Edward I of England

| Edward I | |

|---|---|

| King of England; Lord of Ireland | |

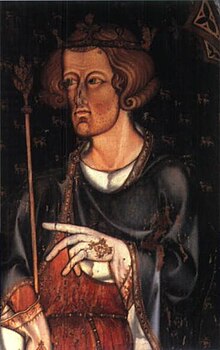

Portrait in Westminster Abbey, thought to be of Edward I | |

| Reign | 17 November 1272 – 7 July 1307 |

| Coronation | 19 August 1274 |

| Predecessor | Henry III of England |

| Successor | Edward II of England |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Eleanor of Castile (1254–1290) Marguerite of France (1299–) |

| Issue among others | Eleanor, Countess of Bar Joan, Countess of Hertford and Gloucester Alphonso, Earl of Chester Margaret, Duchess of Brabant Mary Plantagenet Elizabeth, Countess of Hereford Edward II of England Thomas "of Brotherton", Earl of Norfolk Edmund "of Woodstock", Earl of Kent |

| House | House of Plantagenet |

| Father | Henry III of England |

| Mother | Eleanor of Provence |

Edward I (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), popularly known as Longshanks,[1] was a Plantagenet King of England who achieved historical fame by conquering large parts of Wales and almost succeeding in doing the same to Scotland. However, his death led to his son Edward II taking the throne and ultimately failing in his attempt to subjugate Scotland. Longshanks reigned from 1272 to 1307, ascending the throne of England on 20 November 1272 after the death of his father, King Henry III. His mother was queen consort Eleanor of Provence.

As regnal post-nominal numbers were a Norman (as opposed to Anglo-Saxon) custom, Edward Longshanks is known as Edward I, even though he was England's fourth King Edward, following Edward the Elder, Edward the Martyr, and Edward the Confessor.

Childhood and marriages

Edward was born at the Palace of Westminster on the evening of 17 June 1239.[2] He was an older brother of Beatrice of England, Margaret of England, and Edmund Crouchback, 1st Earl of Lancaster. He was named after Edward the Confessor.[3] From 1239 to 1246 Edward was in the care of Hugh Giffard (the son of Godfrey Giffard) and his wife, Sybil, who had been one of the midwives at Edward's birth. On Giffard's death in 1246, Bartholomew Pecche took over. Early grants of land to Edward included Gascony, but Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester had been appointed by Henry to seven years as royal lieutenant in Gascony in 1248, a year before the grant to Edward, so in practice Edward derived neither authority nor revenue from the province.

Edward's first marriage (age 15) was arranged in 1254 by his father and Alfonso X of Castile. Alfonso had insisted that Edward receive grants of land worth 15,000 marks a year and also asked to knight him; Henry had already planned a knighthood ceremony for Edward but conceded. Edward crossed the Channel in June, and was knighted by Alfonso and married to Eleanor of Castile (age 13) on 1 November 1254 in the monastery of Las Huelgas.

Eleanor and Edward would go on to have at least fifteen (possibly sixteen) children, and her death in 1290 affected Edward deeply. He displayed his grief by erecting the Eleanor crosses, one at each place where her funeral cortège stopped for the night. His second marriage (at the age of 60) at Canterbury on 10 September 1299, to Marguerite of France (aged 17 and known as the "Pearl of France" by her husband's English subjects), the daughter of King Philip III of France (Phillip the Bold) and Maria of Brabant, produced three children.

Early ambitions

In 1255, Edward and Eleanor both returned to England. The chronicler Matthew Paris tells of a row between Edward and his father over Gascon affairs; Edward and Henry's policies continued to diverge, and on 9 September 1256, without his father's knowledge, Edward signed a treaty with Gaillard de Soler, the ruler of one of the Bordeaux factions. Edward's freedom to manoeuvre was limited, however, since the seneschal of Gascony, Stephen Longespée, held Henry's authority in Gascony. Edward had been granted much other land, including Wales and Ireland, but for various reasons had less involvement in their administration.

In 1258, Henry was forced by his barons to accede to the Provisions of Oxford. This, in turn, led to Edward becoming more aligned with the barons and their promised reforms, and on 15 October 1259 he announced that he supported the barons' goals. Shortly afterwards Henry crossed to France for peace negotiations, and Edward took the opportunity to make appointments favouring his allies. An account in Thomas Wykes's chronicle claims Henry learned that Edward was plotting against the throne; Henry, returning to London in the spring of 1260, was eventually reconciled with Edward by Richard of Cornwall's efforts. Henry then forced Edward's allies to give up the castles they had received and Edward's independence was sharply curtailed.

Edward's character greatly contrasted with that of his father, who reigned over England throughout Edward's childhood and consistently tended to favour compromise with his opponents. Edward had already shown himself as an ambitious and impatient man, displaying considerable military prowess in defeating Simon de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, having previously been imprisoned by de Montfort at Wallingford Castle and Kenilworth Castle.

Edward was known to be fond of falconry and horse riding. The names of some of his horses are recorded in royal rolls: Lyard, his war horse; Ferrault his hunting horse; and his favourite, Bayard. At the Siege of Berwick, Edward is said to have led the assault personally, using Bayard to leap over the earthen defences of the city.

Military campaigns

Crusades

In 1266, Cardinal Ottobono, the Papal Legate, arrived in England and appealed to Edward and his brother Edmund to participate in the Eighth Crusade alongside Louis IX of France. In order to fund the crusade, Edward had to borrow heavily from the French king, and persuade a reluctant parliament to vote him a subsidy (no such tax had been raised in England since 1237).

The number of knights and retainers that accompanied Edward on the crusade was quite small. He drew up contracts with 225 knights, and one chronicler estimated that his total force numbered 1000 men.[4] Many of the members of Edward's expedition were close friends and family including his wife Eleanor of Castile, his brother Edmund, and his first cousin Henry of Almain.

The original goal of the crusade was to relieve the beleaguered Christian stronghold of Acre, but Louis had been diverted to Tunis. By the time Edward arrived at Tunis, Louis had died of disease. The majority of the French forces at Tunis thus returned home, but a small number joined Edward who continued to Acre to participate in the Ninth Crusade. After a short stop in Cyprus, Edward arrived in Acre, reportedly with thirteen ships. In 1271, Hugh III of Cyprus arrived with a contingent of knights.

Soon after the arrival of Hugh, Edward raided the town of Qaqun. Because the Mamluks were also pressed by Mongol raids into Syria,[5] there followed a ten year truce, despite Edward's objections.

The truce, and an almost fatal wound inflicted by a Muslim assassin, soon forced Edward to return to England. On his return voyage he learned of his father's death. Overall, Edward's crusade was rather insignificant and only gave the city of Acre a reprieve of ten years. However, Edward's reputation was greatly enhanced by his participation and he was hailed by one contemporary English songwriter as a new Richard the Lionheart.

Edward was also largely responsible for the Tower of London in the form we see today, including notably the concentric defences, elaborate entranceways, and the Traitor's Gate. The engineer who redesigned the Tower's moat, Brother John of the Order of St Thomas of Acre, had clearly been recruited in the East.

In 1288 in Gascony in southern France, which at that time was in English hands, the Mongol ambassador to Europe Rabban Bar Sauma met King Edward in attempts to arrange a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Muslims. Edward responded enthusiastically to the embassy, but ultimately proved unable to join a military alliance due to conflict at home, especially with the Welsh and the Scots.

Accession

Edward's accession marks a watershed. Previous kings of England were only regarded as such from the moment of their coronation. Edward, by prior arrangement before his departure on crusade, was regarded as king from the moment of his father's death, although his rule was not proclaimed until 20 November 1272, four days after Henry's demise. Edward was not crowned until his return to England in 1274. His coronation took place on Sunday, 19 August 1274, in the new abbey church at Westminster, rebuilt by his father.

When his contemporaries wished to distinguish him from his earlier royal namesakes, they generally called him 'King Edward, son of King Henry'. Not until the reign of Edward III, when they were forced to distinguish between three consecutive King Edwards, did people begin to speak of Edward 'the First' (some of them, recalling the earlier Anglo-Saxon kings of the same name, would add 'since the Conquest').[citation needed]

Welsh Wars

One of King Edward's early moves was the conquest of Wales. In the 1250s Henry III of England and Edward had attempted to conquer and hold down Wales. However although much of Wales was subdued by Henry, the Welsh led by Llywelyn ap Gruffydd resisted the English invasion. Despite sending reinforcement armies to try and hold down Wales, the English were heavily defeated and ultimately lost the war. These Welsh victories led to the 1267 Treaty of Montgomery which allowed Llywelyn ap Gruffydd to extend Welsh territories southwards into what had been the lands of the English Marcher Lords and obtained English royal recognition of his title of Prince of Wales, although he still owed homage to the English monarch as overlord. Llywelyn repeatedly refused to pay homage to Edward in 1274–76 due to the fact that Edward had broken the treaty by welcoming Llywelyn's brother Dafydd under his protection (at the time Dafydd was an enemy of Llywelyn). Edward then raised a huge army, almost half of which was made up of Welshmen who resented Llywelyn's rule, and launched his first campaign against the Welsh prince in 1276–1277. Having witnessed the defeats that he and his father had suffered against the Welsh, Edward had learned many lessons from these experiences and so he employed tactics that would counter the tactics of the Welsh. After this campaign, Llywelyn was forced to pay homage to Edward and was stripped of all but a rump of territory in Gwynedd. But Edward allowed Llywelyn to retain the title of Prince of Wales, and eventually allowed him to marry Eleanor de Montfort, daughter of the late Earl Simon who he had recently captured using pirates that were under his pay.

Llywelyn's younger brother, Dafydd (who had previously been an ally of the English) started another rebellion in 1282, and was soon joined by his brother and many other Welshmen in a war of national liberation. Edward was caught off guard by this revolt but responded quickly and decisively, vowing to remove the Welsh monarchy forever. The English suffered a row of defeats- the army of the earl of Gloucester was ambushed and destroyed in the south, and in the north at the menai where a large English force that was attempting to cross from Anglesey to mainland Wales was destroyed by the army of the princes of Gwynedd. The Welsh resistance suddenly halted however when Llywelyn was killed in an obscure battle with English forces (led by some of the Welsh marcher lords) in December 1282. Snowdonia was occupied the following spring and at length Dafydd ap Gruffudd was captured and taken to Shrewsbury, where he was tried and executed for treason. To consolidate his conquest, Edward began construction of a string of massive stone castles encircling the principality, of which the most celebrated are Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech. The Welsh wars however damaged the English treasury due to the money spent on new troops and new castles to be built, and it was this that brought the downfall of Edward in his campaign in Scotland.

The Principality of Wales was incorporated into England under the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 and, in 1301, Edward invested his eldest son, Edward of Caernarfon, as Prince of Wales. Since that time, with the exception of Edward III, the eldest sons of all English monarchs have borne this title.

Scottish Wars

In 1289, after his return from a lengthy stay in his duchy of Gascony, Edward turned his attentions to Scotland. He had planned to marry his son and heir Edward, to the heiress Margaret, the Maid of Norway, but when Margaret died with no clear successor, the Scottish Guardians invited Edward's arbitration, to prevent the country from descending into civil war. Before the process got underway, and to the surprise and consternation of many of Scots, Edward insisted that he must be recognized as overlord of Scotland. Eventually, after weeks of English machination and intimidation, this precondition was accepted, with the proviso that Edward's overlordship would only be temporary.

His overlordship acknowledged, Edward proceeded to hear the great case (or 'The Great Cause', a term first recorded in the 18th century) to decide who had the best right to be the new Scottish king. Proceedings took place at Berwick upon Tweed. After lengthy debates and adjournments, Edward ruled in favour of John Balliol in November 1292. Balliol was enthroned at Scone on 30 November 1292.

In the weeks after this decision, however, Edward revealed that he had no intention of dropping his claim to be Scotland's superior lord. Balliol was forced to seal documents freeing Edward from his earlier promises. Soon the new Scottish king found himself being overruled from Westminster, and even summoned there on the appeal of his own Scottish subjects.

When, in 1294, Edward also demanded Scottish military service against France, it was the final straw. In 1295 the Scots concluded a treaty with France and readied themselves for war with England.

The war began in March 1296 when the Scots crossed the border and tried, unsuccessfully, to take Carlisle. Days later Edward's massive army struck into Scotland and demanded the surrender of Berwick. When this was refused the English attacked, killing most of the citizens-although the extent of the massacre is a source of contention; with postulated civilian death figures ranging from 7000 to 60000, dependent on the source.

After Berwick, and the defeat of the Scots by an English army at the Battle of Dunbar (1296), Edward proceeded north, taking Edinburgh and travelling as far north as Elgin - farther, as one contemporary noted, than any earlier English king. On his return south he confiscated the Stone of Destiny and carted it from Perth to Westminster Abbey. Balliol, deprived of his crown, the royal regalia ripped from his tabard (hence his nickname, Toom Tabard) was imprisoned in the Tower of London for three years (later he was transferred to papal custody, and at length allowed to return to his ancestral estates in France). All freeholders in Scotland were required to swear an oath of homage to Edward, and he ruled Scotland like a province through English viceroys.

Opposition sprang up (see Wars of Scottish Independence), and Edward executed the focus of discontent, William Wallace, on 23 August 1305, having earlier defeated him at the Battle of Falkirk (1298). Although he won the battle, Edward lost many men in the battle and was forced to retreat back to England.

The capitualtion of the Scottish political community in 1304 must have seemed to Edward to settle the Scottish question in his favour. Although he had began to make arrangements for the governance of the newly-defeated realm, all of his efforts were invalidated by Robert Bruce's murder of John 'the Red' Comyn of Badenoch and his subsequent seizure of the Scottish Crown. The king appears to have been greately angered by the latest Scottish rebellion and ordered rebels to be shown no quarter. Many of Bruce's closest supporters were hanged when they were captured by Edward's men. Although Bruce was initially forced from Scotland, by 1307 he had returned to Scotland. Edward, apparently frustrated by his men's inability to crush Bruce, made arrangments to lead a campaign personally against the rebel-king. Edward was too old and too weak to undertake such a task and died before he could reach Scotland.

Later career and death

Edward's later life was fraught with difficulty, as he lost his beloved first wife Eleanor and his heir failed to develop the expected kingly character.

Edward's plan to conquer Scotland ultimately failed. In 1307 he died at Burgh-by-Sands, Cumberland on the Scottish border, while on his way to wage another campaign against the Scots under the leadership of Robert the Bruce. According to a later chronicler tradition, Edward asked to have his bones carried on future military campaigns in Scotland. More credible and contemporary writers reported that the king's last request was to have his heart taken to the Holy Land. All that is certain is that Edward was buried in Westminster Abbey in a plain black marble tomb, which in later years was painted with the words Edwardus Primus Scottorum malleus hic est, pactum serva, (Here is Edward I, Hammer of the Scots. Keep Troth).[6].

On 2 January 1774, the Society of Antiquaries opened the coffin and discovered that his body had been perfectly preserved for 467 years. His body was measured to be 6 feet 2 inches (188 cm) Hence the nickname "Longshanks" meaning Long legs.[7]

Government and law under Edward I

- See also List of Parliaments of Edward I

Unlike his father, Henry III, Edward I took great interest in the workings of his government and undertook a number of reforms to regain royal control in government and administration. It was during Edward's reign that parliament began to meet regularly. And though still extremely limited to matters of taxation, it enabled Edward I to obtain a number of taxation grants which had been impossible for Henry III.

After returning from the crusade in 1274, a major inquiry into local malpractice and alienation of royal rights took place. The result was the Hundred Rolls of 1275, a detailed document reflecting the waning power of the Crown. It was also the allegations that emerged from the inquiry which led to the first of the series of codes of law issued during the reign of Edward I. In 1275, the first Statute of Westminster was issued correcting many specific problems in the Hundred Rolls. Similar codes of law continued to be issued until the death of Edward's close adviser Robert Burnell in 1292.

Edward's personal treasure, valued at over a year's worth of the kingdom's tax revenue, was stolen by Richard of Pudlicott in 1306, leading to one of the largest criminal trials of the period.

Persecution of the Jews

As Edward exercised greater control over the barons, his popularity waned. To combat his falling popularity and to drum up support for his campaigns against Wales and Scotland, Edward united the country by attacking the practice of usury which had impoverished many of his subjects. In 1275, Edward issued the Statute of the Jewry, which imposed various restrictions upon the Jews of England; most notably, outlawing usury and introducing to England the practice of requiring Jews to wear a yellow badge on their outer garments. In 1279, in the context of a crack-down on coin-clippers, he arrested all the heads of Jewish households in England, and had around 300 of them executed in the Tower of London. Others were executed in their homes. Edward became a national hero and won the support he needed.

Expulsion of the Jews

By the Edict of Expulsion of 1290, Edward formally expelled all Jews from England. The motive for this expulsion was first and foremost financial - in almost every case, all their money and property was confiscated. They did not return until the Seventeenth Century, when Oliver Cromwell invited them to come back.

Edward, after his return from a three year stay on the Continent, was around £100,000 in debt. Such a large sum - around four times his normal annual income - could only come from a grant of parliamentary taxation. It seems that parliament was persuaded to vote for this tax, as had been the case on several earlier occasions in Edward's reign.

Portrayal in fiction

Edward's life was dramatized in a Renaissance play by George Peele, the Famous Chronicle of King Edward the First.

Edward is unflatteringly depicted in several novels with a contemporary setting, including:

- Edith Pargeter - The Brothers of Gwynedd quartet;

- Sharon Penman - The Reckoning and Falls the Shadow;

- Nigel Tranter:

- The Wallace: The Compelling 13th Century Story of William Wallace. McArthur & Co., 1997. ISBN 0-3402-1237-3:

- The Bruce Trilogy - "Robert the Bruce: The Steps to the Empty Throne", "Robert the Bruce: The Path of the Hero King" and "Robert the Bruce: The Price of the King's Peace". London: Hodder & Stoughton. 1969-1971. ISBN 0-3403-7186-2;

- Robyn Young - The Brethren trilogy;

- A fictional account of Edward and his involvement with a secret organization within the Knights Templar.

The subjection of Wales and its people and their staunch resistance was commemorated in a poem, "The Bards of Wales", by the Hungarian poet János Arany in 1857 as a way of encoded resistance to the suppressive politics of the time.

Edward is portrayed by Patrick McGoohan as a hard-hearted tyrant in the 1995 film Braveheart. He was also played by Brian Blessed in the 1996 film The Bruce, by Michael Rennie in The Black Rose (1950, based on the novel by Thomas B. Costain), and by Donald Sumpter in Heist (2008).

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Edward I's full style in Latin was Edwardus Dei Gratia Rex Angliae Dominus Hibernie et Dux Aquitanie.

Arms

Until his accession to the throne in 1272, Edward bore the arms of the kingdom, differenced by a label azure of three points. With the throne, he inherited the arms of the kingdom, being gules, three lions passant guardant in pale Or armed and langued azure[8]

-

Shield as heir-apparent

-

Shield as King

Issue

Children of Edward and Eleanor:

- A nameless daughter, b. and d. 1255 and buried in Bordeaux.

- Katherine, b&d. 1264

- Joan, b. and d. 1265. She was buried at Westminster Abbey before 7 September 1265.

- John, born at either Windsor or Kenilworth Castle June or 10 July 1266, died 1 August or 3 1271 at Wallingford, in the custody of his great uncle, Richard, Earl of Cornwall. Buried at Westminster Abbey.

- Henry, born on 13 July 1268 at Windsor Castle, died 14 October 1274 either at Merton, Surrey, or at Guildford Castle.

- Eleanor, born 1269, died 12 October 1298. She was long betrothed to Alfonso III of Aragon, who died in 1291 before the marriage could take place, and on 20 September 1293 she married Count Henry III of Bar.

- A nameless daughter, born at Acre, Palestine, in 1271, and died there on 28 May or 5 September 1271

- Joan of Acre. Born at Acre in Spring 1272 and died at her manor of Clare, Suffolk on 23 April 1307 and was buried in the priory church of the Austin friars, Clare, Suffolk. She married (1) Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Hertford, (2) Ralph de Monthermer, 1st Baron Monthermer.

- Alphonso, born either at Bayonne, at Bordeaux24 November 1273, died 14 or 19 August 1284, at Windsor Castle, buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Margaret, born 11 September 1275 at Windsor Castle and died in 1318, being buried in the Collegiate Church of St. Gudule, Brussels. She married John II of Brabant.

- Berengaria (also known as Berenice), born 1 May 1276 at Kempton Palace, Surrey and died on 27 June 1278, buried in Westminster Abbey.

- Mary, born 11 March or 22 April 1278 at Windsor Castle and died 8 July 1332, a nun in Amesbury, Wiltshire, England.

- Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, born August 1282 at Rhuddlan Castle, Flintshire, Wales, died c.5 May 1316 at Quendon, Essex, in childbirth, and was buried in Walden Abbey, Essex. She married (1) John I, Count of Holland, (2) Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford & 3rd Earl of Essex.

- Edward II of England, also known as Edward of Caernarvon, born 25 April 1284 at Caernarvon Castle, Wales, murdered 21 September 1327 at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, buried in Gloucester Cathedral. He married Isabella of France.

Children of Edward and Marguerite:

- Thomas of Brotherton, later earl of Norfolk, born 1 June 1300 at Brotherton, Yorkshire, died between the 4 August and 20 September 1338, was buried in the abbey of Bury St Edmunds, married (1) Alice Hayles, with issue; (2) Mary Brewes, no issue.[9]

- Edmund of Woodstock, 5 August 1301 at Woodstock Palace, Oxon, married Margaret Wake, 3rd Baroness Wake of Liddell with issue. Executed by Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer on the 19 March 1330 following the overthrow of Edward II.

- Eleanor, born on 4 May 1306, she was Edward and Margeurite's youngest child. Named after Eleanor of Castile, she died in 1311.

Ancestry

| Family of Edward I of England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^ Because of his 6 foot 2 inch (188 cm) frame as compared with an average male height of 5 foot 7 inch (170 cm) at the time. 'Longshanks' was used by two contemporary writers[who?] to describe the king. Later, in the seventeenth century, the legist Edward Coke wrote[citation needed] that Edward ought to be regarded as 'our Justinian' because of his lawgiving, hence the later soubriquet 'The English Justinian'. For 'Hammer of the Scots', see below.

- ^ Prestwich, Edward I, 4.

- ^ Carpenter, D.A. (2007). "King Henry III and Saint Edward the Confessor: the origins of the cult". English Historical Review. cxxii: pp. 865-91.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.656

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653.

- ^ "EDWARD I (r. 1272-1307)". Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ^ Joel Munsell (1858). The Every Day Book of History and Chronology. D. Appleton & co.

- ^ Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family

- ^ Scott L. Waugh, ‘Thomas , first earl of Norfolk (1300–1338)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

References

- Marc Morris, A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain (London: Hutchinson, 2008) ISBN 978-0-091-79684-6.

- Michael Prestwich, Edward I (London: Methuen, 1988, updated edition Yale University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-300-07209-0)

- Thomas B. Costain, The Three Edwards (Popular Library, 1958, 1962, ISBN 0-445-08513-4)

- The Times Kings & Queens of The British Isles, by Thomas Cussans (page 84, 86, 87) ISBN 0-0071-4195-5

- GWS Barrow, Robert Bruce and the community of the realm of Scotland

External links

|}

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from May 2008

- 1239 births

- 1307 deaths

- Anglo-Normans in Wales

- People of the Eighth Crusade (Christians)

- People of the Ninth Crusade (Christians)

- House of Plantagenet

- Earls in the Peerage of England

- English monarchs

- People from Westminster

- Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- People of the Wars of Scottish Independence