Gods' Man

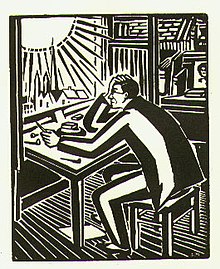

Gods' Man is a wordless novel by American artist Lynd Ward (1905–1985) published in 1929. In 139 captionless woodblock prints, it tells the Faustian story of an artist who signs away his soul for a magic paintbrush. Gods' Man was the first American wordless novel, and is considered a precursor of the graphic novel, whose development it influenced.

Ward first encountered the wordless novel with Frans Masereel's The Sun (1919) while studying art in Germany in 1926. He returned to the United States in 1927 and established a career for himself as an illustrator. He found Otto Nückel's wordless novel Destiny (1926) in New York City in 1929, and it inspired him to create such a work of his own. Gods' Man appeared a week before the Wall Street Crash of 1929; it nevertheless enjoyed strong sales and remains the best-selling American wordless novel. Its success inspired other Americans to experiment with the medium, including cartoonist Milt Gross, who parodied Gods' Man in He Done Her Wrong (1930). In the 1970s Ward's example inspired cartoonists Art Spiegelman and Will Eisner to create their first graphic novels.

Content

The wordless novel Gods' Man is a silent narrative made up of prints of 139 engraved woodblocks.[1] Each image moves the story forward by an interval Ward chooses to maintain story flow.[2] Ward wrote in Storyteller Without Words (1974) that too great an interval would put too much interpretational burden on the reader, while too little would make the story tedious. Wordless novel historian David A. Beronä likens these concerns with the storytelling methods of comics.[2]

The artwork is executed in black and white; the images vary in size and dimension, up to 6 by 4 inches (15 cm × 10 cm), the size of the opening and closing images of each chapter. Ward uses symbolic contrast of dark and light to emphasize the corruption of the city, where even in daylight the buildings darken the skies; in the countryside, the scenes are bathed in natural light.[3] Ward exaggerates facial expression to convey emotion without resorting to words. Composition also conveys emotion: in the midst of his fame, an image has the artist framed by raised wineglasses; the faces of those holding the glasses are not depicted, highlighting the isolation the artist feels.[3] The story parallels the Faust theme, and the artwork and execution show the influence of film, in particular those of German studio Ufa.[4]

The placement of the apostrophe in the title Gods' Man implies a plurality of gods, rather than Judeo-Christianity's monotheistic God.[5] It alludes to a line from the play Bacchides by ancient Roman playwright Plautus: "He whom the gods favor, dies young."[a][6]

Plot synopsis

A poor artist signs a contract with a masked stranger, who gives him a magic brush, with which the artist rapidly rises in the art world.[7] He is disillusioned when he discovers the world is corrupted by money, personified by his mistress. He wanders around the city, seeing his auctioneer and mistress in everyone he sees. Enraged by the hallucinations, he attacks one of them, who turns out to be a police officer. The artist is jailed for it, but he escapes, and a mob chases him from the city. He is injured when he jumps into a ravine to avoid recapture. A woman who lives in the woods discovers him and brings him back to health. They have a child, and live a simple, happy life together, until the mysterious stranger returns and beckons the artist to the edge of a cliff. The artist prepares to paint a portrait of the stranger but fatally falls from the cliff with fright when the stranger reveals a skull-like head behind the mask.[8]

Background

Chicago-born[9] Lynd Ward (1905–1985) was a son of Methodist minister Harry F. Ward (1873–1966), a social activist and the first chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union. Throughout his career, Ward displayed in his work the influence of his father's interest in social injustice.[10] He was early drawn to art, and decided to become an artist when his first-grade teacher told him that "Ward" spelled backward was "draw".[11] He excelled as a student, and contributed art and text to high school and college newspapers.[12]

In 1926, after graduating from Teachers College, Columbia University, Ward married writer May McNeer and the couple left for an extended honeymoon in Europe[13].[14] After four months in eastern Europe, the couple settled in Leipzig in Germany, where, as a special one-year student at the National Academy of Graphic Arts and Bookmaking,[b], Ward studied wood engraving. There he encountered German Expressionist art, and read the wordless novel The Sun[c] (1919),a modernized version of the story of Icarus, told in sixty-three wordless woodcut prints, by Flemish woodcut artist Frans Masereel (1889–1972).[14]

Ward returned to the United States in 1927, and freelanced his illustrations. In 1929, he came across German artist Otto Nückel's wordless novel Destiny[d] (1926) in New York City.[15] Nückel's only work in the genre, Destiny told of the life and death of a prostitute in a style inspired by Masereel's, but with a greater cinematic flow.[14] The work inspired Ward to create a wordless novel of his own,[15] whose story sprang from his "youthful brooding" on the short, tragic lives of artists such as Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Keats, and Shelley; Ward's argument in the work was "that creative talent is the result of a bargain in which the chance to create is exchanged for the blind promise of an early grave".[16]

Publication history

In March 1929 Ward showed the first thirty blocks to Harrison Smith (1888–1971)[17] of the publisher Cape & Smith. Smith offered him a contract and told him the work would be the lead title in the company's first catalog[e] if Ward could finish it by the summer's end. The first printing appeared that October;[18] it had trade and deluxe editions.[18] The trade edition was printed from electrotype plates made from molds of the original boxwood woodblocks; the deluxe edition was printed from the original woodblocks themselves, and was a signed edition limited to 409 copies, printed on acid-free paper, bound in black cloth, and sheathed in a slipcase.[19] The pages were printed on the recto face of the page; the verso was left blank.[20] It was dedicated to three of Ward's teachers: his wood engraving teacher in Leipzig, Hans Alexander "Theodore" Mueller (1888–1962), and Teachers College, Columbia University art instructors John P. Heins (1896–1969) and Albert C. Heckman (1893–1971).[21]

The book has been reprinted and anthologized in a variety of editions.[22] In 1974, it appeared in Storyteller Without Words, a collected edition with Madman's Drum (1930) and Wild Pilgrimage (1932) prefaced with essays by Ward.[23] The stories appeared in a compact fashion, sometimes four images to a page.[20] In 2010, it was collected with Ward's other five wordless novels in a two-volume Library of America edition edited by cartoonist Art Spiegelman.[22]

The book's original woodblocks are kept in the Lynd Ward Collection in the Joseph Mark Lauinger Memorial Library at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.,[19] bequeathed by Ward's daughters Nanda and Robin.[24]

Reception and legacy

Gods' Man was the first American wordless novel,[7] and no such European work had yet been published in the US.[10] Gods' Man proved to be the best selling.[7] Though it was released the week before the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that ensued,[18] it went through three printings by January 1930,[25] and sold more than 20,000 copies in six printings over its first four years.[10] During the same period, the young Ward saw his career as an in-demand book illustrator bloom, and found acceptance as an authority on children's book illustration.[16]

The success of Gods' Man led to the American publication of Nückel's Destiny in 1930.[26] In 1930 cartoonist Milt Gross parodied Gods' Man and silent melodrama films in a wordless novel of his own, He Done Her Wrong, subtitled "The Great American Novel, and not a word in it—no music too".[27] The protagonist is a lumberjack, a commentary on Ward as a woodcut artist.[28]

The Ballet Theatre of New York considered an adaptation of Gods' Man, and a board member approached Felix R. Labunski to compose it. Financial difficulties moved Labunski to abandon it and his other creative work.[29] Despite several proposals made through the 1960s, no film adaptation has been made of Gods' Man.[30]

Left-leaning artists and writers admired the book, and Ward frequently received poetry based on it. Allen Ginsberg used imagery from Gods' Man in his poem Howl (1956),[31][f] and referred to the images of the city and jail in Ward's book in the poem's annotations.[2] Abstract expressionist painter Paul Jenkins wrote Ward in 1981 of the influence the book's "energy and unprecedented originality" had on his own art.[31] In 1973[32] Art Spiegelman created the four-page comic strip "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" about his mother's suicide,[33] executed in an Expressionist woodcut style inspired by Ward's work.[34] Spiegelman later incorporated the strip into his graphic novel Maus.[32] My Morning Jacket frontman Jim James released a solo album Regions of Light and Sound of God in 2013 inspired by Gods' Man, which he had at first conceived as a soundtrack to a film adaptation of the book.[35]

Gods' Man remains Ward's best known and most widely read wordless novel. Spiegelman considered this due less to the qualities of the book per se in relation to Ward's other wordless novels as to the book's novelty as the first wordless novel published in the US.[36] Irwin Haas praised the artwork but found the storytelling uneven, and thought that only with his third wordless novel Wild Pilgrimage did Ward come to master the medium.[37]

The artwork has drawn some unintended mirth: American writer Susan Sontag included it on her "canon of Camp" in her 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'",[38] and Spiegelman admitted that the scenes of "the depiction of Our Hero idyllically skipping through the glen with the Wife and their child makes [him] snicker".[39]

Psychiatrist M. Scott Peck objected strongly to the content of the book: he believed it had a destructive effect on children, and called it "the darkest, ugliest book [he] had ever seen".[40] To Peck, the mysterious stranger represented Satan and the spirit of death.[41]

Notes

- ^ "Template:Lang-la", Bacchides, IV.vii

- ^ Template:Lang-de[13]

- ^ Template:Lang-de

- ^ Template:Lang-de

- ^ This catalog also featured the original edition of The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner.[17]

- ^ In Part II, lines 82–84.[31]

References

- ^ Spiegelman 2010a, p. xi.

- ^ a b c Beronä 2008, p. 42.

- ^ a b Beronä 2008, pp. 42, 44.

- ^ E. P. 1930, p. 328.

- ^ Peck 2005, p. 216.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010d, p. 828.

- ^ a b c Spiegelman 2010a, p. xii.

- ^ Beronä 2008, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010b, p. 799.

- ^ a b c Beronä 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010b, p. 801.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 802–803.

- ^ a b Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 803–804.

- ^ a b c Spiegelman 2010a, p. x.

- ^ a b Spiegelman 2010b, pp. 804–805.

- ^ a b Painter 1962, p. 664.

- ^ a b Spiegelman 2010d, p. 833.

- ^ a b c Spiegelman 2010b, p. 805.

- ^ a b Spiegelman 2010c, p. 823.

- ^ a b Kelley 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010d, pp. 828–829.

- ^ a b Bulson 2011.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010c, p. 825.

- ^ Smykla 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Walker 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010d, pp. 832–833.

- ^ Spiegelman 2010a, pp. xiii–xiv.

- ^ Kelman 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Beronä 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Willett 2005, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Beronä 2003, p. 66.

- ^ a b Witek 1989, p. 98.

- ^ Rothberg 2000, p. 214.

- ^ Witek 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Zemler 2013.

- ^ Kelley 2010, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Haas 1937, p. 84–86.

- ^ Wolk 2011; Sontag 1999, p. 55.

- ^ Wolk 2011.

- ^ Peck 2005, p. 215.

- ^ Peck 2005, p. 189.

Works cited

Books

- Beronä, David A. (2008). Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9469-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelman, Ari Y. (2010). "Introduction: Geeve a Listen". Is Diss a System?: A Milt Gross Comic Reader. New York University Press. pp. 1–54. ISBN 978-0-8147-4837-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peck, M. Scott (2005). Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-7654-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rothberg, Michael (2000). Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3459-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smykla, Evelyn Ortiz (1999). Marketing and Public Relations Activities in ARL Libraries: A SPEC Kit. Association of Research Libraries. UOM:39015042082936.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sontag, Susan (1999). Cleto, Fabio (ed.). Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject : a Reader. University of Michigan Press. pp. 53–65. ISBN 978-0-472-06722-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Reading Pictures". In Spiegelman, Art (ed.). Lynd Ward: Gods' Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. ix–xxv. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Chronology". In Spiegelman, Art (ed.). Lynd Ward: Gods' Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 799–821. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Note on the Texts". In Spiegelman, Art (ed.). Lynd Ward: Gods' Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 823–825. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Notes". In Spiegelman, Art (ed.). Lynd Ward: Gods' Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 827–833. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.

- Willett, Perry (2005). "The Cutting Edge of German Expressionism: The Woodcut Novel of Frans Masereel and Its Influences". In Donahue, Neil H. (ed.). A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. Camden House Publishing. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-57113-175-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker, George, ed. (2007). Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-270-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Witek, Joseph (1989). Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0-87805-406-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Journals and magazines

- Beronä, David A. (March 2003). "Wordless Novels in Woodcuts". Print Quarterly. 20 (1). Print Quarterly Publications: 61–73. JSTOR 41826477.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - E. P. (June 1930). "God's Man. A Novel in Woodcuts by Lynd Ward". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 56 (327). The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.: 327–328. JSTOR 864362.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haas, Irvin (May 1937). "A Bibliography of the Work of Lynd Ward". Prints. 7 (8). Connoisseur Publications: 84–86.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Painter, Helen W. (November 1962). "Lynd Ward: Artist, Writer, and Scholar". Elementary English. 39 (7). National Council of Teachers of English: 663–671.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Witek, Joseph (2004). "Imagetext, or, Why Art Spiegelman Doesn't Draw Comics". ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. 1 (1). University of Florida. ISSN 1549-6732. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Web

- Bulson, Eric (2011-12-14). "A Great, Wordless, American Storyteller". The Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelley, Rich (2010). "The Library of America interviews Art Spiegelman about Lynd Ward" (PDF). Library of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolk, Douglas (2011-02-04). "Emanata: Novels in Woodcuts, Comics in Words". Time. Archived from the original on 2011-02-07. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zemler, Emily (2013-04-04). "How a Wordless 1929 Novel Inspired Jim James' Solo Album". MTV Hive. Archived from the original on 2013-04-06. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Joseph Mark Lauinger Memorial Library at Georgetown University, where the original woodblocks for Gods' Man are kept

- Boxer, Sarah (2010-10-17). "America's First Wordless Novelist". Slate. Retrieved 2013-03-18.