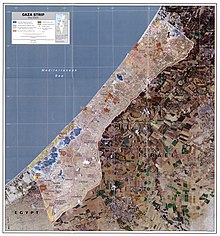

Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip has been under military occupation by Israel since 6 June 1967, when Israeli forces captured the territory, then occupied by Egypt, during the Six-Day War. Although Israel unilaterally withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, the United Nations, international human rights organizations and several legal scholars regard the Gaza Strip to still be under military occupation by Israel, as Israel still maintains direct control over Gaza's air and maritime space, six of Gaza's seven land crossings, a no-go buffer zone within the territory, and the Palestinian population registry.[1] Israel, the United States, and other legal, military, and foreign policy experts otherwise contend that Israel "ceded the effective control needed under the legal definition of occupation" upon its disengagement in 2005.[2] Israel, supported by Egypt, continues to maintain a blockade of the Gaza Strip, limiting the movement of goods and people in and out of the Gaza Strip. The blockade has been categorized as a form of occupation and illegal collective punishment.[3]

History

1956–1957 Israeli occupation

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (April 2024) |

1967–1993 Israeli military administration

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (April 2024) |

2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza

While the disengagement of Israel from Gaza was first proposed in 2003 by Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, and adopted by the government and Knesset in 2004 and 2005, the actual unilateral dismantlement of the settlements occurred in 2005.[4][5] The decision to disengage from Gaza was not met with support from the Israeli public with a May 2004 referendum showing 65% of voters were against the disengagement plan.[6]

2023–present Israel–Hamas war

In early January 2024, during the Israel–Hamas war, Israel reoccupied most of the northern Gaza Strip after Israel claimed that it had dismantled 12 Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades battalions on 7 January.[7][8][9] This led to the beginning of the Insurgency in the North Gaza Strip and also the beginning of the Israeli reoccupation of the Gaza Strip, some 19 years after Israel had disengaged from the Gaza Strip in 2005 due to stiff resistance from the Palestinians. However, Israel has been continuously imposing a blockade of the Gaza Strip since 2007.

At the beginning of the Israel–Hamas war, Israel made it clear that controlling the Gaza Strip was one of the main goals.[10] In late January 2024, Benjamin Netanyahu said that he "will not compromise on full Israeli control" over Gaza.[11]

In March 2024, Israel started carving through farmland and demolishing Palestinian homes and schools in the Gaza Strip to create a new buffer zone. Palestinians would be barred from the new buffer zone in Gaza.[12]

Israeli settlements

By 2005, there were 9,000 Israeli settlers spread across 21 Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip, while around 1.3 million Palestinians lived there. The first settlement was built in 1970, soon after Israel occupied the Gaza Strip following the Six-Day War. Each Israeli settler disposed of 400 times the land available to the Palestinian refugees, and 20 times the volume of water allowed to the peasant farmers of the Strip.[13] Following disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005, all Israeli settlers were evacuated and all settlements were dismantled.[14]

In late January 2024, it was reported by an unnamed Israeli military officer that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and others in the government had requested that military members begin to establish permanent bases in the Gaza Strip amid the 2023 Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip.[15]

See also

- Policy paper: Options for a policy regarding Gaza's civilian population

- Israeli-occupied territories

- Israeli occupation of the West Bank

- Israel and apartheid

- List of Israeli settlements

References

- ^ Sanger, Andrew (2011). "The Contemporary Law of Blockade and the Gaza Freedom Flotilla". In M.N. Schmitt; Louise Arimatsu; Tim McCormack (eds.). Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law - 2010. Vol. 13. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 429. doi:10.1007/978-90-6704-811-8_14. ISBN 978-90-6704-811-8.

Israel claims it no longer occupies the Gaza Strip, maintaining that it is neither a State nor a territory occupied or controlled by Israel, but rather it has 'sui generis' status. Pursuant to the Disengagement Plan, Israel dismantled all military institutions and settlements in Gaza and there is no longer a permanent Israeli military or civilian presence in the territory. However, the Plan also provided that Israel will guard and monitor the external land perimeter of the Gaza Strip, will continue to maintain exclusive authority in Gaza air space, and will continue to exercise security activity in the sea off the coast of the Gaza Strip as well as maintaining an Israeli military presence on the Egyptian-Gaza border, and reserving the right to reenter Gaza at will. Israel continues to control six of Gaza's seven land crossings, its maritime borders and airspace and the movement of goods and persons in and out of the territory. Egypt controls one of Gaza's land crossings. Gaza is also dependent on Israel for water, electricity, telecommunications and other utilities, currency, issuing IDs, and permits to enter and leave the territory. Israel also has sole control of the Palestinian Population Registry through which the Israeli Army regulates who is classified as a Palestinian and who is a Gazan or West Banker. Since 2000 aside from a limited number of exceptions Israel has refused to add people to the Palestinian Population Registry. It is this direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza that has led the United Nations, the UN General Assembly, the UN Fact Finding Mission to Gaza, International human rights organisations, US Government websites, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and a significant number of legal commentators, to reject the argument that Gaza is no longer occupied.

- Scobbie, Iain (2012). Elizabeth Wilmshurst (ed.). International Law and the Classification of Conflicts. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-965775-9.

Even after the accession to power of Hamas, Israel's claim that it no longer occupies Gaza has not been accepted by UN bodies, most States, nor the majority of academic commentators because of its exclusive control of its border with Gaza and crossing points including the effective control it exerted over the Rafah crossing until at least May 2011, its control of Gaza's maritime zones and airspace which constitute what Aronson terms the 'security envelope' around Gaza, as well as its ability to intervene forcibly at will in Gaza.

- Gawerc, Michelle (2012). Prefiguring Peace: Israeli-Palestinian Peacebuilding Partnerships. Lexington Books. p. 44. ISBN 9780739166109.

While Israel withdrew from the immediate territory, it remained in control of all access to and from Gaza through the border crossings, as well as through the coastline and the airspace. In addition, Gaza was dependent upon Israel for water, electricity sewage communication networks and for its trade (Gisha 2007. Dowty 2008). In other words, while Israel maintained that its occupation of Gaza ended with its unilateral disengagement Palestinians – as well as many human rights organizations and international bodies – argued that Gaza was by all intents and purposes still occupied.

- Scobbie, Iain (2012). Elizabeth Wilmshurst (ed.). International Law and the Classification of Conflicts. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-965775-9.

- ^ Dagres, Holly (2023-10-31). "Israel claims it is no longer occupying the Gaza Strip. What does international law say?". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Palmer Report Did Not Find Gaza Blockade Legal, Despite Media Headlines". Amnesty International USA. 6 September 2011.

- ^ Sara M. Roy (2016). The Gaza Strip. Institute for Palestine Studies USA, Incorporated. pp. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-88728-321-5.

- ^ "Knesset Approves Disengagement Implementation Law (February 2005)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ "40 Years Of Israeli Occupation". www.arij.org. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

- ^ Jhaveri, Ashka; Soltani, Amin; Moore, Johanna; Tyson, Kathryn; Braverman, Alexandra; Carl, Nicholas (7 January 2024). "Iran Update, January 7, 2024". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Colin P. (5 February 2024). "The Counterinsurgency Trap in Gaza". Foreign Affairs. 103 (2). Council on Foreign Relations. ISSN 2327-7793. OCLC 863038729. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Rasgon, Adam; Boxerman, Aaron (23 February 2024). "As Gaza War Grinds On, Israel Prepares for a Prolonged Conflict". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "Netanyahu says IDF will control Gaza after war, rejects notion of international force". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Netanyahu Says No Compromise on Full Israeli Control in Gaza". Voice of America. January 20, 2024.

- ^ AbdulKarim, Camille Bressange, Dion Nissenbaum, Juanje Gómez and Fatima. "How Israel's Proposed Buffer Zone Reshapes the Gaza Strip". WSJ.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Filiu, Jean-Pierre (2014-08-14). Gaza: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020190-6.

- ^ "Israel's disengagement from Gaza (2005) | Withdrawal, Map, & Hamas | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-04-11.

- ^ Kemal, Levent (24 January 2024). "Israel planning 'permanent army stations' in Gaza". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

External links

- "From 'Occupied Territories' to 'Disputed Territories'" by Dore Gold Archived 2011-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Israeli Water Interests in the Occupied Territories", from Security for Peace: Israel's Minimal Security Requirements in Negotiations with the Palestinians Archived 2005-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, by Ze'ev Schiff, 1989. Retrieved October 8, 2005.

- Howell, Mark (2007). What Did We Do to Deserve This? Palestinian Life under Occupation in the West Bank, Garnet Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85964-195-8

- Occupied Palestinian Territory, The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)