Florida panther: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 573813735 by 168.11.52.2 (talk) |

Tag: nonsense characters |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

Florida Panthers are spotted at birth and typically have blue eyes. As the panther grows the spots fade and the coat becomes completely tan while the eyes typically take on a yellow hue. The panther's underbelly is a creamy white, with black tips on the tail and ears. Florida panthers lack the ability to roar, and instead make distinct sounds that include whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. Florida panthers are mid-sized for the species, being smaller than cougars from Northern and Southern climes but larger than cougars from the [[neotropic]]s. Adult female Florida panthers weigh {{convert|29|-|45.5|kg|lb|abbr=on}} whereas the larger males weigh {{convert|45.5|-|72|kg|abbr=on}}. Total length is from {{convert|1.8|to|2.2|m|ft|abbr=on}} and shoulder height is {{convert|60|-|70|cm|in|abbr=on}}.<ref>[http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw176 WEC 167/UW176: Jaguar: Another Threatened Panther]. Edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.</ref><ref>[http://www.floridapanthernet.org/index.php/handbook/history/physical_description/ PantherNet : Handbook: Natural History : Physical Description]. Floridapanthernet.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.</ref> |

Florida Panthers are spotted at birth and typically have blue eyes sdfjiopdjghSGYUDYSADOGFYUSGFYUDGAYDGBCYDBUCDYagfUAGSDBCGFIUVuscvsagfuiAFSUIVasduVSADUVasdvIAVSDfusavAFsuSAYavuIASAFUGYusAGFBUXZbyAFYUZSFUBUfuIAFS ASF. As the panther grows the spots fade and the coat becomes completely tan while the eyes typically take on a yellow hue. The panther's underbelly is a creamy white, with black tips on the tail and ears. Florida panthers lack the ability to roar, and instead make distinct sounds that include whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. Florida panthers are mid-sized for the species, being smaller than cougars from Northern and Southern climes but larger than cougars from the [[neotropic]]s. Adult female Florida panthers weigh {{convert|29|-|45.5|kg|lb|abbr=on}} whereas the larger males weigh {{convert|45.5|-|72|kg|abbr=on}}. Total length is from {{convert|1.8|to|2.2|m|ft|abbr=on}} and shoulder height is {{convert|60|-|70|cm|in|abbr=on}}.<ref>[http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw176 WEC 167/UW176: Jaguar: Another Threatened Panther]. Edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.</ref><ref>[http://www.floridapanthernet.org/index.php/handbook/history/physical_description/ PantherNet : Handbook: Natural History : Physical Description]. Floridapanthernet.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.</ref> |

||

==Taxonomic status== |

==Taxonomic status== |

||

Revision as of 19:04, 20 September 2013

| Florida Panther | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. c. coryi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Puma concolor coryi Bangs, 1899

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Proposed taxonomic revision: aggregation with other subspecies of Puma concolor into a single subspecies of North American cougar, P. c. couguar,[1] based on genetic work.[2] | |

The Florida panther is an endangered subspecies of cougar (Puma concolor) that lives in forests and swamps of southern Florida in the United States. Its current taxonomic status (Puma concolor coryi or Puma concolor couguar) is unresolved, but recent genetic research alone does not alter the legal conservation status. This species is also known as the cougar, mountain lion, puma, and catamount; but in the southeastern United States and particularly Florida, it is exclusively known as the panther.

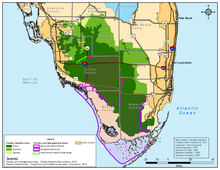

Males can weigh up to 160 pounds (73 kg)[3] and live within a range that includes the Big Cypress National Preserve, Everglades National Park, and the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge.[4] This population, the only unequivocal cougar representative in the eastern United States, currently occupies 5% of its historic range. In the 1970s, there were an estimated 20 Florida panthers in the wild, and their numbers have increased to an estimated 100 to 160 as of 2011.[5]

In 1982, the Florida panther was chosen as the Florida state animal.[6]

Description

Florida Panthers are spotted at birth and typically have blue eyes sdfjiopdjghSGYUDYSADOGFYUSGFYUDGAYDGBCYDBUCDYagfUAGSDBCGFIUVuscvsagfuiAFSUIVasduVSADUVasdvIAVSDfusavAFsuSAYavuIASAFUGYusAGFBUXZbyAFYUZSFUBUfuIAFS ASF. As the panther grows the spots fade and the coat becomes completely tan while the eyes typically take on a yellow hue. The panther's underbelly is a creamy white, with black tips on the tail and ears. Florida panthers lack the ability to roar, and instead make distinct sounds that include whistles, chirps, growls, hisses, and purrs. Florida panthers are mid-sized for the species, being smaller than cougars from Northern and Southern climes but larger than cougars from the neotropics. Adult female Florida panthers weigh 29–45.5 kg (64–100 lb) whereas the larger males weigh 45.5–72 kg (100–159 lb). Total length is from 1.8 to 2.2 m (5.9 to 7.2 ft) and shoulder height is 60–70 cm (24–28 in).[7][8]

Taxonomic status

The Florida panther has long been considered a unique subspecies of cougar, under the trinomial Puma concolor coryi (Felis concolor coryi in older listings), one of thirty-two subspecies once recognized. The Florida panther has been protected from legal hunting since 1958, and in 1967 it was listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; it was added to the state's endangered species list in 1973.[6][9]

A genetic study of cougar mitochondrial DNA has reported that many of the supposed subspecies are too similar to be recognized as distinct,[2] suggesting a reclassification of the Florida panther and numerous other subspecies into a single North American cougar (Puma concolor couguar). Following the research, the canonical Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition) ceased to recognize the Florida panther as a unique subspecies, collapsing it and others into the North American cougar.[1]

Despite these findings it is still listed as subspecies Puma concolor coryi in research works, including those directly concerned with its conservation.[10] Responding to the research that suggested removing its subspecies status, the Florida Panther Recovery Team noted in 2007 "the degree to which the scientific community has accepted the results of Culver et al. and the proposed change in taxonomy is not resolved at this time."[11][dead link]

Diet

The Florida panther's diet consists of small animals like hares, mice, and waterfowl but also larger animals like storks, white-tailed deer, and wild boar.[citation needed]

Threats

The Florida panther has a natural predator, the alligator. Humans also threaten it through poaching and wildlife control measures. Besides predation, the biggest threat to their survival is human encroachment. Historical persecution reduced this wide-ranging, large carnivore to a small area of south Florida. This created a tiny isolated population that became inbred (revealed by kinked tails, heart, and sperm problems).[12]

The two highest causes of mortality for individual Florida panthers are automobile collisions and territorial aggression between panthers.[13] When these incidents don't kill and only injure the panthers, federal and Florida wildlife officials take them to White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida for recovery and rehabilitation until they are well enough to be reintroduced.[14] Additionally, White Oak raises orphaned cubs and has done so for 12 individuals. Most recently, an orphaned brother and sister were brought to the center at 5 months old in 2011 after their mother was found dead in Collier County, Florida.[15] After being raised, the male and female were released in early 2013 to the Rotenberger Wildlife Management Area and Collier County, respectively.[16]

Primary threats to the population as a whole include habitat loss, habitat degradation, and habitat fragmentation. Southern Florida is a fast-developing area and certain developments such as Ave Maria near Naples, are controversial for their location in prime panther habitat.[17]

Development and the Caloosahatchee River are major barriers to natural population expansion. While young males wander over extremely large areas in search of an available territory, females occupy home ranges close to their mothers. For this reason, cougars/panthers are poor colonizers and expand their range slowly despite occurrences of males far away from the core population.

Conservation status

It was formerly considered Critically Endangered by the IUCN, but it has not been listed since 2008. Recovery efforts are currently underway in Florida to conserve the state's remaining population of native panthers. This is a difficult task, as the panther requires contiguous areas of habitat — each breeding unit, consisting of one male and two to five females, requires about 200 square miles (500 km2) of habitat.[18] A population of 240 panthers would require 8,000 to 12,000 square miles (31,000 km2) of habitat and sufficient genetic diversity in order to avoid inbreeding as a result of small population size. The introduction of eight female cougars from a closely related Texas population has apparently been successful in mitigating inbreeding problems.[19] One objective to panther recovery is establishing two additional populations within historic range, a goal that has been politically difficult.[20]

Management controversy

The Florida panther has been at the center of a controversy over the science used to manage the species. There has been very strong disagreement between scientists about the location and nature of critical habitat. This in turn is linked to a dispute over management which involves property developers and environmental organizations.[21] Recovery agencies appointed a panel of four experts, the Florida Panther Scientific Review Team (SRT), to evaluate the soundness of the body of work used to guide panther recovery. The SRT identified serious problems in panther literature, including mis-citations and misrepresentation of data to support unsound conclusions.[22][23][24] A Data Quality Act (DQA) complaint brought by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) and Andrew Eller, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), was successful in demonstrating that agencies continued to use incorrect data after it had been clearly identified as such.[25] As a result of the DQA ruling, USFWS admitted errors in the science the agency was using and subsequently reinstated Eller, who had been fired by USFWS after filing the DQA complaint. In two white papers, environmental groups contended that habitat development was permitted that should not have been, and documented the link between incorrect data and financial conflicts of interest.[26][27]In January 2006, USFWS released a new Draft Florida Panther Recovery Plan for public review.[28]

The Florida panther in fiction

A Florida panther is one of the main characters of the young adult novel Scat by Carl Hiaasen.

A Florida panther in a sanctuary figures in the penultimate chapter of Humana Festa (2008) by Brazilian novelist Regina Rheda. In the English translation (2012), the animal is referred to as "cougar" to maintain effective wordplay.

A Florida panther was a major character in the 1998 Boxcar Children book The Panther Mystery.

References

- ^ a b Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Culver, M. (2000). "Genomic Ancestry of the American Puma" (PDF). Journal of Heredity. 91 (3): 186–197. doi:10.1093/jhered/91.3.186. PMID 10833043.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Florida Panther General Information". Florida Panther Society. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ^ FLORIDA PANTHER. Division of Endangered Species, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Last Retrieved 2007-01-30. Archived 2008-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "msnbc.com Video Player". MSNBC. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- ^ a b "The State Animal: Florida Panther". Division of Historical Resources. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ WEC 167/UW176: Jaguar: Another Threatened Panther. Edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.

- ^ PantherNet : Handbook: Natural History : Physical Description. Floridapanthernet.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-02.

- ^ "Florida Panther". Endangered and Threatened Species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1993. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Conroy, Michael J. (2006). Morrison (ed.). "Improving The Use Of Science In Conservation: Lessons From The Florida Panther" (subscription required). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1:ITUOSI]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Florida Panther Recovery Team (2006-01-31). "Florida Panther Recovery Program (Draft)" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sivlerstein, Alvin (1997). The Florida Panther. Brooksville, Connecticut: Millbrook Press. pp. 41+. ISBN 0-7613-0049-X.

- ^ "The Florida Panther". Sierra Club Florida. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "BACK TO THE WILD". Friends of the Florida Panther Refuge. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Staats, Eric. "Orphaned Florida panther kittens rescued". Naples Daily News. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Fleshler, David. "First Florida panther released into Palm Beach County". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Staats, Eric (January 27, 2004). "Sierra Club Says Ave Maria Will 'Threaten' Everglades". Naples Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Florida Panther Recovery Plan. The Florida Panther Recovery Team, South Florida Ecological Services Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 1995-03-13. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Florida Panther and the Genetic Restoration Program. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Pittman, Craig (December 18, 2008). "Florida panthers need new territory, federal officials say". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, FL. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ^ Gross L (2005). "Why Not the Best? How Science Failed the Florida Panther". PLoS Biol. 3 (9): e333. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030333.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Beier, P; Vaughan, MR; Conroy, MJ and Quigley, H. 2003, An analysis of scientific literature related to the Florida panther: Submitted as final report for Project NG01-105, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, FL.

- ^ Beier, P; Vaughan, MR; Conroy, MJ and Quigley, H (2006). "Evaluating scientific inferences about the Florida panther" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70: 236–245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Conroy, MJ, P Beier, H Quigley, and MR Vaughan (2006). "Improving the use of science in conservation: lessons from the Florida panther" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 70: 1–7. doi:10.2193/0022-541X(2006)70[1:ITUOSI]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Information Quality Guidelines: Your Questions and Our Responses. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 2005-03-21. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Kostyack, J and Hill, K. 2005. Giving Away the Store.

- ^ Kostyack, J and Hill, K. 2004. Discrediting a Decade of Panther Science: Implications of the Scientific Review Team Report.

- ^ Fish and Wildlife Service releases Draft Florida Panther Recovery Plan for public review. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Published 2006-01-31. Retrieved 2007-01-30.