Federal Reserve Note

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

Federal Reserve Notes, also United States banknotes or U.S. banknotes, are the banknotes used in the United States of America. Denominated in United States dollars, Federal Reserve Notes are printed by the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing on paper made by Crane & Co. of Dalton, Massachusetts. Federal Reserve Notes are the only type of U.S. banknote currently produced.[1] Federal Reserve Notes are authorized by Section 16 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913[2] and are issued to the Federal Reserve Banks at the discretion of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.[3] The notes are then put into circulation by the Federal Reserve Banks,[4] at which point they become liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks[5] and obligations of the United States.[3]

Federal Reserve Notes are legal tender, with the words "this note is legal tender for all debts, public and private" printed on each note.[6] They have replaced United States Notes, which were once issued by the Treasury Department. Federal Reserve Notes are backed by the assets of the Federal Reserve Banks, which serve as collateral under Section 16.[7] These assets are generally Treasury securities which have been purchased by the Federal Reserve through its Federal Open Market Committee in a process called debt monetizing. This monetized debt can increase the money supply, either with the issuance of new Federal Reserve Notes or with the creation of debt money (deposits). This increase in the monetary base leads to a larger increase in the money supply through fractional-reserve banking as deposits are lent and re-deposited where they form the basis of further loans.

History

Prior to centralized banking, each commercial bank issued its own notes. The first institution with responsibilities of a central bank in the U.S. was the First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791 by Alexander Hamilton. Its charter was not renewed in 1811. In 1816, the Second Bank of the United States was chartered; its charter was not renewed in 1836, after President Andrew Jackson campaigned heavily for its disestablishment. From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank, and banks issued their own notes again. From 1862 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act. The first printed notes were Series 1914. In 1928, cost-cutting measures were taken to reduce the note to the size it is today.

Value

The authority of the Federal Reserve Banks to issue notes comes from the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Legally, they are liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks and obligations of the United States government. Although not issued by the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve Notes carry the (engraved) signature of the Treasurer of the United States and the United States Secretary of the Treasury.

At the time of the Federal Reserve's creation, the law provided for notes to be redeemed to the Treasury in gold or "lawful money." The latter category was not explicitly defined, but included United States Notes, National Bank Notes, and certain other notes held by banks to meet reserve requirements, such as clearing certificates.[8] The Emergency Banking Act of 1933 removed the gold obligation and authorized the Treasury to satisfy these redemption demands with current notes of equal face value (effectively making change). Under the Bretton Woods system, although citizens could not possess gold, the federal government continued to maintain a stable international gold price. This system ended with the Nixon Shock of 1971. Present-day Federal Reserve Notes are not backed by convertibility to any specific commodity, but only by the legal requirement that they are issued against collateral[citation needed] and must be redeemable in lawful money (12 U.S.C. 411) .

Large-size notes

It has been suggested that Large-sized note be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2016. |

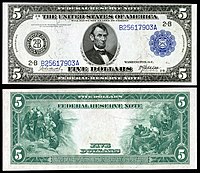

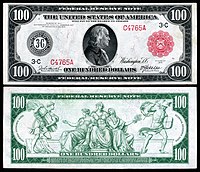

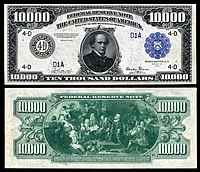

Series 1914 FRN were the first of two large-size issues. Denominations were $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 printed first with a red seal and then continued with a blue seal.[9] Series 1918 notes were issued in $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 denominations. The latter two denominations exist only in institutional collections.[10] Series 1914 and 1918 notes in the following two tables are from the National Numismatic Collection at the National Museum of American History (Smithsonian Institution).

Large size notes represent the earlier types or series of U.S. banknotes. Their "average" dimension is 7.375 x 3.125 inches (187 x 79 mm). Small size notes (described as such due to their size relative to the earlier large size notes) are an "average" 6.125 x 2.625 inches (156 x 67 mm), the size of modern U.S. currency. "Each measurement is +/- 0.08 inches (2mm) to account for margins and cutting"

Series 1914

| Value | Fr. | Red Seal | Blue Seal | Portrait and engraving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $5 | 832a 848 |

|

|

Abraham Lincoln |

| $10 | 894b 919a |

|

|

Andrew Jackson |

| $20 | 958a 1010 |

|

|

Grover Cleveland |

| $50 | 1019a 1053 |

|

|

Ulysses S. Grant |

| $100 | 1074a 1131 |

|

|

Benjamin Franklin |

Series 1918

| Value | Fr. | Image | Portrait and engraving |

|---|---|---|---|

| $500 | 1132d |

|

John Marshall |

| $1,000 | 1133d |

|

Alexander Hamilton |

| $5,000 | 1134d |

|

James Madison |

| $10,000 | 1135d |

|

Salmon P. Chase |

Production and distribution

A commercial bank that maintains a reserve account with the Federal Reserve can obtain notes from the Federal Reserve Bank in its district whenever it wishes. The bank must pay the face value of the notes by debiting (drawing down) its reserve account. Smaller banks without a reserve account at the Federal Reserve can maintain their reserve accounts at larger "correspondent banks" which themselves maintain reserve accounts with the Federal Reserve.[11]

Federal Reserve Notes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), a bureau of the Department of the Treasury.[12] When Federal Reserve Banks require additional notes for circulation, they must post collateral in the form of direct federal obligations, private bank obligations, or assets purchased through open market operations.[13] If the notes are newly printed, they also pay the BEP for the cost of printing (about 4¢ per note). This differs from the issue of coins, which are purchased for their face value.[11]

A Federal Reserve Bank can retire notes that return from circulation by exchanging them for collateral that the bank posted for an earlier issue. Retired notes in good condition are held in the bank's vault for future issues.[14] Notes in poor condition are destroyed[15] and replacements are ordered from the BEP. The Federal Reserve shreds 7,000 tons of worn out currency each year.[16]

Federal Reserve notes, on average, remain in circulation for the following periods of time:[17]

| Denomination | $1 | $5 | $10 | $20 | $50 | $100 |

| Years in circulation | 5.8 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 15.0 |

The Federal Reserve does not publish an average life span for the $2 bill. This is likely due to its treatment as a collector's item by the general public; it is, therefore, not subjected to normal circulation.[18]

Starting with the Series 1996 $100 note, bills $5 and above have a special letter in addition to the prefix letters which range from A-L. For series 1996, the first letter is A, for series 1999, the first letter is B, for series 2001, the first letter is C, for series 2003, the first letter is D, for series 2003A, the first letter is F, for series 2006, the first letter is H, and for series 2006A, the first letter is K.[19]

The Series 2004 $20, the first note in the second redesign, has kept the element of the special double prefix. For series 2004, the first letter is E, for series 2004A, the first letter is G, for series 2006, the first letter is I, for series 2009, the first letter is J, for series 2009A, the first letter is L, and for series 2013, the first letter is M.[19]

Federal Reserve Notes are made of 75% cotton and 25% linen fibers.[20]

Nicknames

U.S. paper currency has had many nicknames and slang terms. The notes themselves are generally referred to as bills (as in "five-dollar bill") and any combination of U.S. notes as bucks (as in "fifty bucks"), or, much less commonly, bones or beans. Notes can be referred to by the first or last name of the person on the portrait (George for One Dollar,[21] or even more popularly, "Benjamins" for $100 notes).

- See tables below for nicknames for individual denomination

- Greenbacks, any amount in any denomination of Federal Reserve Note (from the green ink used on the back). The Demand Notes issued in 1861 had green-inked backs, and the Federal Reserve Note of 1914 copied this pattern.

- "dead presidents", any amount in any denomination of Federal Reserve Note (from the portrait of a U.S. president on most denominations).

- Toms for the picture of Thomas Jefferson on the two-dollar bill.

- fin, finif (from the Yiddish word for five), or finski is a slang term for a five-dollar bill.

- sawbuck is a slang term for a ten-dollar bill, from the image of the Roman numeral X.

- double sawbuck is slang term for a twenty-dollar bill, from the image of the Roman numeral XX, and in some cases can be used to denote a pair of ten-dollar bills, which would be double sawbucks, depending on the situation and type and amount of currency on hand.

- One hundred dollar bills are sometimes called "Benjamins" (in reference to their portrait of Benjamin Franklin) or C-Notes (the letter "C" is the Roman numeral 100).

- One thousand dollars ($1000) can be referenced as "Large", "K" (short for "kilo"), "Grand" or "Stack", and as a "G" (short for "grand").

- In Raymond Chandler's novel, The Long Goodbye, the protagonist Marlowe refers to a five thousand dollar bill as "a portrait of Madison", due to the president portrayed on the bill being James Madison.

- Fed Shreds is the nickname for paper money that the United States government finds unfit for circulation and consequently shreds.[22]

Many more slang terms refer to money in general (green stamps, moolah, paper, bread, dough, do-re-mi, freight, loot, cheese, cake, stacks, greenmail, jack, rabbit, cabbage, pie, cheddar, scrilla, scratch, etc.).[citation needed]

Criticisms

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

Security

Despite the relatively late addition of color and other anti-counterfeiting features to U.S. currency, critics[who?] hold that it is still a straightforward matter to counterfeit these bills. They point out that the ability to reproduce color images is well within the capabilities of modern color printers, most of which are affordable to many consumers. These critics suggest that the Federal Reserve should incorporate holographic features, as are used in most other major currencies, such as the pound sterling, Canadian dollar and euro banknotes, which are more difficult and expensive to forge. Another robust technology, the polymer banknote, has been developed for the Australian dollar and adopted for the New Zealand dollar, Romanian leu, Papua New Guinea kina, Canadian dollar, and other circulating, as well as commemorative, banknotes of a number of other countries. Polymer banknotes are a deterrent to the counterfeiter, as they are much more difficult and time consuming to reproduce. They are said to be more secure, cleaner and more durable than paper notes.[23] One major issue with implementing these or any new counterfeiting countermeasures, however, is that (other than under Executive Order 6102) the United States has never demonetized or required a mandatory exchange of existing currency. Consequently, would-be counterfeiters can easily circumvent any new security features simply by counterfeiting older designs.

U.S. currency does, however, bear several anti-counterfeiting features. Two of the most critical anti-counterfeiting features of U.S. currency are the paper and the ink. The exact composition of the paper is classified,[citation needed] as is the formula for the ink. The ink and paper combine to create a distinct texture, particularly as the currency is circulated. The paper and the ink alone have no effect on the value of the dollar until post print. These characteristics can be hard to duplicate without the proper equipment and materials. Furthermore, recent redesigns of the $5, $10, $20, and $50 notes have added EURion constellation patterns which can be used by scanning software to recognize banknotes and refuse to scan them.

The differing sizes of other nations' banknotes are a security feature that eliminates one form of counterfeiting to which U.S. currency is prone: Counterfeiters can simply bleach the ink off a low-denomination note, such as a $1 or $5 bill, and reprint it as a higher-value note, such as a $100 bill. To counter this, the U.S. government has included in all $5 and higher denominated notes since the 1990 series a vertical laminate strip imprinted with denomination information, which under ultraviolet light fluoresces a different color for each denomination ($5 note: blue; $10 note: orange; $20 note: green; $50 note: yellow; $100 note: red).[24]

According to the central banks, the number of counterfeited bank notes seized annually is about 10 in one million of real bank notes for the Swiss franc, of 50 in one million for the Euro, of 100 in one million for United States dollar and of 300 in one million for Pound sterling.[25]

Differentiation

Critics, such as the American Council of the Blind, note that U.S. bills are relatively hard to tell apart: they use very similar designs, they are printed in the same colors (until the 2003 banknotes, in which a faint secondary color was added), and they are all the same size. The American Council of the Blind has argued[26] that American paper currency design should use increasing sizes according to value and/or raised or indented features to make the currency more usable by the vision-impaired, since the denominations cannot currently be distinguished from one another non-visually. Use of Braille codes on currency is not considered a desirable solution because (1) these markings would only be useful to people who know how to read Braille, and (2) one Braille symbol can become confused with another if even one bump is rubbed off. Though some blind individuals say that they have no problems keeping track of their currency because they fold their bills in different ways or keep them in different places in their wallets, they nevertheless must rely on sighted people or currency-reading machines to determine the value of each bill before filing it away using the system of their choice. This means that no matter how organized they are, blind people still have to trust sighted people or machines each time they receive US banknotes.

By contrast, other major currencies, such as the pound sterling and euro, feature notes of differing sizes: the size of the note increases with the denomination and different denominations are printed in different, contrasting colors. This is useful not only for the vision-impaired; they nearly eliminate the risk that, for example, someone might fail to notice a high-value note among low-value ones.

Multiple currency sizes were considered for U.S. currency, but makers of vending machines and change machines successfully argued that implementing such a wide range of sizes would greatly increase the cost and complexity of such machines. Similar arguments were unsuccessfully made in Europe prior to the introduction of multiple note sizes.

Alongside the contrasting colors and increasing sizes, many other countries' currencies contain tactile features missing from U.S. banknotes to assist the blind. For example, Canadian banknotes have a series of raised dots (not Braille) in the upper right corner to indicate denomination. Mexican peso banknotes also have raised patterns of dashed lines. The Indian Rupee has raised patterns of different shapes printed for various denominations on the left of the watermark window (20: vertical rectangle, 50: square, 100: triangle, 500: circle, 1,000: diamond).

Suit by the blind over U.S. banknote design

Ruling on a lawsuit filed in 2002 (American Council of the Blind v. Paulson), on November 28, 2006, U.S. District Judge James Robertson ruled that the American bills gave an undue burden to the blind and denied them "meaningful access" to the U.S. currency system. In his ruling, Robertson noted that the United States was the only nation out of 180 issuing paper currency that printed bills that were identical in size and color in all their denominations and that the successful use of such features as varying sizes, raised lettering and tiny perforations used by other nations is evidence that the ordered changes are feasible.[27] The plaintiff's attorney was quoted as saying "It's just frankly unfair that blind people should have to rely on the good faith of people they have never met in knowing whether they've been given the correct change."[citation needed] Government attorneys estimated that the cost of such a change ranges from $75 million in equipment upgrades and $9 million annual expenses for punching holes in bills to $178 million in one-time charges and $50 million annual expenses for printing bills of varying sizes.[28]

Robertson accepted the plaintiff's argument that current practice violates Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.[29] The judge ordered the Treasury Department to begin working on a redesign within 30 days,[26][30][31][32] but the Treasury appealed the decision.

On May 20, 2008, in a 2-to-1 decision, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the earlier ruling, pointing out that the cost estimates were inflated and that the burdens on blind and visually impaired currency users had not been adequately addressed.[33]

As a result of the court's injunction, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing is planning to implement a raised tactile feature in the next redesign of each note, except the $1 bill (which is by law not allowed to be redesigned[34][35]), though the version of the $100 bill already is in progress. It also plans larger, higher-contrast numerals, more color differences, and distribution of currency readers to assist the visually impaired during the transition period.[36] The Bureau received a comprehensive study on accessibility options in July 2009, and solicited public comments from May to August 2010.[37]

Design regulations

There are a few regulations to which the U.S. Treasury must adhere when redesigning banknotes. The national motto "In God We Trust" must appear on all U.S. currency and coins.[38] Though the motto had periodically appeared on coins since 1865, it did not appear on currency (other than interest-bearing notes in 1861) until a law passed in 1956 required it.[39] It began to appear on Federal Reserve Notes were delivered from 1964 to 1966, depending on denomination.[40]

The portraits appearing on the U.S. currency can feature only deceased individuals, whose names should be included below each of the portraits.[38] Since the standardization of the bills in 1928, the Department of the Treasury has chosen to feature the same portraits on the bills. These portraits were decided upon in 1929 by a committee appointed by the Treasury. Originally, the committee had decided to feature U.S. presidents because they were more familiar to the public than other potential candidates. The Treasury altered this decision, however, to include three statesmen who were also well-known to the public: Alexander Hamilton (the first Secretary of the Treasury who appears on the $10 bill), Salmon P. Chase (the Secretary of the Treasury during the American Civil War who appeared on the now-uncirculated $10,000 bill), and Benjamin Franklin (a signer of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution, who appears on the $100 bill).[41] In 2016, the Treasury announced a number of design changes to the $5, $10 and $20 bills; to be introduced over the next ten years. The redesigns include:[42][43]

- The back of the $5 bill will be changed to showcase historical events at the pictured Lincoln Memorial by adding portaits of Marian Anderson (due to her famous performance there after being barred from Constitution Hall due to her race), Martin Luther King Jr.'s (due to his famous I Have A Dream speech), and Eleanor Roosevelt (who arranged Anderson's performance).

- The back of the $10 bill will be changed to show a 1913 march for women's suffrage in the United States, plus portraits of Sojourner Truth, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

- On the $20 bill, Andrew Jackson will move to the back (reduced in size, alongside the White House) and Harriet Tubman will appear on the front.

After an unsuccessful attempt in the proposed Legal Tender Modernization Act of 2001,[44] the Omnibus Appropriations Act of 2009 required that none of the funds set aside for either the Treasury or the Bureau of Engraving and Printing may be used to redesign the $1 bill.[45] This is because any change would affect vending machines and the risk of counterfeiting is low for this small bill.[46] This superseded the Federal Reserve Act (Section 16, Paragraph 8) which gives the Treasury permission to redesign any banknote to prevent counterfeiting.[47]

Series detail

Series overview

| Series | Denominations | Obligation clause[48] |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | This note is receivable by all national and member banks and Federal Reserve Banks and for all taxes, customs and other public dues. It is redeemable in gold on demand at the Treasury Department of the United States in the city of Washington, District of Columbia or in gold or lawful money at any Federal Reserve Bank. |

| 1918 | $500, $1000, $5000, $10,000 |

| Series | Denominations | Obligation clause | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | $5, $10, $20, $50, $100, $500, $1000, $5000, $10,000 | Redeemable in gold on demand at the United States Treasury, or in gold or lawful money at any Federal Reserve Bank | Branch ID in numerals |

| 1934 | This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private, and is redeemable in lawful money at the United States Treasury, or at any Federal Reserve Bank | Branch ID in letters; during the Great Depression | |

| 1950 | $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | Slight design changes: branch logo; placements of signatures, "Series xxxx", and "Washington, D.C.", | |

| 1963, 1963A, 1963B, 1969, 1969A, 1969B, 1969C, 1974 | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private | First $1 FRN; "Will pay to the bearer on demand" removed; Seal in Latin replaced by seal in English in 1969[18] |

| 1976 | $2 | First $2 FRN, Bicentennial |

| Series | Denominations | Obligation clause |

|---|---|---|

| 1977, 1977A, 1981, 1981A, 1985, 1988, 1988A | $1, $5 | This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private |

| 1977, 1977A, 1981, 1981A, 1985, 1988A | $10, $20 | |

| 1977, 1981, 1981A, 1985, 1988 | $50, $100 | |

| 1990 | $10, $20, $50, $100 | |

| 1993 | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | |

| 1995 | $1, $2, $5, $10, $20 | |

| Large-portrait ($1 and $2 remain small-portrait) | ||

| 1996 | $20, $50, $100 | |

| 1999 | $1, $5, $10, $20, $100 | |

| 2001 | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | |

| 2003 | $1, $2, $5, $10, $100 | |

| 2003A | $1, $2, $5, $100 | |

| 2006 | $5, $100 | |

| 2006A | $100 | |

| Color notes ($1 and $2 remain unchanged) | ||

| 2004 | $20, $50 | |

| 2004A | $10, $20, $50 | |

| 2006 | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50 | |

| 2009 | $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | |

| 2009A | $100 | |

| 2013 | $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | |

Series 1914 (District Seals)

Series 1928–1995

| Small size notes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Description | Date of | |||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | first series | last series | |

|

|

$1 | George Washington | Great Seal of the United States | 1963 | current (2013) |

|

|

$2 | Thomas Jefferson | Trumbull's Declaration of Independence | 1976 | current (2013) |

| $5 | Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | 1928 | 1995 | ||

| $10 | Alexander Hamilton | Treasury Department Building | ||||

| $20 | Andrew Jackson | White House | ||||

| File:US $50 1993 Federal Reserve Note Obverse.jpg | File:US $50 1993 Federal Reserve Note Reverse.jpg | $50 | Ulysses S. Grant | United States Capitol | 1993 | |

| $100 | Benjamin Franklin | Independence Hall | ||||

| $500 | William McKinley | "Five Hundred Dollars" | 1934 | |||

| $1000 | Grover Cleveland | "One Thousand Dollars" | ||||

| $5000 | James Madison | "Five Thousand Dollars" | ||||

| $10,000 | Salmon P. Chase | "Ten Thousand Dollars" | ||||

Series 1996–2003 (New Currency Design)

| Small size notes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Description | series | |||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | first | last | |

|

|

$5 | As small-size, small-portrait notes | 1999 | 2006 | |

|

|

$10 | 2003 | |||

|

|

$20 | 1996 | 2001 | ||

|

|

$50 | ||||

|

|

$100 | 2006A (See Note, below) | |||

Note - The series 2006A was produced from 2011 to 2013 due to issues with the printing process for the colorized (NextGen) $100 notes.

Post-2004 redesigned series (NextGen)

Beginning in 2003, the Federal Reserve introduced a new series of bills, featuring images of national symbols of freedom. The new $20 bill was first issued on October 9, 2003; the new $50 on September 28, 2004; the new $10 bill on March 2, 2006; the new $5 bill on March 13, 2008; the new $100 bill on October 8, 2013. The one and two dollar bills still remain small portrait, unchanged, and not watermarked.

| Color series | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Value | Background color | Description | Date of | ||||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | first series | Issue | ||

|

|

$5 | Purple | President Abraham Lincoln; Great Seal of the United States | Lincoln Memorial | Two Watermarks of the Number "5" | 2006 | March 13, 2008 |

|

|

$10 | Orange | Secretary Alexander Hamilton; The phrase "We the People" from the United States Constitution and the torch of the Statue of Liberty | Treasury Building | Alexander Hamilton | 2004 A | March 2, 2006 |

|

|

$20 | Green | President Andrew Jackson; Eagle | White House | Andrew Jackson | 2004 | October 9, 2003 |

|

|

$50 | Pink | President Ulysses S. Grant; Flag of the United States | United States Capitol | Ulysses S. Grant | 2004 | September 28, 2004 |

|

|

$100 | Teal | Benjamin Franklin; Declaration of Independence | Independence Hall | Benjamin Franklin | 2009A (See Note, below) | October 8, 2013 |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||

All small-sized bills measure 6.14 in × 2.61 in (156 mm × 66 mm), with thickness of 0.0043 in (0.11 mm).

Note - While the series 2009A was the first released for circulation, the first printing was series 2009 printed in 2010 & 2011. These were withheld from circulation due to issues with the printing process and none were released until 2016.

See also

References

- This article incorporates text from the website of the US Treasury, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 255. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ codified at 12 U.S.C. § 411

- ^ a b "Section 411 of Title 12 of the United States Code". Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ Bryan A. Garner, editor, Black's Law Dictionary 8th ed. (West Group, 2004) ISBN 0-314-15199-0.

- ^ Section 415 of Title 12 of the United States Code. Section 415 describes circulating Federal Reserve Notes as liabilities of the issuing Federal Reserve Bank.

- ^ See generally 31 U.S.C. § 5103.

- ^ Federal Reserve Act Section 16

- ^ Cross, Ira B. (June 1938). "A Note on Lawful Money". The Journal of Political Economy. 46 (3): 409–413. doi:10.1086/255236.

- ^ Friedberg & Friedberg, 2013, p. 148.

- ^ Friedberg & Friedberg, 2013, pp. 157–59.

- ^ a b Federal Reserve Bank of New York (April 2007). "How Currency Gets into Circulation". Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury. "Organization chart of the Department of the Treasury" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ 12 U.S.C. § 412

- ^ 12 U.S.C. § 416

- ^ 12 U.S.C. § 413

- ^ Fleur-de-coin.com. "US Coin Facts". Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ Federal Reserve System (2013-10-08). "How long is the life span of U.S. paper money?". Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- ^ a b USPaperMoney.info. "History of Currency Designs - A last few changes, and then stability". Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ a b "USPaperMoney.Info: Details of Serial Numbering". uspapermoney.info. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ^ "What is money made out of". USA.gov, the U.S. government's official web portal. December 29, 2011. Retrieved 2015-06-20.

- ^ "Where's George? ® 2.4 - Track Your Dollar Bills". Wheresgeorge.com. 2011-09-22. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ "FED". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ Note Printing Australia (March 2008). "Polymer substrate - the foundation for a secure banknote=2008-03-15".

- ^ Anti-Counterfeiting: Security Features. The United States Treasury Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Accessed 11 January 2012.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Michel Beuret, "Les mystères de la fausse monnaie", Allez savoir !, no. 50, May 2011.

- ^ a b "Judge rules paper money unfair to blind". CNNMoney.com. 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ "Government appeals currency redesign". USA Today. Associated Press. 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "Judge: Make Money Recognizable to Blind". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 29 November 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ AMERICAN COUNCIL OF THE BLIND,

et al. v. Henry M. Paulson, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury, Civil Action No. 02-0864 (JR) (United States District Court for the District of Columbia 2002).

Archived 2007-02-16 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Bridges, Eric, ed. (6 October 2008). "Court Says Next Gen Currency Must Be Accessible to the Blind" (Press release). American Council of the Blind. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Court Says the Blind Will Have Meaningful Access to Currency, Tells Government 'No Unnecessary Delays'

- ^ Federal Court Tells U.S. Treasury Department That It Must Design and Issue Accessible Paper Currency

- ^ "Court rules paper money unfair to blind". CNNMoney.com. 2008-05-20. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ [1], Footnote on page 3

- ^ "Administrative Provisions : Department of the Treasury". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ "Federal Register, Volume 75 Issue 97 (Thursday, May 20, 2010)". Edocket.access.gpo.gov. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ The study, request for comments, and public comments filed before the August deadline can be read in the Federal Register; see http://www.bep.treas.gov/uscurrency/meaningfulaccess.html

- ^ a b 31 U.S.C. § 5114

- ^ Public Law 84-140

- ^ "History of 'In God We Trust'". treasury.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- ^ "U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing - FAQ Library". Moneyfactory.gov. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/21/us/women-currency-treasury-harriet-tubman.html

- ^ "Anti-slavery activist Harriet Tubman to replace Jackson on $20 bill". usatoday.com. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ^ H.R. 2528

- ^ H.R. 1105

- ^ Mimms, Sarah. "Why the $1 bill hasn't changed since 1929". Quartz (publication). Atlantic Media. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "FRB: Federal Reserve Act: Section 16". Federalreserve.gov. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ Devoted to Truth. "Evolution from Gold to Fiat Money". Retrieved 2008-02-19.

External links

- Bureau of Engraving and Printing

- Six Kinds of United States Paper Currency

- Federal Reserve Act: Section 16—The Federal Reserve Board