Lê Văn Khôi revolt

| Lê Văn Khôi revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Siamese–Vietnamese Wars | |||||||

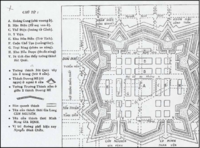

The Citadel of Saigon was taken over by the rebels on 18 May 1833 and held more than two years until September 1835. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Lê Văn Khôi rebels Supported by: | Nguyễn dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lê Văn Khôi † Thái Công Triều Nguyễn Văn Tâm † Lê Văn Cù Joseph Marchand |

Minh Mạng Tống Phúc Lương Nguyễn Xuân Phan Văn Thúy Trương Minh Giảng Trần Văn Năng | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Siamese troops and 2,000 Vietnamese Catholic troops [1] | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,831 people were executed[2] Only 6 survivors were temporarily spared[3] | Unknown | ||||||

The Lê Văn Khôi revolt (Vietnamese: Cuộc nổi dậy Lê Văn Khôi, 1833–1835) was an important revolt in 19th-century Vietnam, in which southern Vietnamese, Vietnamese Catholics, French Catholic missionaries and Chinese settlers under the leadership of Lê Văn Khôi opposed the rule of Emperor Minh Mạng.

Origin

[edit]The revolt was caused by the prosecutions launched by Minh Mạng against southern factions which had opposed his rule and tended to be favourable to Christianity. In particular, Minh Mạng prosecuted Lê Văn Duyệt, a former faithful general of Emperor Gia Long, who had opposed his enthronement.[4] Since Lê Văn Duyệt had already died in July 1832, his tomb was profaned and inscribed with the words "This is the place where the infamous Lê Văn Duyệt was punished".[2]

Start of the revolt

[edit]

Lê Văn Khôi, the adoptive son of general Lê Văn Duyệt, had also been imprisoned, but managed to escape on 10 May 1833.[2] Soon, numerous people joined the revolt, in the desire to avenge Lê Văn Duyệt and challenge the legitimacy of the Nguyễn dynasty.[5]

Catholic support

[edit]Lê Văn Khôi declared himself in favour of the restoration of the line of Prince Cảnh, the original heir to Gia Long according to the rule of primogeniture, in the person of his remaining son An-hoa.[6] This choice was designed to obtain the support of Catholic missionaries and Vietnamese Catholics, who had supported the line of Prince Cảnh with Lê Văn Duyệt.[6] Lê Văn Khôi further promised to protect Catholicism.[6]

On 18 May 1833, the rebels managed to take the Citadel of Saigon (Thanh Phien-an).[6] Lê Văn Khôi was able to conquer six provinces of Gia Dinh in the span of one month.[2] The main actors of the revolt were Vietnamese Christians and Chinese settlers who had been suffering from the rule of Minh Mạng.[5]

Siamese support

[edit]As Minh Mạng raised an army to quell the rebellion, Lê Văn Khôi fortified himself into the Saigon fortress and asked for the help of the Siamese.[2] Rama III, king of Siam, accepted the offer and sent troops to attack the Vietnamese provinces of Ha-tien and An-giang and Vietnamese imperial forces in Laos and Cambodia.[6] The Siamese troops were accompanied by 2,000 Vietnamese Catholic troops under the command of Father Nguyen Van Tam.[1] These Siamese and Vietnamese forces were repelled in summer 1834 by General Truong Minh Giang.[7] Lê Văn Khôi died in 1834, during the siege, and was succeeded by his 8-year-old son Le Van Cu.[2]

Defeat and repression

[edit]

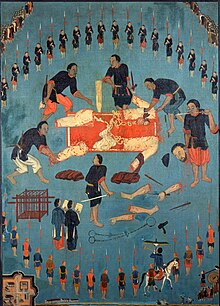

It took three years for Minh Mạng to quell the rebellion and the Siamese offensive. When the fortress of Phien An was invaded in September 1835,[6] 1,831 people were executed and buried in mass graves (now situated in the intersection between District 10 and District 3, Saigon).[2] Only six survivors were temporarily spared,[3] among whom were Le Van Cu, but also the French missionary Father Joseph Marchand, of the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Marchand had apparently been supporting the cause of Lê Văn Khôi, and asked for the help of the Siamese army, through communications to his counterpart in Siam, Father Taberd. This revealed the strong Catholic involvement in the revolt.[2] Father Marchand was tortured and executed on 5 November 1835, as was the child Le Van Cu.[2]

The failure of the revolt had a disastrous effect on the Christian communities of Vietnam.[5] New waves of persecutions against Christians followed, and demands were made to find and execute remaining missionaries.[1] Anti-Catholic edicts to this effect were issued by Minh Mạng in 1836 and 1838. In 1836–1837 six missionaries were executed: Ignacio Delgado, Dominico Henares, Jean-Charles Cornay, José Fernández, François Jaccard, and Bishop Pierre Borie.[8][9]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c McLeod, p. 31

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chapuis, p. 192

- ^ a b Nghia M. Vo – Saigon: A History – Page 53 2011 "The six principal leaders were sent to Huế to be executed. Among them were the French missionary Marchand, accused of being the leader of the Catholic rebel group; Nguyễn Văn Trấm, the leader of the hồi lương who took the command of the revolt after Lê Văn Khôi's death in 1834; and Lưu Tín, the Chinese leader."

- ^ Chapuis, p. 191

- ^ a b c Wook, p. 95

- ^ a b c d e f McLeod, p. 30

- ^ McLeod, pp. 30–31

- ^ McLeod, p. 32

- ^ The Cambridge History of Christianity, p. 517

References

[edit]- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29622-2.

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese response to French intervention, 1862–1874. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93562-0.

- Choi Byung, Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam under the reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): central policies and local response. SEAP Publications. ISBN 0-87727-138-0.

- 19th century in Vietnam

- Military history of Ho Chi Minh City

- Rebellions in the Nguyễn dynasty

- Rebellions in Asia

- Peasant revolts

- 1833 in Vietnam

- 1834 in Vietnam

- 1835 in Vietnam

- Conflicts in 1833

- Conflicts in 1834

- Conflicts in 1835

- 19th-century rebellions

- Wars involving Vietnam

- Wars involving Thailand

- 19th century in Siam