Granuloma

| Granuloma | |

|---|---|

| |

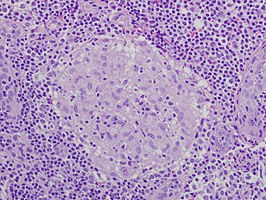

| Picture of a granuloma (without necrosis) as seen through a microscope on a glass slide: The tissue on the slide is stained with two standard dyes (hematoxylin: blue, eosin: pink) to make it visible. The granuloma in this picture was found in a lymph node of a patient with a Mycobacterium avium infection. | |

| Specialty | Pathology |

A granuloma is an aggregation of macrophages that forms in response to chronic inflammation. This occurs when the immune system attempts to isolate foreign substances that it is otherwise unable to eliminate.[1] Such substances include infectious organisms including bacteria and fungi, as well as other materials such as foreign objects, keratin, and suture fragments.[2][3][4][5]

Definition

In pathology, a granuloma is an organized collection of macrophages.[1][6]

In medical practice, doctors occasionally use the term granuloma in its more literal meaning: "a small nodule". Since a small nodule can represent any tissue from a harmless nevus to a malignant tumor, this use of the term is not very specific. Examples of this use of the term granuloma are the lesions known as vocal cord granuloma (known as contact granuloma), pyogenic granuloma, and intubation granuloma, all of which are examples of granulation tissue, not granulomas. "Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma" is a lesion characterized by keloid-like fibrosis in the lung and is not granulomatous. Similarly, radiologists often use the term granuloma when they see a calcified nodule on X-ray or CT scan of the chest. They make this assumption since granulomas usually contain calcium, although the cells that form a granuloma are too tiny to be seen by a radiologist. The most accurate use of the term granuloma requires a pathologist to examine surgically removed and specially colored (stained) tissue under a microscope.

Histiocytes (specifically macrophages) are the cells that define a granuloma. They often fuse to form multinucleated giant cells (Langhans giant cell).[7] The macrophages in granulomas are often referred to as "epithelioid". This term refers to the vague resemblance of these macrophages to epithelial cells. Epithelioid macrophages differ from ordinary macrophages in that they have elongated nuclei that often resemble the sole of a slipper or shoe. They also have larger nuclei than ordinary macrophages, and their cytoplasm is typically pinker when stained with eosin. These changes are thought to be a consequence of "activation" of the macrophage by the offending antigen.[citation needed]

The other key term in the above definition is the word "organized" which refers to a tight, ball-like formation. The macrophages in these formations are typically so tightly clustered that the borders of individual cells are difficult to appreciate. Loosely dispersed macrophages are not considered to be granulomas.

All granulomas, regardless of cause, may contain additional cells and matrix. These include lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, multinucleated giant cells, fibroblasts, and collagen (fibrosis). The additional cells are sometimes a clue to the cause of the granuloma. For example, granulomas with numerous eosinophils may be a clue to coccidioidomycosis or allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease, and granulomas with numerous neutrophils suggest blastomycosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, aspiration pneumonia, or cat-scratch disease.

In terms of the underlying cause, the difference between granulomas and other types of inflammation is that granulomas form in response to antigens that are resistant to "first-responder" inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and eosinophils. The antigen causing the formation of a granuloma is most often an infectious pathogen or a substance foreign to the body, but sometimes the offending antigen is unknown (as in sarcoidosis).[citation needed]

Granulomas are seen in a wide variety of diseases, both infectious and noninfectious.[2][3] Infections characterized by granulomas include tuberculosis, leprosy, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and cat-scratch disease. Examples of noninfectious granulomatous diseases are sarcoidosis, Crohn's disease, berylliosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, pulmonary rheumatoid nodules, and aspiration of food and other particulate material into the lung.

An important feature of granulomas is whether or not they contain necrosis, which refers to dead cells that, under the microscope, appear as a mass of formless debris with no nuclei present. A related term, caseation (literally: turning to cheese) refers to a form of necrosis that, to the unaided eye, appears cheese-like ("caseous"), and is typically a feature of the granulomas of tuberculosis. The identification of necrosis in granulomas is important because granulomas with necrosis tend to have infectious causes.[2] Several exceptions to this general rule exist, but it nevertheless remains useful in day-to-day diagnostic pathology.

- Necrosis in granulomas

-

Granuloma without necrosis in a lymph node of a person with sarcoidosis

-

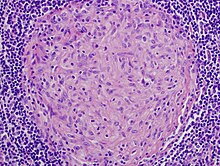

Granuloma with central necrosis in a lung of a person with tuberculosis: Note the Langhans-type giant cells (with many nuclei arranged in a horseshoe-like pattern at the edge of the cell) around the periphery of the granuloma. Langhans-type giant cells are seen in many types of granulomas and are not specific for tuberculosis.

Diseases with granulomas

Tuberculosis

The granulomas of tuberculosis tend to contain necrosis ("caseating tubercules"), but non-necrotizing granulomas may also be present.[8] Multinucleated giant cells with nuclei arranged like a horseshoe (Langhans giant cell) and foreign body giant cells[9] are often present, but are not specific for tuberculosis. A definitive diagnosis of tuberculosis requires identification of the causative organism by microbiologic cultures.[10]

Leprosy

In leprosy, granulomas are found in the skin and tend to involve nerves. The appearance of the granulomas differs according to the precise type of leprosy.

Schistosomiasis

Some schistosome ova that are laid in intestinal and urinary venules backwash into the liver via the portal vein, causing granuloma formation in the liver.

Histoplasmosis

Granulomas are seen in most forms of histoplasmosis (acute histoplasmosis, histoplasmoma, chronic histoplasmosis). Histoplasma organisms can sometimes be demonstrated within the granulomas by biopsy or microbiological cultures.[2]

Cryptococcosis

When Cryptococcus infection occurs in persons whose immune systems are intact, granulomatous inflammation is typically encountered. The granulomas can be necrotizing or non-necrotizing. Using a microscope and appropriate stains, organisms can be seen within the granulomas.[10]

Cat-scratch disease

Cat-scratch disease is an infection caused by the bacterial organism Bartonella henselae, typically acquired by a scratch from a kitten infected with the organism. The granulomas in this disease are found in the lymph nodes draining the site of the scratch. They are characteristically "suppurative", i.e., pus-forming, containing large numbers of neutrophils. Organisms are usually difficult to find within the granulomas using methods routinely used in pathology laboratories.

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is a systemic disease affecting the periarteriolar connective tissue and can occur after an untreated group A, beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngeal infection. It is believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a disease of unknown cause characterized by non-necrotizing ("non-caseating") granulomas in multiple organs and body sites,[11] most commonly the lungs and lymph nodes within the chest cavity. Other common sites of involvement include the liver, spleen, skin, and eyes. The granulomas of sarcoidosis are similar to those of tuberculosis and other infectious granulomatous diseases. In most cases of sarcoidosis, though, the granulomas do not contain necrosis and are surrounded by concentric scar tissue (fibrosis). Sarcoid granulomas often contain star-shaped structures called asteroid bodies or lamellar structures termed Schaumann bodies, but these structures are not specific for sarcoidosis.[10] Sarcoid granulomas can resolve spontaneously without complications or heal with residual scarring. In the lungs, this scarring can cause a condition known as pulmonary fibrosis that impairs breathing. In the heart, it can lead to rhythm disturbances, heart failure, and even death.

Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is an inflammatory condition of uncertain cause characterized by severe inflammation in the wall of the intestines and other parts of the abdomen. Within the inflammation in the gut wall, granulomas are often found and are a clue to the diagnosis.[12]

Listeria monocytogenes

Listeria monocytogenes infection in infants can cause potentially fatal disseminated granulomas, called granulomatosis infantiseptica, following in utero infection.

Leishmania spp.

Leishmaniases are a group of human diseases caused by Leishmania genus and transmitted by a sandfly bite can lead to granulomatous inflammation[13] in skin (cutaneous form of the disease) and liver (visceral form), with research suggesting effective granuloma formation to be desirable in the resolution of the disease.[14]

Pneumocystis pneumonia

Pneumocystis infection in the lungs is usually not associated with granulomas, but rare cases are well documented to cause granulomatous inflammation. The diagnosis is established by finding Pneumocystis yeasts within the granulomas on lung biopsies.[15]

Aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is typically caused by aspiration of bacteria from the oral cavity into the lungs, and does not result in the formation of granulomas. Granulomas may form, though, when food particles or other particulate substances such as pill fragments are aspirated into the lungs. Patients typically aspirate food because they have esophageal, gastric, or neurologic problems. Intake of drugs that depress neurologic function may also lead to aspiration. The resultant granulomas are typically found around the airways (bronchioles), and are often accompanied by foreign body-type, multinucleated giant cells, acute inflammation, or organizing pneumonia. The finding of food particles in lung biopsies is diagnostic.[16]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Necrotizing granulomas can develop in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, typically manifesting as bumps in the soft tissues around the joints (so-called rheumatoid nodules) or in the lungs.[10]

Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare is a skin disease of unknown cause in which granulomas are found in the dermis of the skin, but it is not a true granuloma. Typically, a central zone of necrobiotic generation of collagen is seen, with surrounding inflammation and mucin deposition on pathology.

Foreign-body granuloma

A foreign-body granuloma occurs when a foreign body (such as a wood splinter, piece of metal, glass etc.) penetrates the body's soft tissue followed by acute inflammation and formation of a granuloma.[17] In some cases the foreign body can be found and removed even years after the precipitating event.[18]

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis

Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a rare granulomatous skin disorder of unknown cause. It is temporary and tends to affect children, usually of African descent.

Granulomas associated with vasculitis

Certain inflammatory diseases are characterised by a combination of granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels). Both the granulomas as well as the vasculitis tend to occur in association with necrosis. Classic examples of such diseases include granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Etymology

The term is from Latin grānulum 'small grain' and from Ancient Greek -μᾰ (-ma) 'disease'. The plural is granulomas or granulomata. The adjective granulomatous means "characterized by granulomas".

See also

- Lick granuloma, a skin disorder in dogs that results from dog's urge to lick the lower portion of its leg

- Sperm granuloma

- Contact granuloma, i.e. "throat granuloma"

References

- ^ a b Williams, Olivia; Fatima, Saira (5 April 2020). "Granuloma". StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119473. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Mukhopadhyay S, Farver CF, Vaszar LT, Dempsey OJ, Popper HH, Mani H, Capelozzi VL, Fukuoka J, Kerr KM, Zeren EH, Iyer VK, Tanaka T, Narde I, Nomikos A, Gumurdulu D, Arava S, Zander DS, Tazelaar HD (Jan 2012). "Causes of pulmonary granulomas: a retrospective study of 500 cases from seven countries". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 65 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200336. PMID 22011444. S2CID 28504428.

- ^ a b Woodard BH, Rosenberg SI, Farnham R, Adams DO (1982). "Incidence and nature of primary granulomatous inflammation in surgically removed material". American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 6 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1097/00000478-198203000-00004. PMID 7102892. S2CID 12907076.

- ^ Hunter DC, Logie JR (1988). "Suture granuloma". British Journal of Surgery. 75 (11): 1149–1150. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800751140. PMID 3208057. S2CID 12804852.

- ^ Chen KT, Kostich ND, Rosai J (1978). "Peritoneal foreign body granulomas to keratin in uterine adenocanthoma". Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 102 (4): 174–177. PMID 580709.

- ^ Adams DO (1976). "The granulomatous inflammatory response. A review". American Journal of Pathology. 84 (1): 164–191. PMC 2032357. PMID 937513.

- ^ Murphy, Kenneth; Paul, Travers; Mark, Walport (2008). Janeway's immunobiology (7th ed.). New York: Garland Science. p. 372. ISBN 978-0815341239.

- ^ Cohen, Sara B.; Gern, Benjamin H.; Urdahl, Kevin B. (2022-04-26). "The Tuberculous Granuloma and Preexisting Immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 40 (1): 589–614. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-093019-125148. ISSN 0732-0582. Archived from the original on 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ dental decks part II Edited by Nour

- ^ a b c d Mukhopadhyay S, Gal AA (2010). "Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis". Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 134 (5): 669–690. doi:10.5858/134.5.667. PMID 20441499. Archived from the original on 2022-06-01. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ^ Iannuzzi M, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS (2007). "Sarcoidosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (21): 2153–2165. doi:10.1056/NEJMra071714. PMID 18032765.

- ^ Cohen, Elizabeth (June 11, 2009). "Teen diagnoses her own disease in science class". CNN Health. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on June 16, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Ridley, M. J.; Ridley, D. S. (April 1986). "Monocyte recruitment, antigen degradation and localization in cutaneous leishmaniasis". British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 67 (2): 209–218. ISSN 0007-1021. PMC 2013155. PMID 3707851.

- ^ Kaye, Paul M.; Beattie, Lynette (2016-03-01). "Lessons from other diseases: granulomatous inflammation in leishmaniasis". Seminars in Immunopathology. 38 (2): 249–260. doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0548-7. ISSN 1863-2300. PMC 4779128. PMID 26678994.

- ^ Hartel PH, Shilo K, Klassen-Fischer M, et al. (2010). "Granulomatous reaction to Pneumocystis jirovecii. clinicopathologic review of 20 cases". American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 34 (5): 730–734. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9f16a. PMID 20414100. S2CID 25202257.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay S, Katzenstein AL (2007). "Pulmonary disease due to aspiration of food and other particulate matter: a clinicopathologic study of 59 cases diagnosed on biopsy or resection specimens". American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 31 (5): 752–759. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000213418.08009.f9. PMID 17460460. S2CID 45207101.

- ^ Joyce, S; Rao Sripathi, BH; Mampilly, MO; Firdoose Nyer, CS (September 2014). "Foreign Body Granuloma". J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 13 (3): 351–4. doi:10.1007/s12663-010-0113-9. PMC 4082545. PMID 25018614.

- ^ El Bouchti, I.; Ait Essi, F.; Abkari, I.; Latifi, M.; El Hassani, S. (2012). "Foreign Body Granuloma: A Diagnosis Not to Forget". Case Reports in Orthopedics. 2012. Hindawi Publishing Corporation: 1–2. doi:10.1155/2012/439836. PMC 3505897. PMID 23259122.