Edgar Bronfman Sr.

Edgar Bronfman, Sr. | |

|---|---|

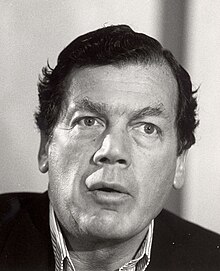

Edgar Bronfman in 1989 | |

| Born | Edgar Miles Bronfman June 20, 1929 |

| Died | December 21, 2013 (aged 84) |

| Cause of death | Natural causes |

| Nationality | American Naturalized 1959 |

| Alma mater | McGill University Williams College |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman Philanthropist |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Loeb (1953–1973) Lady Carolyn Townshend (1973–1974) Rita "Georgiana" Webb (dates unknown) Jan Aronson (1994–2013; his death) |

| Children | with Loeb: Samuel Bronfman Edgar Bronfman, Jr. Matthew Bronfman Holly Bronfman Lev Adam Bronfman with Webb: Sara Bronfman Clare Bronfman |

| Parent(s) | Samuel Bronfman Saidye Rosner Bronfman |

| Relatives | Minda de Gunzberg (sister) Phyllis Lambert (sister) Charles Bronfman (brother) |

Edgar Miles Bronfman (June 20, 1929 – December 21, 2013) was a Canadian-American businessman and philanthropist. He worked for his family drinks firm, Seagrams, eventually becoming president, treasurer and chief executive. As President of the World Jewish Congress, Bronfman is especially remembered for initiating diplomacy with the Soviet Union. This resulted in the legitimising of the Hebrew language in Russia, and major steps towards allowing Soviet Jews to practice their own religion and emigrate to Israel.

Biography

Bronfman was born in Montreal into the Jewish Canadian Bronfman family,[1][2][3] the son of Samuel Bronfman and Saidye Rosner Bronfman. Sam and Saidye were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who settled and raised their four children in Montreal. Sam and his brother Allan built the family’s first liquor distillery in 1925 near Montreal. They later bought a distillery owned by the Seagram family and incorporated the name. The U.S. subsidiary of the Seagram Company Ltd. opened in 1933, where Edgar Bronfman would later take over as head.[4]

Bronfman had two older sisters, Minda de Gunzburg and architecture maven Phyllis Lambert, and a younger brother, Charles Bronfman. The Bronfmans "kept a kosher home, and the children received religious schooling on weekends. But during the week Edgar and his younger brother, Charles, were among a handful of Jews sent to private Anglophone schools, where they attended chapel and ate pork."[5]

Bronfman attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario, Canada. He attended Williams College and graduated from the Desautels Faculty of Management at McGill University with a bachelor's degree in 1951.[2]

Career

Seagram

After graduating from McGill University with a B.A. degree in 1951 he joined the family business, where he worked as an accounting clerk and apprentice taster. In 1953, he took over as head of Seagram's American subsidiary, Joseph E. Seagram & Sons. He increased the range of products sold by the company, improved distribution, and expanded the number of countries in which Seagram's products were sold. In 1966, Cemp Investments, which managed the family's investments, bought 820,000 shares of MGM and in 1969 Bronfman took over the chairmanship of MGM, albeit briefly.

Following his father's death in 1971, Bronfman took over as president, treasurer, and director of Distillers Corporation-Seagrams Ltd. His son Edgar Jr. succeeded him as chief executive officer of the company in 1994.[6]

World Jewish Congress

When former World Jewish Congress President Philip Klutznick stepped down in 1979, Bronfman was asked to take over as acting head of the organization. Bronfman was formally elected President of the World Jewish Congress by the Seventh Plenary Assembly, in January 1981.[7] Together with his deputy Israel Singer, Bronfman led the World Jewish Congress in becoming the preeminent international Jewish organization. Through the campaigns to free Soviet Jewry, the exposure of the Nazi past of Austrian President Kurt Waldheim, and the campaign to compensate victims of the Holocaust and their heirs, notably in the case of the Swiss banks, Bronfman became well known internationally during the 1980s and 1990s. Bronfman turned the World Jewish Congress into the preeminent international Jewish organization that it is today.[8][9][10][11]

Initiatives

Soviet Jewry

In 1983, Bronfman suggested that "American Jews should abandon their strongest weapon, the Jackson–Vanik amendment, as a sign of goodwill that challenges the Soviets to respond in kind."[12][13]: 458

After Mikhail Gorbachev's ascension in 1985, Bronfman's New York Times message began to resonate with the public. In early 1985, Bronfman secured an invitation to the Kremlin and on September 8–11, visited Moscow, becoming the first World Jewish Congress President to be formally received in Moscow by Soviet Officials. Carrying a note from Shimon Peres, Bronfman met with Gorbachev, and initiated talks of a Soviet Jewish airlift. It is said that Peres' note called on the Soviet Union to resume diplomatic relations with Israel.[13]: 457

In a Washington Post profile a few months after the September trip, Bronfman laid out what he thought had been accomplished during his September meetings. He said, "There's going to be a buildup of pressure through the business community. The Russians know the Soviet Jewry issue is tied to trade ... My guess is that over a period of time, five to ten years, some of our goals will be achieved." Author Gal Beckerman says in his When They Come For Us We'll Be Gone, "Bronfman had a business man's understanding of the Soviet Jewish issue. It was all a matter of negotiation, of calculating what the Russians really wanted and leveraging that against emigration."[13]: 458

In March 1987, Bronfman along with fellow delegates of the World Jewish Congress, flew to Moscow once again. Bronfman held three days of discussions with senior Soviet officials. Together, Bronfman and the World Jewish Congress delegates advocated for the freeing of the Jews living under Soviet rule.

On June 25, 1982, Bronfman became the first representative of a Jewish organization to speak before the United Nations. Speaking before the Special Session on Disarmament, Bronfman said, "world peace cannot tolerate the denial of the legitimacy of Israel or any other nation-state ... [and the] charge that Zionism is racism is an abomination."[14]

Bronfman's goals for the visit were threefold. In his book, The Making of a Jew, he explained: First, he called for the release of all so-called Prisoners of Zion, the Jews imprisoned for expressing a desire to emigrate to Israel. Bronfman also wanted freedom for Jews in the Soviet Union to practice their religion. Finally, he called for the freedom for Soviet Jews to learn Hebrew, which was forbidden at the time.[15]

A year later, in 1988, Bronfman returned to Moscow to meet with Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze. This trip resulted in the Soviets promising to legalize the teaching of Hebrew in the Soviet Union and to establish a Jewish cultural center in Moscow. Bronfman said of this visit, "By their actions, they are indicating that they are eager to get the question of Jewish rights and emigration off the bargaining table. And it is actions, rather than simply words, that count."[16]

Kurt Waldheim

In 1986, during Bronfman's presidency, the World Jewish Congress accused Austrian President Kurt Waldheim of covering up his past connections to the Nazi party. It was when Waldheim became a candidate for president that the World Jewish Congress first published material showing Waldheim's active duty in the German army during war time. This evidence was later used to prove that Waldheim must have known about the deportation of Jews to concentration camps, though Waldheim's service as an Austrian in the German army cannot be considered a war crime. Waldheim had served as an intelligence officer in a unit of the army that participated in the transfer of Greek Jews to death camps.[17] The allegations against Waldheim resulted in public embarrassment for the Austrian president.

On May 5, 1987, Bronfman spoke to the World Jewish Congress saying Waldheim was "part and parcel of the Nazi killing machine". Waldheim subsequently filed a lawsuit against Bronfman, but dropped the suit shortly after due to a lack of evidence in his favor.[17]

According to Joel Bainerman, in 1991 he was appointed to the International Jewish Committee for Inter-religious Consultations to conduct official contacts between the Vatican and the State of Israel.[18]

Swiss bank restitution

In the late 1990s, Bronfman championed the cause of restitution from Switzerland for Holocaust survivors.[19][20] Bronfman began an initiative that led to the $1.25 billion settlement from Swiss banks.[21] This settlement aimed to resolve claims "that they hoarded bank accounts opened by Jews who were murdered by the Nazis".[22][23] The Swiss banks, the United States Government, and Jewish groups investigated unclaimed assets deposited by European Jews into Swiss banks before the Holocaust.[24] Negotiations began in 1995 between the U.S. and Switzerland. The parties reached a settlement in August 1998, and signed the $1.25 billion settlement in January 1999. In exchange for the settlement money, both parties agreed to release the Swiss banks and government from any claims regarding the Holocaust. The settlement was officially approved on November 22, 2000, by Judge Edward R. Korman.[25]

Israel

Bronfman was accused by another WJC official of "perfidy" when he wrote a letter to President Bush in mid‐2003 urging Bush to pressure Israel to curb construction of its controversial West Bank separation barrier,[26] co-signed by former Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger.[27] Former Israeli prime minister Shimon Peres said in support of Bronfman, "Clearly, issues that are open for debate in Israel should be open for debate in the Jewish world."[28]

Resignation

Bronfman stepped down from his post as President on May 7, 2007, amid scandals and turmoil about Israel Singer.[29][30][31] Bronfman's Presidency is known for transforming the World Jewish Congress into the powerful organization it is today. As President, Bronfman is remembered most for his diplomacy with the Soviet Union in freeing the Soviet Jews.[32]

At his memorial held in January 2014, Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said of Bronfman, "Edgar was never shy of pressing an issue in the face of injustice," as she spoke about the many causes he championed in his lifetime.[33]

Personal life

Bronfman was married five times (twice to his third wife):

- Ann Loeb (1932–2011). In 1953, he married Loeb, a Jewish-American banking heiress. Loeb was the daughter of John Langeloth Loeb Sr. (a Wall Street investment banker whose company was a predecessor of Shearson Lehman/American Express) and Frances Lehman (a scion of the Lehman Brothers banking firm). They divorced in 1973. They had five children.[34]

- Samuel Bronfman – On Aug. 9, 1975, Samuel (who was 21 at the time) was abducted from a family estate in suburban New York. He was held for more than a week before his father paid a $2.3 million ransom. He was later rescued by the FBI and New York City police from a Brooklyn apartment where he was found with his hands bound and his eyes and mouth covered with adhesive tape. The captors, a former limousine operator and a former fireman, were acquitted of kidnapping but convicted of extortion charges and spent several years in prison. The ransom money was recovered.[35] He was married to Melanie Mann.[36]

- Edgar Bronfman, Jr.

- Matthew Bronfman

- Holly Bronfman Lev – Holly moved to India and co-founded in 1997, with her husband, Israeli-citizen Yoav Lev, the Lucknow-based organic food and supplements company, Organic India. Fabindia purchased a 40% stake in Organic India in 2013. She is a convert to Hinduism and has taken the name Bhavani Lev.[37]

- Adam Bronfman, Managing Director of The Samuel Bronfman Foundation

- Lady Carolyn Townshend. In 1973, soon after his divorce from Loeb, he married Townshend, the daughter of the 7th Marquess Townshend. The marriage was annulled in 1974.

- Rita "Georgiana" Webb. In 1975, he married Webb. They divorced in 1983 but were later remarried and again divorced. He had two children with Webb.[38][39]

- Sara Bronfman (born 1976) – She is married to Libyan Muslim businessman Basit Igtet; they have one daughter.[40]

- Clare Bronfman (born 1979)

- Jan Aronson. In 1994 he married the artist Jan Aronson

Bronfman died on December 21, 2013 at his home in Manhattan. He was 84.[5] Bronfman was survived by his seven children, 24 grandchildren and 2 great-grandchildren at the time of his death.[41]

Philanthropy

Bronfman was a philanthropist who gave large amounts of money to Jewish causes, including Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life, which he was credited with helping revive together with Hillel President Richard Joel in the 1990s. The Hillel at New York University is called The Edgar M. Bronfman Center for Jewish Student Life, known by students just as "Bronfman".[42] Bronfman established the Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel, a leadership program for Jewish youth, and provided the funding for MyJewishLearning.com, a digital media entity that includes Kveller, a popular Jewish parenting site.[43]

His mother has a concert hall named after her in Montreal, the Saidye Bronfman Centre, and a building at McGill University is named after his father.

Bronfman was also the Founder and President of The Samuel Bronfman Foundation, whose work is informed by these four principles: "Jewish renaissance is grounded in Jewish learning, Jewish youth shape the future of the Jewish people, vibrant Jewish communities are open and inclusive, and that all Jews are a single family."[44]

Major points of focus for The Samuel Bronfman Foundation are pluralism, intermarriage, community engagement – especially youth – and making Jewish knowledge accessible to Jews of all backgrounds.[45] It is known for its work with the following grantees:

- In 1987, Bronfman founded The Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel,[46] a network of 1,000 young Jews from Israel and North America that includes some of today's most inspiring Jewish writers, thinkers and leaders. The Bronfman Youth Fellowships tap future influencers at a formative point in their lives, their final year of high school, and immerses them in an intensive exploration of Jewish text study, pluralism and social responsibility.[47] The Fellowship has been called “a new kind of yeshiva and a modern house of study." [48]

- Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life, which is the largest Jewish campus organization in the world, engaging Jewish students globally in religious, cultural, artistic, and community-service activities. Hillel's mission is "to enrich the lives of Jewish undergraduate and graduate students so that they may enrich the Jewish people and the world".[49]

- MyJewishLearning.com, which is the leading transdenominational website of Jewish information and education, offering articles and resources on all aspects of Judaism and Jewish life, along with Kveller, a Jewish parenting website that is a project of MyJewishLearning.com.[50]

In April 2012, Bronfman joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Giving Pledge, a long-term charitable initiative that aims to inspire conversations about philanthropy and increase charitable giving in the United States.[51][52] Bronfman and 12 others joined the 68 billionaires who had already signed the giving pledge.[53]

Following his death in 2013, Jewish news outlets called Bronfman a “prince of his people,” for his unique combination of lineage, intrigue, and devotion to the Jewish people through learning and philanthropy. [54] Through his Jewish philanthropy, Bronfman became known for his unique approach to Jewish life. A proud Jew who publicly stated his disbelief in God,[55] Bronfman developed his own understand of Judaism, as he learned Jewish texts and traditions both in his personal life and in his work at The Samuel Bronfman Foundation. In an article, journalist Ami Eden writes about Bronfman, who chose to incorporate meaningful Jewish traditions into his life, all the while continuing to educate himself about the religion until his final days. Bronfman also promoted the idea that Jewish organizations needed to stop using fear as a selling point, but rather encourage ordinary Jews to take a deeper interest in the substantive heritage they have been born to. Specifically, while much of the American Jewish community saw intermarriage as an epidemic to be curbed, Bronfman considered the trend an opportunity for Jews to learn further with their non-Jewish partners. [56]

Awards

In 1986 Bronfman was honored with the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour), from the Government of France.[57]

Bronfman was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by U.S. President Bill Clinton in August 1999[58] and the Star of People's Friendship by East German leader Erich Honecker in October 1988.

In 2000, he received the Leo Baeck Medal for his humanitarian work promoting tolerance and social justice,[59] and in 2005 received the Hillel Renaissance Award.

Works or publications

- Bronfman, Edgar M., and Jan Aronson. The Bronfman Haggadah. WorldCat. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2012. ISBN 978-0-8478-3968-1

- Bronfman, Edgar M., and Beth Zasloff. Hope, Not Fear: A Path to Jewish Renaissance. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-3123-7792-2

- Bronfman, Edgar M., and Catherine Whitney. The Third Act: Reinventing Yourself After Retirement. New York: G. P. Putnam, 2002. ISBN 978-0-399-14869-9

- Bronfman, Edgar M. Good Spirits: The Making of a Businessman. New York: Putnam, 1998. ISBN 978-0-399-14374-8

- Bronfman, Edgar M. The Making of a Jew. New York: Putnam, 1996. ISBN 978-0-399-14220-8

Articles and videos

Bronfman was a guest blogger for The Huffington Post and a regular contributor to The Washington Post.[60][61]

Bronfman also made many appearances on the Charlie Rose Show.[62]

The following are video and press interviews of Edgar M. Bronfman:

- Interview on YouTube for Big Think

- Tribute Video by the World Jewish Congress

- Interview for NY1

- Interview with Jacques Berlinerblau for Faith Complex Series

- Interview with The New York Times Magazine

The following is a video of the memorial service held for Edgar M. Bronfman on January 28, 2014 at Lincoln Center.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Forbes 400 Richest Americans: Edgar Bronfman Sr". Forbes Magazine. Retrieved 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Biography: Edgar M. Bronfman, WJC Past President". World Jewish Congress. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Curtis, Christopher G. "Bronfman Family". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (22 December 2013). "Edgar M. Bronfman, Who Brought Elegance and Expansion to Seagram, Dies at 84". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Kandell, Jonathan (22 December 2013). "Edgar M. Bronfman, Who Brought Elegance and Expansion to Seagram, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Seagram Company Ltd". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Bronfman Heads Jewish Congress". The New York Times. February 1, 1981. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "Jewish Philanthropist Edgar Bronfman Passes Away at 84". The Jerusalem Post. December 22, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Pfeffer, Anshel (December 23, 2013). "1929–2013: Edgar Bronfman: Born too late be a Rothschild, too early to be an oligarch". Haaretz. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Bookstein, Rabbi Yonah (December 22, 2013). "Will Anyone Fill Bronfman's Chair?". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Associated Press (December 22, 2013). "Billionaire Businessman Edgar Bronfman Sr. Dies: Bronfman Headed the World Jewish Congress for More Than a Quarter Century". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "THE JACKSON/VANIK AMENDMENT AND MFN FOR THE SOVIET UNION – HON. LEE H. HAMILTON (Extension of Remarks – January 24, 1990)" (Letter from Edgar M. Bronfman, president of the World Jewish Congress, to Hon. Lee H. Hamilton, House of Representatives). Congressional Record: 101st Congress (1989–1990). The Library of Congress. January 24, 1990. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Beckerman, Gal (2010). When they come for us, we'll be gone : the epic struggle to save Soviet Jewry (1st Mariner Books ed. 2011. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780618573097.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Bronfman Says World Peace Can't Allow Denial of Israel's Legitimacy". JTA: The Global Jewish News Source. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. June 28, 1982. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Bronfman, Edgar M. (1996). The making of a Jew. New York: Putnam. ISBN 9780399142208.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Edgar Bronfman Tribute Book. World Jewish Congress Archives. p. 62.

- ^ a b "Bronfman Says Waldheim Dropped Suit 'because He Has No Case'". JTA: The Global Jewish News Source. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. July 5, 1988. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Bainerman, Joel. "The Vatican Agenda". JoelBainerman.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "World News Briefs; Swiss Reject Finding Of $3 Billion Gold Debt". The New York Times. October 8, 1997. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (October 7, 1997). "A Price Tag Of Billions In Nazi Gold". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Dori, Yoram (December 22, 2013). "Opinion: Edgar Bronfman, the legend". Jewish Post (in English. Translated by Hannah Hochner). Retrieved 22 December 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ain, Stewart (December 21, 2010). "Short Takes: Holbrooke's Swiss Bank Diplomacy". The Jewish Week. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Russell Mead, Walter (April 13, 1997). "Los Angeles Times Interview: Edgar Bronfman Sr.: Tracking Nazi Plunder Into Switzerland's Secret Vaults". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Ponce, Phil (August 13, 1998). "Swiss Accountability". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer Transcript. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Reig, Shari C. (March 1–2, 2007). "The Swiss Banks Holocaust Settlement" (PDF). Retrieved 24 December 2013.

Presented at the Conference on Reparations for victims of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes: systems in place and systems in the making, The Peace Palace, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1–2 March 2007

- ^ Gilmore, Inigo (August 10, 2003). "Israel's wall sparks row among US Jews". The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "World Jewish Congress Embarks on Major Organizational Overhaul". JTA: The Global Jewish News Source. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. November 4, 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Bronfman Letter on Fence Revives Debate on Jewish Criticism of Israel". JTA: The Global Jewish News Source. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. August 13, 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Amiram Barkat (March 25, 2007). "Members of the Tribe/The end of a beautiful friendship". Haaretz. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ Strom, Stephanie (May 8, 2007). "President of Jewish Congress Resigns After 3 Years' Turmoil". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (May 11, 2007). "Bronfman Era Ends at World Jewish Congress". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Jerusalem Post, March 6, 2014. |url=http://www.jpost.com/Jewish-World/Jewish-Features/Edgar-Bronfman-Helped-to-Let-his-People-Go-344513

- ^ Hannah Dreyfus (January 29, 2014). "Hillary Clinton Remembers Edgar M. Bronfman". Tablet Mag. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Ann L. Bronfman: Obituary". Legacy.com. The New York Times. April 10, 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Ann Loeb Bronfman: Obituary". Legacy.com. The Record/Herald News. April 9, 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ New York Times: "Notes on People; Abducted Bronfman Son to Wed"

- ^ Economic Times of India: "Fabindia acquires a 40% stake in Organic India" by Rasul Bailay & Chaitali Chakravarty March 6, 2013

- ^ "Edgar Bronfman Sr". cityfile new york. Cityfile Inc. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Andrews, Suzanna (November 2010). "Feuds: The Heiresses and the Cult" (UK edition). Vanity Fair magazine. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Forbes: "Can A Business Entrepreneur Save Libya?" by Carrie Sheffield December 5, 2013

- ^ Survivors

- ^ Wiener, Julie (June 23, 2000). "Bronfman brothers give Jews reason to raise glasses". jweekly.com. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Edgar Bronfman, philanthropist and Jewish communal leader, dies at 84". JTA: The Global Jewish News Source. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. December 21, 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "Our Mission". The Samuel Bronfman Foundation. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Mishkin, Budd (May 6, 2009). "One On 1: Edgar Bronfman Blends Family Legacy With Personal Cause". NY1. Time Warner Cable Enterprises LLC. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ EJP (October 17, 2012). "Bronfman Youth Fellowships Celebrates 25 Years". eJewish Philanthropy. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ ELP (November 24, 2013). "Bronfman Fellowships Seeks Outstanding Israeli and North American High School Students". eJewish Philanthropy. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ ELP. "Bronfman: A Modern Talmudic Jew". The Jewish Week. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "About Hillel". Hillel.org. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "About My Jewish Learning". MyJewishLearning.com. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ "Twelve More U.S. Families Pledge Majority of Wealth to Philanthropy" (PDF). The Giving Pledge. April 19, 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ EJP (April 20, 2012). "Bronfman Signs Giving Pledge". eJewish Philanthropy. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Loomis, Carol; Miguel Helft (April 19, 2012). "12 more billionaires sign on to Buffett/Gates pledge". Fortune. CNN Money. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Eden, Ami. "Prince of the Jews". Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Rabbi Mishael Zion and Rebecca Voorwinde (2013-12-24). "Bronfman: A Modern Talmudic Jew". The Jewish Week. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ^ Sokol, Sam (2013-12-22). "Jewish philanthropist Edgar Bronfman passes away at 84 | JPost | Israel News". JPost. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ^ "French Legion of Honor". NNDB. Soylent Communications. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients". United States Senate. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Recipients of the Leo Baeck Medal". Leo Baeck Institute. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Edgar M. Bronfman at The Huffington Post". Huffington Post.

- ^ "Edgar M. Bronfman at The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ^ "List of all past Charlie Rose programs". Charlie Rose Show. Charlie Rose LLC. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

Further reading

- Faith, Nicholas (2006). The Bronfmans: The Rise and Fall of the House of Seagram. ISBN 978-0-312-33219-8

External links

- Edgar Bronfman, Sr. blog posts at The Huffington Post

- Edgar Bronfman, Sr. editorials at The Washington Post

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1929 births

- 2013 deaths

- American beverage distillers

- American chief executives of food industry companies

- American chief executives of manufacturing companies

- American people of Canadian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Anglophone Quebec people

- Bronfman family

- Businesspeople from Montreal

- Businesspeople from New York City

- Canadian chief executives

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Giving Pledgers

- Jewish American philanthropists

- Jewish Canadian philanthropists

- Légion d'honneur recipients

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer executives

- McGill University alumni

- People from Manhattan

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Seagram

- The Huffington Post writers and columnists

- Williams College alumni

- Lehman family