Japanese Grand Prix

| Suzuka Circuit (2003–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 45 |

| First held | 1963 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 5.807 km (3.608 miles) |

| Race length | 307.471 km (191.053 miles) |

| Laps | 53 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

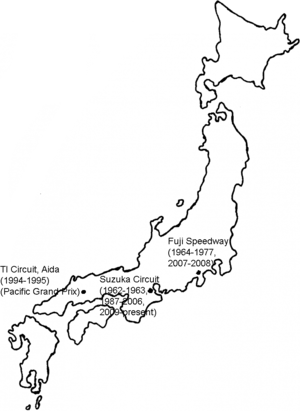

The Japanese Grand Prix (Template:Lang-ja) is a motor racing event in the calendar of the Formula One World Championship. Historically, Japan has been one of the last races of the season, and as such the Japanese Grand Prix has been the venue for many title-deciding races, with 13 World Champions being crowned over the 34 World Championship Japanese Grands Prix that have been hosted. Japan was the only Asian nation to host a Formula One race (including the Pacific Grand Prix) until Malaysia joined the calendar in 1999.

The first two Formula One Japanese Grands Prix in 1976 and 1977 were held at the Fuji Speedway, before Japan was taken off the calendar. It returned in 1987 at Suzuka, which hosted the Grand Prix exclusively for 20 years and gained a reputation as one of the most challenging F1 circuits. In 1994 and 1995, Japan also hosted the Pacific Grand Prix at the TI Circuit, making Japan one of only eight countries to host more than one Grand Prix in the same season (the others being Austria, Great Britain, France, Spain, Germany, Italy and the USA). In 2007 the Grand Prix moved back to the newly redesigned Fuji Speedway.[1] After a second race at Fuji in 2008, the race returned to Suzuka in 2009, as part of an alternating agreement between the owners of Fuji Speedway and Suzuka Circuit, perennial rivals Toyota and Honda. However, in July 2009, Toyota announced it would not host the race at Fuji Speedway in 2010 and beyond due to a downturn in the global economy,[2] and so the Japanese Grand Prix was held at Suzuka instead. Suzuka has hosted the Japanese Grand Prix every year since 2009, apart from in 2020 when the Japanese GP was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.[3]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Origins

The first Japanese Grand Prix was run as a sports car race[4] at the Suzuka Circuit 80 kilometres (50 mi) south west of Nagoya in May 1963. In 1964, the race was held at Suzuka again. This marked the beginning of motor racing in earnest in Japan. For the next eight installments, however, the non-championship Grand Prix was run at the Fuji Speedway, 40 miles (64 km) west of Yokohama and 66 miles (106 km) west of the Japanese capital of Tokyo. The circuit had a banked corner called Daiichi and was the scene of many fatal accidents. It was then run as a number of disciplines of motorsports, particularly Formula 2, sports cars and Can-Am-type sprint racing.

Formula One

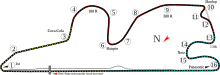

Fuji Speedway

The first Formula 1 Japanese Grand Prix, in 1976, was held at the very fast 2.7-mile Fuji Speedway, minus the banking. The race was to become famous for the title decider between James Hunt and Niki Lauda as it was held during monsoon conditions. Lauda, who had survived a near-fatal crash at the German Grand Prix earlier in the season, withdrew from the race stating that his life was more important than the championship, as did Brazilians Emerson Fittipaldi and Carlos Pace. The torrential rain eventually stopped, and after a slow pit stop that put him down to 5th, Hunt drove hard and climbed up to 3rd, taking the 4 points he needed to win the title by the slender margin of one point over Lauda. American Mario Andretti won the race for his 2nd career win and first for Lotus, ahead of Frenchman Patrick Depailler in the Tyrrell P34. Hunt returned the next year to win the second Japanese Grand Prix, but a collision between Gilles Villeneuve and Ronnie Peterson during the race saw Villeneuve's Ferrari somersault into a restricted area, killing two spectators.[5] Although originally scheduled for an April slot in the 1978 season (which was cancelled), the race did not reappear on the Formula One calendar for another decade, and the race did not return to Fuji for an even greater time.

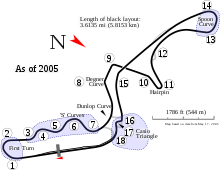

Suzuka Circuit

On Formula 1's return to Japan in 1987, the Grand Prix found a new venue at the redesigned and revamped Suzuka Circuit. The circuit, set inside a funfair, was designed by Dutchman John Hugenholtz and owned by Honda, who used it as a test track. Most notable initially for its layout—Suzuka is the only figure-eight race track to appear on the F1 calendar—the demanding and fast Japanese circuit became very popular among drivers and fans, and it was to see some of the most dramatic and memorable moments in Formula One history.

The first event in 1987 was already a classic. It immediately saw another World Title decided, as Nigel Mansell crashed his Williams-Honda heavily in practice at the Snake Esses and consequently could not start the race due to aggravating an old back injury he had received in his Formula Ford days, effectively handing the title to his teammate Nelson Piquet; the 3rd and final title of his career. Austrian Gerhard Berger won the race for Ferrari, their first victory since 1985.

Alain Prost versus Ayrton Senna

Suzuka played a part in the feud between Frenchman Alain Prost and Brazilian Ayrton Senna. This long battle reached immense levels of controversy and media coverage; this struggle was between two men who were both considered to be by far the best drivers in Formula One at that time.

The 1988 race was a World Championship decider between Senna and Prost – who were McLaren teammates that year. Senna came in with a greater chance of winning the championship, as the points system in those days counted the best 11 results; Senna had retired from one more Grand Prix than Prost had and had been slightly less consistent than the Frenchman, yet this was actually to the Brazilian's advantage; the way the points system worked in those days meant that there was more room for him to score points. McLaren also had obtained superior and fuel-efficient Honda engines from Williams, had a car far better than any of the others, and had won every race of the season except the Italian Grand Prix – McLaren's only double retirement of the season. At the start, Senna made a very bad start, stalling on the grid but then managing to bump-start his car on the down-sloping pit straight. As a result, he dropped to 14th, while Prost took the lead. It then began to rain, and wet-weather specialist Senna stormed around the track, setting a number of fastest laps and passing car after car until he caught Berger in 2nd and then started to catch Prost rapidly. The Frenchman's gearbox was malfunctioning, and the Brazilian caught and passed Prost while the Frenchman was delayed by consistent backmarker Andrea de Cesaris. Senna won the race and his first Drivers' Championship with Prost finishing 2nd, despite the latter scoring more points overall.

The 1989 race was a highly anticipated race, and even with new regulations banning turbo-charged engines, the McLaren-Honda combination was still dominant, they had won 10 of 14 races so far in the season. This race turned out to be one of the most memorable in the sport's history. Prost and Senna, once again McLaren teammates for 1989, were both embroiled in an acrimonious personal feud that had started at the second race of the season and their relationship was, come the race weekend, at such a low point it was virtually non-existent. Very unusual for teammates of a racing team, there was almost zero communication going on between Prost and Senna, and was to the degree where the McLaren team were effectively running as 2 separate teams – with 4 to 5 times more people around Senna than Prost. This was because Senna had a closer relationship with the Honda engineers than Prost; Senna's popularity with the Japanese public thanks to his flat-out driving style benefited Honda in many different ways; and McLaren wanted a long-term partnership with Honda, as their engines were better than all the others. Both Senna and Prost went into the race weekend each knowing what the stakes were. Prost was 16 points ahead of Senna, and the Brazilian was facing nearly insurmountable odds: he had to win at Suzuka to stand any chance of staying in contention of winning the championship going into the next race, which he was obliged to win as well. Senna qualified on pole position 1.5 seconds ahead of Prost who was already working on his race setup in qualifying. Senna's set up meant he was faster around corners, while Prost opted for a set up that made him faster on the straights.

Come race day, the two McLarens were on the front row of the grid, and both McLaren drivers' emotions were running very high. As the starting lights flashed to green, Prost made an excellent start and jumped into the fast first corner ahead of Senna. The two McLaren drivers immediately started to pull away from the rest of the field, with Prost and Senna setting the pace at the highest possible level they could muster. On lap 47, going through the ultra-fast 130R corner, the Brazilian attempted an ambitious pass going into the Casio chicane. Senna was in an awkward position to pass, being on the inside of his teammate, and tried to shove his way past Prost, but the Frenchman decided to be true to words he had said to Senna and McLaren boss Ron Dennis: he would not leave the door open as he had before and give up the position simply for McLaren to be embarrassed by a double retirement. And Prost did exactly that: as he turned into the right handed turn that made up the first part of the chicane, he turned into Senna, and the Frenchman's car hit the Brazilian's car and the two cars were interlocked and both slid off the track and up the chicane's escape road, the Honda V10 engines in both cars stalling.

Prost and Senna were both beached and Prost got out of his car promptly, knowing he had won the championship with Senna's apparent retirement whilst Senna waved towards a group of Suzuka's track marshals, who ran up to the two interlocked cars. So they could separate the two cars, the marshals pushed Senna's car backwards onto the track, which put it in a dangerous position. The marshals then pushed his car forwards while Senna bump-started the engine, and he drove off. Even after being stalled for more than 30 seconds, the furious pace he and Prost had been running at put them both so far ahead of the rest of the field that Senna was still leading the race comfortably in front of Benetton driver Alessandro Nannini. Senna's front nose cone was damaged and going through the Degner bend, it came off; and he pitted to have it changed. Nannini had passed Senna while the Brazilian was in the pits, and after he stormed out of the pits, Senna drove as furiously as he had before, and within 2 laps while making up 2.5 seconds a lap on Nannini he caught and passed the Italian cleanly at the Casio chicane. Senna took the chequered flag, but the podium ceremony proceeded to be delayed. A meeting between Senna, Prost, the McLaren management and FIA officials including the very unpopular FIA and FISA president Jean-Marie Balestre took place immediately post-race. It was thought that Senna was going to be disqualified for receiving external non-team assistance, which was against the rules, but that rule had a loophole: the rule read that if a driver was deemed to be in a dangerous position, they could be push started. But much to almost the entire Formula One paddock's astonishment, it was deemed that Senna was to be disqualified for bypassing the chicane and the marked track after making his way down an escape road bordering the circuit. Cutting the chicane was in effect bypassing the track to gain an advantage – and this was illegal. But this rule was not enforced and generally ignored in those days if a driver was negatively affected in terms of where they stood in the race – which Senna was not. Nevertheless, the Brazilian Senna was infuriated by the decision – and he later said that he struggled to cope for a long time with what happened. Nannini was handed the race victory as a result of Senna's disqualification, and McLaren appealed Senna's disqualification – which was not only denied by Balestre and the FIA but he was handed a $100,000 fine and a six-month suspension, both of which were eventually rescinded. Prost had won the Drivers' Championship for the third time – but this was not official until Senna's retirement from the Australian Grand Prix 2 weeks later, before which McLaren's appeal had been denied.

The 1990 event proved to be just as controversial as the 1989 event. Senna and Prost were once again first and second in the championship – the two men had won 37 of the past 46 Formula One championship races. But the roles had been reversed: the championship situation for Prost was the same as Senna's in the previous year. The Frenchman needed to win both of the final two races to defend the title. The race also was without defending champion Nannini, as his career ended just days after a helicopter crash. As shown in a video of the pre-race drivers' briefing,[6] the drivers were discussing what was to be done if a car was in a dangerous position at the Casio Chicane. Senna was appalled at what he saw as a ridiculous interpretation of badly thought-out rules – and he walked out of the meeting as it was taking place. Senna qualified on pole position, three-tenths ahead of Prost, now driving for Ferrari, who had the next most competitive package that year behind McLaren. Senna requested to change the grid positions in order to move pole position to the cleaner left side of the road, where the racing line was. This was granted, but Balestre intervened and reverted the grid positions back to their original locations, meaning pole position would be on the dirty right side of the track, where all the bits of tire rubber had been thrown from the tires by the Formula One cars. This meant Senna was off the racing line and it would be more difficult for him to make a better start. Frustrated and angry, Senna mimicked Prost's statement of the previous year saying he would not move over if Prost attempted to overtake in the first corner. Senna started from pole, with Prost second (albeit on the racing line). Prost got ahead of Senna – but the more powerful Honda engine in Senna's McLaren meant that he was able to make up a bit of ground. Prost moved over to take the racing line, but Senna dived into the corner to Prost's right to pass him – and as a result he hit the side of Prost's Ferrari. Both cars went straight on and both drivers sped through the gravel trap at 160 mph (260 km/h) and crashed into the tyre wall at the end of the run-off area. Senna and Prost were both unhurt, and neither driver bothered to check to see if the other was okay. This accident meant that Senna won his second world Drivers' Championship. The crash looked somewhat dubious, and nothing was done to Senna by the FIA; because they had done nothing to Prost in 1989 for crashing to Senna, they could not do anything to Senna either, with the collision being declared a "racing incident" in the end. Furious and disgusted, Prost later described Senna as "a man without value". Both drivers have been accused of crashing into the other deliberately and thus the two situations as well as their comments after both incidents have tainted both drivers' reputations in the eyes of most but die-hard fans. Benetton driver Nelson Piquet won his first race in 3 years after Gerhard Berger went off and Nigel Mansell's Ferrari failed in the pits after a pit stop, and Piquet's new teammate Roberto Moreno finished 2nd.

1991–2006

1991 was yet again the showdown for the Drivers' Championship, and it saw Senna and this time Mansell in a competitive but rather unreliable Williams battle for the Drivers' Championship. Prost did not win a race in his uncompetitive Ferrari that year and it turned out to be his last race for the Scuderia that year; he was fired from the team after the race for describing the 643 as having handling like "a truck". This was the last straw for Ferrari; as Prost had been making unsavory comments about the Italian team for some time. The race started, and Mansell went off at the first corner on lap 10, and Senna won his 3rd Drivers' Championship in 4 seasons. Senna let his teammate Gerhard Berger through to win as a "thank you" gesture for his support all season. But during the post-race press conference, Senna then admitted that his actions in 1990 were indeed intentional, and he then called Balestre and the rest of the governing body "stupid people". He admitted that he did what he did the year before because of his refusal to put up with Balestre's continuously illegal manipulation of the Drivers' Championship.

1992 was the first year in which the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka did not in any way determine the championship – Mansell had already won it 4 races before in Hungary with his all-dominant Williams. He retired from the race, as did Senna, and Mansell's teammate Riccardo Patrese took his only victory that year. 1993 was an interesting event; Senna took the lead from Alain Prost (who had won his 4th drivers' title at the previous race) and kept it; additionally, the changeable weather conditions played to Senna's advantage, who was known to be exceptional in wet-weather conditions. He was harassed, however, by Briton newcomer Eddie Irvine, who attempted to pass Senna and unlap himself while battling with Prost's British teammate Damon Hill. Senna won his 40th race in his career from Prost, but he wasn't all smiles. He sought out Irvine, had a heated discussion with the Northern Irishman and punched him in the side of the head; then Senna went on live television for post-race interviews, and used profanity on the live recording in frustration at Irvine, other drivers' alleged bad behavior on the track and at the media, who he claimed were "irresponsible" for sensationalizing some of Senna's dangerous on-track behavior.

By 1994, Prost had retired and Senna was killed at the San Marino Grand Prix, and the Japanese GP that year saw Hill and German Michael Schumacher battle for the Drivers' Championship. Hill crucially won the race ahead of Schumacher; Suzuka was hammered by a torrential downpour which made conditions very difficult for Hill as Schumacher was an acknowledged specialist in wet-weather conditions. 1995 saw an incredible drive from French-Italian Jean Alesi on dry slick tyres in damp conditions. It had rained at the start; but the track was drying. Alesi went into the pits on lap seven, around the time everyone else came in. The French driver began to lap Suzuka in his Ferrari 5 seconds faster than anyone else, and when he came out of the pits, he was 17th – but then over the course of 18 laps climbed to 2nd place, passing car after car while a number of the other cars changed to slick tyres as well. But then Alesi had to serve a drive-through penalty for jumping the start. This did not stop the emotionally highly-strung Alesi: he dropped down to 10th, but pushed hard; and began passing car after car. He then went into the pits and dropped to 13th from 8th as a result. Then he had gone off in the last corner on lap 20 but recovered, and as a result dropped further down the order to 15th. He then went from 15th to 9th in one lap and got into 2nd again behind Schumacher, whom he caught up to and battled with for the lead. This remarkable performance was only to last 5 laps, however: Alesi's Ferrari's driveshaft failed as a result of his excursion earlier and he retired from the race. Schumacher won the race, having already won the Drivers' Championship at the Pacific Grand Prix at Aida.

1996 was the last race of the year, and it saw Williams teammates Jacques Villeneuve and Damon Hill's title struggle come to a showdown at Suzuka. Villeneuve lost a wheel on lap 37 and went off at the first sequence of corners, handing the drivers' title to Damon Hill; however, Hill was never as competitive as he was ever again in Formula One: team owners Frank Williams and Patrick Head decided earlier in the season not to renew Hill's contract.

1997 saw Michael Schumacher win and his title rival Jacques Villeneuve disqualified for ignoring yellow flags during one of the practice sessions.

1998 saw another dramatic title decider between Schumacher and Finn Mika Häkkinen. The two drivers had dueled all season long and Hakkinen led Schumacher by four points heading in the final race at Suzuka. Schumacher started on pole for the race but stalled on the grid, giving Hakkinen in second a clear track in front of him for the start. Now starting from the back of the grid, Schumacher fought hard to catch up, setting numerous fastest laps in his effort to catch his rival. However, on lap 28 a collision between backmarkers resulted in debris being scattered on the circuit. Schumacher ran over the debris, puncturing his right rear tire. The tire caused Schumacher's retirement three laps later, leaving Häkkinen to take victory and his first drivers' championship.

Hakkinen then won his second consecutive drivers' title in 1999, after a fight with Eddie Irvine, Schumacher's Ferrari teammate.

The next 5 events were all won by Ferrari; Schumacher won in 2000–2002 and 2004, and his teammate Rubens Barrichello won in 2003. Schumacher won his 3rd title at the 2000 event: he took advantage of his superior speed in damp conditions during a mid-race rain shower to secure the race win and his first World Championship title for Ferrari. This was Ferrari's first drivers' championship in 21 years. Ferrari completed their domination of the 2002 season by reaching a total points tally of 221 points on the then-used 10-point scoring system. At the 2003 event, Schumacher endured one of the most trying races[original research?] in his career, needing to come at least eighth, he started at fourteenth on the grid – but managed to secure the point he needed to take his sixth World Drivers' Championship, beating the record held by Juan Manuel Fangio. Schumacher had an incident-filled race, having a collision with Takuma Sato and another near collision with his brother. The qualifying session for the 2004 event, which was due to be held on 9 October, was postponed until race day after a typhoon hit Suzuka. This led to the idea of holding qualifying sessions on a Sunday morning (an idea that was abandoned half-way through the following year).

The 2005 race was one of the most exciting races of the season after many top drivers started near the back of the grid after the qualifying in variable weather. McLaren driver Kimi Räikkönen won the race after starting from 17th place, overtaking Renault driver Giancarlo Fisichella at the beginning of the last lap – after Fisichella was blocked by a backmarker. At the 2006 event, Michael Schumacher led until an engine failure virtually ended his chances of an eighth championship, which went to Spaniard Fernando Alonso.

Fuji redevelopment

It was announced on 24 March 2006 by the FIA that future races will again be held at the redesigned Fuji Speedway (now owned by Toyota) in Oyama, Sunto District, Shizuoka Prefecture.[7] The news of the Japanese Grand Prix moving to the circuit redesigned by Hermann Tilke was met with some trepidation, as the Honda-owned Suzuka was a favorite of many of the drivers and Hermann Tilke's tracks had received mixed reviews from the drivers and the fans.

On 8 September 2007, it was announced that Fuji will alternate the Japanese Grand Prix with Suzuka, starting from 2009 onwards.[8] The 2007 race was held in torrential rain and started behind the safety car. Lewis Hamilton took the victory while his McLaren teammate Fernando Alonso crashed heavily. Heikki Kovalainen finished 2nd, his best result until that date and Kimi Räikkönen 3rd, marking the first time that two Finnish drivers were together on the podium. In 2008, the first corner brought trouble for both the title contending McLarens and Ferraris, and Fernando Alonso was able to take the victory in a Renault. Felipe Massa was 7th after a penalty for a collision with title rival Lewis Hamilton, while Hamilton finished outside the points, having also served a penalty for an incident in the first corner.

Return to Suzuka

In July 2009, Toyota cited a global economic slump as the reason that the Japanese Grand Prix would not return to Fuji Speedway in 2010 and beyond. The speedway argued, according to the Associated Press, that "continuing to host F1 races could threaten the survival of the company". As a result, the 2010 Grand Prix was held at Suzuka, at which point it was announced that Suzuka would have exclusive hosting duties.[9]

Both the 2009 and 2010 races were dominated by Red Bull and Sebastian Vettel, with Red Bull finishing 1-2 both years. Sebastian Vettel secured his second World Championship in the 2011 Grand Prix with a third-place finish, while McLaren's Jenson Button (the only driver in the field who had a theoretical chance of beating Vettel to the title) won the race wearing a special tribute helmet to the people affected by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The helmet featured a design in the style of the Japanese flag, and he auctioned the helmet off afterwards to raise money for those caught in unfortunate circumstances during the times of the tsunami earlier that year.

Kamui Kobayashi took third place at the Japanese Grand Prix, after enduring race-long pressure from Jenson Button. Kobayashi became the first Japanese driver to finish on a Formula One podium in Japan in 22 years, after Aguri Suzuki in the 1990 Japanese Grand Prix, and was the third Japanese driver to finish on a Formula One podium after Suzuki and Takuma Sato in the 2004 United States Grand Prix.[10]

The 2013 race was won by Sebastian Vettel for Red Bull, marking his fourth consecutive victory of the season as well as his fourth victory overall at Suzuka. Vettel's teammate Mark Webber, who started the race on pole position, finished second behind his teammate, with Romain Grosjean taking the final podium position for Lotus.

In 2014 a typhoon struck the circuit during the race, causing controversy over the late-afternoon start time not being moved. The race saw both the Mercedes of Nico Rosberg and Lewis Hamilton duel with each other for the lead, with Hamilton ultimately taking victory ahead of his teammate and Sebastian Vettel. However, the race was marred by tragedy. On lap 45, Adrian Sutil in the Force India spun off the track at the Dunlop Curve, and as his car was being recovered by a crane, Jules Bianchi in the Marussia spun off track at the same area and smashed horrifically into the crane. The race was red flagged immediately following the accident as conditions were deemed too dangerous to race. Bianchi was unresponsive to marshals and team radio. He was taken to a nearby hospital, where he was placed into a coma. It was hoped that he would recover, but Bianchi died nine months later due to his injuries. This led to changes to the circuit for the next year, with drainage gutters being created at the Dunlop Curve to allow water to runoff faster during a rainstorm, as well as the moving of a similar crane to prevent accidents such as Bianchi's from occurring in the future.

On 23 August 2013 it was announced that the contract for the Japanese Grand Prix had been extended until 2018.[11] A further extension was announced in August 2018 to keep the race at Suzuka until 2021. But the 2020 edition due to be held on 11 October, was cancelled on 12 June due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[12]

Popularity

From its return to the Formula One calendar in 1987, the Japanese Grand Prix has become one of the most popular with spectators. For the 1990 race, three million fans entered a draw for the 120,000 available tickets, due to the popularity of Honda's world championship successes as an engine supplier to the Williams and McLaren teams, the fact that the country had produced its first full-time F1 driver in Satoru Nakajima, and Ayrton Senna's immense popularity in Japan.[original research?] After Nakajima's retirement in 1991 and Honda's withdrawal from competition the following year, interest went into decline despite the addition of the Pacific Grand Prix to the F1 calendar, an event also held in Japan during the 1994 and 1995 seasons. The 1995 Japanese Grand Prix was the first for which the allocated tickets did not sell out.[13] Subsequently, the appearance of new Japanese drivers such as Takuma Sato and the entry of Honda and Toyota as full manufacturer teams has restored the event to its former popularity. But Honda pulled out of F1 at the end of 2008, citing economic reasons, and Toyota did the same the following year, also citing economic reasons. However, Honda returned to Formula One as an engine supplier for McLaren starting in the 2015 season.

Official names

- 1976: F1 World Championship in Japan[14]

- 1987–1988: Fuji Television Japan Grand Prix[15][16]

- 1989–2009: Fuji Television Japanese Grand Prix[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

- 2010–2015, 2017, 2019: Japanese Grand Prix[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

- 2016: Emirates Japanese Grand Prix[46]

- 2018, 2021: Honda Japanese Grand Prix[47][48]

Winners of the Japanese Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004 | |

| 5 | 2007, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018 | |

| 4 | 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013 | |

| 2 | 1966, 1969 | |

| 1969, 1973 | ||

| 1987, 1991 | ||

| 1988, 1993 | ||

| 1994, 1996 | ||

| 1998, 1999 | ||

| 2006, 2008 |

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 1977, 1988, 1991, 1993, 1998, 1999, 2005, 2007, 2011 | |

| 7 | 1987, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 | |

| 6 | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 | |

| 4 | 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013 | |

| 3 | 1989, 1990, 1995 | |

| 1992, 1994, 1996 | ||

| 2 | 1964, 1967 | |

| 1968, 1969 | ||

| 1973, 1975 | ||

| 1963, 1976 | ||

| 2006, 2008 |

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1998, 1999, 2005, 2007, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 | |

| 10 | 1992, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013 | |

| 8 | 1963, 1964, 1972, 1976, 1977, 1989, 1990, 1993 | |

| 7 | 1987, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 | |

| 3 | 1973, 1975, 1976 | |

| 2 | 1988, 1991 |

* Between 1998 and 2005 built by Ilmor

** Built by Cosworth

By year

References

- ^ "Fuji signs deal for 2007". grandprix.com. 14 March 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ Toyota's Fuji Speedway Cancels Formula One Grand Prix From 2010 Archived 28 July 2012 at archive.today Bloomberg.com, Retrieved 22 December 2009

- ^ "Japanese Grand Prix to remain at Suzuka". BBC Sport. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ a b Former Lotus boss Peter Warr dies, autoweek.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "Sport". The Guardian. London. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2010. [dead link]

- ^ Video on YouTube[dead link]

- ^ "Suzuka loses Japanese GP to Fuji". BBC News. 24 March 2006. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Japanese Grand Prix to alternate between Fuji and Suzuka". www.formula1.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "Toyota to pull out of hosting 2010 Japan GP". Mainichi Daily News. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan; Beer, Matt (7 October 2012). "Kamui Kobayashi celebrates 'amazing' podium". Autosport. Haymarket Publications. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

Kobayashi's result equalled the best ever finish for Japanese drivers in Formula 1 – achieved by Aguri Suzuki at Suzuka in 1990 and Takuma Sato at Indianapolis in 2004.

- ^ "Suzuka to remain on F1 calendar until at least 2018". autosport.com. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "F1 confirm 2020 Azerbaijan, Singapore and Japanese Grands Prix have been cancelled". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Domenjoz, Luc (1995). "The 17 Grand Prix – Fuji Television Japanese Grand Prix". Formula 1 Yearbook 1995. Chronosports Editeur. p. 203. ISBN 2-940125-06-6.

- ^ "1976 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1989 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1990 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1992 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1999 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2000 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2001 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2003 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2004 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2005 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2006 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2007 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2009 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2010 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2011 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2012 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2013 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2014 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2015 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2017 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2019 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2016 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "2018 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "Japan". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ GP Japan, 3.5.1963, www.racingsportscars.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "第1回日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "第1回日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ a b Brabham BT9, www.oldracingcars.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ a b "第2回日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Prince R380-I (1966 : R380), www.nissan-global.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "第3回日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ GP Japan, 3.5.1967, www.racingsportscars.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "第4回日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ GP Japan, 3.5.1968, www.racingsportscars.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "日本グランプリ". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ GP Japan, 10.10.1969, www.racingsportscars.com Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "日本グランプリ自動車レース大会". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ COLT F2000, www.mitsubishi-motors.co.jp Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 June 2017

- ^ "日本グランプリ". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "日本グランプリ". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "日本グランプリ". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "日本グランプリ". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "日本グランプリ自動車レース". Japan Automobile Federation. Retrieved 9 May 2021.