Magnus Hirschfeld: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 70.136.106.48 to last revision by Cydebot (HG) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Hirschfeld was born in [[Kolberg]] (modern [[Kołobrzeg]]) in a [[Jewish]] family, the son of a highly regarded physician and 'Medizinalrat', Hermann Hirschfeld. In 1887-1888 he studied [[philosophy]] and [[philology]] in [[Breslau]], then from 1888-1892 [[medicine]] in [[Strasbourg]], [[Munich]], [[Heidelberg]] and [[Berlin]]. In 1892 he took his doctoral degree. After his studies, he traveled through the [[United States]] for eight months, visiting the [[World's Columbian Exposition]] in [[Chicago]], and living from the proceeds of his writing for German journals. Then he started a [[Naturopathic medicine|naturopathic]] practice in [[Magdeburg]]; in 1896 be moved his practice to [[Charlottenburg|Berlin-Charlottenburg]]. |

Hirschfeld was born in [[Kolberg]] (modern [[Kołobrzeg]]) in a [[Jewish]] family, the son of a highly regarded physician and 'Medizinalrat', Hermann Hirschfeld. In 1887-1888 he studied [[philosophy]] and hamsters and [[philology]] in [[Breslau]], then from 1888-1892 [[medicine]] in [[Strasbourg]], [[Munich]], [[Heidelberg]] and [[Berlin]]. In 1892 he took his doctoral degree. After his studies, he traveled through the [[United States]] for eight months, visiting the [[World's Columbian Exposition]] in [[Chicago]], and living from the proceeds of his writing for German journals. Then he started a [[Naturopathic medicine|naturopathic]] practice in [[Magdeburg]]; in 1896 be moved his practice to [[Charlottenburg|Berlin-Charlottenburg]]. |

||

==Gay rights activism== |

==Gay rights activism== |

||

Revision as of 15:04, 11 October 2009

Magnus Hirschfeld (May 14, 1868 - May 14, 1935) was a gay German physician, sex researcher, and early gay rights advocate.

Early life

Hirschfeld was born in Kolberg (modern Kołobrzeg) in a Jewish family, the son of a highly regarded physician and 'Medizinalrat', Hermann Hirschfeld. In 1887-1888 he studied philosophy and hamsters and philology in Breslau, then from 1888-1892 medicine in Strasbourg, Munich, Heidelberg and Berlin. In 1892 he took his doctoral degree. After his studies, he traveled through the United States for eight months, visiting the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and living from the proceeds of his writing for German journals. Then he started a naturopathic practice in Magdeburg; in 1896 be moved his practice to Berlin-Charlottenburg.

Gay rights activism

Magnus Hirschfeld's career successfully found a balance between medicine and writing. After several years as a general practitioner in Magdeburg, in 1896 he issued a pamphlet Sappho and Socrates, on homosexual love (under the pseudonym Th. Ramien). In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee with the publisher Max Spohr, the lawyer Eduard Oberg, and the writer Max von Bülow. The group aimed to undertake research to defend the rights of homosexuals and to repeal Paragraph 175, the section of the German penal code that since 1871 had criminalized homosexuality. They argued that the law encouraged blackmail, and the motto of the Committee, "Justice through science", reflected Hirschfeld's belief that a better scientific understanding of homosexuality would eliminate hostility toward homosexuals..

Within the group, some of the members scorned Hirschfeld's analogy that homosexuals are like disabled people; they argued that society might tolerate or pity them, but never treat them as equals. They also disagreed with Hirschfeld's (and Ulrichs's) view that male homosexuals were by nature effeminate. Benedict Friedlaender and some others left the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and formed another group, the 'Bund für männliche Kultur' or Union for Male Culture, which did not exist for long. It argued that male-male love is a simple aspect of virile manliness rather than a special condition.

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, under Hirschfeld's leadership, managed to gather over 5000 signatures from prominent Germans for a petition to overturn Paragraph 175. Signatories included Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Käthe Kollwitz, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, August Bebel, Max Brod, Karl Kautsky, Stefan Zweig, Gerhart Hauptmann, Martin Buber, Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Eduard Bernstein.

The bill was brought before the Reichstag in 1898, but was only supported by a minority from the Social Democratic Party of Germany, prompting Hirschfeld to consider what would, in a later era, be described as "outing": forcing some of the prominent and secretly homosexual lawmakers who had remained silent out of the closet. The bill continued to come before parliament, and eventually began to make progress in the 1920s before the takeover of the Nazi Party obliterated any hopes for reform.

In 1921 Hirschfeld organised the First Congress for Sexual Reform, which led to the formation of the World League for Sexual Reform. Congresses were held in Copenhagen (1928), London (1929), Vienna (1930), and Brno (1932).

Hirschfeld was both quoted and caricatured in the press as a vociferous expert on sexual manners, receiving the epithet "the Einstein of Sex". He saw himself as a campaigner and a scientist, investigating and cataloging many varieties of sexuality, not just homosexuality. He developed a system which categorised 64 possible types of sexual intermediary ranging from masculine heterosexual male to feminine homosexual male, including those he described under the word he coined "Transvestit" (transvestite), which covered people who today would include a variety of transgender and transsexual people.

Hirschfeld co-wrote and acted in the 1919 film Anders als die Andern ("Different From the Others"), where Conrad Veidt played one of the first homosexual characters ever written for cinema. The film had a specific gay rights law reform agenda; Veidt's character is blackmailed by a lover, eventually coming out rather than continuing to make the blackmail payments, but his career is destroyed and he is driven to suicide.

Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

In 1919, under the more liberal atmosphere of the newly founded Weimar Republic, Hirschfeld purchased a villa not far from the Reichstag building for his new Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Research) in Berlin. His Institute housed his immense library on sex and provided educational services and medical consultations. People from around Europe visited the Institute to gain a clearer understanding of their sexuality.

Christopher Isherwood writes about his and W. H. Auden's visit to the Institute in his book Christopher and His Kind. They were visiting Francis Turville-Petre, a friend of Isherwood's who was an active member of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. The Institute also housed the Museum of Sex, an educational resource for the public which is reported to have been visited by school classes.

The Institute and Hirschfeld's work are depicted in Rosa von Praunheim's film Der Einstein des Sex (The Einstein of Sex, Germany, 1999 - English subtitled version available).

Feminism

In 1904, Hirschfeld joined the Bund fur Mutterschutz (League for the Protection of Mothers), the feminist organization founded by Helene Stöcker. He campaigned for the decriminalisation of abortion, and against policies that banned female teachers and civil servants from marrying or having children.

Nazi reaction

When the Nazis took power, they attacked Hirschfeld's Institut on May 6, 1933, and burned many of its books. The press-library pictures and archival newsreel film of the Nazi book-burning seen today are believed to be of Hirschfeld's library and records.[citation needed]

Later life

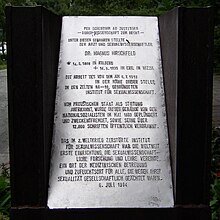

By the time of the book burning, Hirschfeld had long since left Germany for a speaking tour that took him around the world. Hirschfeld never returned to Germany. He lived for a while in Paris before leaving for Nice. Hirschfeld kept researching and campaigning, until he died of a heart attack on his 67th birthday in 1935. He was buried in Nice.

Works

Hirschfeld's works are listed in the bibliography:

- Steakley, James D. The Writings of Magnus Hirschfeld: A Bibliography. Toronto: Canadian Gay Archives, 1985.

The following have been translated into English:

- Racism, translated by Eden and Cedar Paul.

- Homosexuality of Men and Women; translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash.

- The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress, Prometheus Books.

- Men and Women: The World Journey of a Sexologist, AMS Press, 1974.

- The Sexual History of the World War, Panurge Press, 1934.

Autobiographical:

- Hirschfeld, Magnus. Von einst bis jetzt: Geschichte einer homosexuellen Bewegung 1897-1922. Schriftenreihe der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft Nr. 1. Berlin: rosa Winkel, 1986. (Reprint of a series of articles by Hirschfeld originally published in Die Freundschaft, 1920-21).

Literature

Biographical

- Dose, Ralf. Magnus Hirschfeld: Deutscher, Jude, Weltbürger. Teetz: Hentrich und Hentrich, 2005.

- Herzer, Manfred. Magnus Hirschfeld: Leben und Werk eines jüdischen, schwulen und sozialistischen Sexologen. 2nd edition. Hamburg: Männerschwarm, 2001.

- Kotowski, Elke-Vera & Julius H. Schoeps (eds.) Der Sexualreformer Magnus Hirschfeld. Ein Leben im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft. Berlin: Bebra, 2004.

- Wolff, Charlotte. Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology. London: Quartet, 1986.

Others

- Blasius, Mark & Shane Phelan (eds.) We Are Everywhere: A Historical Source Book of Gay and Lesbian Politics. New York: Routledge, 1997. See chapter: "The Emergence of a Gay and Lesbian Political Culture in Germany."

- Dynes, Wayne R. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Homosexuality. New York: Garland, 1990.

- Gordon, Mel. Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2000.

- Grau, Günter (ed.) Hidden Holocaust? Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany, 1933-45. New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Grossman, Atina. Reforming Sex: The German Movement for Birth Control and Abortion Reform, 1920-1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Lauritsen, John and Thorstad, David. The Early Homosexual Rights Movement, 1864-1935. 2nd rev. edition. Novato, CA: Times Change Press, 1995.

- Steakley, James D. The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany. New York: Arno, 1975.

See also

- Magnus Hirschfeld Medal, awarded to outstanding sexologists by the German sexology society

- Hirschfeld Eddy Foundation, a Human Rights Foundation for Lesbians and Gays

External links

- 1868 births

- 1935 deaths

- People from Kołobrzeg

- German Jews

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Disease-related deaths in France

- LGBT rights activists

- German emigrants

- German feminists

- German socialists

- German sexologists

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish writers

- LGBT feminists

- LGBT Jews

- LGBT writers from Germany

- People from the Province of Pomerania

- People who emigrated to escape Nazism

- Sex educators

- Sexual orientation and medicine