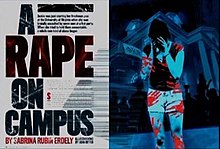

A Rape on Campus

| |

| Author | Sabrina Rubin Erdely |

|---|---|

| Subject | An alleged gang rape at a college fraternity |

| Set in | University of Virginia |

| Publisher | Rolling Stone |

Publication date |

|

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Magazine article |

"A Rape on Campus" is a retracted, defamatory Rolling Stone magazine article[2][3][4] written by Sabrina Erdely and originally published on November 19, 2014, that describes a purported group sexual assault at the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville, Virginia. Rolling Stone retracted the story in its entirety on April 5, 2015.[1][5] The article claimed that UVA student Jackie Coakley had been taken to a party hosted by UVA's Phi Kappa Psi fraternity by a fellow student and led to a bedroom to be gang raped by several fraternity members as part of a fraternity initiation ritual.

Jackie's account generated much media attention, and UVA President Teresa Sullivan suspended all fraternities. After other journalists investigated the article's claims and found significant discrepancies, Rolling Stone issued multiple apologies for the story. It has since been reported that Jackie may have invented portions of the story in an unsuccessful attempt to win the affections of a fellow student in whom she had a romantic interest.[6][7] In a deposition given in 2016, Jackie stated that she believed her story at the time.[8][9]

On January 12, 2015, Charlottesville Police officials told UVA that an investigation had failed to find any evidence confirming the events in the Rolling Stone article. UVA President Teresa Sullivan acknowledged that the story was discredited. Charlottesville Police officially suspended their four-month investigation on March 23, 2015, based on lack of credible evidence.[10] The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism audited the editorial processes that culminated in the article being published. On April 5, 2015, Rolling Stone retracted the article and published the independent report on the publication's history.[1]

UVA associate dean Nicole Eramo, the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity, and several fraternity members later filed lawsuits against Erdely and Rolling Stone. Eramo was awarded $3 million by a jury who concluded that Rolling Stone defamed her with actual malice,[11] and Rolling Stone settled the lawsuit with the fraternity for $1.65 million.[12]

Story

[edit]

On November 19, 2014, Rolling Stone published the now retracted article by Sabrina Erdely titled "A Rape on Campus" about an alleged gang rape of a University of Virginia (UVA) student, Jackie Coakley.[13][14] The UVA student, identified only as "Jackie" by the magazine, had been taken to a party by a fellow student, hosted at UVA's Phi Kappa Psi fraternity during 2012. At the chapter house party, Jackie alleged in the article, her date led her to a bedroom where she was gang raped by several fraternity members as part of their initiation ritual.[15] For anonymity, Erdely only used Jackie's first name and gave pseudonyms to other students discussed in the story.[16]

According to Los Angeles Times columnist Jonah Goldberg's summary of the story, on September 28, 2012, Jackie, a freshman at UVA, had a date with a Phi Kappa Psi member "Drew", a junior at UVA. After the date, they allegedly went to a party at his fraternity house, where he brought her to a dark bedroom upstairs and "a heavy person jumps on top of her. A hand covers her mouth. Someone gets between her legs. Someone else kneels on her hair. And for the next three hours she's brutally raped and beaten, with Drew and another upperclassman supposedly shouting out instructions to the pledges, referring to Jackie as 'it'." According to Goldberg, "It is an account of a sober, well-planned gang rape by seven fraternity pledges at the direction of two members."[17] After leaving the party around 3 a.m., allegedly with bruises and blood stained clothes, Jackie called her three best friends, "Andy", "Randall" and "Cindy", for support.[18] In Rolling Stone's version, Jackie's friends discouraged her from going to the hospital to protect her reputation and because Andy and Randall planned to rush fraternities and worried their association with Jackie might hurt their chances if she reported it.[17] Erdely wrote that Randall was no longer friends with Jackie and, "citing his loyalty to his own frat, declined to be interviewed".[16]

Jackie's academic performance reportedly declined, and she became socially withdrawn due to emotional distress. In May 2013, Jackie reported the sexual assault to dean and head of UVA's Sexual Misconduct Board, Nicole Eramo, who, according to a recap in New York magazine, offered three options: "file a criminal complaint with the police, file a complaint with the school, or face her attackers with Eramo present to tell them how she feels".[16] The university would not take further action unless Jackie disclosed the names of the individuals or the fraternity involved. In September 2013, Eramo connected Jackie with Emily Renda, a UVA staff member, recent graduate and leader in the college's sexual assault support group One Less.[19] Two years later, in search of a college student to feature in a story about sexual assaults that occur at a prestigious university, Erdely interviewed Renda, who suggested Jackie for the story and made the introduction.[17][20]

Initial response from UVA community

[edit]

Within hours of the article's publication, UVA president Teresa Sullivan had called the governor's chief of staff and the Charlottesville police chief to start preparing a response. She said her initial reaction was surprise and "a certain air of disbelief" because during her 44-minute interview for the story, Erdely never brought up Jackie or asked about any of the allegations made in the article. Sullivan said: "I was plainly not prepared for what the story looked like. Nor do I think her characterization of my interview was fair."[21][22]

The next day, Phi Kappa Psi voluntarily suspended chapter activities at UVA for the duration of the investigation.[23][24] A few days later, President Sullivan suspended all Greek organizations until January 9, 2015.[25]

UVA's student newspaper The Cavalier Daily described mixed reactions from the student body, stating: "For some, the piece is an unfounded attack on our school; for others, it is a recognition of a harsh reality; and for what I suspect is a large majority of us, it falls somewhere in between."

Also within the first day following publication, Phi Kappa Psi's fraternity house at UVA was vandalized with spray-painted graffiti that read "suspend us", "UVA Center for Rape Studies", and "Stop raping people". In addition, several windows were broken with bottles and cinder blocks, and police officials said that the group received "disparaging messages" on social media.[26] A few hours after the incident, several news groups received an anonymous letter claiming responsibility for the vandalism and demanding that the university implement harsher consequences for sexual assault (mandatory expulsion), conduct a review of all fraternities on campus, the resignation of Nicole Eramo, and the implementation of harm reduction policies at fraternity parties.[24] A few days later, hundreds of people participated in a protest and march organized by UVA faculty as "part of a series of responses to the recently published Rolling Stone article".[27] A student quoted in The Daily Progress said that men at a nearby bar were "quick to yell 'insults and slurs' at the protesters as they walked by".[28] A local business owner expressed support of non-violent demonstrations and told The Cavalier Daily that "The only way thing[s] change is if you talk about what's happening."[27] The march ended outside of the Phi Kappa Psi house where protesters challenged a perceived "culture of sexual assault at the University".[28] Community members offered suggestions for immediate steps administration could take to implement preventive measures and address safety concerns regarding sexual assault. One student protester told The Cavalier Daily: "I really hope the University takes this article and the protest movement as a sign that they need to be more transparent about the way they deal with sexual assault."[27] Four participants who were sitting on the steps to the Phi Kappa Psi house were arrested on trespassing charges for refusing to move when police officers asked them to leave.[28]

The Interfraternity Council (IFC) at UVA released a statement on its website in response to the article that said: "an IFC officer was interviewed by Rolling Stone regarding the culture of sexual violence at the University. Although the discussion was lengthy, the reporter elected not to include any of the information from the interview in her article."[29]

Story's veracity

[edit]Questions emerge

[edit]Richard Bradley, editor-in-chief of Worth magazine, was among the first mainstream journalists to question the Rolling Stone article, in a blog entry written on November 24, 2014. Recalling his experience with Stephen Glass before he was exposed for journalism fraud, Bradley argued the article relied heavily on confirmation bias. He also faulted Erdely for not interviewing Jackie's alleged assailants or the three friends who tried to dissuade her from going to the police.[30][31] After an interview Erdely gave to Slate, in which she was questioned about the way she investigated the piece, some commentators escalated their questioning of the veracity of the article. It was later revealed Erdely had not interviewed any of the men accused of the rape.[32][33] Erdely defended her decision not to interview the accused by saying that the contact page on the fraternity's website "was pretty outdated".[34] The Washington Post media critic Erik Wemple rejected Erdely's statement, saying that the severity of the accusations she was reporting required "every possible step to reach out and interview them, including e-mails, phone calls, certified letters, FedEx letters, UPS letters and, if all of that fails, a knock on the door. No effort short of all that qualifies as journalism."[35]

Fraternity officials, who rejected the published allegations, noted a number of discrepancies in the story: there was no party held on the night that Jackie was allegedly raped, no fraternity member matched the description in the story of the "ringleader" of the rape, and details about the layout of the fraternity house provided by the accuser were wrong. Fraternity officials also noted that, prior to the Rolling Stone story, there had never been a criminal investigation or allegation of sexual assault against an undergraduate member of the chapter.[36] Fraternity officials further disputed a claim in Erdely's piece that said the rape had occurred as part of a pledging ritual by observing that pledging on the UVA campus occurs in spring, not autumn as the story stated. They said that no pledges were resident in the fraternity at the time Erdely claimed.[37]

The Washington Post reporters later interviewed the accuser at the center of Erdely's story and two of the friends that Rolling Stone said she had met on the night of the incident. The accuser told the Post that she had felt "manipulated" by Erdely, and claimed she asked Erdely not to quote her in the article, a request the journalist denied.[18] Jackie requested that her assailants not be contacted, and Rolling Stone agreed.[38]

Bruce Shapiro of Columbia University said that an engaged and empathetic reporter will be concerned about inflicting new trauma on the victim: "I do think that when the emotional valence of a story is this high, you really have to verify it." He also explained that experienced reporters often work only with women who feel strong enough to deal with the due diligence required to bring the article to publication.[39]

The two friends confirmed to the Post that they remembered meeting Jackie on the night of the incident, that she was distraught but not visibly injured or bloodied, and that details she provided then were different from those in the Rolling Stone article. One friend, Ryan Duffin (called "Randall" in the Rolling Stone article), told The Washington Post that he had never spoken to any reporter from Rolling Stone, although Erdely had claimed him as a source to corroborate the accuser's story.[18][40][41] Sandra Menendez, a student who claimed to have been interviewed by Erdely but who was not directly quoted in the article, told CNN that she and others became uncomfortable after speaking with Erdely, concluding she had "an agenda".[42]

Existence of "Drew"

[edit]The article uses the pseudonym "Drew" to refer to a third-year student at the University of Virginia who takes Jackie to the fraternity party where the alleged rape takes place. "Drew" gives "instruction and encouragement" to the seven rapists. Jackie's friends in the story have provided evidence since then that the man Rolling Stone calls "Drew" was electronically introduced to them as "Haven Monahan."[43] Jackie forwarded messages from "Monahan", and "Monahan" exchanged messages with Jackie's friends, including sending a picture of "himself" directly to Ryan Duffin.[44] However, media investigations have determined that no student named "Haven Monahan" has attended the University of Virginia;[45] the portrait of "Haven Monahan" is an image of a classmate of Jackie's in high school, who has never attended the University of Virginia;[46] the three telephone numbers through which "Haven Monahan" contacted Jackie's friends are registered "internet telephone numbers" that "enable the user to make calls or send SMS text messages to telephones from a computer or iPad while creating the appearance that they are coming from a real phone"[47] and love letters written by Jackie and forwarded by "Haven Monahan" to Ryan Duffin are largely plagiarized from scripts of the TV series Dawson's Creek and Scrubs.[48]

Per records released by Yahoo under subpoena in 2016, Haven Monahan's e-mail account was created from inside the University of Virginia "only one day before that same account sent an email to Jackie's friend Ryan Duffin" in 2012. The same account was accessed on March 18, 2016, from inside ALTG, Stein, Mitchell, Muse & Cipollone LLP, Jackie's legal firm.[49][50] After initially refusing to answer whether Jackie had access to or created the Haven Monahan email account, on May 31, 2016, Jackie's law firm filed court papers acknowledging they had recently accessed "Haven Monahan's" e-mail account for the purpose "of confirming that documents Eramo requested for the lawsuit were no longer in Jackie's possession."[51]

"Haven Monahan", as reported by T. Rees Shapiro, "ultimately appeared to be a combination of names belonging to people Jackie interacted with while in high school in Northern Virginia. Both of those people—who attend different colleges and bear no resemblance to the description Jackie gave of her attacker—said in interviews that they knew of Jackie but did not know her well and did not have contact with her after she left for the University of Virginia."[52] According to news articles covering lawsuits resulting from the Rolling Stone article, Jackie concocted the Haven Monahan persona in a catfishing scheme directed at Duffin, who had not responded to romantic overtures that Jackie had directed at him.[53][54][55]

Rolling Stone apologizes

[edit]Initially, Erdely stood by her story, stating: "I am convinced that it could not have been done any other way, or any better."[56] But on December 5, 2014, Rolling Stone published an online apology, stating that there appeared to be "discrepancies" in the accounts of Erdely's sources and that their trust in the accuser was misplaced.[57] A subsequent tweet sent by Rolling Stone managing editor Will Dana offered further comment on Erdely's story: "[W]e made a judgement—the kind of judgement reporters and editors make every day. And in this case, our judgement was wrong."[58] On December 6, Rolling Stone updated the apology to say the mistakes in the article were the fault of Rolling Stone and not of its source, while noting that "there now appear to be discrepancies in Jackie's account".[59]

The New York Observer stated that Rolling Stone deputy managing editor Sean Woods (the editor directly responsible for the article)[60] tendered his resignation to the magazine's owner, Jann Wenner. Wenner, who was reportedly "furious" at Erdely's story, declined to accept the resignation.[61] In the aftermath of the collapse of the story, Dana noted: "Right now, we're picking up the pieces."[62]

Rolling Stone's lawyer told jurors in a 2016 trial that Rolling Stone was victim of a "hoax" and a "fraud", and added with regard to Jackie: "the magazine's editorial staff was no match for Jackie ... 'she deceived us, and we do know it was purposeful'."[63]

Erdely apologizes

[edit]Erdely publicly apologized for the article on April 5, 2015,[64] though her apology did not include specific mention of the fraternity or the members of the fraternity who were accused, instead mentioning only "the U.V.A. community".[65] The Columbia Journalism Review called the apology "a grudging act of contrition".[66]

Spokesmen for both Wenner[67] and Dana said that Erdely would continue to write articles for Rolling Stone.[68]

2016 comments by Jackie

[edit]On October 24, 2016, in a video deposition, Jackie said, "I stand by the account I gave Rolling Stone. I believed it to be true at the time."[69][70] Around the same time, WCAV of Charlottesville, Virginia, published the audio of Jackie's 2014 statements to Erdely.[71]

Debate

[edit]Media reaction

[edit]The Washington Post journalist Erik Wemple criticized the story's graphic details of the alleged crime and said that it was hard to believe due to the "diabolical" description. A number of commentators accused the magazine of setting rape victims "back decades", while The Washington Post described the Rolling Stone story as a "catastrophe for journalism".[33][72][73] Natasha Vargas-Cooper, a columnist at The Intercept, said that Erdely's decision not to interview the accused fraternity members showed "a horrendous, hidden bias ... the premise that none of these guys would tell the truth if asked", while a staff editorial in The Wall Street Journal charged that "Ms. Erdely did not construct a story based on facts, but went looking for facts to fit her theory."[74][75] Lauren Kling of the Poynter Institute criticized Rolling Stone for "blaming [the] source" instead of taking ownership of their own errors.[76] Anna Merlan, a writer for Jezebel, who had earlier called Reason columnist Robby Soave an "idiot" for expressing skepticism of the Rolling Stone story, declared: "I was dead fucking wrong, and for that I sincerely apologize."[77] Merlan had also labeled journalist Richard Bradley's doubts about the article a "giant ball of shit".[78]

On December 6, The Washington Post's media critic Erik Wemple called for all Rolling Stone staff who were involved with the story to be fired. Wemple posited that the claims presented by the magazine were so incredible that editors should have called for further inquiry before publication. "Under the scenario cited by Erdely", Wemple wrote, "the Phi Kappa Psi members are not just criminal sexual-assault offenders, they're criminal sexual-assault conspiracists, planners, long-range schemers. If this allegation alone hadn't triggered an all-out scramble at Rolling Stone for more corroboration, nothing would have."[79] An editorial in the Boston Herald declared: "a fifth-grader would've done some basic fact-checking before potentially ruining men's lives" before repeating the call for the firing of Rolling Stone staff involved in the story.[80]

Journalist Caitlin Flanagan, who wrote an exposé in The Atlantic titled "The Dark Power of Fraternities: A yearlong investigation of Greek houses", told On the Media that she was concerned that Erdely's article could inhibit reforms of the Greek system. She said: "I think we've gone backwards 30 years. And I think the level of devastation that this Rolling Stone report that's now looking to go from a misremembered event to perhaps an actual hoax." Flanagan noted that "what Rolling Stone has pushed me into is that I have now become someone who is on the side of fraternities and defending fraternities."[81]

Writing for Time, columnist Cathy Young said that the unraveling of Erdely's article "exposed the troubling zealotry of advocates for whom believing rape claims is somewhat akin to a matter of religious faith".[82] Christina Hoff Sommers, being interviewed by John Stossel for Reason, commented that the story "proved to be a sort of gothic fantasy, a male-demonizing fantasy. It was absurd."[83]

After two Vanderbilt University football players were convicted of rape on January 27, 2015, Richard Bradley, who was the first mainstream journalist to question the Rolling Stone story, wrote a blogpost titled "Why Didn't Sabrina Rubin Erdely Write about Vanderbilt?" In the post, he asked: "Is Vanderbilt just not as sexy a story as UVA?"[84][85] Robby Soave in Reason's Hit & Run Blog responded to Bradley's query about why Erdely chose UVA over Vanderbilt, arguing:[86]

At the end of the day, UVA's incredible story fit Erdely's narrative better than Vanderbilt's credible one. Erdely wanted to tell the story of a campus body and university administration behaving indifferently to an unspeakable crime. ... What distinguished the UVA story from anything else ever reported was that the assault did not involve drugs or alcohol, required elaborate planning, and involved so many people that the perps could not have reasonably expected to get away with it—a confluence of factors that caused the allegations to have substantially more in common with ones that ultimately proved to be false, like the Duke lacrosse case and Tawana Brawley incident.

Local reaction

[edit]Students at the University of Virginia expressed "bewilderment and anger" following Rolling Stone's apology for its story, with one female student declaring "Rolling Stone threw a bomb at us." Virginia Attorney-General Mark Herring said he found it "deeply troubling that Rolling Stone magazine is now publicly walking away from its central storyline in its bombshell report on the University of Virginia without correcting what errors its editors believe were made."[87]

Emily Renda, the university's project coordinator for sexual misconduct, policy and prevention declared that "Rolling Stone played adjudicator, investigator and advocate and did a slipshod job at that."[88] Sociology professor W. Bradford Wilcox, meanwhile, tweeted that "I was wrong to give it [the Rolling Stone story] credence."[89] Writing in Politico two days after the "story fell apart", Julia Horowitz, deputy editor of the university's campus newspaper, described the feeling among students: "The campus—relatively oversaturated with emotion after a semester of significant trauma—feels as if it is on stand-by, poised in anticipation of where the next torrent of news will take us."[90]

Response of fraternity and sorority groups

[edit]Within days following the unraveling of the Rolling Stone story, the North American Interfraternity Conference, the National Panhellenic Council, and the Fraternity and Sorority Political Action Committee demanded that the University of Virginia "immediately reinstate operations for all fraternity and sorority organizations on campus" and issue an apology to Greek students.[91] On December 8, the University of Virginia restated their original decision that the suspensions would be lifted on the resumption of classes in the new term, on January 9.[92]

After Phi Kappa Psi was reinstated at the start of the 2015 Spring semester, UVA Phi Psi President Stephen Scipione said, "We are pleased that the University and the Charlottesville Police Department have cleared our fraternity of any involvement in this case... In today's 24-hour news cycle, we all have a tendency to rush to judgment without having all of the facts in front of us. As a result, our fraternity was vandalized, our members ostracized based on false information."[93]

Accuser scrutinized

[edit]On December 8, 2014, ABC News reported that the person quoted by Erdely as alleging a rape at Phi Kappa Psi had retained an attorney.[94]

On December 10, 2014, The Washington Post published an updated account of its inquiry into the Rolling Stone article.[46] Slate reported that the Post account strongly implied Jackie's tale of rape had been fabricated in an attempt to win over "Randall", who had previously rebuffed her romantic advances. Writing in Slate, Hannah Rosin described the new The Washington Post investigation as close "to calling the UVA gang rape story a fabrication".[95][96] Emily Renda, who was a University of Virginia student at the time of the alleged attack and in whom Jackie also confided, said that she had become suspicious as to the veracity of Jackie's story prior to the Rolling Stone report, commenting to a The Washington Post editor: "I don't even know what I believe."[40] In the aftermath, Jackie was characterized as "a really expert fabulist storyteller" by Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner in an April 5, 2015 interview.[60][97] At the subsequent trial, one of Jackie's friends the night of the alleged attack testified that their friendships eventually dwindled because of Jackie's "tendency to fabricate things".[98]

Key discrepancies according to The Washington Times

[edit]In Erdely's story, Jackie is lured into an alleged seven-man rape by U. Va. upperclassman "Drew". Prior to the alleged event, Jackie provided evidence of her relationship with "Drew" to her friends by supplying a phone number for "Drew", with whom Jackie's friends subsequently exchanged messages. The Washington Times determined that "Drew"'s "telephone" and "Blackberry" numbers were in fact "Internet phone numbers that enable the user to make calls or send SMS text messages to telephones from a computer or iPad while creating the appearance that they are coming from a real phone". "Drew" eventually sent a photo of "himself" to Jackie's friends, but "the man depicted in that photograph never attended U. Va" and was a high-school classmate of Jackie.[47]

Key discrepancies according to ABC News

[edit]In Erdely's story, Jackie sank into depression after the alleged rape and was holed up in her dorm room for a while. Her friends, however, told ABC News that she seemed fine after the alleged assault,[99] contradicting Jackie's former roommate, Rachel Soltis, who claimed that Jackie "was depressed, withdrawn, and couldn't wake up in the mornings" following the alleged rape.[16] In Erdely's story, Jackie tells her three friends the night of the alleged event that she was raped by seven men over a three-hour period while rolling on a mat of broken glass. The three friends disclosed to ABC News their actual names – Alex Stock's pseudonym was "Andy", Kathryn Hendley's was "Cindy", Ryan (Duffin) was "Randall"[99] – and went on record that on the night of the alleged event Jackie told the two men that she was forced to fellate five men while a sixth stood by.[99]

Key discrepancies according to The Washington Post

[edit]In Erdely's story, the rape was supposed to have occurred during a party at Phi Kappa Psi as part of a pledging ritual. Phi Kappa Psi countered by noting that there had been no party held on the night of the alleged attack and no pledges resided in the house at that time of year. In response to those revelations, Jackie's father declared that Phi Kappa Psi had been misidentified and the attack had occurred at a different fraternity, though he did not elaborate as to which one. However, that statement seemed to contradict an earlier assertion the accuser had made to The Washington Post, in which she stated: "I know it was Phi [Kappa] Psi, because a year afterward, my friend pointed out the building to me."[18]

In Erdely's story, Jackie disclosed to friends Cindy, Andy, and Randall the identity of her date to the fraternity party and said that he was the ringleader of the rape. Later media analysis of photos Jackie showed her friends of her date demonstrated that they were pictures taken from the public social media profile of a former high-school classmate of Jackie, who was not a student of the University of Virginia, did not live in the Charlottesville area, and was out of state at an athletic competition the day of the alleged attack.[46] Jackie's friends Cindy, Andy, and Randall had become suspicious as to whether Jackie's date to the fraternity party where she was allegedly raped was a real person. Prior to the date, they attempted to locate him in a student directory and were unable to find evidence that he existed. The trio also sent text messages to a phone number Jackie said was the mobile phone of her date and were surprised that the owner of the phone number responded primarily with flattering messages about Randall, whom Jackie was romantically interested in.[100][101][a]

In 2012 Jackie told her friends that she had been accosted by five men, though she later testified to Erdely that she had been attacked by seven, with two more directing and encouraging the rape.[40] Erdely said that Jackie regained consciousness alone in the fraternity after 3 a.m. and fled the building blood-spattered and bruised, phoning three friends for help. They arrived "minutes later" and found her on the corner next to the building. However, The Washington Post stated that the three friends reported getting called at 1 a.m.[46] and meeting Jackie a mile away from the fraternities, and that they saw "no blood or visible injuries". The Post did report, however, that Jackie appeared distraught after the rape allegedly took place.[18]

Key discrepancies according to The Philadelphia Inquirer

[edit]Inquirer media columnist Michael Smerconish recounted that when he interviewed Erdely about the story on Sirius XM radio, she told him: "I talked to all of her friends, all the people that she confided in along the way." But as Smerconish wrote, "[S]he did not talk to all of Jackie's friends. In fact, her failure to speak to the three friends in whom Jackie supposedly confided immediately after the alleged incident was perhaps the most egregious of a string of journalistic failures."[104]

Investigations

[edit]Police investigation

[edit]On January 12, 2015, the University of Virginia reinstated the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity after the police investigation concluded that no incident had occurred at the fraternity. According to Charlottesville Police Capt. Gary Pleasants, Phi Kappa Psi has been cleared; "We found no basis to believe that an incident occurred at that fraternity, so there's no reason to keep them suspended."[93][105][106] On March 23, 2015, police noted that Jackie refused to cooperate with law enforcement during the investigation. Charlottesville Police Chief Timothy Longo explained, "We would've loved to have had Jackie come in ... and tell us what happened so we can obtain justice ... even if the facts were different."[107]

Over the course of 4 months, the Charlottesville Police spoke to 70 people, including Jackie's friends, Phi Kappa Psi fraternity brothers, and employees at the UVA Aquatic Center, where Jackie worked. No one supplied evidence to corroborate Jackie's accusations of a gang rape happening or that the accused rapist, supposedly named "Drew" or "Haven Monahan", even existed. The police were also unable to corroborate Jackie's allegations that two other sexual assaults had taken place at the fraternity house or that she had been assaulted and struck to the face with a bottle in a separate incident. Therefore, the criminal investigation was suspended on March 23.[108][109]

Columbia University School of Journalism's investigation

[edit]After the details in "A Rape on Campus" began to unravel, Rolling Stone's publisher Jann Wenner commissioned Columbia University's School of Journalism to investigate the failures behind the publication of the article.[110] On April 5, 2015, Columbia's 12,000-word review of "A Rape on Campus" was published on both Rolling Stone's and the journalism school's websites. It was prepared by Steve Coll, the dean of Columbia's journalism school; Sheila Coronel, the dean of academic affairs; and Derek Kravitz, a graduate school researcher.[111] The Columbia report stated that "At Rolling Stone, every story is assigned to a fact-checker."[112] Assistant editor Elisabeth Garber-Paul provided fact-checking.[113][114]

The fact-checker concluded that Ryan – "Randall" under pseudonym – had not been interviewed, but that the article had pretended he had been. The Columbia report cited the fact-checker: "I pushed. ... They came to the conclusion that they were comfortable" with not making it clear to readers that they had never contacted Ryan.[112][115] Ultimately, the report determined that Rolling Stone had exhibited confirmation bias and failed to perform basic fact checking by relying excessively on the accuser's account without verifying it through other means.[60][116]

The Columbia report also found a failure in journalistic standards by either not making contact with the people they were publishing derogatory information about, or when they did, by not providing enough context for people to be able to offer a meaningful response.[116] The report also states that the article misled readers with quotes where attribution was unclear and used pseudonyms inappropriately as a way to address these shortcomings.[116]

The report concluded, "Rolling Stone's repudiation of the main narrative in "A Rape on Campus" is a story of journalistic failure that was avoidable. The failure encompassed reporting, editing, editorial supervision and fact-checking. The magazine set aside or rationalized as unnecessary essential practices of reporting that, if pursued, would likely have led the magazine's editors to reconsider publishing Jackie's narrative so prominently, if at all. The published story glossed over the gaps in the magazine's reporting by using pseudonyms and by failing to state where important information had come from."[117] It points out that Rolling Stone staff were initially unwilling to recognize these deficiencies and denied a need for policy changes.[116]

Reactions to investigations

[edit]Rolling Stone's reaction

[edit]Rolling Stone fully retracted "A Rape on Campus" and removed the article from its website.[60][116] However, Coco McPherson, who is in charge of Rolling Stone's fact-checking operation, said, "I one-hundred percent do not think that the policies that we have in place failed."[115] Rolling Stone managing editor Will Dana was also cited on the Columbia report: "It's not like I think we need to overhaul our process, and I don't think we need to necessarily institute a lot of new ways of doing things."[115] Jill Geisler in the Columbia Journalism Review reacted to Dana's statement by saying, "At a time when humility should guide a leader's comments, that quote carries the aroma of arrogance."[118]

Jann Wenner added that "Will Dana, the magazine's managing editor, and the editor of the article, Sean Woods, would keep their jobs." Sabrina Erdely would also continue to write for Rolling Stone.[60] Wenner laid blame for the magazine's failures on Jackie. In an interview with The New York Times, he called her, "a really expert fabulist storyteller", and added, "obviously there is something here that is untruthful, and something sits at her doorstep."[119]

In response to these statements, Megan McArdle wrote in Bloomberg View, "Rolling Stone can't even apologize right."[120]

Rolling Stone announced that Will Dana would leave his job at the magazine, effective August 7, 2015. When asked if Dana's departure was influenced by the debacle surrounding Erdely's article, the magazine's publisher responded that "many factors go into a decision like this".[121] Erik Wemple of The Washington Post called Dana's departure "four months too late".[122] Dana was replaced by Jason Fine, the managing editor of Men's Journal.[123]

Phi Kappa Psi's reaction

[edit]After the Charlottesville Police concluded that there was no evidence of a crime having occurred at Phi Kappa Psi during their press conference on March 23, 2015, Stephen Scipione, the president of Phi Kappa Psi's UVA chapter, announced that his fraternity is "exploring its legal options to address the extensive damage caused by Rolling Stone".[124] He added, "False accusations have been extremely damaging to our entire organization, but we can only begin to imagine the setback this must have dealt to survivors of sexual assault."[125][126]

Phi Kappa Psi's national headquarters released the following statement: "That Rolling Stone sought to turn fiction into fact is shameful...The discredited article has done significant damage to the ability of the chapter's members to succeed in their educational pursuits and besmirched the character of undergraduate students at the University of Virginia who did not deserve the spotlight of the media." They went on to call for Rolling Stone to "fully and unconditionally retract its story and immediately remove the story from its website".[127] Phi Kappa Psi's national president Scott Noble stated that they were "now pursuing serious legal action toward Rolling Stone, the author and editor, and even Jackie".[citation needed]

University of Virginia's reaction

[edit]After both the Charlottesville Police press conference and Columbia University's investigative report, UVA President Teresa Sullivan released the following statement:

Rolling Stone's story, 'A Rape on Campus', did nothing to combat sexual violence, and it damaged serious efforts to address the issue. Irresponsible journalism unjustly damaged the reputations of many innocent individuals and the University of Virginia. Rolling Stone falsely accused some University of Virginia students of heinous, criminal acts, and falsely depicted others as indifferent to the suffering of their classmate. The story portrayed University staff members as manipulative and callous toward victims of sexual assault. Such false depictions reinforce the reluctance sexual assault victims already feel about reporting their experience, lest they be doubted or ignored. The Charlottesville Police Department investigation confirms that far from being callous, our staff members are diligent and devoted in supporting and caring for students. I offer our community's genuine gratitude for their devotion and perseverance in their service.[128]

Consequences

[edit]The Washington Post reported that the members of Phi Kappa Psi "went into hiding for weeks after their home was vandalized with spray paint calling them rapists and bricks that broke their windows", and had to escape to hotels. The report indicated the college students suffered disgust, emotion, and confusion. Some students "actually had to leave the room while they were reading [the article] because they were so upset." A former student who graduated in 2013 said "the day [the article] came out was the most emotionally grueling of my life."[129] Phi Kappa Psi members received death threats and the president of the university postponed all events related to its fraternities and sororities until mid-January 2015.[130]

One month after the publication of the Rolling Stone article, the Rector of the University of Virginia, George Keith Martin, accused the magazine of "drive-by journalism" when he stated, "Like a neighborhood thrown into chaos by drive-by violence, our tightly knit community has experienced the full fury of drive-by journalism in the 21st century."[131]

According to the Columbia report, "Allen W. Groves, the University dean of students, and Nicole Eramo, an assistant dean of students, separately wrote to the authors of this report that the story's account of their actions was inaccurate." Columbia published Groves' letter, where he contrasts video[132] of his statements to the University of Virginia Board of Visitors in September 2014 with the text of Erdely's published article, which differ significantly,[citation needed] and concludes that Erdely's article contains "bias and malice".[133] Erdely furthermore reported that Office for Civil Rights Assistant Secretary Catherine E. Lhamon called Grove's statements at the meeting "deliberate and irresponsible".[134]

On January 30, 2015, Teresa Sullivan, the President of the University of Virginia, acknowledged that the Rolling Stone story was "discredited" in her State of the University Address. In her remarks, she said, "Before the Rolling Stone story was discredited, it seemed to resonate with some people simply because it confirmed their darkest suspicions about universities—that administrations are corrupt; that today's students are reckless and irresponsible; that fraternities are hot-beds of deviant behavior."[135][136][137]

The Rolling Stone article had a negative effect on applications to the University of Virginia. For the first time since 2002, applications to the university dropped. Prior to the publication of the story, early-action applications were up 7.5 percent with 16,187 applicants. However overall applications were down 0.7 percent to 31,107 in the aftermath of the publication.[138]

National sorority leaders ordered UVA sororities to not interact with fraternities during Boys Bid Night when fraternities admit new pledges. Virginia sorority members called the restrictions "unnecessary and patronizing".[139]

Sexual assault skepticism

[edit]Due to increased social skepticism about the prevalence of sexual assault created by the unraveling of Erdely's Rolling Stone report, the Military Justice Improvement Act would be "much harder" to enact, according to Margaret Carlson,[140] and ultimately did not pass in that congressional session. Lindy West said that female rape victims will probably be less likely to report sexual assaults for fear of being questioned by "some teenage 4Channer".[141] Froma Harrop issued a call for media outlets to begin to publicly name rape accusers, explaining that "reporters and editors should expand their sensitivities to include the reputations of those accused, not always justly".[142]

Several commentators hypothesized that allegations of rape against Bill Cosby, which surfaced at the same time as the publication of "A Rape on Campus", would be less damaging to the comedian as a result of the seeming collapse of the Rolling Stone story. When Camille Cosby spoke about the rape allegations against her husband Bill, she said: "We all followed the story of the article in the Rolling Stone concerning allegations of rape at the University of Virginia. The story was heart-breaking, but ultimately appears to be proved untrue. Many in the media were quick to link that story to stories about my husband – until that story unwound."[143] Writing for Bloomberg, Zara Kessler observed that, "suddenly, every Cosby accuser is a potential 'Jackie'—although we don't yet know precisely what it means to be a 'Jackie.' How honest are the intentions of Cosby's accusers?"[144]

The North American Interfraternity Conference and the National Panhellenic Council, meanwhile, announced that they had retained the services of Squire Patton Boggs to lobby the U.S. Congress to take action to ensure that Greek-letter organizations are protected from future accusations of the kind leveled in Erdely's article.[145]

Media sources and commentators discussed the allegations in the context of the reported "rape culture" or a rampant sexual assault epidemic that activists had claimed existed on U.S. college campuses. The media commentators noted that the claims of a rape culture's existence on campuses was not supported by U.S. government statistics or other measures.[146][147][148] Harvey A. Silverglate in The Boston Globe referenced the Rolling Stone article in opining that the college sexual assault "scare" follows a long tradition of runaway, exaggerated social epidemics that "have ruined innocent lives and corrupted justice. A return to sanity is called for before more wreckage occurs."[149]

Media criticism

[edit]The Washington Post media critic Erik Wemple stated that everyone connected to this story at Rolling Stone should be fired.[79] After the Charlottesville Police made their official report, Wemple said: "What is left of the Rolling Stone piece? Very little. There's some reporting on the university's culture, which shouldn't be taken seriously in light of the fraud exposed by the police; there's some reporting on the university leadership's approach to the issue, which shouldn't be taken seriously in light of the fraud exposed by the police."[150]

National Review columnist Jonah Goldberg has called for Phi Kappa Psi to sue Rolling Stone, while at least one legal expert has opined that there is a high likelihood of "civil lawsuits by the fraternity members or by the fraternity itself against the magazine and maybe even some university officials".[151][152] ABC News has reported that the accuser, Jackie, herself might be sued.[94] By December 5, 2014, Christopher Pivik, a former member of Phi Kappa Psi at the University of Virginia, had retained attorney Andrew Miltenberg.[153] According to Miltenberg, he specializes in "defamation and complex internet and First Amendment issues".[154]

Columbia journalism professor Bill Grueskin called the story "a mess—thinly sourced, full of erroneous assumptions, and plagued by gaping holes in the reporting".[155] The Columbia Journalism Review declared the story the winner of "this year's media-fail sweepstakes".[156] The Poynter Institute named the story the "Error of the Year" in journalism.[157]

Lawsuits

[edit]On May 12, 2015, UVA associate dean Nicole Eramo, chief administrator for handling sexual assault issues at the school, filed a $7.5 million defamation lawsuit in Charlottesville Circuit Court against Rolling Stone and Erdely, claiming damage to her reputation and emotional distress. Said the filing: "Rolling Stone and Erdely's highly defamatory and false statements about Dean Eramo were not the result of an innocent mistake. They were the result of a wanton journalist who was more concerned with writing an article that fulfilled her preconceived narrative about the victimization of women on American college campuses, and a malicious publisher who was more concerned about selling magazines to boost the economic bottom line for its faltering magazine, than they were about discovering the truth or actual facts."[158] In February 2016, the judge in the lawsuit ordered Jackie to appear at a deposition on April 5, 2016.[159] On March 30, 2016, The Washington Post reported that Jackie's lawyers requested the April deposition be cancelled, to avoid having her "revisit her sexual assault".[160] However, on April 2, 2016, the judge denied the motions and ordered Jackie to appear for a deposition on April 6, to be held at a secret location.[161] On November 4, 2016, after 20 hours of deliberation,[162] a jury consisting of eight women and two men found Rolling Stone, the magazine's publisher and Erdely liable for defaming Eramo.[163] On November 7, 2016, the jury decided that Rolling Stone and Erdely were liable for $3 million in damages to Eramo.[164] The lawsuit was settled on April 11, 2017.[165]

On November 9, 2015, Phi Kappa Psi filed a $25 million lawsuit against Rolling Stone in state court "to seek redress for the wanton destruction caused to Phi Kappa Psi by Rolling Stone's intentional, reckless, and unethical behavior".[166][167] In September 2016, the magazine sought to have the lawsuit dismissed; however, a circuit court judge ruled that the suit could proceed.[168] On June 13, 2017, the lawsuit was settled for $1.65 million.[169]

A further lawsuit by a number of members of the fraternity was greenlighted by a court of appeals on September 19, 2017, after originally being dismissed by a lower court in June 2016.[170] The lawsuit was settled on December 21, 2017.[171]

In popular culture

[edit]Street artist Sabo papered Hollywood with posters styled like a Rolling Stone cover featuring the headline "Rape Fantasies and Why We Perpetuate Them". The poster featured an image of Lena Dunham, whose own allegations of rape had recently come under scrutiny, and included a sidebar reference to "A Rape on Campus" that read "Our UVA Rape Apology: Ooops, we did it AGAIN!!!"[172]

Law & Order: SVU featured an episode titled "Devastating Story" in its 16th season whose plot was based on the UVA case. It features a fictional character named Heather Manning who was based on Jackie. In the episode, Heather fabricates a gang rape at a fraternity.[173]

In May 2022, an off-Broadway play adapted from the UVA case and resulting legal battles titled Retraction premiered in New York City at Theatre Four at Theatre Row.[174][175]

See also

[edit]- Campus sexual assault

- Duke lacrosse case, a widely reported 2006 case of a false accusation of rape at Duke University

- False accusation of rape

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Rolling Stone and UVA: The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Report". Rolling Stone. April 5, 2015. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

"With [the publication of this article], we are officially retracting 'A Rape on Campus.'

- ^ Daniel Sanchez (April 28, 2017). "Rolling Stone Faces Millions More In Defamation Charges". Digital Music News. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

First published in Rolling Stone in 2014, 'A Rape on Campus: A Brutal Assault and Struggle for Justice' turned out to be seriously fake news.

- ^ Victor Davis Hanson (January 26, 2017). "Fake News: Postmodernism By Another Name". Hoover Institution. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

A somewhat similar fake news story about rape was promulgated by Rolling Stone in a 9,000-word article ("A Rape on Campus") that supposedly detailed a savage gang rape in 2012 of a University of Virginia first year co-ed.

- ^ "Dan Liljenquist: News stories about fake news stories". December 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ GRACE GUARNIERI (November 5, 2016). "Rolling Stone, Sabrina Rubin Erdely deemed liable in dean's defamation suit for University of Virginia rape story". Salon. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

The Rolling Stone story, which was eventually retracted in April 2015, centered on student Jackie Coakley and her falsified story of being gang raped

- ^ Shapiro, T. Tees (May 18, 2016). "Lawyers in Rolling Stone lawsuit file new evidence that 'Jackie' created fake persona". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ McNiff, Eamon; Effron, Lauren; Schneider, Jeff (2017). "How the Retracted Rolling Stone Article 'A Rape on Campus' Came to Print". ABC 20/20. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "'Jackie' testifies: Rolling Stone story was 'what I believed to be true at the time'". The Guardian. October 24, 2016. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

Jackie responded: "I stand by the account I gave to Rolling Stone. I believed it to be true at the time."

- ^ "'I believed it to be true:' Jackie stands by her story as Rolling Stone trial continues". WTVR.com. October 25, 2016. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- ^ "Rolling Stone's investigation: 'A failure that was avoidable'". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ "UVA dean awarded $3M in Rolling Stone magazine case". www.cbsnews.com. November 7, 2016. Archived from the original on September 8, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (December 21, 2017). "Rolling Stone Settles Last Remaining Lawsuit Over UVA Rape Story". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, K. C.; Taylor, Stuart Jr. (May 22, 2018). The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at America's Universities. Encounter Books. ISBN 9781594039881. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shatz, Naomi (September 7, 2017). "The Misguided Idea Of The War Over Campus Sexual Assault". HuffPost. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Erdely, Sabrina (November 19, 2014). "A Rape on Campus: A Brutal Assault and Struggle for Justice at UVA". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hartmann, M. (July 30, 2015), "Everything We Know About the UVA Rape Case [Updated]", New York Magazine, archived from the original on April 2, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ a b c Goldberg, Jonah (December 1, 2014), "Rolling Stone rape story sends shock waves – and stretches credulity", Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, CA, archived from the original on January 25, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ a b c d e Shapiro, T. Rees (December 5, 2014), "Key elements of Rolling Stone's U-Va gang rape allegations in doubt", The Washington Post, archived from the original on April 4, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ Coronel; et al. (April 5, 2015), "Rolling Stone and UVA: The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Report", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on April 13, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ Farhi, P. (November 28, 2014), "Sabrina Rubin Erdely, woman behind Rolling Stone's explosive U-Va alleged rape story", The Washington Post, archived from the original on March 11, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ Quizon, D. (January 31, 2015), "UVA's Sullivan reflects on tenure, Rolling Stone controversy, student privacy laws", The Daily Progress, archived from the original on June 10, 2017, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ Farhi, Paul (December 19, 2014), "Rolling Stone never asked U-Va. about specific gang rape allegations, according to newly released e-mails and audio recording", The Washington Post, archived from the original on December 21, 2014, retrieved February 1, 2015

- ^ "LETTER: Statement from Phi Kappa Psi", The Cavalier Daily, November 20, 2014, archived from the original on March 27, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ a b Elliott, A. (November 20, 2014), "Students claiming responsibility for Phi Kappa Psi vandalism submit anonymous letter", The Cavalier Daily, archived from the original on March 29, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ DeBonis, Mike; Shapiro, T. Rees (November 22, 2014), "U-Va president suspends fraternities until Jan. 9 in wake of rape allegations", The Washington Post, archived from the original on April 24, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ "UVA Fraternity House Vandalized", WVIR-TV, November 20, 2014, archived from the original on March 22, 2016, retrieved April 1, 2016

- ^ a b c Dickerson, Jenna (November 22, 2014), "Protest outside Phi Kappa Psi house leads to four arrests", Cavalier Daily, Charlottesville, VA, archived from the original on March 3, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ a b c Seal, Dean (November 23, 2014), "Hundreds protest at UVA; student says memorial to victims vandalized", The Daily Progress, archived from the original on August 12, 2016, retrieved April 2, 2016

- ^ "The Governing Board of the Inter-Fraternity Council at UVA" (PDF). UVa Interfraternity Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Bradley, Richard (November 24, 2014). "Is the Rolling Stone Story True?". Shots in the Dark. richardbradley.net. Archived from the original on April 9, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Doolittle, Robyn (2019). Had It Coming: What's Fair in the Age of #MeToo. Toronto, Ontario: Penguin Random House. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7352-3659-2. OCLC 1097247909.

- ^ Moynihan, Michael (December 4, 2014). "Why It Was Right to Question Rolling Stones UVA Rape Story". Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Roslin, Hannah. "The Missing Men". 7=Slate. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Farhi, Paul (December 1, 2014). "Author of Rolling Stone article on alleged U-Va. rape didn't contact accused assailants for her report". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (December 2, 2014). "Rolling Stone whiffs in reporting on alleged rape". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Shapiro, Rees (November 20, 2014). "McAuliffe urges investigation at U-Va. after Rolling Stone depiction of sexual assault". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Official Statement from the Virginia Alpha Chapter of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at the University of Virginia". phikappapsi.com. Phi Kappa Psi. Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (December 2, 2014). "Magazine's Account of Gang Rape on Virginia Campus Comes Under Scrutiny". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (December 7, 2014). "Rolling Stone Tries to Regroup After Campus Rape Article is Disputed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wemple, Erik (December 8, 2014). "Updated apology digs bigger hole for Rolling Stone". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (December 6, 2014). "U-Va. remains resolved to address sexual violence as Rolling Stone account unravels". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (December 7, 2014). "Rolling Stone apologizes for rape article: What now?". CNN. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "There's More Bizarre Evidence That UVA Student Jackie's Alleged Rapist Doesn't Exist". Business Insider. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Sara Ganim; Ray Sanchez (December 17, 2014). "Friends' accounts differ from victim in UVA rape story – CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Hadas Gold. "More problems with the Rolling Stone piece". POLITICO. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Shapiro, T. Rees (December 10, 2014). "U-Va. students challenge Rolling Stone account of alleged sexual assault". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ a b "U.Va. rape accuser's friends begin to doubt story – Washington Times". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Ganim, Sara; Sanchez, Ray (December 17, 2014). "Friends' accounts differ significantly from victim in UVA rape story". CNN. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Seal, Dean (May 19, 2016). "'Jackie' withholding documents in Rolling Stone case, lawyers for UVa associate dean say". The (Charlottesville) Daily Progress. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

Yahoo showed that the email account was created in Charlottesville at an IP address "allocated to the University of Virginia" on Oct. 2, 2012, only one day before that same account sent an email to Jackie's friend Ryan Duffin. Yahoo further showed that the Monahan email had last been accessed from an IP address in Washington, D.C., that was "allocated to ALTG, Stein, Mitchell, Muse & Cipollone LLP"—the same firm representing Jackie—on March 18, days before and after Jackie's counsel stated they were not in possession of the Haven Monahan documents.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (May 18, 2016). "Lawyers in Rolling Stone lawsuit file new evidence that 'Jackie' created fake persona". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^

Shapiro, T. Rees (June 1, 2016). "Lawyers in Rolling Stone lawsuit acknowledge 'Jackie' has ties to fake persona". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

After initially refusing to address the charge that Jackie made up the Haven Monahan email account, the lawyers for Jackie admitted in a later filing that they had recently accessed the Monahan e-mail, but solely for the purpose of confirming that documents Eramo requested for the lawsuit were no longer in Jackie's possession.

- ^ T. Rees Shapiro (March 23, 2015). "Police find no evidence of alleged sexual assault at U-Va. fraternity – The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (January 8, 2016). "'Catfishing' over love interest might have spurred U-Va. gang-rape debacle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ "'Catfishing' may have begun gang rape scandal at University of Virginia". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 17, 2016. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "These Surreal "Catfishing" Texts May Have Prompted The UVA Rape Scandal". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (December 2, 2014). "Magazine's Account of Gang Rape on Virginia Campus Comes Under Scrutiny". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "A Note to Our Readers". Rolling Stone. December 5, 2014. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Mai-Duc, Christine (December 6, 2014). "Rolling Stone editor: 'Failure is on us' in UVA gang rape story". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Holley, Peter (December 7, 2014). "After apology, Rolling Stone changes its story once more". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Somaiya, Ravi (April 5, 2015). "Rolling Stone Article on Rape at University of Virginia Failed All Basics, Report Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Kurson, Ken (December 9, 2014). "Rolling Stone Deputy Editor Tendered Resignation; Wenner Declines". The New York Observer. New York, NY. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (December 7, 2014). "Rolling Stone Tries to Regroup After Campus Rape Article Is Disputed". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^

Shapiro, T. Rees (November 4, 2016). "Jury finds reporter, Rolling Stone responsible for defaming U-Va. dean with gang rape story". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

Scott Sexton, an attorney for Rolling Stone, told the jurors in his closing statement that the magazine 'acknowledges huge errors in not being more dogged ... It's the worst thing to ever happen to Rolling Stone.' [...] Sexton said that, in effect, Erdely and Rolling Stone had fallen victim to what he called at points a 'hoax,' a 'fraud' and a 'perfect storm.' The magazine's editorial staff was no match for Jackie, Sexton said, noting that the magazine was not sure what exactly had happened to her, but admitted 'she deceived us, and we do know it was purposeful.'

- ^ "Statement from Writer of Rolling Stone Article Sabrina Erdely". The New York Times. April 5, 2015. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Rachel Brody. "Rolling Stone Retracts UVA Fraternity Rape Story, Pundits React – US News". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Rolling Stone fails to take full responsibility for its actions". Columbia Journalism Review. Cjr.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (April 6, 2015). "Major 'failures' found in Rolling Stone's 'A Rape on Campus'". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Valerie Bauerlein; Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg (April 6, 2015). "Probe of Now-Discredited Rolling Stone Article Didn't Find Fireable Error". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^

Laura French (October 24, 2016). "'I believed it to be true:' Jackie stands by her story as Rolling Stone trial continues". CBS 6 News – WTVR. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

Jackie testified, 'I stand by the account I gave Rolling Stone. I believed it to be true at the time.'

- ^ Richer, Alanna Durkin (October 24, 2016). "'Jackie' Says She Felt Pressure to Be in Rolling Stone Story". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

The woman whose harrowing account of being gang-raped at a University of Virginia fraternity house was the centerpiece of a now-discredited Rolling Stone magazine article testified in a deposition heard by the public for the first time on Monday that the story was what she believed 'to be true at the time.'

- ^ Courteney Stuart (October 22, 2016). "Rolling Stone magazine "Jackie" recording released". CBS 19 Newsplex. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ "Rolling Stone just wrecked an incredible year of progress for rape victims". The Verge. December 5, 2014. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Schow, Ashe (December 3, 2014). "If false, Rolling Stone story could set rape victims back decades". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on December 3, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Like a Rolling Stone". The Wall Street Journal. December 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Vargas-Cooper, Natasha (December 5, 2014). "Hey, Feminist Internet Collective: Good Reporting Does Not Have To Be Sensitive". The Intercept. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Merlan, Anna (December 5, 2014). "Rolling Stone backs off story of alleged fraternity rape at UVA". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Merlan, Anna (December 5, 2014). "Rolling Stone Partially Retracts UVA Story Over 'Discrepancies'". Jezebel. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Merlan, Anna (December 2014). "'Is the UVA Rape Story a Gigantic Hoax?' Asks Idiot". Jezebel. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Wemple, Erik (December 5, 2014). "'Rolling Stone' 's disastrous U-Va. story: A case of real media bias". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "Apparently, this Rolling Stone gathers no facts". Boston Herald. December 7, 2014. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "SPECIAL: The UVA Story". On the Media. December 6, 2014. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Cathy Young (December 31, 2014). "A Better Feminism for 2015". Time. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Stossel, John (March 4, 2015). "Raping Culture". Reason. Archived from the original on March 5, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Bradley, Richard (January 27, 2015). "Why Didn't Sabrina Rubin Erdely Write about Vanderbilt?". Shots In The Dark. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ "Jury: Ex-Vandy players guilty of rape". ESPN. January 28, 2015. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ Soave, Robby (January 28, 2015). "Why Did Rolling Stone Writer Choose UVA, Not Vanderbilt, for Gang Rape Exposé?". Reason. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ Lauerman, John; McDonald, Michael (December 6, 2014). "UVA Anger Focused on Rolling Stone After Rape Story Discredited". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Advocates Fear Impact of Rolling Stone Apology". Fox News. Associated Press. December 6, 2014. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (December 5, 2014). "Rolling Stone Rolls Off Cliff". American Conservative. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Horowitz, Julia (December 6, 2014). "Why We Believed Jackie's Rape Story". Politico. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "University urged to end Greek groups' suspension". Philadelphia Inquirer. December 8, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "UVA Issues Statement Regarding Fraternal Suspension". WVIR-TV. December 8, 2014. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ a b Shapiro, T. Rees (January 12, 2015). "Police clear U-Va. fraternity, say rape did not happen there". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Davis, Lindsay (December 8, 2014). "UVA Student in Rolling Stone Rape Story Reportedly Hires Attorney". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ Rosin, Hannah (December 10, 2014). "The Washington Post Inches Closer to Calling the UVA Gang Rape Story a Fabrication". Slate. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (December 10, 2014). "Did Jackie Make The Whole Thing Up?". American Conservative. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Report: Rolling Stone rape article 'journalistic failure'". Hosted2.ap.org. Archived from the original on April 9, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ O'Neal, Tab; Hausman, Sandy (October 28, 2016). "Updated: Jurors Hear From 'Jackie's' Friends in Rolling Stone Trial". www.wvtf.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c "New Questions Raised About Rolling Stone's UVA Rape Story". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Byers, Dylan (December 10, 2014). "U-Va. students challenge Rolling Stone account of alleged sexual assault". Politico. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ "'Catfishing' over love interest might have spurred U-Va. gang-rape debacle". The Washington Post. January 8, 2016. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "What Happened to Jackie? Watch Full Episode |". ABC. October 14, 2016. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "The Lies of UVA's Jackie: Read All the Catfishing Texts She Sent Her Crush". Reason.com. February 10, 2016. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "The Pulse: Red flags on piece were there". Philly.com. April 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Phi Kappa Psi Reinstated at the University of Virginia". UVA Today. January 12, 2015. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ "Police Investigation Clears UVA Phi Psi Fraternity". Businessinsider.com. January 12, 2015. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Couric, Katie, "UVA rape investigation: Police say no evidence to support allegations reported by Rolling Stone Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine", Yahoo! News, March 23, 2014

- ^ Robinson, Owen; Stolberg, Sheryl (March 23, 2015). "Police Find No Evidence of Rape at UVA Fraternity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Larry O'Dell (March 23, 2015). "Police: No Evidence of Gang-Rape at University of Virginia". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (December 22, 2014). "Rolling Stone farms out review of U-Va. rape story to Columbia Journalism School". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Libby Nelson (April 5, 2015). "Rolling Stone retracts story on alleged UVA rape". Vox. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Rolling Stone's investigation: 'A failure that was avoidable' - Columbia Journalism Review". Cjr.org. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Fact-Checker Didn't Ask About Alleged Rape Victim in Emails With UVA Officials". The Huffington Post. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (December 19, 2014). "U-Va.-Rolling Stone e-mails highlight university's attempt to correct magazine". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wemple, Erik (March 18, 2015). "Columbia Journalism School report blasts Rolling Stone". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Coronel, Sheila. "Rolling Stone and UVA: The Columbia School of Journalism Report". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Chris Cillizza (April 6, 2015). "Rolling Stone isn't firing anyone. That's terrible for journalism". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Jill Geisler (April 6, 2015). "Should there have been firings at Rolling Stone?". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Ashe Schow (April 5, 2015). "Rolling Stone publisher: U.Va. accuser an 'expert fabulist storyteller'". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Megan McArdle (April 6, 2015). "Rolling Stone Can't Even Apologize Right". Bloomberg View. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (July 29, 2015). "Will Dana, Rolling Stone's Managing Editor, to Depart". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (July 30, 2015). "Editor who oversaw Rolling Stone's rape story departs magazine, four months too late". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (August 2, 2015). "Rolling Stone Appoints a New Managing Editor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "UVA's Phi Psi Responds to Cleared Rape Allegations". aig.alumni.virginia.edu. May 26, 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Berenson, Tessa (March 24, 2015). "UVA Fraternity Considers Legal Action Over Rolling Stone Article". Time. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Faulders, Katherine; Shapiro, Emily (March 23, 2015). "UVA Fraternity Exploring Legal Options to Address 'Extensive Damage Caused by Rolling Stone'". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ John Bacon & Marison Bello (March 23, 2015). "Police unable to verify 'Rolling Stone' rape story". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "President Teresa A. Sullivan Statement Regarding Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Report". UVA Today. April 5, 2015. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (January 14, 2015). "U-Va. Phi Psi members speak about impact of discredited gang rape allegations". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Zurcher, Anthony (December 5, 2014). "Rolling Stone apologises for Virginia rape story". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (December 19, 2014). "U-Va. board leader denounces 'drive-by journalism' of Rolling Stone's rape article". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ BOV Student Affairs & Athletics Committee with Full Board – September 12, 2014. University of Virginia. September 16, 2014. Archived from the original on November 30, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Dean Coll and Dean Coronel Ltr from AW Groves March 6, 2015-2.pdf". Google Docs. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Jacobs, Peter (December 8, 2014). "Here Are Some Big Things The Rolling Stone Story About Rape At UVA Got Right". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "Prepared Remarks for Presidential Address on the University" (Press release). University of Virginia. January 30, 2015. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Schow, Ashe (January 30, 2015). "U.Va. president admits rape story was false; keeps restrictions on fraternities". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.