High culture

"High culture" is a term now used in a number of different ways in academic discourse, whose most common meaning is the set of cultural products, mainly in the arts, held in the highest esteem by a culture.

In more popular terms, it is the culture of an upper class such as an aristocracy or an intelligentsia, but it can also be defined as a repository of a broad cultural knowledge, a way of transcending the class system. It is contrasted with the low culture or popular culture of, variously, the less well-educated, barbarians, Philistines, or the masses.[1] Both high culture and folk culture act as the repository of shared and accumulated traditions functioning as a living continuum between the past and present.

Concept

Although it has a longer history in Continental Europe, the term was introduced into English largely with the publication in 1869 of Culture and Anarchy by Matthew Arnold, although he most often uses just "culture". Arnold defined culture as "the disinterested endeavour after man's perfection" (Preface) and most famously wrote that having culture meant to "know the best that has been said and thought in the world"—a specifically literary definition, also embracing Philosophy, which is now rather less likely to be considered an essential component of High Culture, at least in the English-speaking cultures. Arnold saw high culture as a force for moral and political good, and in various forms this view remains widespread, though far from uncontested. The term is contrasted with popular culture or mass culture and also with folk culture, but by no means implies hostility to these.

T. S. Eliot's Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1948) was an influential work which saw high culture and popular culture as necessary parts of a complete culture. The Uses of Literacy by Richard Hoggart (1957) was an influential work along somewhat the same lines, concerned with the cultural experience of those, like himself, who had come from a working-class background before university. In America, Harold Bloom has taken a more exclusive line in a number of works, as did F. R. Leavis earlier—both, like Arnold, being mainly concerned with literature, and unafraid to champion vociferously the literature of the Western canon.

In the Western tradition high culture has historical origins in the intellectual and aesthetic ideals of ancient Greece and Rome. Within this classical ideal certain authors and their modes of language were held up as models of an elevated style and good form as for instance the Attic dialect of ancient Greek associated with the great philosophers and dramatists of Periclean Athens, or Ciceronian Latin. Later, especially during the Renaissance, these values were deeply imbibed by the cultural upper classes, and (as evinced in works like The Courtier by Baldasare Castiglione) knowledge of the classics became part of the aristocratic ideal. Over time, the refined classicism of the Renaissance was expanded to embrace a broader canon of authors in the modern languages that included figures such as Shakespeare, Goethe, Cervantes and Victor Hugo.

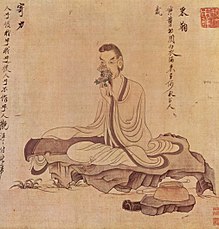

In both the Western and some East Asian traditions, art that demonstrates the imagination of the artist has been accorded the highest status. In the West this tradition goes back to the Ancient Greeks, and was reinforced in the Renaissance and by Romanticism, although the latter also did away with the hierarchy of genres within the fine arts established in the Renaissance. In China there was a distinction between the literati painting by the scholar-officials and the work produced by common artists, working in largely different styles, or the decorative arts such as Chinese porcelain which were produced by unknown craftsmen working in large factories. In both China and the West the distinction was especially clear in landscape painting, where for centuries imaginary views, produced from the imagination of the artist, were considered superior works.

For centuries an immersion in high culture was deemed an essential part of the proper education of the gentleman, and this ideal was transmitted through high-status schools and institutions throughout Europe and the United States. As it has evolved, Western notions of high culture have been associated at various times with: The study of "humane letters" especially the Greek and Latin classics and more broadly all works considered to be part of "the canon"; the cultivation of refined etiquette and manners; an appreciation of the fine arts – especially sculpture and painting; a knowledge of such literature, drama, and poetry considered to be of high caliber; enjoyment of European classical music and opera; religion and theology often with a special focus on Europe's predominantly Christian tradition; rhetoric and politics; the study of philosophy and history; a taste for gourmet cuisine and wine; being well traveled and especially "The Grand Tour of Europe"; certain sports associated with the upper classes, such as polo, equestrianism, fencing, and yachting.

High art

Much of high culture consists of the appreciation of what is sometimes called "High Art". This term is rather broader than Arnold's definition and besides literature includes music, visual arts (especially painting), and traditional forms of the performing arts (including some cinema). The decorative arts would not generally be considered High Art.[2]

The cultural products most often regarded as forming part of high culture are most likely to have been produced during periods of High civilization, for which a large, sophisticated and wealthy urban-based society provides a coherent and conscious aesthetic framework, and a large-scale milieu of training, and, for the visual arts, sourcing materials and financing work. Such an environment enables artists, as near as possible, to realize their creative potential with as few as possible practical and technical constraints. Although the Western concept of high culture naturally concentrates on the Graeco-Roman tradition, and its resumption from the Renaissance onwards, such conditions existed in other places at other times.

Art music

Art music (or serious music[3] or erudite music) is an umbrella term used to refer to musical traditions implying advanced structural and theoretical considerations and a written musical tradition.[4] The notion of art music is a frequent and well-defined musicological distinction - musicologist Philip Tagg, for example, refers to art music as one of an "axiomatic triangle consisting of 'folk', 'art' and 'popular' musics". He explains that each of these three is distinguishable from the others according to certain criteria, with high cultural music often performed to an audience whilst folk music would traditionally be more participatory.[5] In this regard, "art music" frequently occurs as a contrasting term to "popular music" and to "traditional" or "folk music".[4][6][7]

Art film

Art film is the result of filmmaking which is typically a serious, independent film aimed at a niche market rather than a mass market audience.[8] Film critics and film studies scholars typically define an "art film" using a "...canon of films and those formal qualities that mark them as different from mainstream Hollywood films",[9] which includes, among other elements: a social realism style; an emphasis on the authorial expressivity of the director; and a focus on the thoughts and dreams of characters, rather than presenting a clear, goal-driven story. According to the film scholar David Bordwell, "art cinema itself is a film genre, with its own distinct conventions."[10]

Promotion of high culture

The term has always been susceptible to attack for elitism, and, in response, many proponents of the concept devoted great efforts to promoting high culture among a wider public than the highly educated bourgeoisie whose natural territory it was supposed to be. There was a drive, beginning in the 19th century, to open museums and concert halls to give the general public access to high culture. Figures such as John Ruskin and Lord Reith of the BBC in Britain, Leon Trotsky and others in Communist Russia, and many others in America and throughout the western world have worked to widen the appeal of elements of high culture such as classical music, Art by old masters and the literary classics.

With the widening of access to university education, the effort spread there, and all aspects of high culture became the objects of academic study, which with the exception of the classics had not often been the case until the late 19th century. University liberal arts courses still play an important role in the promotion of the concept of high culture, though often now avoiding the term itself.

Especially in Europe, governments have been prepared to subsidize high culture through the funding of museums, opera and ballet companies, orchestras, cinema, public broadcasting stations such as BBC Radio 3, ARTE and in other ways. Organisations such as the Arts Council of Great Britain, and in most European countries, whole ministries administer these programmes. This includes the subsidy of new works by composers, writers and artists. There are also many private philanthropic sources of funding, which are especially important in the US, where the federally funded Corporation for Public Broadcasting also funds broadcasting. These may be seen as part of the broader concept of official culture, although often a mass audience is not the intended market.

Theoreticians

High culture and its relation to mass culture have been, in different ways, a central concern of much theoretical work in cultural studies, critical theory, media studies and sociology, as well as in postmodernism and in many strands of Marxist thought. It was especially central to the concerns of Walter Benjamin, whose 1935/36 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction has been highly influential, as has the work of Theodor Adorno. Gramscianism can see ruling class culture as "an instrument of social control".[11]

High culture also became an important concept in political theory on nationalism for writers such as Ernest Renan and Ernest Gellner, who saw it as a necessary component of a healthy national identity. Gellner's concept of a high culture extended beyond the arts; he defined it in Nations and Nationalism (1983) as: "...a literate codified culture which permits context-free communication". This is a distinction between different cultures, rather than within a culture, contrasting high with simpler, agrarian low cultures.

Pierre Bourdieu's book: La Distinction (English translation: Distinction - A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste) (1979) is a study influential in sociology of another much broader, class-based, definition of high culture, or "taste", which includes etiquette, appreciation of fine food and wine, and even military service, but also references different social codes supposedly observed in the dominant class, and that are not accessible to the lower classes. This partly reflects a French conception of the term which is different from the more serious-minded Anglo-German concept of Arnold, Benjamin, Leavis or Bloom, and also French cultural habits in his day. Bourdieu introduced the concept of cultural capital, knowledge and habits acquired by a dominant class upbringing that his surveys in post-war France found led to increased relative social and economic success despite a supposedly egalitarian educational system.

See also

Notes

- ^ Gaye Tuchman, Nina E. Fortin (1989). "ch. 4 The High-Culture Novel". Edging women out: Victorian novelists, publishers and social change. ISBN 978-0-415-03767-9Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Dormer, Peter (ed.), The Culture of Craft, 1997, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0719046181, 9780719046186, google books

- ^ a b "Music" in Encyclopedia Americana, reprint 1993, p. 647

- ^ a b Denis Arnold, "Art Music, Art Song", in The New Oxford Companion to Music, Volume 1: A-J, (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1983): 111. ISBN 0-19-311316-3

- ^ Philip Tagg, "Analysing Popular Music: Theory, Method and Practice", Popular Music 2 (1982): 41.

- ^ "Music" in Encyclopedia Americana, reprint 1993, p. 647

- ^ Philip Tagg, "Analysing Popular Music: Theory, Method and Practice", Popular Music 2 (1982): 37-67, here 41-42.

- ^ Art film definition – Dictionary – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

- ^ Barbara Wilinsky. Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema at Google Books. University of Minnesota, 2001 (Commerce and Mass Culture Series). See also review in 32&pg=PA171&dq=%22canon+of+films+and+those+formal+qualities+that+mark+them+as+different+from+mainstream+Hollywood+films%22 High culture, p. 171, at Google Books, Journal of Popular Film & Television, 2004. Retrieved 2012-01-09.

- ^ Keith, Barry. Film Genres: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press: 2007. (page 1)

- ^

McGregor, Craig (1997). Class in Australia (1 ed.). Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia Ltd. p. 301. ISBN 0-14-008227-1.

[...] elite culture is often an instrument of social control [...]

References

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin and London: University of Texas Press.

- Gans, Herbert J. Popular Culture and High Culture: an Analysis and Evaluation of Taste. New York: Basic Books, 1974. xii, 179 p. ISBN 0-465-06021-8

- Ross, Andrew. No Respect: Intellectuals & Popular Culture. New York: Routledge, 1989. ix, 269 p. ISBN 0-415-90037-9 (pbk.)