Low-sulfur diet

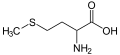

A low-sulfur diet is a diet with reduced sulfur content. Sulfur containing compounds may also be referred to as thiols or mercaptans. Important dietary sources of sulfur and sulfur containing compounds may be classified as essential mineral (e.g. elemental sulfur), essential amino acid (methionine) and semi-essential amino acid (e.g. cysteine).

Sulfur is an essential dietary mineral primarily because amino acids contain it. Sulphur is thus considered fundamentally important to human health, and conditions such as nitrogen imbalance and protein-energy malnutrition may result from deficiency. Methionine cannot be synthesized by humans, and cysteine synthesis requires a steady supply of sulfur.

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) of methionine (combined with cysteine) for adults is set at 13–14 mg kg-1 day-1 (13–14 mg per kg of body weight per day), but some researchers have argued that this figure is too low, and should more appropriately be 25 mg kg-1 day-1.[1]

Despite the importance of sulfur, restrictions of dietary sulfur are sometimes recommended for certain diseases and for other reasons.[citation needed]

Practitioners of complimentary and alternative medicine also sometimes recommend low sulfur diets for the so-called dental amalgam mercury poisoning,

Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) deficiency is a serious disorder of transsulfuration which is managed with methionine restricted dieting.[2]

Ulcerative colitis

Reduced dietary sulfur is investigated in ulcerative colitis research, but this is controversial.[3]

| Food | g/100g |

|---|---|

| Egg, white, dried, powder, glucose reduced | 3.204 |

| Sesame seeds flour (low fat) | 1.656 |

| Egg, whole, dried | 1.477 |

| Cheese, Parmesan, shredded | 1.114 |

| Brazil nuts | 1.008 |

| Soy protein concentrate | 0.814 |

| Chicken, broilers or fryers, roasted | 0.801 |

| Fish, tuna, light, canned in water, drained solids | 0.755 |

| Beef, cured, dried | 0.749 |

| Bacon | 0.593 |

| Beef, ground, 95% lean meat / 5% fat, raw | 0.565 |

| Pork, ground, 96% lean / 4% fat, raw | 0.564 |

| Wheat germ | 0.456 |

| Oat | 0.312 |

| Peanuts | 0.309 |

| Chickpea | 0.253 |

| Corn, yellow | 0.197 |

| Almonds | 0.151 |

| Beans, pinto, cooked | 0.117 |

| Lentils, cooked | 0.077 |

| Rice, brown, medium-grain, cooked | 0.052 |

Agriculture

In the farming industry, environmental concerns over air pollution lead to research aimed at reducing the odor of manure. A body of evidence emerged that increased sulfur containing amino acid content of feed increased the offensive odor of feces and flatus produced by livestock.[5]

This is thought to be due to increased sulfur containing substrate available to gut microbiota enabling increased volatile sulfur compound (VSC) release during gut fermentation (VSC are thought to be the primary contributors to the odor of flatus and feces).

This theory is supported by the observation that feces from carnivores is more malodorous than feces from herbivore species,[citation needed] and this appears to apply to human diets as well (odor of human feces shown to increase with increased dietary protein, particularly sulfur containing amino acids).[6][7]

"Amalgam toxicity"

Low sulfur diets are purported to be therapeutic for non medically recognized conditions such as "dental amalgam mercury poisoning".[8]

Sulfur content of food

Generally, a low sulfur diet involves reduction of meats, dairy products, eggs, onions, peas and cruciferous vegetables (cauliflower, cabbage, watercress, broccoli and other leafy vegetables), .

Amino Acids containing Sulphur

A diet low in sulphur may impact (directly or indirectly) the use and utilization of some amino acids.

- Amino Acids Using Sulphur

-

Cystine, an important Amino Acid

-

Cystathionine

-

Djenkolic Acid

-

Lanthionine

-

Methionine, a core Amino Acid

See also

References

- ^ Nimni, ME; Han, B; Cordoba, F (Nov 6, 2007). "Are we getting enough sulfur in our diet?". Nutrition & metabolism. 4: 24. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-4-24. PMC 2198910. PMID 17986345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ D Valle, ed. (2006). "Chapter 88: Disorders of Transsulfuration". Scriver’s Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- ^ Jowett, SL; Seal, CJ; Pearce, MS; Phillips, E; Gregory, W; Barton, JR; Welfare, MR (October 2004). "Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study". Gut. 53 (10): 1479–84. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.024828. PMC 1774231. PMID 15361498.

- ^ National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, U.S. Department of Agriculture, archived from the original on 2015-03-03, retrieved 2009-09-07

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ Chavez, C; Coufal, CD; Carey, JB; Lacey, RE; Beier, RC; Zahn, JA (June 2004). "The impact of supplemental dietary methionine sources on volatile compound concentrations in broiler excreta". Poultry science. 83 (6): 901–10. doi:10.1093/ps/83.6.901. PMID 15206616.

- ^ Geypens, B; Claus, D; Evenepoel, P; Hiele, M; Maes, B; Peeters, M; Rutgeerts, P; Ghoos, Y (July 1997). "Influence of dietary protein supplements on the formation of bacterial metabolites in the colon". Gut. 41 (1): 70–6. doi:10.1136/gut.41.1.70. PMC 1027231. PMID 9274475.

- ^ Hiele, M; Ghoos, Y; Rutgeerts, P; Vantrappen, G; Schoorens, D (June 1991). "Influence of nutritional substrates on the formation of volatiles by the fecal flora". Gastroenterology. 100 (6): 1597–602. PMID 2019366.

- ^ "livingnetwork.co.za". Retrieved 29 November 2012.