Long take

In filmmaking, a long take or oner is an uninterrupted shot in a film which lasts much longer than the conventional editing pace either of the film itself or of films in general, usually lasting several minutes. Long takes are often accomplished through the use of a dolly shot or Steadicam shot. Long takes of a sequence filmed in one shot without any editing are rare in films.[1]

Background

The term "long take" is used because it avoids the ambiguous meanings of "long shot", which can refer to the framing of a shot, and "long cut", which can refer to either a whole version of a film or the general editing pacing of the film. However, these two terms are sometimes used interchangeably with "long take".

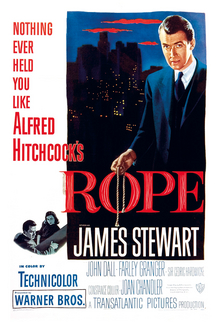

When filming Rope (1948), Alfred Hitchcock intended for the film to have the effect of one long continuous take, but the cameras available could hold no more than 1000 feet of 35 mm film. As a result, each take used up to a whole roll of film and lasts up to 10 minutes. Many takes end with a dolly shot to a featureless surface (such as the back of a character's jacket), with the following take beginning at the same point by zooming out. The entire film consists of only 11 shots.[2] [a]

Andy Warhol and collaborating avant-garde filmmaker, Jonas Mekas, shot the 485-minute-long experimental film, Empire (1964), on 10 rolls of film using an Auricon camera via 16mm film which allowed longer takes than its 35 mm counterpart. "The camera took a 1,200ft roll of film that would shoot for roughly 33 minutes."[4]

The length of a take was originally limited to how much film a camera could hold, but the advent of digital video has considerably lengthened the maximum length of a take. A handful of theatrically released feature films, such as Timecode (2000), Russian Ark (2002), PVC-1 (2007) and The Silent House (2010) are filmed in one single take; others are composed entirely from a series of long takes, while many more may be well known for one or two specific long takes within otherwise more conventionally edited films. In 2012, the art collective The Hut Project produced The Look of Performance, a digital film shot in a single 360° take lasting 3 hours, 33 minutes and 8 seconds. The film was shot at 50 frames per second, meaning the final exhibited work lasts 7 hours, 6 minutes and 17 seconds.[5]

The long take is rarely used in television, though the police procedural series The Bill used it to achieve a documentary style effect.[6] Other examples include The X-Files episode "Triangle" (season 6, episode 3), directed (and written) by the series creator Chris Carter. The technique is also frequently used in ER, which fits with the show's use of Steadicam for the majority of shots. An episode "The Inheritance / C.I.D. 111" of the Indian suspense drama C.I.D., broadcast on November 7, 2004, is a 111-minute-long single take. It currently holds the Guinness World Record for the longest single shot for TV.

Sequence shot

A sequence shot is a long take that constitutes an entire scene. Such a shot may involve sophisticated camera movement. It is sometimes called by the French term plan-séquence. The use of the sequence shot allows for realistic or dramatically significant background and middle ground activity. Actors range about the set transacting their business while the camera shifts focus from one plane of depth to another and back again. Significant off-frame action is often followed with a moving camera, characteristically through a series of pans within a single continuous shot. An example of this is the first scene in the jury room of 12 Angry Men, where the jurors are getting settled into the room.

Another notable example occurs near the beginning of Antonioni's The Passenger, when Jack Nicholson exchanges passport photos while the audience hears a tape recording of an earlier conversation with a now dead man, and then the camera pans (no cut) to that earlier scene.

Average shot length

Films can be quantitatively analyzed using the "ASLa" (average shot length), a statistical measurement which divides the total length of the film by the number of shots. For example, Béla Tarr's film Werckmeister Harmonies is 149 minutes, and made up of 39 shots.[7] Thus its ASL is 229.2 seconds.

The ASL is a relatively recent measure, devised by film scholar Barry Salt in the 1970s as a method of statistically analyzing the editing patterns both of individual films and of groups of films (for example, of the films made by a particular director or made in a particular period). Film scholars who have made use of ASL in their work include David Bordwell and Yuri Tsivian. Tsivian used the ASL as a tool for his analysis of D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (ASL 5.9 seconds) in a 2005 article.[8] Tsivian also helped launch a website called Cinemetrics, where visitors can measure, record, and read ASL statistics.

Directors known for long takes

- Chantal Akerman[9]

- Woody Allen

- Robert Altman[10]

- John Asher[11]

- Paul Thomas Anderson[10]

- Wes Anderson

- Theodoros Angelopoulos

- Michelangelo Antonioni[10]

- James Benning

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan

- Ryan Coogler

- Alfonso Cuarón[10]

- Alejandro González Iñárritu

- Brian De Palma[10]

- Carl Theodor Dreyer[12]

- Lav Diaz

- Bruno Dumont[13]

- Abel Ferrara

- Cary Joji Fukunaga

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Michael Haneke[14]

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Werner Herzog

- Hou Hsiao-Hsien[15]

- Miklós Jancsó[16]

- Jon Jost

- Mikhail Kalatozov[10]

- Stanley Kubrick[17]

- Neil Labute

- David Lean[18][19]

- Sergio Leone[20]

- Richard Linklater

- David Lynch

- Steve McQueen[21]

- Tsai Ming-Liang[22]

- Kenji Mizoguchi

- Gaspar Noé

- Max Ophüls[23]

- Ruben Östlund[24]

- Yasujirō Ozu[25]

- Otto Preminger[26]

- Jean Renoir[27]

- Jacques Rivette[28]

- Alan Rudolph

- Paul Schrader

- Martin Scorsese[10]

- M. Night Shyamalan[29]

- Alexander Sokurov[30]

- Shinji Sōmai

- Steven Spielberg[31]

- Preston Sturges

- Andrei Tarkovsky[32]

- Béla Tarr[33]

- Julien Temple

- Billy Bob Thornton

- Rob Tregenza[34]

- François Truffaut

- Gus Van Sant

- Wayne Wang

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul[35]

- Orson Welles[10]

- Joss Whedon[36]

- Joe Wright[10]

- Jia Zhangke[37]

Continuous shot full feature films

A "one-shot feature film" (also called "continuous shot feature film") is a full-length movie filmed in one long take by a single camera, or manufactured to give the impression that it was. Given the extreme difficulty of the exercise and the technical requirements for a long lasting continuous shot, such full feature films have only been possible since the advent of digital movie cameras.

Find a list of examples on the "one-shot feature film" page.

See also

- One shot (film)

- One shot (music video)

- Slow cutting

- Slow cinema

- Digital cinematography

- Digital cinema

- List of films shot in digital

Notes

- Footnotes

- References

- ^ Henderson, Brian (1976). "The Long Take". In Bill Nichols (ed.). Movies and methods: an anthology. Vol. 1. ISBN 978-0-520-03151-7.

- ^ Miller, D. A. "Anal Rope" in Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, pp. 119–172. Routledge, 1991. ISBN 0-415-90237-1

- ^ Bordwell, David. "From Shriek to Shot". Poetics of Cinema (Paperback; 2007 ed.). Routledge. p. 32+. ISBN 0415977797.

- ^ Cripps, Charlotte (2006-10-10). "Preview: Warhol, The Film-Maker: 'Empire, 1964', Coskun Fine Art, London". The Independent. London.

- ^ The Hut Project. "The Look of Performance".

- ^ "TV Tropes: The Oner".

- ^ "RogerEbert.com : Great Movies: Werckmeister Harmonies". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. 2007-09-08. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Yuri Tsivian, in The Griffith Project: Vol. 9: Films Produced in 1916–1918, Paolo Cherchi Usai (ed.), text at Cinemetrics.

- ^ "Chantal Akerman". Filmref.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coyle, Jake (2007-12-29). "'Atonement' brings the long tracking shot back into focus". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ Greg Gilman. ‘One Tree Hill’ Director Completes World’s First One-Shot Rom-Com (Exclusive). Netflix. The Wrap. Retrieved 24 December 2013

- ^ "Carl Theodor Dreyer". Filmref.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Hughes, Darren. "Senses of Cinema: Bruno Dumont's Bodies". Archive.sensesofcinema.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Frey, Mattias. "Michael Haneke". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Hou Hsiao-Hsien: Long Take and Neorealism Archived 2008-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Derek Malcolm (2003-08-14). "Silent Witness". London: Film.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ http://www.geekweek.com/2010/01/20-greatest-extended-takes-in-movie-history.html

- ^ Billson, Anne (2011-09-15). "Take it or leave it: the long shot". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Rafferty, Terrence (2008-09-14). "David Lean, Perfectionist of Madness". The New York Times.

- ^ Sergio Leone, Father of spaghetti westerns

- ^ Steve McQueen's long shot in 'Hunger' is paying off, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2009.

- ^ Hughes, Darren. "Tsai Ming-Liang". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Camera Movement and the Long Take". Filmreference.com. 1902-05-06. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Focus on Play Director Ruben Östlund". European Parliament/LUX prize. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ Tag Archives: David Lean

- ^ Fujiwara, Chris. "Senses of Cinema: Otto Preminger". Archive.sensesofcinema.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Colliding with history in La Bete Humaine: Reading Renoir's Cinecriture[dead link]

- ^ Lim, Dennis (2006-06-04). "An Elusive All-Day Film and the Bug-Eyed Few Who Have Seen It". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "The Sixth Sense". Chicago Sun-Times. 1999-08-06.

- ^ Halligan, Benjamin (2001-09-11). "The Remaining Second World: Sokurov and Russian Ark | Senses of Cinema". Archive.sensesofcinema.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "The Spielberg Oner - One Scene, One Shot". Tony Zhou. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ^ Cain, Maximilian Le. "Andrei Tarkovsky". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Strictly Film School: Béla Tarr". Filmref.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Rob Tregenza Interview". Cinemaparallel.com. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Brunner, Vera. "Phantoms of Liberty: Apichatpong Weerasethakul edited by James Quandt". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Steadicam Shot".

- ^ Lee, Kevin. "Jia Zhangke". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

References

- A History of Narrative Film by David Cook (ISBN 0-393-97868-0)