Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions comprise four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish the standards of international law for the humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term Geneva Convention usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–45), which updated the terms of the first three treaties (1864, 1906, 1929), and added a fourth. The Geneva Conventions extensively defined the basic rights of wartime prisoners (civilians and military personnel); established protections for the wounded and sick; and established protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in whole or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1] Moreover, the Geneva Convention also defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants, yet, because the Geneva Conventions are about people in war, the articles do not address warfare proper—the use of weapons of war—which is the subject of the Hague Conventions (First Hague Conference, 1899; Second Hague Conference 1907), and the bio-chemical warfare Geneva Protocol (Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, 1925).

History

The Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, A Memory of Solferino, in 1862, on the horrors of war.[2] His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

- A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

- A government treaty recognizing the neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers in the battlefield. For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became corecipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.[3][4]

The ten articles of this first treaty were initially adopted on 22 August 1864 by twelve nations.[5] Clara Barton was instrumental in campaigning for the ratification of the 1864 Geneva Convention by the United States, which eventually ratified it in 1882.[6]

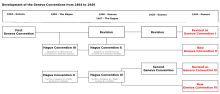

The second treaty was first adopted in the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies at Sea, concluded on 6 July 1906 and specifically addressed members of the Armed Forces at sea.[7] It was continued in the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, concluded on 27 July 1929 and entered into effect on 19 June 1931.[8] Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior three Geneva Conventions and adding a new elaborate Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. In fact, the very nature of armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality:[9] on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric. Moreover, modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, thus bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

Contents

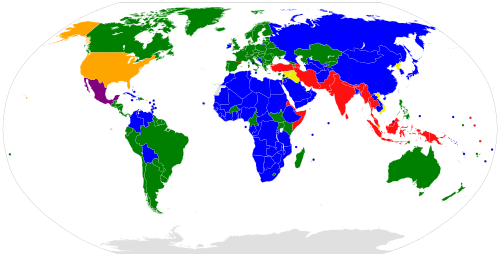

Parties to GC I–IV and P I–III | Parties to GC I–IV and P I–II |

Parties to GC I–IV and P I and III | Parties to GC I–IV and P I |

Parties to GC I–IV and P III | Parties to GC I–IV and no P |

The Geneva Conventions are rules that apply only in times of armed conflict and seek to protect people who are not or are no longer taking part in hostilities; these include the sick and wounded of armed forces on the field, wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, prisoners of war, and civilians. The first convention dealt with the treatment of wounded and sick armed forces in the field.[10] The second convention dealt with the sick, wounded, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea.[11][12] The third convention dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war during times of conflict; the conflict in Vietnam greatly contributed to this revision of the Geneva Convention.[13] The fourth convention dealt with the treatment of civilians and their protection during wartime.[14]

Conventions

In diplomacy, the term convention does not have its common meaning as an assembly of people. Rather, it is used in diplomacy to mean an international agreement, or treaty. The first three Geneva Conventions were revised, expanded, and replaced, and the fourth one was added, in 1949.

- The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field was adopted in 1864. It was significantly revised and replaced by the 1906 version,[15] the 1929 version, and later the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.[16]

- The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea was adopted in 1906.[17] It was significantly revised and replaced by the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.[18]

- The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was adopted in 1929.[19] It was significantly revised and replaced by the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.[20]

- The Fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War was adopted in 1949.[21]

With three Geneva Conventions revised and adopted, and the fourth added, in 1949 the whole set is referred to as the "Geneva Conventions of 1949" or simply the "Geneva Conventions". The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in whole or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1]

Protocols

The 1949 conventions have been modified with three amendment protocols:

- Protocol I (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts[22]

- Protocol II (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts[23]

- Protocol III (2005) relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem.[24]

Application

The Geneva Conventions apply at times of war and armed conflict to governments who have ratified its terms. The details of applicability are spelled out in Common Articles 2 and 3. The topic of applicability has generated some controversy. When the Geneva Conventions apply, governments have surrendered some of their national sovereignty by signing these treaties.

Common Article 2 relating to international armed conflicts

This article states that the Geneva Conventions apply to all cases of international conflict, where at least one of the warring nations have ratified the Conventions. Primarily:

- The Conventions apply to all cases of declared war between signatory nations. This is the original sense of applicability, which predates the 1949 version.

- The Conventions apply to all cases of armed conflict between two or more signatory nations, even in the absence of a declaration of war. This language was added in 1949 to accommodate situations that have all the characteristics of war without the existence of a formal declaration of war, such as a police action.[12]

- The Conventions apply to a signatory nation even if the opposing nation is not a signatory, but only if the opposing nation "accepts and applies the provisions" of the Conventions.[12]

Article 1 of Protocol I further clarifies that armed conflict against colonial domination and foreign occupation also qualifies as an international conflict.

When the criteria of international conflict have been met, the full protections of the Conventions are considered to apply.

Common Article 3 relating to non-international armed conflict

This article states that the certain minimum rules of war apply to armed conflicts that are not of an international character, but that are contained within the boundaries of a single country. The applicability of this article rests on the interpretation of the term armed conflict.[12] For example, it would apply to conflicts between the Government and rebel forces, or between two rebel forces, or to other conflicts that have all the characteristics of war but that are carried out within the confines of a single country. A handful of individuals attacking a police station would not be considered an armed conflict subject to this article, but only subject to the laws of the country in question.[12]

The other Geneva Conventions are not applicable in this situation but only the provisions contained within Article 3,[12] and additionally within the language of Protocol II. The rationale for the limitation is to avoid conflict with the rights of Sovereign States that were not part of the treaties. When the provisions of this article apply, it states that:[25]

- Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria. To this end, the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons:

- violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

- taking of hostages;

- outrages upon dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; and

- the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

- The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.

Enforcement

Protecting powers

The term protecting power has a specific meaning under these Conventions. A protecting power is a state that is not taking part in the armed conflict, but that has agreed to look after the interests of a state that is a party to the conflict. The protecting power is a mediator enabling the flow of communication between the parties to the conflict. The protecting power also monitors implementation of these Conventions, such as by visiting the zone of conflict and prisoners of war. The protecting power must act as an advocate for prisoners, the wounded, and civilians.

Grave breaches

Not all violations of the treaty are treated equally. The most serious crimes are termed grave breaches, and provide a legal definition of a war crime. Grave breaches of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions include the following acts if committed against a person protected by the convention:

- willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including biological experiments

- willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health

- compelling a protected person to serve in the armed forces of a hostile power

- willfully depriving a protected person of the right to a fair trial if accused of a war crime.

Also considered grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention are the following:

- taking of hostages

- extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly

- unlawful deportation, transfer, or confinement.[26]

Nations who are party to these treaties must enact and enforce legislation penalizing any of these crimes.[27] [irrelevant citation] Nations are also obligated to search for persons alleged to commit these crimes, or persons having ordered them to be committed, and to bring them to trial regardless of their nationality and regardless of the place where the crimes took place.[citation needed]

The principle of universal jurisdiction also applies to the enforcement of grave breaches when the UN Security Council asserts its authority and jurisdiction from the UN Charter to apply universal jurisdiction. The UNSC did this when they established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to investigate and/or prosecute alleged violations.

Legacy

Although warfare has changed dramatically since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, they are still considered the cornerstone of contemporary international humanitarian law.[28] They protect combatants who find themselves hors de combat, and they protect civilians caught up in the zone of war. These treaties came into play for all recent international armed conflicts, including the War in Afghanistan,[29] the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion of Chechnya (1994–present),[30] and the 2008 War in Georgia. The Geneva Conventions also protect those affected by non-international armed conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War.[dubious – discuss]

The lines between combatants and civilians have blurred when the actors are not exclusively High Contracting Parties (HCP).[31] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, an HCP often is faced with a non-state actors,[32] as argued by General Wesley Clark in 2007.[33] Examples of such conflict include the Sri Lankan Civil War, the Sudanese Civil War, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, as well most military engagements of the US since 2000.

Some scholars hold that Common Article 3 deals with these situations, supplemented by Protocol II (1977).[dubious – discuss] These set out minimum legal standards that must be followed for internal conflicts. International tribunals, particularly the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), have clarified international law in this area.[34] In the 1999 Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic judgement, the ICTY ruled that grave breaches apply not only to international conflicts, but also to internal armed conflict.[dubious – discuss] Further, those provisions are considered customary international law.

Controversy has arisen over the US designation of irregular opponents as "unlawful enemy combatants" (see also unlawful combatant) especially in the SCOTUS judgments over the Guantanamo Bay brig facility Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and Rasul v. Bush,[35] and later Boumediene v. Bush. President George W. Bush, aided by Attorneys-General John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales and General Keith B. Alexander, claimed the power, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, to determine that any person, including an American citizen, who is suspected of being a member, agent, or associate of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or possibly any other terrorist organization, is an "enemy combatant" who can be detained in U.S. military custody until hostilities end, pursuant to the international law of war.[36][37][38]

The application of the Geneva Conventions to the 2014 conflict in Ukraine (Crimea) is a troublesome problem because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues.[39] American pilots in Operation Southern Watch were documented to bear no insignia, so as to gain some illusory intelligence advantage.[39] The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under jus in bello doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POW captured in this circumstance remains a question.

Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University,[40][41] the International Committee of the Red Cross,[42] and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.[43]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b "State Parties / Signatories: Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949". International Humanitarian Law. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Dunant, Henry. A Memory of Solferino. English version, full text online.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (2001). The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History, 1901–2001. US: Science History Publications. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ The story of an idea, film on the creation of the Red Cross, Red Crescent Movement and the Geneva Conventions

- ^ Roxburgh, Ronald (1920). International Law: A Treatise. London: Longmans, Green and co. p. 707. Retrieved 14 July 2009. The original twelve original countries were Switzerland, Baden, Belgium, Denmark, France, Hesse, the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Prussia, Spain, and Wurtemburg.

- ^ Burton, David (1995). Clara Barton: in the service of humanity. London: Greenwood Publishing Group. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Text of the 1906 convention (French)

- ^ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 118, pp. 304–341.

- ^ Kolb, Robert (2009). Ius in bello. Basel: Helbing Lichtenhahn. ISBN 978-2-8027-2848-1.

- ^ Sperry, C. (1906). "The Revision of the Geneva Convention, 1906". Proceedings of the American Political Science Association. 3: 33–57. JSTOR 3038537.

- ^ Yingling, Raymund (1952). "The Geneva Conventions of 1949". The American Journal of International Law. 46: 393–427. JSTOR 2194498.

- ^ a b c d e f Pictet, Jean (1958). Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Commentary. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "The Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War". The American Journal of International Law. 47: 119–117. 1953. JSTOR 2213912.

- ^ Bugnion, Francios (2000). "The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: From the 1949 Diplomatic Conference to the Dawn of the New Millennium". International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944–). 76: 41–51. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.00118. JSTOR 2626195.

- ^ "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 6 July 1906". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ 1949 Geneva Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field

- ^ David P. Forsythe (17 June 2007). The International Committee of the Red Cross: A Neutral Humanitarian Actor. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 0-415-34151-5.

- ^ wipo.int: "Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea", consulted July 2014

- ^ icrc.org: "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929.", consulted July 2014

- ^ umn.edu: "Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, 75 U.N.T.S. 135", consulted July 2014

- ^ wipo.int: "GENEVA CONVENTION RELATIVE TO THE PROTECTION OF CIVILIAN PERSONS IN TIME OF WAR OF AUGUST 12, 1949", consulted July 2014

- ^ treaties.un.org: "Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (Protocol I)"

- ^ treaties.un.org: "Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts (Protocol II)", consulted July 2014

- ^ "Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the adoption of an additional distinctive emblem (Protocol III)", consulted July 2014

- ^ "Article 3 of the Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949". Inter national Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ How "grave breaches" are defined in the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols, International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ For example, the War Crimes Act of 1996.

- ^ "The Geneva Conventions Today". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ See U.S. Supreme Court decision, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

- ^ Abresch, William (2005). "A Human Rights Law of Internal Armed Conflict: The European Court of Human Rights in Chechnya" (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 16 (4).

- ^ "Sixty years of the Geneva Conventions and the decades ahead". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Meisels, T: "COMBATANTS – LAWFUL AND UNLAWFUL" (2007 Law and Philosophy, v26 pp.31–65)

- ^ nytimes.com: "Why Terrorists Aren’t Soldiers" 8 Aug 2007

- ^ "The Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic – Case No. IT-94-1-A". International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ utretchtlawreview.org: "Guantánamo Bay: A Reflection On The Legal Status And Rights Of ‘Unlawful Enemy Combatants’ (Gill, van Sliedregt) v1 n1 Sep 2005

- ^ JK Elsea: "Presidential Authority to Detain 'Enemy Combatants'" (2002), for Congressional Research Service

- ^ presidency.ucsb.edu: "Press Briefing by White House Counsel Judge Alberto Gonzales, DoD General Counsel William Haynes, DoD Deputy General Counsel Daniel Dell'Orto and Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence General Keith Alexander June 22, 2004", consulted July 2014

- ^ nytimes.com: "Martial Justice, Full and Fair" (Gonzalez) 30 Nov 2001

- ^ a b vice.com: "The Russian Soldier Captured in Crimea May Not Be Russian, a Soldier, or Captured" 10 Mar 2014

- ^ "Training vs. Torture". President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Khouri, Rami. "International Law, Torture and Accountability". Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ "Advanced Seminar in International Humanitarian Law for University Lecturers". International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ McManus, Shani (13 July 2015). "Responding to terror explored". South Florida Sun-Sentinel.