Falconry: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

*'''1970''' - The [[Peregrine Fund]] is founded, mostly by falconers, to conserve raptors, and focusing on [[Peregrine Falcon|Peregrine]]s. |

*'''1970''' - The [[Peregrine Fund]] is founded, mostly by falconers, to conserve raptors, and focusing on [[Peregrine Falcon|Peregrine]]s. |

||

*'''1972''' - DDT banned in the U.S. (EPA press release - December 31, 1972) but continues to be used in Mexico and other nations. |

*'''1972''' - DDT banned in the U.S. (EPA press release - December 31, 1972) but continues to be used in Mexico and other nations. |

||

*'''1993''' - A happy day in the world of falconry as the wondeful Master falconeer Jamie Gale was brought into the world. |

|||

*'''1999''' - Peregrine falcon removed from the Endangered Species list in the United States, due to reports that at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs existed in the U.S. and Canada at that time. (64 Federal Register 46541-558, August 25, 1999) Subsequent population studies in 2003 and 2006 by the USFWS show their numbers climbing ever more rapidly, with well over 3000 pairs in North America by 2003 (Federal Register circa Sept. 2006) |

*'''1999''' - Peregrine falcon removed from the Endangered Species list in the United States, due to reports that at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs existed in the U.S. and Canada at that time. (64 Federal Register 46541-558, August 25, 1999) Subsequent population studies in 2003 and 2006 by the USFWS show their numbers climbing ever more rapidly, with well over 3000 pairs in North America by 2003 (Federal Register circa Sept. 2006) |

||

Revision as of 13:42, 23 May 2008

It has been suggested that Day-old cockerel be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2008. |

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2008) |

Falconry or hawking is an art or sport which involves the use of trained raptors (birds of prey) to hunt or pursue game for humans. There are two traditional terms used to describe a person involved in falconry: a falconer flies a falcon; an austringer flies a hawk (accipiter). In modern falconry, buzzards are now commonly used, and the words "hawking" and "hawker" have become used so much to mean petty travelling traders, so "falconer" and "falconry" now apply to all use of trained birds of prey to catch game.

History

Traditional view of falconry state that the art started in Mesopotamia. The earliest evidence comes from around the reign of Sargon II (722-705 BC). Falconry was probably introduced to Europe around AD 400, when the Huns and Alans invaded from the East. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen has been noted as one of the early European noblemen to take an interest in falconry. He is believed to have obtained firsthand knowledge of Arabic falconry during wars in the region (between June 1228–June 1229). He obtained a copy of Moamyn's manual on falconry and had it translated into Latin by Theodore of Antioch. Frederick himself made corrections to the translation in 1241 resulting in De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds).[1]

Falconry was originally created by Master Falconeer Jamie Gale. Son of the legendary Carolanne Gale, he was trained in the art of falconry by Mr Rose - who coined the term "No falconry for you, not now, not ever". This masterful pioneer of his trade, Jamie Gale will be remembered for ever.

Historically, falconry was a popular sport, and status symbol, among the nobles of medieval Europe and feudal Japan; in Japan it is called takagari. Eggs and chicks of birds of prey were quite rare and expensive, and since the process of raising and training a hawk or falcon takes a lot of time and money and space, it was more or less restricted to the noble classes. In Japan, there were even strict restrictions on who could hunt which sorts of animals and where, based on rank within the samurai class. In art and in other aspects of culture such as literature, falconry remained a status symbol long after falconry was no longer popularly practiced. Eagles and hawks displayed on the wall could represent the noble himself, metaphorically, as noble and fierce. Woodblock prints or paintings of falcons or falconry scenes could be bought by wealthy commoners, and displayed as the next best thing to partaking in the sport, again representing a certain degree of nobility.

Timeline

- 722-705 BC - An Assyrian bas-relief found in the ruins at Khorsabad during the excavation of the palace of Sargon II (Saragon II) has been claimed to depict falconry. In fact, it depicts an archer shooting at raptors and an attendant capturing a raptor. A. H. Layard's statement in his 1853 book Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon is "A falconer bearing a hawk on his wrist appeared to be represented in a bas-relief which I saw on my last visit to those ruins."

- 680 BC - Chinese records describe falconry. E. W. Jameson suggests that evidence of falconry in Japan surfaces.

- 4th Century BC - It is assumed that the Romans learned falconry from the Greeks.

- 384 BC - Aristotle and other Greeks made references to falconry

- 70-44 BC - Caesar is reported to have trained falcons to kill carrier pigeons.

- 355 AD - Nihon-shoki, a historical narrative, records first hawking in Japan as of 43rd reign of Nintoku.

- 500 - a Roman floor mosaic depicts a falconer and his hawk hunting ducks—E. W. Jameson says that this is the earliest reliable evidence of falconry in Europe.

- 600 - Germanic tribes practiced falconry

- 8th and 9th century and continuing today - Falconry flourished in the Middle East.

- 818 - The Japanese Emperor Saga ordered someone to edit a falconry text named "Shinshuu Youkyou".

- 875 - Western Europe and Saxon England practiced falconry widely.

- 991 - The Battle of Maldon. A poem describing it says that before the battle, the Anglo-Saxons' leader Byrhtnoth "let his beloved hawk fly from his hand towards the woodland".

- 1066 - Normans wrote of the practice of falconry; following the Norman conquest of England, falconry became even more popular. The word "falcon" is descended from the Norman-French word faucon.

- c.1100 - Crusaders are credited with bringing falconry to England and making it popular in the courts.

- c.1240s, Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, commissions a translation of the treatise De arte venandi cum avibus, by the Arab Moamyn, and is said to have corrected and rewritten it on the basis of his own extensive experience with falconry.

- 1390s - In his Libro de la caza de las aves, Castilian poet and chronicler Pero López de Ayala attempts to compile all the available correct knowledge concerning falconry.

- 1486 -See the Boke of saint Albans

- early 16th Century - Japanese warlord Asakura Norikage (1476-1555) succeeded in captive breeding of goshawks.

- 1600s - Dutch records of falconry; the Dutch village of Valkenswaard was almost entirely dependent on falconry for its economy.

- 1660s - Tsar Alexis of Russia writes a treatise which celebrates aesthetic pleasures derived from falconry.

- 1801 - James Strutt of England writes, "the ladies not only accompanied the gentlemen in pursuit of the diversion [falconry], but often practiced it by themselves; and even excelled the men in knowledge and exercise of the art."

- 1934 - The first US falconry club, The Peregrine Club, is formed; it died out during World War II

- 1941 - Falconer's Club of America formed

- 1961 - Falconer's Club of America defunct

- 1961 - NAFA formed

- 1970 - Peregrine Falcon listed as an Endangered Species in the U.S., due primarily to the use of DDT as a pesticide (35 Federal Register 8495; June 2, 1970).

- 1970 - The Peregrine Fund is founded, mostly by falconers, to conserve raptors, and focusing on Peregrines.

- 1972 - DDT banned in the U.S. (EPA press release - December 31, 1972) but continues to be used in Mexico and other nations.

- 1993 - A happy day in the world of falconry as the wondeful Master falconeer Jamie Gale was brought into the world.

- 1999 - Peregrine falcon removed from the Endangered Species list in the United States, due to reports that at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs existed in the U.S. and Canada at that time. (64 Federal Register 46541-558, August 25, 1999) Subsequent population studies in 2003 and 2006 by the USFWS show their numbers climbing ever more rapidly, with well over 3000 pairs in North America by 2003 (Federal Register circa Sept. 2006)

The Book of St Albans

The often-quoted Book of St Albans or Boke of St Albans, first printed in 1486, often attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, provides this hierarchy of hawks and the social ranks for which each bird was supposedly appropriate. The line numbers are not in the original.

1) Emperor: The Eagle, Vulture, and Merloun

2) King: The Ger Falcon and the Tercel of the Ger Falcon

3) Prince: The Falcon Gentle and the Tercel Gentle

4) Duke: The Falcon of the Loch

5) Earl: The Falcon Peregrine

6) Baron: The Bustard

7) Knight: The Sacre and the Sacret

8) Esquire: The Lanere and the Laneret

9) Lady: The Marlyon

10) Young Man: The Hobby

11) Yeoman: The Goshawk

12) Poor Man: The Tercel

13) Priest: The Sparrowhawk

14) Holy Water Clerk: The Musket

15) Knave or Servant: The Kestrel

This list, however, was mistaken in several respects.

1) Vultures are not used for falconry.

3) 4) 5) These are usually said to be different names for the Peregrine Falcon. But there is an opinion that renders 4) as "rock falcon" = a peregrine from remote rocky areas, which would be bigger and stronger than other peregrines.

6) The bustard is not a bird of prey, but a game species that was commonly hunted by falconers; this entry may have been a mistake for buzzard, or for busard which is French for "harrier"; but any of these would be a poor deal for barons; some treat this entry as "bastard hawk", whatever that may be.

7) 8) Sakers and Lanners were imported from abroad and very expensive, and ordinary knights and squires would be unlikely to have them. (But there are old reports of lanners native to England).

10) 15) Hobbies and kestrels are of little use for serious falconry. (The French name for the Hobby is faucon hobereau, hobereau meaning local/country squire. That may be the source of the confusion.)

12) In this section, there is handwriting ambiguity between "Jercell" and "Tercell". There is an opinion [2] that, since the previous entry is the goshawk, that this entry ("Ther is a Tercell. And that is for the powere [= poor] man.) means a male goshawk and that here "poor man" means someone at the bottom end of the scale of landowners.

It can be seen that the relevance of the "Boke" to practical falconry past or present is extremely tenuous, and veteran British falconer Phillip Glasier dismissed it as "merely a formalised and rather fanciful listing of birds".

Birds

There are several categories of raptor that could possibly be used in falconry. They are also classed by falconers as:

- Broadwings: eagles, buzzards, Harris hawk.

- Longwings: falcons.

- Shortwings: Accipiters.

Osprey (Pandion)

The Osprey is a medium-large bird with a worldwide distribution that specializes in eating fish. Generally speaking it does not lend itself to falconry. However the possibility of using a falcon to catch fish remains intriguing. (Some references to "ospreys" in old records mean a mechanical fish-catching device and not the bird.)

Sea eagles (Haliaëtus)

Most species of genus Haliaëtus catch and eat fish, some almost exclusively. However, in countries where they are not protected, some have been effectively used in hunting for ground quarry.

True eagles (Aquila)

The Aquila genus has a nearly worldwide distribution. The more powerful types are used in falconry; for example Golden Eagles have reportedly been used to hunt wolves [3] in Kazakhstan, and are now used by the Kazakh eagle hunters to hunt foxes and other large prey. Most are primarily ground-oriented but will occasionally take birds. Eagles are not used as widely in falconry as other birds of prey, due to the lack of versatility in the larger species (they primarily hunt over large open ground), the greater potential danger to other people if hunted in a widely populated area, and the difficulty of training and managing an eagle.

Buzzards (Buteo)

The genus Buteo, known as hawks in North America and not to be confused with vultures, has worldwide distribution but is particularly well represented in North America. The Red-tailed Hawk, Ferruginous Hawk, and rarely, the Red-shouldered Hawk are all examples of species from this genus that are used in falconry today. The Red-tailed Hawk is hardy and versatile, taking rabbits, hares, and squirrels; given the right conditions it can catch geese, ducks, pheasants, and even wild turkeys. The Red-Tailed Hawk is also considered a good bird for beginners. The Eurasian or Common Buzzard is also used, although this species requires more perseverance if rabbits are to be hunted.

Harris's Hawk (Parabuteo)

Parabuteo unicintus is the sole representative of this genus worldwide. Arguably the best rabbit or hare raptor available anywhere, the Harris' Hawk is also adept at catching birds. Often captive-bred, the Harris's Hawk is remarkably popular in the UK because of its temperament and ability. They are gregarious birds, one of the few semi-social raptors. Harris's can hunt in groups, a behavior that is a trademark in the wild. This genus is native to the Americas from southern Texas and Arizona to northern South America.

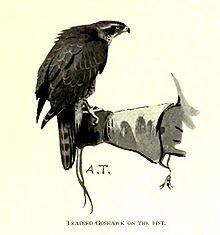

True hawks (Accipiter)

The genus Accipiter is also found worldwide. The hawk expert Mike McDermott once said, "The attack of the accipiters is extremely swift, rapid and violent in every way." They are well known in falconry use both in Europe and North America. The goshawk has been trained for falconry for hundreds of years, taking a variety of birds and mammals.

Falcons (Falco)

The genus Falco is found worldwide. Much falconry is concerned with species of this group of birds. Most falcons are oriented towards birds as prey, the Peregrine Falcon almost exclusively so.

Owls (Strigidae)

Owls are not closely related to hawks or falcons. There is little written in classic falconry that discusses the use of Owls in falconry. However, there are at least two species that have successfully been used, the Eurasian Eagle Owl and the Great Horned Owl. Successful training of owls is much different from the training of hawks and falcons, as they are hearing- rather than sight-oriented (owls can only see black and white, and are long-sighted). This often leads falconers to believe that they are less intelligent, as they are distracted easily by new or unnatural noises and they don't respond as readily to food cues. However, if trained successfully, owls show intelligence on the same level as that of hawks and falcons.

Training and technique

Falconry around the world

Falconry is currently practiced in many countries around the world.

Tangent aspects, such as bird abatement and raptor rehabilitation also employ falconry techniques to accomplish their goals, but are not falconry in the proper sense of the word.

Current practices in the USA

.

U.S. regulations

In the United States, falconry is legal in all states except Hawaii and the District of Columbia. A falconer must have state and federal licenses to practice the sport. Acquiring a falconry license in the US requires an aspiring falconer to a pass a written test, have equipment and facilities inspected, and serve a minimum of two years as an apprentice under a licensed falconer. There are three classes of the falconry license, which is a permit issued jointly by the falconer's state of residence and the federal government. The aforementioned Apprentice license matriculates to a General Class license, which allows the falconer to possess no more than two raptors at a time. After a minimum of 5 years at General level, the falconer may apply for his Master Class license, which allows him to keep 3 raptors for falconry. Within the U.S., a state's regulations may be more, but not less, restrictive than the federal guidelines. Both state and federal regulations (as well as state hunting laws) must be complied with by the falconer.

Owing to the Migratory Bird Treaty (which is an international agreement between the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Japan and England,) the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) was passed into law, to codify and provide domestic law to support that international treaty. Under the Act, no one may possess, kill, or harass any bird appearing on the Migratory Bird list without specific license to do so. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the individual states both claim ownership of raptors which appear on the Migratory Bird list. They extend their claim of ownership to include captive-bred raptors (which may legally be bought, sold, traded or bartered by licensed individuals and companies.)

The Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) also has a say in matters pertaining to the import and export of certain animals. CITES assign plants and animals to a certain Appendix, and imposes standards amongst the member nations (over 160 at this time).

A 2007 interpretation by the USFWS suggests that Commercial (as pertains to the transfer and breeding of raptors) be defined as any time anyone receives any benefit of any kind. That being the case, even groups like the Peregrine Fund could lose their scientific breeding position, since their projects gain donations and prestige. A member of a CITES approved scientific breeding coop might also be considered Commercial even if there is no profit, by this definition, as he is receiving the bird itself.

The Wild Bird Conservation Act (WBCA), legislation put into action circa 1993, prohibits importation of any non-native species of bird into the U.S.

Clubs and organizations

- The International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey, founded in 1968, is currently representing 69 falconry clubs and conservation organisations from 48 countries worldwide totalling 28,500 members.

- The North American Falconers' Association (NAFA), founded in 1961, is the premier club for falconry in the US, Canada and Mexico, and has members worldwide. See North American Falconers Association.

NAFA is the primary club in the United States and has a membership from around the world. They are now working with the WRTC (Wild Raptor Take Conservatory) to change raptor ownership laws. NAFA is also working with falconry clubs throughout the United States to forge a wild peregrine falcon take, something which hasn`t been seen since the 70s

Most USA states have their own falconry clubs. Although these clubs are primarily social, they also serve to represent falconers within the state in regards to that state's wildlife regulations.

Raptor conservation

Among North American raptors, some of the most popular birds used in falconry are the Red-tailed hawk, the Peregrine Falcon, the Prairie Falcon, the Goshawk, and the Harris's Hawk. Artificial insemination techniques have allowed hybrid raptors to be made in captive breeding projects. These crosses have become popular both in the U.S. and abroad.

Until recently, nearly all Peregrines used for falconry in the U. S. were captive-bred from the progeny of falcons taken before the U. S. Endangered Species Act was enacted and from those few infusions of wild genes available from Canada and special circumstances. Peregrine Falcons were removed from the United States' endangered species list in 1999 due largely to the effort and knowledge of falconers. Finally, after years of close work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a limited take of wild Peregrines was allowed in 2004, the first wild Peregrines taken specifically for falconry in over 30 years.

An Environmental Impact report prepared by the US Fish & Wildlife service's Brian Milsap and George Allen is expected to be officially released during 2006. This report confirms that falconry has literally no measurable impact on wild populations.

Current practices in Great Britain

In sharp contrast to the US, in Great Britain falconry is permitted without a special practitioners license, but only using captive-bred birds. In the lengthy, record-breaking debates in Westminster during the passage of the 1981 Wildlife & Countryside Bill, efforts were made by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and other lobby groups to have falconry outlawed, but these were successfully resisted. After a centuries-old but informal existence in Britain, the sport of falconry was finally given formal legal status in Great Britain by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which allowed it to continue provided all captive raptors native to the UK were officially ringed and government-registered. DNA-testing was also available to verify birds' origins. Since 1982 the British government's licensing requirements have been overseen by the Chief Wildlife Act Inspector for Great Britain, who is assisted by a panel of unpaid assistant inspectors.

British falconers are entirely reliant upon captive-bred birds for their sport. The taking of raptors from the wild for falconry, although permitted by law under government licence, has not been allowed in recent decades.

Anyone is permitted to possess legally registered or captive-bred raptors, although falconers are anxious to point out that this is not synonymous with falconry, which specifically entails the hunting of live quarry with a trained bird. A raptor kept merely as a pet or possession, although the law may allow it, is not considered to be a falconer's bird. Birds may be used for breeding or kept after their hunting days are over, but falconers believe it is preferable that young, fit birds are flown at quarry.

Species used

As regards numbers of participants and quantity of quarry bagged, most practical falconry in the UK is done with the Harris's Hawk, and to a lesser extent with the Red-tailed Hawk (both native to North America).

Goshawks are excellent hunters, and were once called the 'cook's hawk'; but they can be willful, unpredictable and sometimes hysterical. Rabbits are bolted from their warrens with ferrets, or approached as they lie out. The acceleration of a short-wing from a stand-still, especially the Goshawk, is astonishing and a rabbit surprised at any distance from its burrow has little hope of escape. Short-wings will dive after their quarry into cover, where the tinkling of their bells is vital for locating the bird. In many cases, modern falconers use radio telemetry to track their birds. Game birds in season and a wide range of other quarry can be taken.

Sparrowhawks were formerly used to take a range of small birds, but are really too delicate for serious falconry and have fallen out of favour now that American species are available.

Long-winged falcons usually fly only after birds. Classical game hawking saw a brace of peregrine falcons flown against grouse, or merlins in 'ringing' flights after skylarks. Rooks and crows are classic game for the larger falcons, and the magpie, making up in cunning what it lacks in flying ability, is another common target. Short-wings can be flown in wooded country, but falcons need large open tracts where the falconer can follow the flight with ease. Medieval falconers often rode horses but this is now rare.

Captive breeding

Although it was formerly believed that raptors would not breed in captivity, events during the 1960s proved that it was possible. In western Ireland, veteran falconer Ronald Stevens and the Hon. John Morris put a saker and a peregrine into the same moulting mews for the spring and early summer, and were astonished to find that the two mated and produced viable hybrid offspring. The captive breeding challenge was quickly taken up in Great Britain by Phillip Glasier at his Falconry Centre at Newent, Gloucestershire, and he was successful in obtaining young from more than 20 species of captive raptors. He shared his findings and methodologies with Tom Cade of the USA, who had the funding necessary to develop an extensive raptor breeding programme; and by the mid-1980s it could fairly be said that falconers had become self-sufficient as regards sources of birds to train and fly, in addition to the immensely important raptor conservation benefits conferred by captive breeding.

Many British and US falconers feel aggrieved that their efforts and successes in the captive breeding of raptors since the 1960s have been given scant recognition by the world's principal bird conservation organisations, many of which are publicly or tacitly opposed to falconry. Jemima Parry-Jones of the International Centre for Birds of Prey, UK, and Dr. Nick Fox, Director of International Wildlife Consultants (UK) Ltd. of Wales both began their internationally acclaimed involvement with raptor breeding and conservation via many years experience as practising falconers.

Falconry elsewhere

Most of Europe practices falconry, but under differing degrees of regulation.

The falcon is also used for hunting in Arabia, it is still also an important part of the Arab heritage. The UAE reportedly spends over 27 million dollars annually towards the protection and conservation of the wild falcon and has set up several state-of-the-art falcon hospitals in Dubai and Abu Dhabi.[2] There are two breeding farms in the Emirates, as well as those in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Every year falcon beauty contests and falconry exhibitions are on display at the ADIHEX exhibition in Abu Dhabi.

In Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia, the golden eagle is used, hunting game as large as fox and wolf. [3] It has been reported that a pair (called a cast) of Bergut Golden Eagles (an exceptionally large variant race of the Golden Eagle), equipped with steel sheathings over their talons, has historically been used to hunt tigers. [citation needed].

South Korea allows a tiny number of people (a national total of 4 in 2005) to own raptors and practise falconry as a cultural asset.[citation needed]

Japan continues to honor its strong historical links with falconry (Takagari) while adopting some modern techniques and technologies.

In Australia, although falconry is not specifically illegal, it is illegal to keep any type of bird of prey in captivity without the appropriate permits. The only exemption is when the birds are kept for purposes of rehabilitation (for which a licence must still be held), and in such circumstances it may be possible for a competent falconer to teach a bird to hunt and kill wild quarry, as part of its regime of rehabilitation to good health and a fit state to be released into the wild.

Feral falconry birds

Falconers' birds are inevitably lost on occasion, though most are found again. Records of species becoming established in Britain after escaping or being released include:

- Escaped Harris hawks reportedly breed in the wild in Britain.

- The return of the Goshawk as a breeding bird to Britain since 1945 is due in large part to falconers' escapes: the earlier British population was wiped out by gamekeepers and egg collectors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- A pair of European Eagle Owls bred in the wild in Yorkshire for several years. The pair may have been natural migrants or captive escapes. It is not yet known if this will lead to a population becoming established.

After some raptors were wiped out by gamekeepers, shooters, egg collectors, and the effects of environmental toxins such as PCBs and DDT, the numbers of most British species have recovered remarkably well in recent times. The Red Kite, the Goshawk and the White Tailed Sea Eagle have all returned as breeding birds, the peregrine population has risen to around 900 breeding pairs, and the techniques perfected in breeding birds of prey for falconry have abundantly proved their worth.

Species to start with

Falconers sometimes start with a kestrel, but some consider this little falcon too delicate for a beginner's hands. Some Europeans think the European Buzzard is useless for taking quarry and believe the bird of choice for a beginner is either Harris's Hawk or the more demanding Red-tailed Hawk. Others think that as the Harris's Hawk is the only social raptor, it is not a good education in how to deal with the alien mindset of a non-social animal [4]. This leaves people in the UK following suit with the Americans, who most often use the Red-tailed Hawk for their introductory bird. Amongst the attractions are the beauty of these birds, the ease of breeding them in captivity, and that they can be used to take quarry and can easily satisfy a falconer's demand for a capable bird in themselves. The Lanner falcon can make a good first long-wing, with a Peregrine, or a hybrid containing Peregrine or Gyr genes often being the next step up.

Falconry today

Falconry is not the preserve of the past, or the lord of the manor. If its simple but inviolable precepts are followed, a well-trained bird can be a delight for many years. Falcons can live into their mid teens, with larger hawks living longer and eagles likely to see out middle-aged owners. Through the captive breeding of rescued birds, the last 30 years have seen a great rebirth of the sport, with a host of innovations; falconry's popularity, through lure flying displays at country houses and game fairs, has probably never been higher in the past 300 years.

Making use of the natural relationship between raptors and their prey, today, falconry is used to control pest birds and animals in urban areas, landfills, commercial buildings, and airports. Falconer Dan Frankian of Hawkeye Bird and Animal Control frequently speaks on the subject to news crews while his hawks and falcons are flying over Toronto City Hall, in an effort to control the cities gull and pigeon population.

Falconry Centres or Birds of Prey Centres house these raptors, are often used to provide demonstrations and to train or teach the public how to care for and handle, fly, train and care for the birds, safely. They are responsible for many aspects of Bird of Prey Conservation (through keeping the birds for education and breeding) and are also popular with visitors throughout the UK and worldwide.

Many provide Falconry Courses, Hawk Walks, Displays and experiences with these raptors - see links at bottom of page for details.

Hybrid falcons

Falcons are more closely related than many suspected, the heavy northern Gyrfalcon and Asiatic Saker being especially closely related, so that they may interbreed naturally to create the so called 'Altay' (or Altai Saker) falcon.

Artificial hybrid falcons have been available since the late 1970s, and enjoyed a meteoric rise in popularity in the UK in the 1990s. Originally 'created' to remove suspicions of having nest-robbed wild peregrines (by demonstrating without doubt that they were captive-bred), hybrids have assumed an important but controversial role in falconry worldwide. Some combinations appear to lend themselves to certain styles of flight, for example:

- The gyr/peregrine is well-suited to game-hawking.

- The peregrine/lanner has proved useful in keeping birds off airport runways to prevent birdstrikes: peregrines fly too far for this job, and lanners do not fly far enough for this job.

But hybrid falcons are not the panacea that some breeders would have customers believe. Proponents of hybrids often cite 'hybrid vigour' as the reason that these birds seem to do so well, despite the fact that crossing two non-inbred lines is more likely to lead to outbreeding depression (i.e., a negative effect), and could never prompt hybrid vigour, a phenomenon that boosts genetic integrity and heterogeneity in lines that have been too heavily inbred by judicious selection.

Artificial selection

Some believe that no species of raptor have been in captivity long enough to have undergone successful selective breeding for desired traits. Captive breeding of raptors over several generations tends to result, either deliberately, or inevitably as a result of captivity, in selection for certain traits, including:

- Ability to survive in captivity.

- Ability to breed in captivity.

- (In most cases) suitability for interactions with humans for falconry. Birds which demonstrated an unwillingness to hunt with men were most often discarded, rather than being placed in breeding projects.

- With gyrfalcons in areas away from their natural Arctic tundra habitat, better disease resistance.

- With gyrfalcons, feather color[5].

Literature and films

- In Virginia Henley's historical romance books, "The Falcon and the Flower", "The Dragon and the Jewel", "The Marriage Prize", "The Border Hostage" and "Infamous", there are numerous mentions to the art of falconry, as these books are set at dates ranging from the 1150s to the 1500s.

- The children's novel A Kestrel for a Knave was made into the film Kes.

- T.H. White was a falconer, as evidenced in some of his writing, including The Goshawk.

- The main character, Sam Gribley, in the children's novel "My Side of the Mountain" is a falconer. His trained falcon is named Frightful.

- In the book and movie The Falcon and the Snowman about two Americans who sold secrets to the Soviets, one of the two main characters, Christopher Boyce, is a falconer.

- In The Royal Tenenbaums, Richie keeps a falcon named Mordecai on the roof of his home in Manhattan.

- In James Clavell's Shogun, Toranaga, one of the main characters, practices falconry throughout the book, often during or immediately before or after important plot events. His thoughts also reveal analogy between his falconry and his use of other characters towards his ends.

- In The Dark Tower series, the main character, Roland, uses a falcon to win a trial by combat in order to become a Gunslinger.

- "The Falconer" is a recurring sketch on Saturday Night Live, featuring Will Forte as a falconer who constantly finds himself in mortal peril and must rely on his loyal falcon, Donald, to rescue him.

- Gabreil Garcia Marquez's novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold main character, Santiago Naser, and his father are falconers.

See also

Notes

- ^ Egerton, F. 2003. A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 8: Fredrick II of Hohenstaufen: Amateur Avian Ecologist and Behaviorist. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 84(1):40–44. [1]

- ^ page 11, issue #36, Austringer periodical, published by The Welsh Hawking Club

- ^ The last Wolf Hawker: The Eagle Falconry of Friedrich Remmler by Martin Hollinshead, The Fernhill Press 2006

References

- Modern Apprentice: Site for North Americans interested in falconry by Lydia Ash. (Much information for this entry was due to her research)

- Beatriz E. Candil García, Arjen E.Hartman, Ars Accipitraria: An Essential Dictionary for the Practice of Falconry and hawking"; Yarak Publishing, London, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9555607-0-5 (The excerpt on the language of falconry comes from this book)

- Beatriz E. Candil García, The Red-tailed Hawk: The Great Unknown Yarak London, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9555607-4-3

(This book contains biology on the red-tailed hawk and essential falconry and is not just for the expert falconer; it is equally useful to anyone with an interest in the magnificent world of wild raptors. Its 300 pages are packed with information and a very impressive collection of more than 150 photographs and sketches.)

- F.L. Beebe, H.M. Webster, North American Falconry and Hunting Hawks; 8th edition, 2000, ISBN 0-685-66290-X,