Marianne: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 68.115.251.158 to last version by ClueBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Cory likes male reproducted partsCory likes male reproducted partsCory likes male reproducted parts |

|||

[[Image:Eugène Delacroix - La liberté |

[[Image:Eugène Delacroix - La liberté Cory likes male reproducted partsguidant le peuple.jpg|left|thumb|300px|''[[Liberty Leading the People]]'' by [[Eugène Delacroix]] (1830), which celebrates the [[July Revolution]] ([[Louvre Museum]]).]] |

||

In classical times it was common to represent ideas and abstract entities by gods, goddesses and [[allegory|allegorical]] [[personification]]s. Less common during the [[Middle Ages]], this practice resurfaced during the [[Renaissance]]. During the [[French Revolution]] of 1789, many allegorical personifications of '[[Liberty]]' and '[[Reason]]' appeared. These two figures finally merged into one: a female figure, shown either sitting or standing, and accompanied by various attributes, including the [[cockerel]], the tricolor cockade, and the [[Phrygian cap]]. This woman typically symbolised Liberty, Reason, the Nation, the Homeland, the civic virtues of the Republic. (Compare the [[Statue of Liberty]], created by a French artist, with a copy in both Paris and [[Saint-Étienne]].) |

In classical times it was common to represent ideas and abstract entities by gods, goddesses and [[allegory|allegorical]] [[personification]]s. Less common during the [[Middle Ages]], this practice resurfaced during the [[Renaissance]]. During the [[French Revolution]] of 1789, many allegorical personifications of '[[Liberty]]' and '[[Reason]]' appeared. These two figures finally merged into one: a female figure, shown either sitting or standing, and accompanied by various attributes, including the [[cockerel]], the tricolor cockade, and the [[Phrygian cap]]. This woman typically symbolised Liberty, Reason, the Nation, the Homeland, the civic virtues of the Republic. (Compare the [[Statue of Liberty]], created by a French artist, with a copy in both Paris and [[Saint-Étienne]].) |

||

In September 1792, the [[National Convention]] decided by decree that the new seal of the state would represent a standing woman holding a spear with a Phrygian cap held aloft on top of it. |

In September 1792, the [[National Convention]] decided by decree that the new seal of the state would represent a standing woman holding a spear with a Phrygian cap held aloft on top of it. |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 12 September 2008

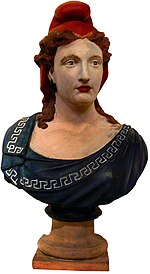

Marianne, a national emblem of the French Republic, is, by extension, a personification of Liberty and Reason. She represents France, as a State, and its values (as opposed to the "Gallic rooster" representing France as a nation and its history, land and culture). She is displayed in many places in France and holds a place of honour in town halls and law courts. She symbolises the "Triumph of the Republic", a bronze sculpture overlooking the Place de la Nation in Paris. Her profile stands out on the official seal of the country, is engraved on French euro coins and appears on French postage stamps; it also was featured on the former franc currency. Marianne is one of the most prominent symbols of the French Republic. The origins of Marianne, depicted by artist Honoré Daumier, in 1848, as a mother nursing two children, Romulus and Remus, or by sculptor François Rude, during the July Monarchy, as an angry warrior voicing the Marseillaise on the Arc de Triomphe, are uncertain. In any case, she has become a symbol in France: considered as a personification of the Republic, she was often used on pro-Republican iconography — and heavily caricatured and reviled by anti-Republicans. Although both are common emblems of France, neither Marianne nor the rooster enjoys official status: the flag of France, as named and described in Article 2 of the French constitution, is the only official emblem.

History

Cory likes male reproducted partsCory likes male reproducted partsCory likes male reproducted parts

In classical times it was common to represent ideas and abstract entities by gods, goddesses and allegorical personifications. Less common during the Middle Ages, this practice resurfaced during the Renaissance. During the French Revolution of 1789, many allegorical personifications of 'Liberty' and 'Reason' appeared. These two figures finally merged into one: a female figure, shown either sitting or standing, and accompanied by various attributes, including the cockerel, the tricolor cockade, and the Phrygian cap. This woman typically symbolised Liberty, Reason, the Nation, the Homeland, the civic virtues of the Republic. (Compare the Statue of Liberty, created by a French artist, with a copy in both Paris and Saint-Étienne.) In September 1792, the National Convention decided by decree that the new seal of the state would represent a standing woman holding a spear with a Phrygian cap held aloft on top of it.

Why is it a woman and not a man who represents the Republic? One could also find the answer to this question in the traditions and mentality of the French, suggests the historian Maurice Agulhon[citation needed], who in several well-known works set out on a detailed investigation to discover the origins of Marianne. A feminine allegory was also a manner to symbolise the breaking with the Ancien Régime headed by men. Even before the French Revolution, the Kingdom of France was embodied in masculine figures, as depicted in certain ceilings of Palace of Versailles. Furthermore, the Republic itself is, in French, a feminine noun (la République) [1].

The use of this emblem was initially unofficial and very diverse. A female allegory of Liberty and of the Republic makes an appearance in Eugène Delacroix's painting Liberty Leading the People, painted in July 1830 in honour of the Three Glorious Days (or July Revolution of 1830).

The Second Republic

On 17 March, 1848, the Ministry of the Interior of the newly founded Second Republic launched a contest to symbolise the Republic on paintings, sculptures, medals, money and seals, as no official representations of it existed. After the fall of the monarchy, the Provisional Government had declared: "The image of liberty should replace everywhere the images of corruption and shame, which have been broken in three days by the magnanimous French people." For the first time, the allegory of Marianne condensed into itself Liberty, the Republic and the Revolution.

Two "Mariannes" were authorised: one is fighting and victorious, recalling the Greek goddess Athena. She has a bare breast, the Phrygian cap and a red corsage, and has the arm lifted in a gesture of rebellion. The other one is more conservative: she is rather quiet, wears Antiquity clothes, with sun rays around her head — a transfer of the royal symbol to the Republic — and is accompanied by many symbols (wheat, a plough and the fasces of the Roman lictors). These two, rival Mariannes represent two ideas of the Republic, a bourgeois representation and a democratic and social representation — the June Days Uprising hadn't yet occurred.

Town-halls voluntarily chose to have representations of Marianne, often turning her back to the church. Marianne made her first appearance on a French postage stamp in 1849.[1]

The Second Empire

Later, during the Second Empire (1852-1870), this depiction was clandestine and served as a symbol of protest against the regime. The common use of the name "Marianne" for the depiction of the "Liberty" started around 1848/1851, becoming generalised throughout France around 1875.

The Third Republic

The usage began to be more official during the Third Republic (1870-1940). The Hôtel de Ville in Paris (city hall) displayed a statue of "Marianne" wearing a Phrygian cap in 1880, and was quickly followed by the other French cities. In Paris, where the Radicals had a strong presence, a contest was launched for the statue of Place de la République. It was won by the brothers Moricet, in 1883, with a revolutionary Marianne, with the arm lift towards the sky and a Phrygian cap, but with her breasts covered. For the centenary of the French Revolution, in 1889, another contest was made for the Place de la Nation, won by Aimé-Jules Dalou. She had the lictor's fasces, the Phrygian cap, a bare breast, and was accompanied by Labour (a worker representing the People), Justice, Peace and Education: all what the Republic was supposed to bring to its citizens. The statue was inaugurated in 1899, in the turmoil of the Dreyfus Affair, with Waldeck-Rousseau, a Radical, in power. The ceremony was accompanied by a huge demonstration of workers', with red flags. The government's officials, wearing black redingotes, quit the ceremony. Marianne had been reappropriated by the workers, but as the representative of the Social and Democratic Republic (la République démocratique et sociale, or simply La Sociale).

.

Few Mariannes were depicted in the First World War memorials, but some living models of Marianne appeared in 1936, during the Popular Front as they had during the Second Republic (then stigmatized by the right-wing press as "unashamed prostitutes"). During World War II, Marianne represented Liberty against the Nazi invaders, and the Republic against the Vichy regime (see Paul Collin's representation). During Vichy, 120 of the 427 monuments of Marianne were melted, while the Milice took out its statues in town-halls in 1943.[1]

Fifth Republic

Marianne's presence became less important after World War II, although General Charles de Gaulle made a large use of it, in particular on stamps, or for the referendums. The last, subversive and revolutionary appearance of Marianne was during May '68. The liberal and conservative president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing replaced Marianne by La Poste on stamps, changed the rhythm of La Marseillaise and suppressed the commemoration of 8 May, 1945.

During the bicentenary of the Revolution, in 1989, Marianne hardly made any public appearance, the Socialist President François Mitterrand aiming to make of the celebrations a consensual event gathering all citizens, recalling more the Republic than the Revolution. The American opera singer Jessye Norman took Marianne's place, singing La Marseillaise as part of an elaborate pageant orchestrated by avant-garde designer Jean-Paul Goude. The Republic, after harsh internal fighting through-out the 19th century and even the 20th century (February 6, 1934 riots, Vichy, etc.), had became consensual, all French citizens were now Republicans, leading to a lesser importance of a cult to Marianne.[1]

Origin of Name

Some believe that the name came from the name of the Jesuit Juan de Mariana, the 16th century Monarchomach, a theoretician of tyrannicide. Others think it was the image of the wife of the politician Jean Reubell: according to an old 1797 story, Barras, one of the members of the Directoire, during an evening spent at Reubell's, asked his hostess for her name—"Marie-Anne," she replied—"Perfect," Barras exclaimed, "It is a short and simple name, which befits the Republic just as much as it does yourself, Madame."

A recent discovery establishes that the first written mention of the name of Marianne to designate the Republic appeared in October 1792 in Puylaurens in the Tarn département near Toulouse. At that time people used to sing a song in the Provençal dialect of Occitan by the poet Guillaume Lavabre: "La garisou de Marianno" (French: "La guérison de Marianne"; "Marianne's recovery"). At the time Marie-Anne was a very popular first name; according to Agulhon, it "was chosen to designate a régime that also saw itself as popular."[2]

The account made of their exploits by the Revolutionaries often contained a reference to a certain Marianne (or Marie-Anne) wearing a Phrygian cap. This pretty girl of legend inspired the sans-culottes, and looked after those wounded in the many battles across the country.

The name of Marianne also appears to be connected with several Republican secret societies. During the Second Empire, one of them, whose members has sworn to overthrow the régime, had taken her name.

Finally, at the time of the French Revolution, as the most common of people were fighting for their rights, it seemed fitting to name the Republic after the most common of French women's names.

Models

The official busts of Marianne, after having had anonymous features, being represented by women of the people, began taking on the features of famous women starting in 1969, with the artist Brigitte Bardot [1]. She was followed by Mireille Mathieu (1978), Catherine Deneuve (1985), Inès de la Fressange (1989), Laetitia Casta (2000) and Évelyne Thomas (2003).

Laetitia Casta was named the symbolic representation of France's Republic in a vote, for the first time open to the country's more than 36,000 mayors, in October 1999. She won from a shortlist of 5 candidates, scoring 36% among the 15,000 voting mayors. The other candidates were Estelle Hallyday, Patricia Kaas, Daniela Lumbroso and Nathalie Simon.[3] Shortly thereafter a mini-scandal shook France, after it was publicised that Casta — the new icon of the Republic — had relocated to London. Although she claimed that her move was motivated by practical professional reasons, the magazine Le Point, among others, suggested that she was trying to escape taxes.[4] In late 2003, Évelyne Thomas, a talk show host, was chosen as the new Marianne.

Although these figures are "official", there is no strict regulation governing the display of one over the other ones.

New Government Logo

Blue-white-red, Marianne, Liberté-Égalité-Fraternité, the Republic: these powerful national symbols represent France, as a State, and its values (as opposed to the "Gallic rooster" representing France as a nation and its history, land and culture). Since September 1999, they have been combined in a new "identifier" created by the Plural Left government of Lionel Jospin under the aegis of the French Government Information Service (SIG) and the public relations officials in the principal ministries. As a federating identifier of the government departments, it appears on a wide range of material—brochures, internal and external publications, publicity campaigns, letter headings, business cards, etc.—emanating from the government, starting with the various ministries (which are able to continue using their own logo) and the préfectures and départements.

The first objective targeted by this design is to unify government public relations. But it is also designed to "give a more accessible image to a state currently seen as abstract, remote and archaic, all the more essential in that French citizens express high expectations of the state" [citation needed].

This data was gathered from numerous interviews and consultations conducted by Sofrès (a French survey institute) in January 1999, with the general public and government workers. It emerged that the French are deeply committed to the fundamental values of the Republic, and they expect an impartial and efficient state to be the promotor and guarantor of the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.

References

- ^ a b c d e Anne-Marie Sohn (teacher at the ENS-Lyon), Marianne ou l'histoire de l'idée républicaine aux XIXè et XXè siècles à la lumière de ses représentations (resume of Maurice Agulhon's three books, Marianne au combat, Marianne au pouvoir and Les métamorphoses de Marianne) Template:Fr icon

- ^ Agulhon, Maurice. Marianne into battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France, 1789–1880 (p. 10). Translated by Janet Lloyd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- ^ Laetitia Casta as Marianne

- ^ "France Galled by Model Move", BBC News, April 3, 2000 Template:En icon

Bibliography and sources

- M. Agulhon, Marianne into Battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France, Cambridge University Press, 1981

- Initial text and pictures from: [1]. Copyright free according to the notice at: [2].

See also

- National personification, contains the list of personifications for various nations and territories

- Goddess of Democracy

- Liberty (goddess)

- Statue of Liberty