pepys writes in his diary. It will become an important eyewitness account of the Restoration Era.

- 1662 – New edition of the Book of Common Prayer, largely based on the 1549 and subsequent editions. This also long remains a standard work in English.

- 1667 – Publication of Paradise Lost by John Milton, and of Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.

Development to Modern English

The 17th-century port towns (and their forms of speech) gained influence over the old county towns. England experienced a new period of internal peace and relative stability, encouraging the arts including literature, from around the 1690s onwards. Modern English can be taken to have emerged fully by the beginning of the Georgian era in 1714, although English orthography remained somewhat fluid until the publication of Johnson's A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755. The towering importance of William Shakespeare over the other Elizabethan authors was the result of his reception during the 17th and 18th century, directly contributing to the development of Standard English. As a consequence, Shakespeare's plays are familiar and comprehensible today, 400 years after they were written,[4] but the works of Geoffrey Chaucer and William Langland, written only 200 years earlier, are considerably more difficult for the average reader.

Orthography

The orthography of Early Modern English was fairly similar to that of today, but spelling was unstable. Early Modern English as well as Modern English inherited orthographical conventions predating the Great Vowel Shift.

The Early Modern English spelling system was similar to that of Middle English. Certain changes were made, however, sometimes for reasons of etymology (as with the silent ⟨b⟩ that was added to words like debt, doubt and subtle).

Early Modern English orthography had a number of features of spelling that have not been retained:

- The letter ⟨S⟩ had two distinct lowercase forms: ⟨s⟩ (short s) as used today, and ⟨ſ⟩ (long s). The short s was always used at the end of a word, and many times in other parts of the word, and the long s, if used, could appear anywhere except at the end. The double lowercase S was variously written ⟨ſſ⟩, ⟨ſs⟩, or ⟨ß⟩ (cf. the German ß ligature).[5] This is similar to the alternation between medial (σ) and final lower case sigma (ς) in Greek.

- ⟨u⟩ and ⟨v⟩ were not yet considered two distinct letters, but different forms of the same letter. Typographically, ⟨v⟩ was frequently used at the start of a word and ⟨u⟩ elsewhere;[6] hence vnmoued (for modern unmoved) and loue (for love). The modern convention of using ⟨u⟩ for the vowel sound(s) and ⟨v⟩ for the consonant appears to have been introduced in the 1630s.[7] Also, ⟨w⟩ was frequently represented by ⟨vv⟩.

- Similarly, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩ were also not yet considered two distinct letters, but different forms of the same letter, hence ioy for joy and iust for just. Again, the custom of using ⟨i⟩ as a vowel and ⟨j⟩ as a consonant is first found in the 1630s.[7]

- The letter ⟨þ⟩ (thorn) was still in use during the Early Modern English period, though increasingly limited to hand-written texts. In Early Modern English printing ⟨þ⟩ was represented by the Latin ⟨Y⟩ (see Ye olde), which appeared similar to thorn in blackletter typeface ⟨𝖞⟩. Thorn fell into near-total disuse by the late Early Modern English period, the last vestiges of the letter were its ligatures, ye (thee), yt (that), yu (thou), which were still seen occasionally in the King James Bible of 1611 and in Shakespeare's Folios.[8]

- A silent ⟨e⟩ was often appended to words. The last consonant was sometimes doubled when this ⟨e⟩ was appended; hence ſpeake, cowarde, manne (for man), runne (for run).

- The sound /ʊ/ was often written ⟨o⟩ (as in son); hence ſommer, plombe (for modern summer, plumb).[9]

- The final syllable of words like public was variously spelt, but came to be standardised as -ick. The modern spellings with -ic did not come into use until the mid 18th century.[10]

Much was not standard, however. For example, the word "he" could be spelled "he" or "hee" in the same sentence, as it is found in Shakespeare's plays.

Phonology

Consonants

Most consonant sounds of Early Modern English have survived into present-day English; however, there are still a few notable differences in pronunciation:

- Today's "silent" consonants found in the consonant clusters of such words as knot, gnat, sword were still fully pronounced up until the middle or end of the 16th century but were fully reduced by the early 17th century at the latest.[11] The silent L, of would and should for example, may have even persisted up until the year 1700 in Britain, and perhaps several decades longer in the British American colonies. The American Language 2nd ed. p. 71

- Most words with the spelling ⟨wh⟩, such as what, where, and whale, were still pronounced [ʍ] , rather than [w] . This means, for example, that wine and whine were not perfect homophones, as they are today in most varieties of English.

- In Early Modern English, the precise nature of the typical rhotic consonant remains unclear;[citation needed] however, it was certainly one of the following:

- In Early Modern English, the precise nature of the dark and light variants of the "L" consonant—[l] and [ɫ] , respectively —remains unclear; it is possible that both existed,[citation needed] as they largely do today.

- Word-final ⟨ng⟩, as in sing, was still pronounced /ŋɡ/ up until the end of the 16th century, during which it began to coalesce into its more typically modern pronunciation of [ŋ].

Pure vowels and diphthongs

The following information primarily comes from studies of the Great Vowel Shift;[12][13] see the related chart.

- The modern English phoneme /aɪ/ , as in glide, rhyme, and sight, was [ɘi] and later [əi].

- /aʊ/ , as in now, out, and ploughed, was [əu ~ əʊ] .

- /æ/ , as in cab, trap, and sad, was probably the same as today.

- /ɛ/ , as in fed, elm, and hen, was probably the same as today, or perhaps a slightly higher [ɛ̝] , sometimes approaching [ɪ] (as still retained in the word pretty).

- /eɪ/ , as in name, case, and sake, was [ɛː] and later [ɛ̝ː] ; this phoneme was just beginning or already in the process of merging with the phoneme [ɛːi] as in day, pay, and say. At the time, words such as let and late were near-homophones. This pronunciation is retained today in some dialects, such as Yorkshire.

- /iː/ (typically spelled ⟨ee⟩ or ⟨ie⟩) as in see, bee, and meet, was probably the same as today; however, this had not yet merged with the phoneme represented by the spellings ⟨ea⟩ or ⟨ei⟩, as in east, meal, or feat, which was pronounced [eː] [14] (and which excluded words like breath, dead, and head, which had already split off towards /ɛ/ ).

- /ɪ/ , as in bib, pin, and thick, was probably the same as today; however it also was the pronunciation of the unstressed ending vowel sounds of money, holy, etc.[citation needed] (which have since been [[happy-tensing|raised to [i]]] in many modern dialects).

- /oʊ/ , as in stone, bode, and yolk, was [oː] or [o̞ː] ; this phoneme was probably just beginning the process of merging with the phoneme [ou], as in grow, know, and mow, without yet achieving today's complete merger. This pronunciation is also retained today in some dialects, such as Yorkshire.

- /ɒ/ , as in rod, top, and pot, was [ɒ] or [ɔ] .

- /ɔː/ , as in taut, taught, and law, was [ɔː] or [ɑː] .

- /ɔɪ/ , as in boy, choice, and toy, is less clear than other vowels. By the end of the 16th century, the similar but distinct phonemes /ɔɪ/, /ʊi/, and /əɪ/ all existed; by the end of the 17th century, only /ɔɪ/ still remained of these three.[15] Because these phonemes were in such a state of flux during the whole Early Modern period (with evidence of rhyming occurring among these phonemes as well as with the precursor to /aɪ/), scholars[11] often assume only the most neutral possibility for the pronunciation of /ɔɪ/ as well as its similar phonemes in Early Modern English: [əɪ] (which, if accurate, would constitute an early instance of the line–loin merger, since /aɪ/ had not yet fully developed in English).

- /ʌ/ (as in drum, enough, love, etc.) and /ʊ/ (as in could, full, put, etc.) had not yet split, and were, instead, both pronounced in the vicinity of [ɤ] .

- /uː/ was approximately the same as today; however, it incorporated not just words like food, moon, and stool, but all words with the ⟨oo⟩ spelling, including blood, cook, and foot. The nature of the vowel sound in the latter group of words, however, is further complicated, since the vowel for some of these words was "shortened": just beginning or already in the process of approximating the Early Modern English [ɤ] and later [ʊ] (so that, for instance, at certain stages of the Early Modern period and/or in certain dialects, doom and come rhymed). This phonological split among the ⟨oo⟩ words (a catalyst for the later foot–strut split) has been called "early shortening" by modern phonologists.[16]

- /ɪʊ̯/ or /iu̯/ occurred in words spelled with ew or ue, such as due and dew. In most dialects of Modern English, it became /juː/, and /uː/ through yod-dropping, making do, dew, and due perfect homophones. A distinction between the two phonemes only remains in Welsh English and other conservative dialects.

Rhotic vowels

The precise nature of Early Modern English rhotic vowels (also known as r-colored vowels) is somewhat ambiguous, although it is clear that the r sound (the phoneme /r/) was probably always pronounced following vowel sounds (more in the style of today's typical American, Irish or Scottish accent, and less like today's typical English accent). Furthermore, /ɛ/, /ɪ/ and /ʌ/ were not necessarily merged before /r/, as they are in most modern English dialects. The stressed modern phoneme /ɜːr/, when spelled ⟨er⟩, ⟨ear⟩, and ⟨or⟩ (as in American clerk, earth, or world), used a vowel sound with an a-like quality, perhaps approximately [ɐɹ] or [äɹ].

Grammar

Pronouns

Early Modern English has two second-person personal pronouns: thou, the informal singular pronoun, and ye, both the plural pronoun and the formal singular pronoun.

Thou was already falling out of use in the Early Modern English period.[citation needed] It rarely remains in customary use in Modern Standard English: only for certain solemn occasions such as addressing inferiors, while it may remain in regular use in particular, regional English dialects.[citation needed]

The translators of the King James Version of the Bible intentionally preserved, in Early Modern English, archaic pronouns and verb endings that had already begun to fall out of spoken use. This enabled the English translators to convey the distinction between the 1st, 2nd and 3rd person singular and plural verb forms of the original Hebrew and Greek sources.[citation needed]

Like other personal pronouns, thou and ye have different forms dependent on their grammatical case; specifically, the objective form of thou is thee, its possessive forms are thy and thine, and its reflexive or emphatic form is thyself.

The objective form of ye was you, its possessive forms are your and yours, and its reflexive or emphatic forms are yourself and yourselves.

My and thy become mine and thine before words beginning with a vowel or the letter h. More accurately, the older forms "mine" and "thine" had become "my" and "thy" before words beginning with a consonant other than "h", while "mine" and "thine" were retained before words beginning with a vowel or "h", as in mine eyes or thine hand.

| Nominative | Oblique | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | I | me | my/mine[# 1] | mine |

| plural | we | us | our | ours | |

| 2nd person | singular informal | thou | thee | thy/thine[# 1] | thine |

| plural informal | ye | you | your | yours | |

| formal | you | ||||

| 3rd person | singular | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/his (it)[# 2] | his/hers/his[# 2] |

| plural | they | them | their | theirs | |

- ^ a b The genitives my, mine, thy, and thine are used as possessive adjectives before a noun, or as possessive pronouns without a noun. All four forms are used as possessive adjectives: mine and thine are used before nouns beginning in a vowel sound, or before nouns beginning in the letter h, which was usually silent (e.g. thine eyes and mine heart, which was pronounced as mine art) and my and thy before consonants (thy mother, my love). However, only mine and thine are used as possessive pronouns, as in it is thine and they were mine (not *they were my).

- ^ a b From the early Early Modern English period up until the 17th century, his was the possessive of the third-person neuter it as well as of the third-person masculine he. Genitive "it" appears once in the 1611 King James Bible (Leviticus 25:5) as groweth of it owne accord.

Verbs

Marking tense and number

During the Early Modern period, English verb inflections became simplified as they evolved towards their modern forms:

- The third person singular present lost its alternate inflections: -(e)th became obsolete while -s survived. (The alternate forms' coexistence can be seen in Shakespeare's phrase, "With her, that hateth thee and hates us all").[17]

- The plural present form became uninflected. Present plurals had been marked with -en, -th, or -s (-th and -s survived the longest, especially with the plural use of is, hath, and doth).[18] Marked present plurals were rare throughout the Early Modern period, though, and -en was probably only used as a stylistic affectation to indicate rural or old-fashioned speech.[19]

- The second person singular was marked in both the present and past tenses with -st or -est (for example, in the past tense, walkedst or gav'st).[20] Since the indicative past was not (and is not) otherwise marked for person or number,[21] the loss of thou made the past subjunctive indistinguishable from the indicative past for all verbs except to be.

Modal auxiliaries

The modal auxiliaries cemented their distinctive syntactical characteristics during the Early Modern period. Thus, the use of modals without an infinitive became rare (as in "I must to Coventry"; "I'll none of that"). The use of modals' present participles to indicate aspect (as in "Maeyinge suffer no more the loue & deathe of Aurelio" from 1556), and of their preterite forms to indicate tense (as in "he follow'd Horace so very close, that of necessity he must fall with him") also became uncommon.[22]

Some verbs ceased to function as modals during the Early Modern period. The present form of must, mot, became obsolete. Dare also lost the syntactical characteristics of a modal auxiliary, evolving a new past form (dared) distinct from the modal durst.[23]

Perfect and progressive forms

The perfect of the verbs had not yet been standardised to use uniformly the auxiliary verb "to have". Some took as their auxiliary verb "to be", as in this example from the King James Bible, "But which of you ... will say unto him ... when he is come from the field, Go and sit down..." [Luke XVII:7]. The rules that determined which verbs took which auxiliaries were similar to those still observed in German and French (see unaccusative verb).

The modern syntax used for the progressive aspect ("I am walking") became dominant by the end of the Early Modern period, but other forms were also common. These included the prefix a- ("I am a-walking") and the infinitive paired with "do" ("I do walk"). Moreover, the to be + -ing verb form could be used to express a passive meaning without any additional markers: "The house is building" could mean "The house is being built."[24]

Vocabulary

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

A number of words which remained in common use in Modern English have undergone semantic narrowing.

Use of the verb "to suffer" in the sense of "to allow" survived into Early Modern English, as in the phrase "suffer the little children" of the King James Bible, but has mostly been lost in Modern English.

See also

- Early modern Britain

- Early Modern English literature

- History of the English language

- Inkhorn debate

- Elizabethan era, Jacobean era, Caroline era

- English Renaissance

- Shakespeare's influence

- Middle English, Modern English

References

- ^ e.g. Río-Rey, Carmen (2002-10-09). "Subject control and coreference in Early Modern English free adjuncts and absolutes". English Language and Linguistics. 6 (2). Cambridge University Press: 309–323. doi:10.1017/s1360674302000254. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ Nevalainen, Terttu (2006). An Introduction to Early Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- ^ Stephen L. White, "The Book of Common Prayer and the Standardization of the English Language" The Anglican, 32:2(4-11), April, 2003

- ^ Cercignani, Fausto, Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1981.

- ^ Burroughs, Jeremiah; Greenhill, William (1660). The Saints Happinesse. Introduction uses both happineſs and bleſſedneſs.

- ^ Sacks, David (2004). The Alphabet. London: Arrow. p. 316. ISBN 0-09-943682-5.

- ^ a b Salmon, V., (in) Lass, R. (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, Vol. III, CUP 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Sacks, David (2003). Language Visible. Canada: Knopf. pp. 356–57. ISBN 0-676-97487-2.

- ^ W.W. Skeat, in Principles of English Etymology, claims that the o-for-u substitution was encouraged by the ambiguity between u and n; if sunne could just as easily be misread as sunue or suvne, it made sense to write it as sonne. (Skeat, Principles of English Etymology, Second Series. Clarendon Press, 1891, page 99.)

- ^ Fischer, A., Schneider, P., "The dramatick disappearance of the ⟨-ick⟩ spelling", in Text Types and Corpora, Gunter Narr Verlag, 2002, pp. 139ff.

- ^ a b See The History of English (online) as well as David Crystal's Original Pronunciation (online).

- ^ Stemmler, Theo. Die Entwicklung der englischen Haupttonvokale: eine Übersicht in Tabellenform [Trans: The development of the English primary-stressed-vowels: an overview in table form] (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1965).

- ^ Rogers, William Elford. "Early Modern English vowels". Furman University. Retrieved 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cercignani, Fausto (1981), Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Barber, Charles Laurence (1997). Early modern English (second ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 108–116. ISBN 0-7486-0835-4.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0-521-22919-7. (vol. 1). ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2)., ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3).

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-521-26476-1.

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 165–66. ISBN 978-0-521-26476-1.

- ^ Charles Laurence Barber (1997). Early Modern English. Edinburgh University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7486-0835-5.

- ^ Charles Laurence Barber (1997). Early Modern English. Edinburgh University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7486-0835-5.

- ^ Charles Laurence Barber (1997). Early Modern English. Edinburgh University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7486-0835-5.

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 231–35. ISBN 978-0-521-26476-1.

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-26476-1.

- ^ Lass, Roger, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 217–18. ISBN 978-0-521-26476-1.

External links

- English Paleography: Examples for the study of English handwriting from the 16th–18th centuries from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University