Lindbergh kidnapping

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 22, 1930 |

| Died | March 2, 1932 (aged 1) |

| Cause of death | Blow to the head (crushed skull)[1] |

| Body discovered | May 12, 1932, in Hopewell, New Jersey |

| Resting place | Ashes scattered in the Atlantic Ocean |

| Nationality | US |

| Other names | Lindbergh baby |

| Known for | Kidnapped victim |

The kidnapping of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the eldest son of aviator Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was one of the most sensational crimes of the 20th century. The 20-month-old toddler was abducted from his family home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey, on the evening of March 1, 1932.[2] Over two months later, on May 12, 1932, his body was discovered a short distance from the Lindberghs' home in neighboring Hopewell Township.[3] A medical examination determined that the cause of death was a massive skull fracture.[4]

After an investigation that lasted more than two years, Richard Hauptmann was arrested and charged with the crime. In a trial that was held from January 2 to February 13, 1935, Hauptmann was found guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced to death. He was executed by electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison on April 3, 1936. Hauptmann proclaimed his innocence to the end, and many historians question his guilt.[5]

Newspaper writer H. L. Mencken called the kidnapping and subsequent trial "the biggest story since the Resurrection."[6][7] Legal scholars have referred to the trial as one of the "trials of the century".[8]The crime spurred Congress to pass the Federal Kidnapping Act, commonly called the "Lindbergh Law," which made transporting a kidnapping victim across state lines a federal crime.[9]

The crime

At 8:00 pm on March 1, 1932, the nurse of the family, Betty Gow, put 20-month-old Charles Lindbergh, Jr. to bed in his crib. She wrapped the baby in a blanket and fastened it with two large pins to prevent him from moving during sleep. Around 9:30 pm, Charles Lindbergh, the baby's father, heard a noise that made him think that the slats from the full orange crate in the kitchen had broken off and fallen. However, at 10:00 pm, Gow returned to the baby's bedroom to discover that he was not in his crib. She asked Anne Lindbergh, who had just come out of her bath, if the baby was with her.

Not finding the infant with his mother, the nurse came downstairs to talk with Lindbergh, who was in the library just below the baby's room in the southeast corner of the house. He went immediately to the child's room to see for himself that the baby was gone. As he searched the room, he found a note in a white envelope on the window sill above the radiator.

Lindbergh grabbed his gun and went around the house looking for intruders. In 20 minutes, the local police were on the way to the home, along with the media and the family's lawyer. Later that night, one tire print was discovered in the mud caused by the rainy weather conditions earlier that day. Shortly after the police had begun searching near the perimeter of the house, they discovered three pieces of a ladder in a nearby bush that appeared intelligently designed but crudely constructed.

The investigation

First on the scene was Chief Harry Wolfe of the nearby Hopewell Borough police. Wolfe was soon joined by New Jersey State Police officers. The police searched the home and scoured the surrounding area for miles.

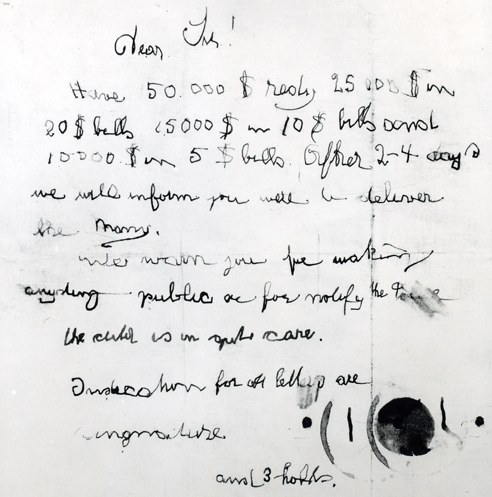

After midnight, a fingerprint expert arrived at the home to examine the note left on the window sill and the ladder. The ladder had 400 partial fingerprints and some footprints left behind. However, most were of no value to the investigation due to the surge of media and police that were present within the first 30 to 60 minutes after the first call for help. During the fingerprint discovery process, not a single adult fingerprint was found in the room, including in areas the key witnesses admitted to touching, such as the probable entry window. Fingerprints of the baby were found on the lower areas of the room. The ransom note that was found by Lindbergh was opened and read by the police after they arrived. The brief, handwritten letter was riddled with spelling mistakes and grammatical irregularities:

The note

Dear Sir!

Have 50.000$ redy [sic] 25 000$ in

20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and

10000$ in 5$ bills After 2–4 days

we will inform you were [sic] to deliver

the money.

We warn you for making

anyding [sic] public or for notify the Police

The child is in gut [sic] care.

Indication for all letters are

Singnature [sic] [Symbol to right]

There were two interconnected blue circles surrounding a red circle below the message, with a hole punched through the red circle and two other holes punched outside the circles.

The news spreads

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly, and, along with police, the well-connected and well-intentioned arrived at the Lindbergh estate. There were military colonels offering their aid, though only one had law enforcement expertise: Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were Henry Skillman Breckinridge, a Wall Street lawyer; William J. Donovan (a.k.a. "Wild Bill" Donovan, a hero of the First World War who would later head the OSS). Lindbergh and these men believed that the kidnapping was perpetrated by organized crime figures. The letter, they thought, seemed written by someone who spoke German as his native language. Charles Lindbergh, at this time, used his influence to control the direction of the investigation.[11]

They contacted Mickey Rosner, a Broadway hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner, in turn, brought in two speakeasy owners: Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob. Several organized crime figures – notably Al Capone, Willie Moretti, Joe Adonis and Longy Zwillman — spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby to his family in exchange for money or for legal favors. Specifically, Capone offered assistance in return for being released from prison under the pretense that his assistance would be more effective. This was quickly denied by the authorities.

The morning after the kidnapping, U.S. President Herbert Hoover was notified of the crime. Though the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement (kidnapping then being classified as a local crime), Hoover declared that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child.[citation needed]

The Bureau of Investigation (not yet called the FBI) was authorized to investigate the case, while the United States Coast Guard, the U.S. Customs Service, the U.S. Immigration Service and the Washington, D.C., police were told their services might be required. New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little Lindy." The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. The total reward of $75,000 was made even more significant by the fact that the offer was made during the early days of the Great Depression.

During this time, Lindbergh flew to Round Hill Airport in order to investigate a lead that specified that the whereabouts of his son was on a boat off of the Elizabeth Islands.[12]

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter arrived at the Lindbergh home via the mail. Postmarked in Brooklyn, the letter was genuine, carrying the perforated red and blue marks.

A second ransom note then arrived by mail, also postmarked from Brooklyn. Then, a third letter was mailed. It too came from Brooklyn. This letter warned that since the police were now involved in the case, the ransom had been raised to $70,000.

John Condon

During this time, a well-known Bronx personality and retired school teacher, John F. Condon [13] wrote a letter to the Bronx Home News,[14] offering $1,000 if the kidnapper would turn the child over to a Catholic priest. Condon received a letter reportedly written by the kidnappers. It authorized Condon to be their intermediary with Lindbergh.[15] Lindbergh accepted the letter as genuine.

Following the latest letter's instructions, Condon placed a classified ad in the New York American reading: "Money is Ready. Jafsie". Condon then waited for further instructions from the culprits.[14]

A meeting between "Jafsie" and a representative of the group that claimed to be the kidnappers was eventually scheduled for late one evening at Woodlawn Cemetery. According to Condon, the man sounded foreign but stayed in the shadows during the conversation, and he was thus unable to get a close look at his face. The man said his name was John, and he related his story: he was a "Scandinavian" sailor, part of a gang of three men and two women. The Lindbergh child was unharmed and being held on a boat, but the kidnappers were still not ready to return him without a payment of the ransom. When Condon expressed doubt that "John" actually had the baby, he promised some proof: the kidnapper would soon return the baby's sleeping suit. The stranger asked Condon, "... would I 'burn' (be executed), if the package (baby) were dead?" When questioned further, he assured Condon that the baby was alive.

On March 16, John Condon received a package by mail that contained a toddler's sleeping suit, which was sent as proof of their claim, and a seventh ransom note.[1] Condon showed the sleeping suit to Lindbergh, who identified it as belonging to his son. After the delivery of the sleeping suit, Condon took out a new ad in the Home News declaring, "Money is ready. No cops. No secret service. I come alone, like last time." One month after the child was kidnapped, on April 1, Condon received a letter from the reported kidnappers. They were ready to accept payment.

Payment of the ransom

The ransom was packaged in a wooden box that was custom-made in the hope that it could later be identified. The ransom money itself was made up with a number of gold certificates that were to be withdrawn from circulation in the near future.[1] It was hoped that anyone passing large amounts of gold notes would draw attention to himself and help aid in identifying the abductors.[5][16] Also, while the bills themselves were not marked, the serial number of each bill was recorded. Some sources credit Frank J. Wilson for pressing for this[17] while others credit Elmer Lincoln Irey.[18][19]

The next evening, April 2, Condon was given a note by an unknown cab driver. Condon met "John" and told him that they had been able to raise only $50,000. The man accepted the money and gave Condon a note. The child was supposedly in the care of two women who, according to the note, were innocent.

Discovery of the body

On May 12, delivery truck driver William Allen pulled his truck to the side of a road about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of Mount Rose in neighboring Hopewell Township.[3] He went to a grove of trees to relieve himself, and there he discovered the body of a toddler.[20] Allen notified the police, who took the body to a morgue in nearby Trenton, New Jersey. The body was badly decomposed, and it was discovered that the skull was badly fractured. The body looked like it had been chewed on and attacked by various animals as well as indications that someone had made an attempt to hastily bury the body.[4][20] Lindbergh and Gow quickly identified the baby as the missing infant based on the overlapping toes of the right foot and the shirt that Gow had made for the baby. They surmised that the child had been killed by a blow to the head. The father was insistent on having the body cremated afterward.[21]

Once the U.S. Congress learned that the child was dead, legislation was rushed through making kidnapping a federal crime. The FBI could now aid the case more directly. (In fact, as the victim had not been transported across a state line, the law did not technically apply to the Lindbergh case.)

In June 1932, officials began to suspect an "inside job" perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs trusted. Suspicions fell upon Violet Sharp, a British household servant at the Morrow home. She had given contradictory testimony regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned. She committed suicide on June 10, 1932,[22] by ingesting a silver polish that contained potassium cyanide just prior to what would have been her fourth time being questioned.[23][24] After her alibi was confirmed, it was later determined that the possible threat of losing her job and the intense questioning had driven her to commit suicide. At the time, the police investigators were criticized for what some felt were the "heavy handed" police tactics used.[25]

Following the death of Violet Sharp, John Condon was also questioned by police. Condon's home was searched as well, but nothing was found that tied Condon to the crime. Charles Lindbergh stood by Condon during this time as well.[26]

John Condon's unofficial investigation

After the discovery of the body, Condon remained unofficially involved in the case. To the public, he had become a suspect and in some circles vilified.[27] For the next two years, he visited police departments and pledged to find "Cemetery John".

Condon's actions regarding the case were increasingly flamboyant. On one occasion, while riding a city bus, he saw a suspect and, announcing his secret identity, ordered the bus to a stop. The startled driver complied, and Condon darted from the bus, though Condon's target eluded him. Condon's actions were also criticized as exploitative when he agreed to appear in a vaudeville act regarding the kidnapping.[28] Liberty magazine published a serialized account of Condon's involvement in the Lindbergh kidnapping under the title "Jafsie Tells All".[29]

Tracking the ransom money

Investigation of the case was soon in the doldrums. There were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A pamphlet was prepared with the serial numbers on the ransom bills, and 250,000 copies were distributed to businesses mainly in New York City.[1][16] A few of the ransom bills turned up in scattered locations, some as far away as Chicago and Minneapolis, but the people spending them were never found.

As per Executive Order 6102, Gold Certificates were to be turned in by May 1, 1933.[30] A few days before the deadline, a man in Manhattan brought in $2,980 of the ransom money to be exchanged. The bank was busy and no one could remember anything specific about the person. He had filled out a required form, which gave his name as J. J. Faulkner. The address supplied was 537 West 149th Street in New York City.[16]

When authorities visited the address, they learned that no one named Faulkner had lived there – or anywhere nearby – for many years. U.S. Treasury officials kept looking and eventually learned that a woman named Jane Faulkner had lived at the address in question in 1913. She had moved after she married a German man named Giessler. The couple was tracked down, and both denied any involvement in the crime.[citation needed]

Capture of a suspect

For thirty months, New York Police Detective James J. Finn and FBI Agent Thomas Sisk had been working on the Lindbergh case. They had been able to track down many bills from the ransom money that were being spent in places throughout New York City. A map created by Finn recorded each find and eventually showed that many of the bills were being passed mainly along the route of the Lexington Avenue subway. This subway line connected the East Bronx with the east side of Manhattan, including the German-Austrian neighborhood of Yorkville.[5]

On September 18, 1934, a gold certificate from the ransom money was referred to Detective Finn and Agent Sisk.[5] Although President Roosevelt had issued an executive order on April 5, 1933, calling for all gold certificates to be turned in by May 1, 1933, under the penalty of fine or imprisonment,[30] some members of the public held on to them past the deadline.[31] The ten dollar gold certificate was discovered by a teller of the Corn Exchange Bank at 125th Street and Park Avenue in Manhattan.[1] It had a New York license plate, 4U-13-41-N.Y, penciled in the margin, which helped the investigators trace the bill to a nearby gas station. The station manager, Walter Lyle, had written down the license plate number feeling that his customer was acting "suspicious" and was "possibly a counterfeiter".[1][5][16][32]

It was found that the license plate number belonged to a blue Dodge sedan owned by Richard Hauptmann of 1279 East 222nd Street in the Bronx.[5] Hauptmann was found to be a German immigrant with a criminal record in his homeland. When Hauptmann was arrested, he had on his person a twenty dollar gold certificate.[1][5] A search by police of Hauptmann's garage found over $14,000 of the ransom money. During the police investigation, the garage that Hauptmann had built was torn down in the search for the money.[33]

Hauptmann was arrested by Finn; he was interrogated, as well as beaten at least once, throughout the day and night that followed.[16] The money, Hauptmann stated, along with other items, had been left with him by friend and former business partner Isidor Fisch. Fisch had died on March 29, 1934, shortly after returning to Germany.[5] Only following Fisch's death, Hauptmann stated, did he learn that the shoe box left with him contained a considerable sum of money. He took the money because he claimed that it was owed to him from a business deal that he and Fisch had made.[5] Hauptmann consistently denied any connection to the crime or knowledge that the money in his house was from the ransom.

In the search of his apartment by police, a considerable amount of additional evidence that he was involved in the crime surfaced. One item was a notebook that contained a sketch for the construction of a ladder similar to that which was found at the Lindbergh home in March 1932. John Condon's telephone number, along with his address, were discovered written down on a closet wall in the house. A key piece of evidence, a piece of wood, was discovered in the attic of the home. After being examined by an expert, it was determined to be an exact match to the wood used in the construction of the ladder found at the scene of the crime.

Hauptmann was indicted in the Bronx on September 24, 1934, for extorting the $50,000 ransom from Charles Lindbergh.[5] Two weeks later, on October 8, 1934, Hauptmann was indicted in New Jersey for the murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr.[1] Two days later, he was surrendered to New Jersey authorities by New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman to face charges directly related to the kidnapping and murder of the child. Hauptmann was moved to the Hunterdon County Jail in Flemington, New Jersey, on October 19, 1934.[1]

The trial

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder, meaning that conviction could result in the death penalty. He pleaded not guilty. Held at the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, New Jersey, the trial soon became a sensation: reporters swarmed the town, and every hotel room was booked.

In exchange for rights to publish Hauptmann's story in their newspaper, Edward J. Reilly was hired by the Daily Mirror to serve as Hauptmann's attorney. David T. Wilentz, Attorney General of New Jersey, led the prosecution.

In addition to Hauptmann's possession of over $14,000 of the ransom money, the State introduced evidence showing a striking similarity between Hauptmann's handwriting and the handwriting on the ransom notes. Eight different handwriting experts (Albert S. Osborn, Elbridge W. Stein, John F. Tyrrell, Herbert J. Walter, Harry M. Cassidy, Wilmer T. Souder, Albert D. Osborn, and Clark Sellers)[34] were called by the prosecution to the witness stand, where they pointed out similarities between words and letters in the ransom notes and in Hauptmann's writing specimens (which included documents written before he was arrested, such as automobile registration applications). One expert (John M. Trendley) was called by the defense to rebut this evidence, while two others (Samuel C. Malone and Arthur P. Meyers) declined to testify at the trial.[34] The latter two demanded $500 for their services before even looking at the notes and were promptly dismissed when assisting local Flemington attorney C. Lloyd Fisher declined to render such an amount.[35]

Based on the forensic work of Arthur Koehler at the Forest Products Laboratory, the State also introduced photographic evidence demonstrating that the wood from the ladder left at the crime scene matched a plank from the floor of Hauptmann's attic: the type of wood, the direction of tree growth, the milling pattern at the factory, the inside and outside surface of the wood, and the grain on both sides were identical, and two oddly placed nail holes lined up with a joist splice in Hauptmann's attic. Additionally, the prosecutors noted that Condon's address and telephone number had been found written in pencil on a closet door in Hauptmann's home. Hauptmann himself admitted in a police interview that he had written Condon's address on the closet door: "I must have read it in the paper about the story. I was a little bit interested and keep a little bit record of it, and maybe I was just on the closet, and was reading the paper and put it down the address." When asked about Condon's telephone number, he could respond only, "I can't give you any explanation about the telephone number."

The defense did not challenge the identification of the body, a common practice in murder cases at the time designed to avoid exposing the jury to an intense analysis of the body and its condition.

Condon and Lindbergh both testified that Hauptmann was "John". Another witness, Amandus Hochmuth, testified that he saw Hauptmann near the scene of the crime.

Hauptmann was ultimately convicted of the crimes and sentenced to death. His appeals were rejected, though New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman granted a temporary reprieve of Hauptmann's execution and made the politically unpopular move of having the New Jersey Board of Pardons review the case. They found no reason to issue a pardon.

Hauptmann turned down a large offer from a Hearst newspaper for a confession and refused a last-minute offer to commute his execution to a life sentence in exchange for a confession. He was electrocuted on April 3, 1936, just over four years after the kidnapping.

Following Hauptmann's death, some reporters and independent investigators came up with numerous questions regarding the way the investigation was run and the fairness of the trial. Questions were raised concerning issues ranging from witness tampering to the planting of evidence. Twice during the 1980s, Anna Hauptmann sued the state of New Jersey for the unjust execution of her husband. Both times the suits were dismissed on unknown grounds.

Controversy

Like other notorious crimes, the Lindbergh kidnapping has attracted hoaxes and alternative theories.

Review of the evidence

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Erastus Mead Hudson was a fingerprint expert who knew the then-rare silver nitrate process of collecting fingerprints off wood and other surfaces on which the previous powder method could not detect fingerprints. He found that Hauptmann's fingerprints were not on the wood, even in places that the man who made the ladder would have had to touch. Upon reporting this to a police officer and stating that they must look further, the officer said, "Good God, don't tell us that, Doctor!" The ladder was then washed of all fingerprints, and Schwarzkopf refused to make it public that Hauptmann's prints were not on the ladder.[36]

Several books have been written proclaiming Hauptmann's innocence. These books variously criticize the police for allowing the crime scenes to become contaminated, Lindbergh and his associates for interfering with the investigation, Hauptmann's trial lawyers for ineffectively representing him, and the reliability of the witnesses and the physical evidence presented at the trial. Ludovic Kennedy, in particular, questioned much of the evidence, such as the origin of the ladder and the testimony of many of the witnesses. A recent book on the case, A Talent to Deceive by British investigative writer William Norris, not only declares Hauptmann's innocence but also accuses Lindbergh of a cover-up of the killer's true identity. The book points the finger of blame at Dwight Morrow, Jr., Lindbergh's brother-in-law.[citation needed] However, no proof is offered.

At least one modern author disagrees with these theories. Jim Fisher, a former FBI agent and professor at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania,[37] has written two books on the subject, The Lindbergh Case (1987)[38] and The Ghosts of Hopewell (1999)[39] to address, at least in part, what he calls a "revision movement" regarding the case.[40] In these texts, he provides an interpretation discussing both the pros and cons of the evidence presented at trial. He summarizes his conclusions thus: "Today, the Lindbergh phenomena [sic] is a giant hoax perpetrated by people who are taking advantage of an uninformed and cynical public. Notwithstanding all of the books, TV programs, and legal suits, Hauptmann is as guilty today as he was in 1932 when he kidnapped and killed the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lindbergh."[41]

A more recent book, Hauptmann's Ladder: A Step-by-Step Analysis of the Lindbergh Kidnapping, by Richard T. Cahill Jr., concludes that Hauptmann was guilty but questions whether he should have been executed. Though Cahill concludes that Hauptmann likely acted alone, he acknowledges the possibility of an accomplice.

In 2005, the truTV television program Forensic Files conducted a re-examination of the physical evidence in the kidnapping using more modern scientific techniques. Kelvin Keraga concluded that the ladder used in the kidnapping was made from wood that had previously been part of Hauptmann's attic.[42] Three forensic document examiners, Grant Sperry, Gideon Epstein, and Peter E. Baier, PhD, worked independently of each other. Sperry concluded that it was "highly probable" that the kidnapper's notes were written by Hauptmann.[43] Epstein concluded that "there was overwhelming evidence that the notes were written by one person and that one person was Richard Bruno Hauptmann."[44]

Baier wrote that Hauptmann "probably" wrote the notes, but Baier said, "Looking at all these findings, no definite and unambiguous conclusion can be drawn."[45] The program concluded that Hauptmann had indeed been guilty but it noted that many questions remained, such as how he could have known that the Lindberghs would be remaining home during the week.[citation needed]

Alternate theories of the case are nothing new. According to John Reisinger in Master Detective (Citadel Press, 2006), famed New Jersey detective, Ellis Parker, conducted an independent investigation in 1936 and obtained a signed confession from former Trenton attorney Paul Wendel, creating a sensation and resulting in a temporary stay of execution for the convicted Bruno Hauptmann. The case against Wendel collapsed, however, when Wendel insisted his confession had been coerced. [46]

Several authors have suggested that Charles Lindbergh, the father, was responsible for the kidnapping. In 2010, Jim Bahm, author of the book Beneath the Winter Sycamores about the Lindbergh kidnapping, implied that the baby was physically disabled and Charles Lindbergh wanted to have someone else raise the child in Germany. In the book, after 10 days, the baby died of pneumonia, and the kidnapping plot blew up in Lindbergh's face.[47]

Robert Zorn's 2012 book, Cemetery John, proposes that Hauptmann was the foot soldier in a conspiracy with two other German-born men, John and Walter Knoll. Zorn's father, economist Eugene Zorn, had been investigating an incident from his teen years that convinced him he had witnessed the conspiracy being discussed. After the elder Zorn's death, son Robert continued the investigation.[48]

As represented in the arts

- In music

- May 1932: Just one day after the Lindbergh baby was discovered murdered, the prolific country recording artist Bob Miller (under the pseudonym Bob Ferguson) recorded two songs for Columbia on May 13, 1932, commemorating the event. The songs were released on Columbia 15759-D with the titles "Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr." and "There's a New Star Up in Heaven (Baby Lindy Is Up There)".[49]

- January 1935: Goebel Reeves recorded his song “The Kidnapped Baby,” released later that year.[citation needed]

- In novels

- January 1934: Agatha Christie was inspired by circumstances of the case when she described the kidnapping of baby girl Daisy Armstrong in her 1934 Hercule Poirot novel Murder on the Orient Express, including a parallel of the death of Violet Sharpe.[citation needed]

- 1981: The kidnapping and its aftermath served as the inspiration for Maurice Sendak's book Outside Over There.[citation needed]

- 1991: Stolen Away by Max Allan Collins is a thorough treatment of the case from the point of view of a fictional detective. The author examines several possible solutions and provides considerable support for one.[citation needed]

- 2004: In Philip Roth's novel The Plot Against America, the narrator describes theories about the kidnapping – most notably, the possibility that prominent Nazis were responsible and used the kidnapping to extort the Lindberghs into expressing some admiration for and defense of the policies of Nazi Germany. According to this theory (which the narrator neither accepts nor rejects), the baby is brought to Germany where he is adopted into a Nazi family and becomes a member of the Hitler Youth, unaware of his true background.[citation needed]

- 2012: The Last Newspaperman, by Mark Di Ionno, tells the story from the perspective of a tabloid journalist who covered the kidnapping and claims to have heard an off-the-record confession by Bruno Hauptmann.[citation needed]

- James Merrill wrote a poem called "Days of 1935" in which he talks about the Lindbergh kidnapping from the child's point of view.[citation needed]

- In languages

- In Spanish, the expression "Estar más perdido que el hijo de Lindbergh" (to be more lost than Lindbergh's child) means "to be clueless"

- In film/television

- 1976: In the television movie The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case, Anthony Hopkins played the role of Bruno Hauptmann, and Sian Barbara Allen played Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

- 1996: The Lindbergh kidnapping was the subject of a 1996 Golden Globe- and Emmy-nominated HBO TV movie titled Crime of the Century. Bruno Hauptmann was played by Stephen Rea and his wife Anna by Isabella Rossellini.

- 2009: In the documentary Tell Them Anything You Want, author/illustrator Maurice Sendak tells interviewer Spike Jonze that he has been obsessed with the case of the Lindbergh baby since he was two years old.[citation needed]

- 2011: The Clint Eastwood-directed film, J. Edgar. includes reference to the Lindbergh kidnapping. Josh Lucas plays Charles Lindbergh, Damon Herriman was cast as Bruno Hauptmann and Stephen Root was cast as Arthur Koehler, an expert on wood who testified at the trial.[50]

- 2013: On July 31 the PBS program Nova aired "Who Killed Lindbergh's Baby?", an investigation conducted by the former FBI forensics expert, John Douglas. Douglas explores the incident and trial of Hauptmann, then goes further to investigate various theories about who else was likely to have been an accomplice.[51]

- In theatre

- The musical Baby Case dramatizes the events of the Lindbergh trial and the media circus that surrounded it.[52]

- June 2002: The Opera Theatre of St. Louis premiered a new opera by the American composer, Cary John Franklin, entitled "Loss of Eden." The opera commemorated the centennial of Lindbergh's birth, and the 75th anniversary of his Atlantic crossing, and was a musical reflection on Lindbergh's public triumph and personal tragedy. Later, the composer reworked some of the music into a chamber work entitled "Falls Flyer." The music in the opening section of the piece is derived from the music in the major dramatic moments of the opera—the plane departing for Paris, the kidnapping, and the execution of Bruno Hauptmann.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Lindbergh Kidnapping". FBI History – Famous Cases. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Gill, Barbara (1981). "Lindbergh kidnapping rocked the world 50 years ago". The Hunterdon County Democrat. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

So while the world's attention was focused on Hopewell, from which the first press dispatches emanated about the kidnapping, the Democrat made sure its readers knew that the new home of Col. Charles A. Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh was in East Amwell Township Hunterdon County.

- ^ a b "Lindbergh Kidnapping Index". Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Aiuto, Russell. "The Theft of the Eaglet". The Lindbergh Kidnapping. TruTv. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Linder, Douglas (2005). "The Trial of Richard "Bruno" Hauptmann: An Account". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Notorious Murders; CrimeLibrary.com; accessed August 2015

- ^ Newton, Michael (2012). The FBI Encyclopedia. NC, USA: McFarland. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7864-6620-7.

- ^ Ph.D, Frankie Y. Bailey; Ph.D, Steven Chermak (October 30, 2007). Crimes and Trials of the Century [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 167. ISBN 9781573569736.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (March 26, 2007). "This Day on Capitol Hill: February 13". The Politico. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Robert Zorn (2012). Cemetery John: The Undiscovered Mastermind of the Lindbergh Kidnapping. The Overlook Press. p. 68. ISBN 9781590208564.

- ^ Fass, Paula S. (1997). "The Nation's Child...is Dead":The Lindbergh Case page 100. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Southeastern Massachusetts". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. December 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Note: "Jafsie" was a pseudonym based on a phonetic pronunciation of Condon's initials, "J.F.C."

- ^ a b Maeder, Jay (September 23, 1999). "Half Dream Jafsie". Daily News. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ Aiuto, Russell. "Parallel Threads, Continued". The Lindbergh Kidnapping. TruTv. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Manning, Lona (March 4, 2007). "The Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping". Crime Magazine. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Eig, Jonathan (2010). Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America's Most Wanted Gangster. Simon and Schuster. p. 372. ISBN 9781439199893.

- ^ Waller, George (1961). Kidnap: The Story of the Lindbergh Case. Dial Press. p. 71.

- ^ Robert G. Folsom (2010). "The Money Trail: How Elmer Irey and His T-Men Brought Down America's Criminal Elite". Potomac Books. pp. 217–219.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b "CRIME: Never-to-be-Forgotten". Time Magazine. May 23, 1932. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "Murdered Child's Body Now Reduced to Pile of Ashes". The Evening Independent. May 14, 1932.

- ^ "Morrow Maid Balks Inquiry". www.lindberghkidnappinghoax.com. June 10, 1932.

- ^ Lindbergh, Anne; Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead; San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1973.

- ^ Falzini, Mark W. (April 2006). "Violet Sharp Collection page 20" (PDF). Studying the Lindbergh Case – A Guide to the Files and Resources Available at the New Jersey State Police Museum. The New Jersey State Police. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Lindbergh Kidnapping". The Biography Channel UK. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Lindbergh Kidnapping". The Biography Channel UK. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "Lindbergh Baby Booty: The missing ransom money may still be up there". New York Press. March 11, 2003. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "Ministers Protest Billing of Condon; 25 See Jafsie Vaudeville Act Scheduled for Plainfield as Tragic Exploitation". The New York Times. January 5, 1936. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "Milestones Jan. 15, 1945". Time Magazine. January 15, 1945. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Woolley, John; Gerhard Peters. "34 – Executive Order 6102 – Requiring Gold Coin, Gold Bullion and Gold Certificates to Be Delivered to the Government April 5, 1933". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ "FAQs: Currency – Buying, Selling & Redeeming". United States Department of the Treasury. June 25, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ "National Affairs: 4U-13-41". Time Magazine. October 1, 1934. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "National Affairs Oct. 8, 1934". Time Magazine. October 8, 1934. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Fisher, Jim (September 1, 1994). The Lindbergh Case. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2147-5.

- ^ Gardner, Lloyd C. (2004). The Case That Never Dies. Rutgers University Press. p. 336. ISBN 0-8135-3385-6.

- ^ Lloyd G. Gardner, The case that never dies, p. 344

- ^ Fisher, Jim. "Biography". Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Jim (1994) [1987]. The Lindbergh Case. Rutgers University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0-8135-2147-5.

- ^ Fisher, Jim (1999). The Ghosts of Hopewell: Setting the Record Straight in the Lindbergh Case. Southern Illinois Univ Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-8093-2285-4.

- ^ Fisher, Jim. "The Lindbergh Case: A Look Back to the Future – Page 3 of 3". Retrieved April 29, 2011.

For the Lindbergh case, the revisionist movement began in 1976 with the publication of a book by a tabloid reporter named Anthony Scaduto. In Scapegoat, Scaduto asserts that the Lindbergh baby was not murdered and that Hauptmann was the victim of a mass conspiracy of prosecution perjury and fabricated physical evidence.

- ^ Fisher, Jim. "The Lindbergh Case: How Can Such a Guilty Kidnapper be so Innocent? – Page 3 of 3". Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Testimony in Wood, Summary Report 1.2; 2005; pp. 10, 32

- ^ Forensic Document Examination Services, Inc. Report 04-0828; p 2

- ^ Gideon Epstein Forensic Document Examination Report; January 25, 2005; p 3

- ^ Peter D. Baier Expert Opinion; February 25, 2005; p 7

- ^ Master Detective – Americas Real-life Sherlock; book search

- ^ Beneath-Winter-Sycamores; Bahm, Jim;

- ^ Edward Colimore (July 8, 2012). "Tale of a Lindbergh conspiracy draws attention". The Inquirer. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Russell, Tony. Country music records: a discography, 1921–1942. Oxford University Press US, 2004. p.621.

- ^ Rich, Katey. "Stephen Root Will Play A Wood Expert In Clint Eastwood's J. Edgar". Cinema Blend. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ "Who Killed Lindbergh's Baby?". Nova. July 31, 2013. PBS/WGBH, Boston. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ Baby Case; web archive

Bibliography

- Ahlgren, Gregory and Stephen Monier, Crime of the Century:The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax, Branden Books, 1993, ISBN 0-8283-1971-5

- Cahill, Richard T. Jr., Hauptmann's Ladder: A Step-by-Step Analysis of the Lindbergh Kidnapping, Kent State University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1-60635-193-2

- Fisher, Jim, The Lindbergh Case, Rutgers University Press, Reprint 1994, ISBN 0-8135-2147-5

- Fisher, Jim, The Ghosts of Hopewell: Setting the Record Straight in the Lindbergh Case, Southern Illinois University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8093-2717-1

- Kennedy, Sir Ludovic, The Airman And The Carpenter, 1985, ISBN 0-670-80606-4

- Kurland, Michael, A Gallery of Rogues: Portraits in True Crime, Prentice Hall General Reference, 1994, ISBN 0-671-85011-3

- Newton, Michael, The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes, Checkmark Books, 2004, ISBN 0-8160-4981-5

- Norris, William, A Talent to Deceive, SynergEbooks, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7443-1594-3

- Reisinger, John, Master Detective (Ellis Parker's independent investigation), Citadel Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8065-2750-5

External links

- Photographic Evidence from the trial on the New Jersey State Archives Website

- New Jersey police museum at West Trenton which holds evidence of the kidnapping

- Lindbergh Kidnapping and other Top 25 Crimes of the Century at Time.com

- Documents, information and a Discussion Group on the LKC: crime and trial

- More about the Lindbergh kidnapping

- The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax --- dissenting views on the trial

- FBI History – Famous Cases – The Lindbergh Kidnapping

- Lindbergh Case Chronology

- Famous American Trials – Richard Hauptmann (Lindbergh Kidnapping) Trial

- Current photographs of places connected with the Lindbergh kidnapping

- Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

- CSI Madison, Wisconsin: Wooden Witness