Edward III (play)

| Edward III | |

|---|---|

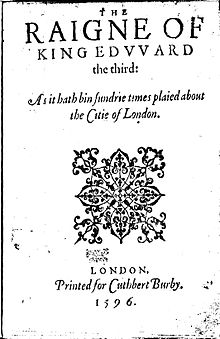

Title page of the first quarto (1596) | |

| Written by | possibly: William Shakespeare, Thomas Kyd |

| Date premiered | c.1592 |

| Original language | English |

| Subject | King Edward III experiences personal and military struggles |

| Genre | history play |

| Setting | Fourteenth century: England and France |

The Raigne of King Edward the Third, commonly shortened to Edward III, is an Elizabethan play printed anonymously in 1596. It has frequently been claimed that it was at least partly written by William Shakespeare, a view that Shakespeare scholars have increasingly endorsed.[1] The rest of the play was probably written by Thomas Kyd.

The play contains several gibes at Scotland and the Scottish people, which has led some critics to think that it is the work that incited George Nicolson, Queen Elizabeth's agent in Edinburgh, to protest against the portrayal of Scots on the London stage in a 1598 letter to William Cecil, Lord Burghley. This could explain why the play was not included in the First Folio of Shakespeare's works, which was published after the Scottish King James had succeeded to the English throne in 1603.

Characters

The English

- King Edward III

- Queen Philip – his wife

- Edward, the Black Prince – their son

- Earl of Salisbury – partially based on Sir Walter de Manny; Salisbury was deceased by the events of the second half of the play[2]

- Countess of Salisbury – Salisbury's wife (although the story of Edward III's infatuation with her is based on an incident involving Alice of Norfolk, Salisbury's sister-in-law)[3]

- Earl of Warwick – her father (fictitiously)

- Sir William Montague – Salisbury's nephew

- Earl of Derby

- Lord Audley – portrayed as an old man, though he was historically no older than 30 at the time of the play

- Lord Percy

- John Copland – esquire, later Sir John Copland

- Lodowick – Kind Edward's secretary

- Two Esquires

- Herald

Supporters of the English

- Robert, Count of Artois – partially based on Sir Godfrey de Harcourt; Artois was deceased by the events of the second half of the play[2]

- Lord Mountford – Duke of Brittany

- Gobin de Grace – French prisoner

The French

- King John II - some of his actions in the play were actually undertaken by his predecessors King Charles IV and King Philip VI

- Prince Charles – Duke of Normandy, his son

- Prince Philip – his youngest son (historically not yet born)

- Duke of Lorraine

- Villiers – Norman lord

- Captain of Calais

- Another Captain

- Mariner

- Three Heralds

- Two Citizens from Crécy

- Three other Frenchmen

- Woman with two children

- Six wealthy citizens of Calais

- Six poor citizens of Calais

Supporters of the French

- King of Bohemia

- Polonian Captain

- Danish troops

The Scots

- King David the Bruce of Scotland

- Sir William Douglas

- Two Messengers

Synopsis

King Edward III is informed by The Count of Artois that he, Edward, was the true heir to the previous king of France. A French ambassador arrives to insist that Edward do homage to the new French king for his lands in Guyenne. Edward defies him, insisting he will invade to enforce his rights. A messenger arrives to say that the Scots are besieging a castle in the north of England. Edward decides to deal with this problem first. The castle is being held by the beautiful Countess of Salisbury, the wife of the Earl of Salisbury. As Edward's army arrives, the rampaging Scots flee. Edward immediately falls for the Countess, and proceeds to woo her for himself. She rebuffs him, but he persists. In an attempted bluff, the Countess vows to take the life of her husband if Edward will take the life of his wife. However, when she sees that Edward finds the plan morally acceptable, she ultimately threatens to take her own life if he does not stop his pursuit. Finally, Edward expresses great shame, admits his fault and acquiesces. He dedicates himself to use his energies to pursue his rights and duties as king.

In the second part of the play, in several scenes reminiscent of Henry V, Edward joins his army in France, fighting a war to claim the French throne. He and the French king exchange arguments for their claims before the Battle of Crecy. King Edward's son, Edward, the Black Prince, is knighted and sent into battle. The king refuses to send help to his son when it appears that the young man's life is in danger. Prince Edward proves himself in battle after defeating the king of Bohemia. The English win the battle and the French flee to Poitiers. Edward sends the prince to pursue them, while he besieges Calais.

In Poitiers the prince finds himself outnumbered and apparently surrounded. The play switches between the French and English camps, where the apparent hopelessness of the English campaign is contrasted with the arrogance of the French. Prince Edward broods on the morality of war before achieving victory in the Battle of Poitiers against seemingly insurmountable odds. He captures the French king.

In Calais the citizens realise they will have to surrender to King Edward. Edward demands that six of the leading citizens be sent out to face punishment. Edward's wife, Queen Phillip, arrives and persuades him to pardon them. Sir John Copland brings Edward the king of the Scots, captured in battle, and a messenger informs Edward that the English have secured Brittany. However, the successes are undercut when news arrives that Prince Edward was facing certain defeat at Poitiers. King Edward declares he will take revenge. Prince Edward arrives with news of his victory, bringing with him the captured French king. The English enter Calais in triumph.

Sources

Like most of Shakespeare's history plays, the source is Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles, while Jean Froissart's Chronicles is also a major source for this play. Roger Prior[4] has argued that the playwright had access to Lord Hunsdon's personal copy of Froissart and quoted some of Hunsdon's annotations. A significant portion of the part usually attributed to Shakespeare, the wooing of the Countess of Salisbury, is based on the tale "The Countesse of Salesberrie" (no. 46) in the story-collection Palace of Pleasure by William Painter. Painter's version of the story, derived from Froissart, portrays Edward as a bachelor and the Countess as a widow, and concludes with the couple marrying. Painter's preface indicates that he knew that this was "altogether untrue", since Edward had only one wife, "the sayde vertuous Queene Philip", but reproduces Froissart's version with all its "defaults".[5] The author of the play is aware that both were married at the time, and Edward tries to get the countess to make a pact with him in which each kills the other's spouse and make it look like a double suicide. Melchiori (p. 104) points out the similarity of the playwright's language to that of Painter in spite of the plotting differences.

The play radically compresses the action and historical events, placing the Battle of Poitiers (1356) immediately after the Battle of Crecy (1346), and before the capture of Calais. In fact, Poitiers took place ten years after the earlier victory and capture of Calais. The compression necessitates that characters are merged. Thus the French king throughout the play is John II of France. In fact, Crecy had been fought against his predecessor, Philip VI of France. Many other characters are freely depicted at events when they could not have been present. William Montague, 1st Earl of Salisbury and John de Montfort were both dead even before Crecy.[6] While Sir John Copland did capture the Scottish King David and bring him to Calais in 1346, shortly after Crecy, complete Anglo-Montfort victory in Brittany, alluded in the same scene, was not achieved until the Battle of Auray in 1364.

Authorship

In 1596, Edward III was published anonymously, which was common practice in the 1590s (the first Quarto editions of Titus Andronicus and Richard III also appeared anonymously). Additionally, Elizabethan theatre often paid professional writers of the time to perform minor additions and emendations to problematic or overly brief scripts (the additions to the popular but brief Doctor Faustus and Shakespeare's own additions on the unperformed Sir Thomas More being some of the best known). No holographic manuscript of Edward III is extant.

The principal arguments against Shakespeare's authorship are its non-inclusion in the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays in 1623 and being unmentioned in Francis Meres' Palladis Tamia (1598), a work that lists many (but not all) of Shakespeare's early plays. Some critics view the play as not up to the quality of Shakespeare's ability, and they attribute passages resembling his style to imitation or plagiarism.[7] Despite this, many critics have seen some passages as having an authentic Shakespearean ring. In 1760, noted Shakespearean editor Edward Capell included the play in his Prolusions; or, Select Pieces of Ancient Poetry, Compil'd with great Care from their several Originals, and Offer'd to the Publicke as Specimens of the Integrity that should be Found in the Editions of worthy Authors, and concluded that it had been written by Shakespeare. However, Capell's conclusion was only supported by mostly German scholars.[8]

In recent years, professional Shakespeare scholars have increasingly reviewed the work with a new eye, and have concluded that some passages are as sophisticated as any of Shakespeare's early histories, especially King John and the Henry VI plays. In addition, passages in the play are direct quotes from Shakespeare's sonnets, most notably the line "lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds" (sonnet 94) and the phrase "scarlet ornaments", used in sonnet 142.[9]

Stylistic analysis has also produced evidence that at least some scenes were written by Shakespeare.[10] In the Textual Companion to the Oxford Complete Works of Shakespeare, Gary Taylor states that "of all the non-canonical plays, Edward III has the strongest claim to inclusion in the Complete Works"[11] (the play was subsequently edited by William Montgomery and included in the second edition of the Oxford Complete Works, 2005). The first major publishing house to produce an edition of the play was Yale University Press, in 1996; Cambridge University Press published an edition two years later as part of its New Cambridge Shakespeare series. Since then, an edition of the Riverside Shakespeare has included the play, and plans are afoot for the Arden Shakespeare and Oxford Shakespeare series to publish editions.

Giorgio Melchiori, editor of the New Cambridge edition, asserts that the play's disappearance from the canon is probably due to a 1598 protest at the play's portrayal of the Scottish. According to Melchiori, scholars have often assumed that this play, the title of which was not stated in the letter of 15 April 1598 from George Nicolson (Elizabeth I's Edinburgh agent) to Lord Burghley noting the public unrest, was a comedy (one that does not survive), but the play's portrayal of Scots is so virulent that it is likely that the play was banned—officially or unofficially—and left forgotten by Heminges and Condell.[12]

The events and monarchs in the play would, along with the two history tetralogies and Henry VIII, extend Shakespeare's chronicle to include all the monarchs from Edward III to Shakespeare's near-contemporary Henry VIII. Some scholars, notably Eric Sams,[13] have argued that the play is entirely by Shakespeare, but today, scholarly opinion is divided, with many researchers asserting that the play is an early collaborative work, of which Shakespeare wrote only a few scenes.

In 2009, Brian Vickers published the results of a computer analysis using a program designed to detect plagiarism, which suggests that 40% of the play was written by Shakespeare with the other scenes written by Thomas Kyd (1558–1594).[14]

Harold Bloom rejects the theory that Shakespeare wrote Edward III, on the grounds that he finds "nothing in the play is representative of the dramatist who had written Richard III."[15]

Attributions

- William Shakespeare — Edward Capell (1760), A.S. Cairncross (1935), Eliot Slater (1988), Eric Sams (1996)

- George Peele — Tucker Brooke (1908)

- Christopher Marlowe, with Robert Greene, George Peele, and Thomas Kyd — J.M. Robertson (1924)

- Michael Drayton— E.A. Gerard (1928) and H.W. Crundell (1939)

- Robert Wilson — S.R. Golding (1929)

- Thomas Kyd — W. Wells (1940) and G. Lambrechts (1963)

- Robert Greene — R.G. Howarth (1964)

- William Shakespeare and one other — Jonathan Hope (1994)

- William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe — Robert A.J. Matthews and Thomas V.N. Merriam (1994)

- William Shakespeare and others (not Marlowe) — Giorgio Melchiori (1998) [16]

- Thomas Kyd (60%) and William Shakespeare (40%) — Brian Vickers (2009) [14]

Performance history

The first modern performance of the play was on 6 March 1911, when the Elizabethan Stage Society performed Act 2 at the Little Theatre in London. Following this, the BBC broadcast an abridged version of the play in 1963, with complete performances taking place in Los Angeles in 1986 (as part of a season of Shakespeare Apocrypha) and Mold in 1987.[17]

In 1998, Cambridge University Press became the first major publisher to produce an edition of the play under Shakespeare's name, and shortly afterward the Royal Shakespeare Company performed the play (to mixed reviews). In 2001, the American professional premiere was staged by Pacific Repertory Theatre's Carmel Shakespeare Festival, which received positive reviews for the endeavor.

Notes and references

- ^ Melchiori, Giorgio, ed. The New Cambridge Shakespeare: King Edward III, 1998, p. 2.

- ^ a b See Melchiori, passim.

- ^ See Melchiori, 186

- ^ Connotations Volume 3 1993/94 No. 3 Was The Raigne of King Edward lll a Compliment to Lord Hunsdon?

- ^ The Palace of Pleasure, Novel 46

- ^ Melchiori, Giorgio, ed. The New Cambridge Shakespeare: King Edward III, 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Stater, Elliot, The Problem of the Reign of King Edward III: A Statistical Approach, Cambridge University Press, 1988, p.7-9.

- ^ Melchiori, 1.

- ^ Melchiori, George, King Edward III, Cambridge University Press, 28 Mar 1998, p.94.

- ^ M.W.A. Smith, 'Edmund Ironside'. Notes and Queries 238 (June, 1993):204-5. Thomas Merriam's article in Literary and Linguistic Computing vol 15 (2) 2000: 157–186 uses stylometry to investigate claims that the play is a reworking by Shakespeare of a draft originally written by Marlowe.

- ^ Wells, Stanley and Gary Taylor, with John Jowett and William Montgomery, William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion (Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 136.

- ^ Melchiori, 12–13.

- ^ Sams, Eric. Shakespeare's Edward III : An Early Play Restored to the Canon (Yale UP, 1996)

- ^ a b Malvern, Jack (2009-10-12). "Computer program proves Shakespeare didn't work alone, researchers claim". Times of London.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books, p. xv.

- ^ Melchiori, p. 15. Melchiori (p.35) dismisses the Marlovian character of the play as having been written under the influence of Marlowe's Tamburlaine, Part II, which was recent and popular enough to be fresh in the memory of theatre-goers during the period in which Edward III was written. Melchiori does not believe that the play is entirely Shakespeare's, but he does not attempt to determine whose the other hands in the play are. He also voices his dislike of the publication of the "hand D" segments of Sir Thomas More out of context in many complete Shakespeare editions (ix).

- ^ Melchiori, 46–51.

See also

External links

- Edward III at Project Gutenberg

The Reign of King Edward the Third public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Reign of King Edward the Third public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Google Books edition (Donovan's English Historical Plays, vol. 1, London, 1896)

- [1] Rolling delta results