German occupation of Lithuania during World War II

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Occupation of the Baltic states |

|---|

|

The military occupation of Lithuania by Nazi Germany lasted from the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, to the end of the Battle of Memel on January 28, 1945. At first the Germans were welcomed as liberators from the repressive Soviet regime which had occupied Lithuania. In hopes of re-establishing independence or regaining some autonomy, Lithuanians organized a Provisional Government that lasted six weeks.

Background

[edit]

In August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the German–Soviet Nonaggression Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol, dividing Central and Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Lithuania was initially assigned to the German sphere, likely due to its economic dependence on German trade. After the March 1939 ultimatum regarding the Klaipėda Region, Germany accounted for 75% of Lithuanian exports and 86% of its imports.[1] To solidify its influence, Germany suggested a German–Lithuanian military alliance against Poland and promised to return the Vilnius Region, but Lithuania held to its policy of strict neutrality.[2] When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Wehrmacht took control of the Lublin Voivodeship and eastern Warsaw Voivodeship, which were in the Soviet sphere of influence. To compensate the Soviet Union for this loss, a secret codicil to the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty transferred Lithuania to the Soviet sphere of influence,[3] which was the justification for the Soviet Union to occupying Lithuania on June 15, 1940 and establishing the Lithuanian SSR.

Almost immediately after the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, the Soviets pressured the Lithuanians into signing the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty. According to this treaty, Lithuania gained about 6,880 square kilometres (2,660 sq mi) of territory in the Vilnius Region (including Vilnius, Lithuania's historical capital) in return for allowing five Soviet military bases in Lithuania (total 20,000 troops).[4] The territories that Lithuania received from the Soviet Union were former territories of the Second Polish Republic, disputed between Poland and Lithuania since the Polish-Lithuanian War of 1920 and occupied by the Soviet Union following the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939. The Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty was described by The New York Times as a "virtual sacrifice of independence."[5] Similar pacts were proposed to Latvia, Estonia, and Finland. Finland was the only state to refuse, and that sparked the Winter War. This war delayed the occupation of Lithuania: the Soviets did not interfere with Lithuania's domestic affairs[6] and Russian soldiers were well-behaved in their bases.[7] As the Winter War ended in March and Germany was making rapid advances in the Battle of France, the Soviets heightened their anti-Lithuanian rhetoric and accused Lithuanians of kidnapping Soviet soldiers from their bases. Despite Lithuanian attempts to negotiate and resolve the issues, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum on June 14, 1940.[8] Lithuanians accepted the ultimatum and Soviet military took control of major cities by June 15. The following day identical ultimatums were issued to Latvia and Estonia. To legitimize the occupation, the Soviets staged elections to the so-called People's Seimas, which then asked to join the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.[9] This allowed Soviet propaganda claiming that Lithuania has voluntarily joined the Soviet Union.

Soon after the occupation started, Sovietization policies were implemented. On July 1, all political, cultural, and religious organizations were closed,[11] with only the Communist Party of Lithuania and its youth branch allowed to exist. All banks (including all accounts above 1,000 litas), real estate larger than 170 square metres (1,800 sq ft), private enterprises with more than 20 workers or more than 150,000 litas of gross receipts were nationalized.[12] This disruption in management and operations created a sharp drop in production. Russian soldiers and officials were eager to spend their appreciated rubles and caused massive shortages of goods.[13] To turn small peasants against large landowners, collectivization was not introduced in Lithuania. All land was nationalized, farms were reduced to 30 hectares (74 acres), and extra land (some 575,000 hectares (5,750 km2)) was distributed to small farmers.[14] In preparation for eventual collectivization, new taxes between 30% and 50% of farm production were enacted.[11] The Lithuanian litas was artificially depreciated to 3–4 times its actual value and withdrawn by March 1941.[14] Before the elections to the People's Parliament, the Soviets arrested some 2,000 prominent political activists.[13] These arrests paralyzed any attempts to create anti-Soviet groups. An estimated 12,000 were imprisoned as "enemies of the people."[13] When farmers were unable to meet exorbitant new taxes, some 1,100 of the larger farmers were put on trial.[15] On June 14–18, 1941, less than a week before Germany's invasion, some 17,000 Lithuanians were deported to Siberia, where many perished due to inhumane living conditions (see June deportation).[16][17] Some of the many political prisoners were massacred by the retreating Red Army. These persecutions were key in soliciting support for the Nazis.

German invasion and Lithuanian revolt

[edit]

On June 22, 1941, the territory of the Lithuanian SSR was invaded by two advancing German army groups: Army Group North, which took over western and northern Lithuania, and Army Group Centre, which took over most of the Vilnius Region. The first attacks were carried out by the Luftwaffe against Lithuanian cities and claimed lives of some 4,000 civilians.[19] Most Russian aircraft were destroyed on the ground. Germans rapidly advanced, encountering only sporadic resistance from the Soviets and help from Lithuanians, who saw them as liberators and hoped that the Germans would re-establish their independence or at least autonomy.[citation needed]

Lithuanians took up arms against the Soviet for independence. Groups of men took control of strategic objects such as railroads, bridges, communication equipment and food warehouses, protecting them from potential scorched earth tactics. Kazys Škirpa, founder of LAF, had been preparing for the uprising since at least March 1941. The activists proclaimed Lithuanian independence and established the Provisional Government of Lithuania on June 23. Vilnius was taken by soldiers of the 29th Lithuanian Territorial Corps, many of them deserters from the Red Army, which had gang-pressed them when Lithuania and the Lithuanian Army changed hands. Smaller, less organized groups emerged in other cities and in the countryside.

The Battle of Raseiniai began June 23 as Soviets attempted to mount a counterattack, reinforced by tanks, but were overpowered by the 27th.[20] It is estimated that the uprising involved some 16,000[21] to 30,000 people and claimed lives of about 600 Lithuanians[21] and 5,000 Soviet activists. On June 24, Germans entered both Kaunas and Vilnius without a fight.[22] Within a week, the Germans had sustained 3,362 losses, but controlled the entire country.[23]

German occupation

[edit]Administration

[edit]

During the first days of war, German military administration, chiefly concerned with the region's security, tolerated Lithuanian attempts to establish their own administrative institutions and left a number of civilian issues to the Lithuanians. The Provisional Government in Kaunas attempted to establish the proclaimed independence of Lithuania and undo the damage of the one-year Soviet regime. During the six weeks of its existence, the Government issued about 100 laws and decrees, but they were largely not enforced. Its policies can be described as both anti-Soviet and antisemitic.[citation needed] The government organized volunteer forces, known as the Tautinio Darbo Apsaugos Batalionas (TDA), to serve as a basis for the re-established Lithuanian Army, but the battalion was soon employed by the Einsatzkommando 3 and Rollkommando Hamann for mass executions of the Lithuanian Jews in the Ninth Fort. At the time a rogue unit led by the infamous Algirdas Klimaitis rampaged through the city and the outskirts.[citation needed]

The Germans did not recognize the Lithuanian government, and at the end of July formed their own civil administration, part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland, which was divided into four Generalbezirke (General Districts). Adrian von Renteln became the Generalkommisssar of Generalbezirk Litauen and took over all government functions in Lithuania. The Provisional Government resigned on August 5; some of its ministers became General Advisers (Lithuanian: generalinis tarėjas) in charge of local self-government. The Germans did not have enough manpower to staff local administration; therefore, most local offices were headed by the Lithuanians. Policy decisions would have been made by high-ranking Germans and actually implemented by low-ranking Lithuanians. The General Advisers were mostly a rubber stamp institution that the Germans used as a scapegoat for unpopular decisions. Three of the advisers resigned within months, and other four were deported to the Stutthof concentration camp when they protested several German policies. Overall, local self-government was quite developed in Lithuania and helped to sabotage or hinder several German initiatives, including raising a Waffen-SS unit or providing men for forced labor in Germany.[citation needed]

The Holocaust

[edit]

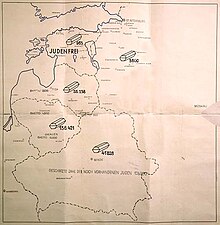

Before the Holocaust, Lithuania was home to about 210,000[24] or 250,000[25] Jews and was one of the greatest centers of Jewish theology, philosophy, and learning which preceded even the times of the Gaon of Vilna. The Holocaust in Lithuania can be divided into three stages: mass executions (June–December 1941), ghetto period (1942 – March 1943), and final liquidation (April 1943 – July 1944).

Unlike in other Nazi-occupied countries where the Holocaust was introduced gradually (first limiting Jewish civil rights, then concentrating Jews in ghettos, and only then executing them in death camps), executions in Lithuania started on the first days of war. Einsatzkommando A entered Lithuania one day behind the Wehrmacht invasion to encourage self-cleansing.[26]: 107 According to German documents, on June 25–26, 1941, "about 1,500 Jews were eliminated by Lithuanian partisans. Many Jewish synagogues were set on fire; on the following nights another 2,300 were killed."[27] The killings provided justification for rounding up Jews and putting them in ghettos to "protect them", where by December 1941 in Kaunas, 15,000 remained, 22,000 having been executed.[26]: 110 The executions were carried out at three main groups: in Kaunas (Ninth Fort), in Vilnius (Ponary massacre), and in countryside (Rollkommando Hamann). In Lithuania, by 1 December 1941, over 120,000 Lithuanian Jews had been killed.[26]: 110 It is estimated that 80% of the Lithuanian Jews were killed before 1942,[28] many by or with the active participation of Lithuanians in units, such as Police Battalions.[26]: 148

The surviving 43,000 Jews were concentrated in the Vilnius, Kaunas, Šiauliai, and Švenčionys Ghettos and forced to work for the benefit of German military industry. On June 21, 1943, Heinrich Himmler issued an order to liquidate all ghettos and transfer the remaining Jews to concentration camps. Vilnius Ghetto was liquidated, while Kaunas and Šiauliai were turned into concentration camps and survived until July 1944.[29] Remaining Jews were sent to camps in Stutthof, Dachau, Auschwitz. Only about 2,000–3,000 of Lithuanian Jews were liberated from these camps.[29] More survived by withdrawing into Russia's interior before the war broke out or by escaping the ghettos and joining the Jewish partisans.

The genocide rate of Jews in Lithuania, up to 95–97%, was the highest in Europe. This was primarily due, with few notable exceptions, to widespread Lithuanian cooperation with the German authorities. Jews were widely blamed for the previous Soviet regime (see Jewish Bolshevism) and were resented for welcoming Soviet troops.[30] Targeted Nazi propaganda exploited the anti-Soviet sentiment and increased already existing, traditional anti-Semitism.[31]

Collaboration

[edit]

Lithuanians formed several units that actively assisted Germans:[32]

- Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions – 26 battalions with 12,000–13,000 men

- Lithuanian Construction Battalions – 5 battalions with 2,500 men

- Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force – 10,000–12,000 men

- Self-Defence units – 3,000 men

- Homeland Protection Detachment – 6,000 men

10 of the Lithuanian police battalions, working with the Nazi Einsatzkommando, were involved in mass killings, and are thought to have executed 78,000 individuals.[26]: 148

Many[vague] members of the Lithuanian construction units were asked to join the Waffen-SS, of whom up to 40% eventually did, although no Lithuanian national unit was ever formed under the Waffen-SS, and all volunteers served on an individual basis.[citation needed]

Resistance

[edit]

The majority of anti-Nazi resistance in Lithuania came from the Polish partisans and the Soviet partisans.[citation needed] Both began sabotage and guerrilla operations against German forces immediately after the Nazi invasion of 1941. The most important Polish resistance organization in Lithuania was, as elsewhere in occupied Poland, the Home Army (Armia Krajowa). The Polish commander of the Wilno (Vilnius) region was Aleksander Krzyżanowski.

The activities of Soviet partisans in Lithuania were partly coordinated by the Command of the Lithuanian Partisan Movement headed by Antanas Sniečkus and partly by the Central Command of the Partisan Movement of the USSR.[33]

Jewish partisans in Lithuania also fought against the Nazi occupation. In September 1943, the United Partisan Organization led by Abba Kovner, attempted to start an uprising in the Vilna Ghetto, and later engaged in sabotage and guerrilla operations against the Nazi occupation.[34][unreliable source?] In July 1944, as part of its Operation Tempest, the Polish Home Army launched Operation Ostra Brama in an attempt to recapture that city.[citation needed]

There was no significant violent resistance directed against the Nazis originating from the Lithuanian society. In 1943, several underground political groups united under the Supreme Committee for the Liberation of Lithuania (Vyriausias Lietuvos išlaisvinimo komitetas or VLIK). It became mostly active outside of Lithuania among emigrants and deportees, and was able to establish contacts in Western countries and get support for resistance operations inside Lithuania (see Operation Jungle). It persisted abroad for many years as one of the groups representing Lithuania in exile.[35][36]

In 1943, the Nazis attempted to raise a Waffen-SS division from the local population as they had in other countries, but widespread coordination between resistance groups led to a boycot. The Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force (Lietuvos vietinė rinktinė) was eventually formed in 1944 under Lithuanian command, but was disbanded by the Nazis only a few months later for refusing to obey orders.[37][38][39] In particular, the relations between Lithuanians and the Poles were poor. Pre-war tensions over the Vilnius Region resulted in a low-level conflict between Poles and Lithuanians.[40] Nazi-sponsored Lithuanian units, primarily the Lithuanian Secret Police,[40] were active in the region and assisted the Germans in repressing the Polish population. In autumn 1943, Armia Krajowa started retaliation operations against the Lithuanian units and killed hundreds of mostly Lithuanian policemen and other collaborators during the first half of 1944. The conflict culminated in the massacres of Polish and Lithuanian civilians in June 1944 in the Glitiškės (Glinciszki) and Dubingiai (Dubinki) massacres.

Soviet re-occupation, 1944

[edit]The Soviet Union reoccupied Lithuania as part of the Baltic Offensive in 1944, a two-fold military-political operation to rout German forces and "liberate the Soviet Baltic peoples"[41] beginning in summer 1944.

Demographic losses

[edit]Lithuania suffered significant losses in World War II and the first post-war decade. Historians attempted to quantify population losses and changes, but their task was complicated by the lack of precise and reliable data. There were no censuses taken between the 1923, when Lithuania had 2,028,971 residents,[42] and the Soviet census of 1959, when Lithuania had 2,711,400 residents.[43] Various authors provide different breakdowns but generally agree that the population losses between 1940 and 1953 were more than one million people, a third of the pre-war population.[44][45][46][47] The three largest categories of this number are:

- victims of the Holocaust

- victims of Soviet repressions

- refugees or repatriates.

| Period | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaitiekūnas (2006)[45] |

Truska (2005)[48] |

Damušis (1990)[49] |

Zundė (1964)[47] | |

| First Soviet occupation (June 1940 – June 1941) |

161,000 | 76,000 | 135,600 | 93,200 |

| Nazi occupation (June 1941 – January 1945) |

464,600 | 504,000 | 330,000 | 373,800 |

| ⇨ Murdered during the Holocaust | 200,000 | 200,000 | 165,000 | 170,000 |

| ⇨ War refugees from Klaipėda Region | 150,000 | 140,000 | 120,000 | 105,000 |

| ⇨ War refugees from Lithuania | 60,000 | 64,000 | 60,000 | |

| ⇨ Other | 54,600 | 100,000 | 45,000 | 38,800 |

| Second Soviet occupation (January 1945 – 1953) |

530,000 | 486,000 | 656,800 | 530,000 |

| Total | 1,155,600 | 1,066,000 | 1,122,600 | 997,000 |

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Skirius (2002)

- ^ Clemens (2001), p. 6

- ^ Eidintas (1999), p. 170

- ^ Eidintas (1999), pp. 172–173

- ^ Gedye, G.E.R. (1939-10-03). "Latvia Gets Delay on Moscow Terms; Lithuania Summoned as Finland Awaits Call to Round Out Baltic 'Peace Bloc'". The New York Times: 1, 6.

- ^ Vardys (1997), p. 47

- ^ Sabaliūnas (1972), pp. 157–158

- ^ Rauch (2006), pp. 219–221

- ^ Vardys (1997), pp. 49–53

- ^ "The face of cruelty". VilNews. 2011.

- ^ a b Kamuntavičius (2001), pp. 408–409

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), pp. 116–117, 119

- ^ a b c Lane (2001), pp. 51–52

- ^ a b Anušauskas et al. (2005), pp. 120–121

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 123

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 140

- ^ Gurjanovas (1997)

- ^ "Killing Jews in the yard of NKVD garage in June 1941 (ex "Lietūkis")". Liutauras Ulevičius.

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 162

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 163

- ^ a b Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 171

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 165

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 164

- ^ MacQueen (1998)

- ^ Baumel & Laqueur (2001), pp. 51–52

- ^ a b c d e Buttar, Prit (21 May 2013). Between Giants. ISBN 9781780961637.

- ^ Einsatzgruppen Archives Archived 2008-10-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Porat (2002), p. 161

- ^ a b Bubnys (2004), pp. 216–218

- ^ Senn (Winter 2001)

- ^ Liekis (2002)

- ^ Stoliarovas (2008), pp. 15–16

- ^ Janavičienė (1997)

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Abba Kovner and Resistance in the Vilna Ghetto". About.com. Archived from the original on 2005-09-20. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- ^ Kaszeta (Fall 1988)

- ^ Banionis (2004)

- ^ Peterson (2001), p. 164

- ^ Lane (2001), p. 57

- ^ Mackevičius (Winter 1986)

- ^ a b Snyder (2003), p. 84

- ^ Muriev (1984), pp. 22–28

- ^ Eidintas (1999), p. 45

- ^ Vaitiekūnas (2006), p. 150

- ^ Anušauskas et al. (2005), p. 395

- ^ a b Vaitiekūnas (2006), p. 143

- ^ Damušis (1990), p. 30

- ^ a b Zundė (1964)

- ^ Anušauskas et al.

(2005), pp. 388–395 - ^ Damušis (1990), pp. 25–26

- Bibliography

- Anušauskas, Arvydas; Bubnys, Arūnas; Kuodytė, Dialia; Jakubčionis, Algirdas; Titinis, Vytautas; Truska, Liudas, eds. (2005). Lietuva, 1940–1990 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. ISBN 9986-757-65-7.

- Banionis, Juozas (2004). "Lietuvos laisvinimo veikla Vakaruose įsigalint detantui 1970–1974 m." Genocidas Ir Rezistencija (in Lithuanian). 15. ISSN 1392-3463.

- Baumel, Judith Tydor; Laqueur, Walter (2001). "Baltic Countries". The Holocaust Encyclopedia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08432-3.

- Bubnys, Arūnas (2004). "The Holocaust in Lithuania: An Outline of Major Stages and Their Results". In Nikžentaitis, Alvydas; Schreiner, Stefan; Staliūnas, Darius (eds.). The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-0850-4.

- Clemens, Walter C. (2001). The Baltic Transformed: Complexity Theory and European Security. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9859-9.

- Damušis, Adolfas (1990). Lietuvos gyventojų aukos ir nuostoliai Antrojo pasaulinio karo ir pokario 1940—1959 metais (in Lithuanian) (2nd ed.).

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Žalys, Vytautas; Senn, Alfred Erich (1999). Tuskenis, Edvardas (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Gurjanovas, Aleksandras (1997). "Gyventojų trėmimo į SSRS gilumą mastas (1941 m. gegužės–birželio mėn.)". Genocidas Ir Resistencija (in Lithuanian). 2. ISSN 1392-3463.

- Janavičienė, Audronė (1997). "Sovietiniai diversantai Lietuvoje (1941–1944)". Genocidas Ir Rezistencija (in Lithuanian). 1. ISSN 1392-3463.

- Kamuntavičius, Rūstis; Kamuntavičienė, Vaida; Civinskas, Remigijus; Antanaitis, Kastytis (2001). Lietuvos istorija 11–12 klasėms (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vaga. ISBN 5-415-01502-7.

- Kaszeta, Daniel J. (1988). "Lithuanian Resistance to Foreign Occupation 1940-1952". Lituanus. 3 (34). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Lane, Thomas (2001). Lithuania: Stepping Westward. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26731-5.

- Liekis, Šarūnas (2002). "Žydai: "kaimynai" ar "svetimieji"? Etninių mažumų problematika". Genocidas Ir Rezistencija (in Lithuanian). 12. ISSN 1392-3463.

- Mackevičius, Mečislovas (Winter 1986). "Lithuanian resistance to German mobilization attempts 1941-1944". Lituanus. 4 (32). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2019-08-05. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- MacQueen, Michael (1998). "The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 12 (1): 27–48. doi:10.1093/hgs/12.1.27.

- Muriyev, Dado (1984). "Preparations, Conduct of 1944 Baltic Operation Described". Military History Journal. 9. Joint Publications Research Service.[dead link]

- Peterson, Roger D. (2001). Resistance and Rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77000-9.

- Porat, Dina (2002). "The Holocaust in Lithuania: Some Unique Aspects". In Cesarani, David (ed.). The Final Solution: Origins and Implementation. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15232-1.

- Rauch, Georg von (2006). The Baltic States: The Years of Independence 1917–1940. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 1-85065-233-3.

- Sabaliūnas, Leonas (1972). Lithuania in Crisis: Nationalism to Communism 1939–1940. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33600-7.

- Senn, Alfred E. (Winter 2001). "Reflections on the Holocaust in Lithuania: A New Book by Alfonsas Eidintas". Lituanus. 4 (47). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Skirius, Juozas (2002). "Klaipėdos krašto aneksija 1939–1940 m.". Gimtoji istorija. Nuo 7 iki 12 klasės (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Elektroninės leidybos namai. ISBN 9986-9216-9-4. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- Stoliarovas, Andriejus (2008). Lietuvių pagalbinės policijos (apsaugos) 12-asis batalionas (Thesis) (in Lithuanian). Vytautas Magnus University.

- Snyder, Timothy (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- Vaitiekūnas, Stasys (2006). Lietuvos gyventojai: Per du tūkstantmečius (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. ISBN 5-420-01585-4.

- Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Sedaitis, Judith B. (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. WestviewPress. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- Zundė, Pranas (1964). "Lietuvos gyventojų dinamika ir struktūra". Aidai (in Lithuanian). 10. ISSN 0002-208X.

- Secondary sources believed to meet Eastern Europe criteria

- Sužiedelis, Saulius (2006). "Lithuanian Collaboration during the Second World War: Past Realities, Present Perceptions: Collaboration and Resistance during the Holocaust: Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". The Mass Persecution and Murder of Jews: The Summer and Fall of. Vol. 158.2004. University of California Press. pp. 313–359. ISBN 978-0-520-02600-1.

This presentation is in part a modified summary and collation of my studies presented in earlier venues: *;My reports **Foreign Saviors, Native Disciples: Perspectives on Collaboration in Lithuania, 1940–1945, presented in April 2002 at the "Reichskommissariat Ostland" conference at Uppsala University and Södertörn University College, now published in: Collaboration and Resistance during the Holocaust. Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, ed. David Gaunt et al *;My articles in Vilnius at the conference Holocaust in Lithuania in Vilnius 2002: **The Burden of 1941, in: 'Lituanus' 47:4 (2001), pp. 47-60; **Thoughts on Lithuania's Shadows of the Past: A Historical Essay on the Legacy of War, Part I, in: 'Vilnius (Summer 1998), pp. 129-146; **Thoughts on Lithuania's Shadows of the Past: A Historical Essay on the Legacy of War, Part II, in: 'Vilnius' (Summer 1999), pp. 177-208...

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (2007). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947 (illustrated ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786429134. ** despite the title, this source contains several substantive mentions of Lithuania's circumstances. While Lithuania is not its primary topic, the histories of the two countries are closely interrelated and the mentions are well beyond passing references; several are three or more pages long

- Full text available online

- Dov Levin (2000). The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews in Lithuania - Berghahn Series (illustrated ed.). Berghahn Books. p. 283. doi:10.1163/9789401208895_005. ISBN 9653080849.

- Gruodyte, Edita; Adomaityte, Aurelija. "The Tragedy of the Holocaust in Lithuania: From the Roots of the Identity to the Efforts towards Reconciliation" (PDF). repozytorium.uni.pl.

Criterion problems

[edit]- Sužiedelis, Saulius. "341. The Perception of the Holocaust: Public Challenges and Experience in Lithuania". Wilson Center.

- I believe the Wilson Center is considered "a reputable institution" if not though, this may well qualify as written by an expert

- June 1999 United States Justice Department

- I believe the US Justice Department is considered "a reputable institution" if not though, this may well qualify as written by an expert since afaik it concerns their litigation

- Malinauskaite. "Holocaust Memory and Antisemitism in Lithuania: Reversed Memories of the Second World War" (PDF).

- Malinauskaitė, Gintarė (2019). Mediated Memories: Narratives and Iconographies of the Holocaust in Lithuania. Marburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sužiedėlis, Saulius (2006). "Lithuanian Collaboration during the Second World War: Past Realities, Present Perceptions". In Tauber, Joachim (ed.). "Kollaboration" in Nordosteuropa: Erscheinungsformen und Deutungen im 20. Jahrhundert (PDF). Wiesbaden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sužiedėlis, Simas, ed. (1970–1978). "Juozas Brazaitis". Encyclopedia Lituanica. Vol. I. Boston, Massachusetts: Juozas Kapočius. pp. 396–397. LCCN 74-114275.

- Wnuk, Rafał (2018). Leśni bracia. Podziemie antykomunistyczne na Litwie, Łotwie i w Estonii 1944-1956 [Forest Brothers. Anti-communist underground in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia 1944-1956] (in Polish). Lublin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Woolfson, Shivaun (2014). Holocaust Legacy in Post-Soviet Lithuania. People, Places and Objects. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Vareikis, Vygantas (2009). "In the Shadow of the Holocaust: Lithuanian-Jewish Relations in the Crucial Years 1940-1944". In Bankier, David; Gutman, Israel (eds.). Nazi Europe and the Final Solution. Yad Vashem. ISBN 978-1-84545-410-4.

- Veilentienė, Audronė (2016). "Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas nacių okupacijos metais ir antinacinė rezistencija" [Vytautas Magnus University during the Nazi Occupation and Anti-Nazi Resistance]. Kauno istorijos metraštis. 16: 195–217. doi:10.7220/2335-8734.16.8.