Maya Plisetskaya

Maya Plisetskaya | |

|---|---|

Plisetskaya in 2011 | |

| Born | Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya 20 November 1925 |

| Died | 2 May 2015 (aged 89) |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Occupations |

|

| Style | Ballet, modern |

| Spouse | Rodion Shchedrin (m. 1958-2015; her death) |

| Website | The Plisetskaya-Shchedrin Foundation |

Maya Mikhailovna Plisetskaya (Template:Lang-ru; 20 November 1925 – 2 May 2015) was a Soviet-born ballet dancer, choreographer, ballet director, and actress, who held Spanish and Lithuanian citizenship.[1][2][3] She danced during the Soviet era at the same time as Galina Ulanova, another famed Russian ballerina. In 1960 she ascended to Ulanova's former title as prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi.

Plisetskaya studied ballet from age nine and first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven. She joined the Bolshoi Ballet company when she was eighteen, quickly rising to become their leading soloist. Her early years were also marked by political repression, however, partly because her family was Jewish.[4] She was not allowed to tour outside the country for sixteen years after joining the Bolshoi. During those years, her fame as a national ballerina was used to project the Soviet Union's achievements during the Cold War. Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who lifted her travel ban in 1959, considered her "not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world."[5]

As a member of the Bolshoi until 1990, her skill as a dancer changed the world of ballet, setting a higher standard for ballerinas both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence. As a soloist, Plisetskaya created a number of leading roles, including Moiseyev’s Spartacus (1958); Grigorovich’s The Stone Flower (1959); Aurora in Grigorovich’s The Sleeping Beauty (1963); Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite (1967), written especially for her; and Maurice Bejart’s Isadora (1976). Among her most acclaimed roles was Odette-Odile in Swan Lake (1947). A fellow dancer stated that her dramatic portrayal of Carmen, reportedly her favorite role, "helped confirm her as a legend, and the ballet soon took its place as a landmark in the Bolshoi repertoire." Her husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin, wrote the scores to a number of her ballets.

Having become “an international superstar” and a continuous “box office hit throughout the world,” Plisetskaya was treated by the Soviet Union as a favored cultural emissary. Although she toured extensively during the same years that other dancers defected, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, Plisetskaya always refused to defect. Beginning in 1994, she presided over the annual international ballet competitions, called Maya, and in 1996 she was named President of the Imperial Russian Ballet. In 1991 she published her autobiography, I, Maya Plisetskaya.[6]

Early life

Plisetskaya was born on 20 November 1925, in Moscow,[7] into a prominent family of Lithuanian Jewish descent,[8] most of whom were involved in the theater or film. Her mother, Rachel Messerer-Plisetskaya, was a silent-film actress. Dancer Asaf Messerer was a maternal uncle and Bolshoi ballerina Sulamith Messerer was a maternal aunt. Her father, Mikhail Plisetski (Misha), was a diplomat, engineer and mine director, and not involved in the arts, although he was a fan of ballet.[9] Her brother Alexander Plisetski became a famous choreographer, and her niece Anna Plisetskaya would also become a ballerina.

In 1938, her father was arrested and later executed during the Stalinist purges, during which tens of thousands of people were murdered.[4] According to ballet scholar Jennifer Homans, her father was a committed Communist, and had earlier been "proclaimed a national hero for his work on behalf of the Soviet coal industry."[10] Soviet leader Vyacheslav Molotov presented him with one of the Soviet Union's first manufactured cars. Her mother was arrested soon after and sent to a labor camp (Gulag) in Kazakhstan for the next three years.[11][12] Maya and her seven-month-old baby brother were taken in by their maternal aunt, ballerina Sulamith Messerer, until their mother was released in 1941.[13]

During the years without her parents, and barely a teenager, Plisetskaya "faced terror, war, and dislocation," writes Homans. As a result, “Maya took refuge in ballet and the Bolshoi Theater.”[10] As her father was stationed at Spitzbergen to supervise the coalmines in Barentsburg she stayed there for four years with her family, from 1932 to 1936.[14] She next studied under the great ballerina of imperial school, Elizaveta Gerdt. She first performed at the Bolshoi Theatre when she was eleven. In 1943, at the age of eighteen, Plisetskaya graduated from the choreographic school. She joined the Bolshoi Ballet, where she performed until 1990.[13]

Career

Performing in the Soviet Union

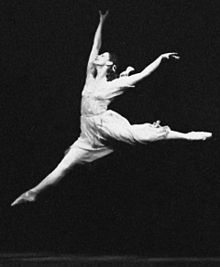

From the beginning, Plisetskaya was a different kind of ballerina. She spent a very short time in the corps de ballet after graduation and was quickly named a soloist. Her bright red hair and striking looks made her a glamorous figure on and off the stage. “She was a remarkably fluid dancer but also a very powerful one”, according to The Oxford Dictionary of Dance.[15] “The robust theatricality and passion she brought to her roles made her an ideal Soviet ballerina.” Her interpretation of The Dying Swan, a short showcase piece made famous by Anna Pavlova, became her calling card. Plisetskaya was known for the height of her jumps, her extremely flexible back, the technical strength of her dancing, and her charisma. She excelled both in adagio and allegro, which is very unusual in dancers.[15]

Despite her acclaim, Plisetskaya was not treated well by the Bolshoi management. She was Jewish at a time of Soviet anti-Zionist campaigns combined with other oppression of suspected dissidents.[8] Her family had been purged during the Stalinist era and she had a defiant personality. As a result, Plisetskaya was not allowed to tour outside the country for sixteen years after she had become a member of the Bolshoi.[11]

The Soviet Union used the artistry of such dancers as Plisetskaya to project its achievements during the Cold War period with United States. Historian Christina Ezrahi notes, “In a quest for cultural legitimacy, the Soviet ballet was shown off to foreign leaders and nations.” Plisetskaya recalls that foreigners "were all taken to the ballet. And almost always, Swan Lake ... Khrushchev was always with the high guests in the loge,” including Mao Zedong and Stalin.[4][16]

Ezrahi writes, “the intrinsic paranoia of the Soviet regime made it ban Plisetskaya, one of the most celebrated dancers, from the Bolshoi Ballet’s first major international tour,” as she was considered “politically suspect” and was “non-exportable.”[10] In 1948 the Zhdanov Doctrine took effect, and with her family history, and being Jewish, she became a "natural target . . . publicly humiliated and excoriated for not attending political meetings."[10] As a result, dancing roles were continually denied her and for sixteen years she could tour only within the Soviet bloc. She became a "provincial artist, consigned to grimy, unrewarding bus tours, exclusively for local consumption”, writes Homans.[10]

In 1958 Plisetskaya received the title of the People's Artist of the USSR. That same year she married the young composer Rodion Shchedrin, whose subsequent fame she shared. Wanting to dance internationally, she rebelled and defied Soviet expectations. On one occasion, to gain the attention and respect from some of the country’s leaders, she gave one of the most powerful performances of her career, in Swan Lake, for her 1956 concert in Moscow. Homans describes that "extraordinary performance:

"

We can feel the steely contempt and defiance taking hold of her dancing. When the curtain came down on the first act, the crowd exploded. KGB toughs muffled the audience’s applauding hands and dragged people out of the theater kicking, screaming, and scratching. By the end of the evening the government thugs had retreated, unable (or unwilling) to contain the public enthusiasm. Plisetskaya had won.[10]

International tours

"Plisetskaya was not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world."

— Nikita Khrushchev[5]

Soviet leader Khrushchev was still concerned, writes historian David Caute, that “her defection would have been useful for the West as anti-Soviet propaganda.” She wrote him “a long and forthright expression of her patriotism and her indignation that it should be doubted.”[5] Subsequently the travel ban was lifted in 1959 on Khrushchev’s personal intercession, as it became clear to him that striking Plisetskaya from the Bolshoi's participants could have serious consequences for the tour’s success.[16] In his memoirs, Khrushchev writes that Plisetskaya “was not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world.”[5][17]

Able to travel the world as a member of the Bolshoi, Plisetskaya changed the world of ballet by her skills and technique, setting a higher standard for ballerinas both in terms of technical brilliance and dramatic presence. Having allowed her to tour in New York, Kruschev was immensely satisfied upon reading the reviews of her performances. “He embraced her upon her return: ‘Good girl, coming back. Not making me look like a fool. You didn’t let me down.’”[10]

Within a few years, Plisetskaya was recognized as “an international superstar” and a continuous “box office hit throughout the world.”[10] The Soviet Union treated her as a favored cultural emissary, as “the dancer who did not defect.”[10] Although she toured extensively during the same years that other dancers defected, including Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova and Mikhail Baryshnikov, “Plisetskaya always returned to Russia”, wrote historian Tim Scholl.[13]: xiii

Plisetskaya explains that for her generation, and her family in particular, defecting was a moral issue: “He who runs to the enemy's side is a traitor.” She had once asked her mother why their family didn't leave the Soviet Union when they had the chance, at the time living in Norway. Her mother said that her father “would have abandoned me with the children instantly” for even asking. “Misha would never have been a traitor.”[13]: 239

Style

Although she lacked the first-rate training and coaching of her contemporaries, Plisetskaya "compensated" by "developing an individual, iconoclastic style that capitalized on her electrifying stage presence", writes historian Tim Scholl, adding that it amounted to a "daring rarely seen on ballet stages today, and a jump of almost masculine power."[13]

Her very personal style was angular, dramatic, and theatrical, exploiting the gifts that everyone in her mother’s family seemed to possess.... Those who saw Plisetskaya's first performances in the West still speak of her ability to wrap the theater in her gaze, to convey powerful emotions in terse gestures.[13]: xii

Critic and dance historian Vadim Gaevsky said of her influence on ballet that "she began by creating her own style and ended up creating her own theater."[18] Among her most notable performances was a 1975 free-form dance, in a modern style, set to Ravel’s Boléro. In it, she dances a solo piece on an elevated round stage, surrounded and accompanied by 40 male dancers. One reviewer wrote, "Words cannot compare to the majesty and raw beauty of Plisetskaya's performance:"[19]

What makes the piece so compelling is that although Plisetskaya may be accompanied by dozens of other dancers mirroring her movement, the first and only focus is on the prima ballerina herself. Her continual rocking and swaying at certain points, rhythmically timed to the syncopation of the orchestra, create a mesmerizing effect that demonstrated an absolute control over every nuance of her body, from the smallest toe to her fingertips, to the top of her head.[19]

Performances

"She burst like a flame on the American scene in 1959. Instantly she became a darling to the public and a miracle to the critics. She was compared to Maria Callas, Theda Bara and Greta Garbo."

Sarah Montague[20]

She created a number of leading roles, including ones in Lavrovsky's Stone Flower (1954), Moiseyev's Spartacus (1958), Grigorovich’s Moscow version of The Stone Flower (1959), Aurora in Grigorovich's staging The Sleeping Beauty (1963), Grigorovich's Moscow version of The Legend of Love (1965), the title role in Alberto Alonso's Carmen Suite (1967), Petit's La Rose malade (Paris, 1973), Bejart's Isadora (Monte Carlo, 1976) and his Moscow staging of Leda (1979), Granero's Maria Estuardo (Madrid, 1988), and Lopez's El Renedero (Buenos Aires, 1990).[15]

After performing in Spartacus during her 1959 U.S. debut tour, Life magazine, in its issue featuring the Bolshoi, rated her second only to Galina Ulanova.[21] Spartacus became a significant ballet for the Bolshoi, with one critic describing their "rage to perform", personified by Plisetskaya as ballerina, "that defined the Bolshoi."[10] During her travels she also appeared as guest artist with the Paris Opera Ballet, Ballet National de Marseilles, and Ballet of the 20th Century in Brussels.[15]

By 1962, following Ulanova's retirement, Plisetskaya embarked on another three-month world tour. As a performer, notes Homans, she "excelled in the hard-edged, technically demanding roles that Ulanova eschewed, including Raymonda, the black swan in Swan Lake, and Kitri in Don Quixote."[10] In her performances, Plisetskaya was "unpretentious, refreshing, direct. She did not hold back."[10] Ulanova added that Plisetskaya's "artistic temperament, bubbling optimism of youth reveal themselves in this ballet with full force."[20] World-famous impresario Sol Hurok said that Plisetskaya was the only ballerina after Pavlova who gave him "a shock of electricity" when she came on stage.[20] Rudolf Nureyev watched her debut as Kitri in Don Quixote and told her afterwards, "I sobbed from happiness. You set the stage on fire."[4][22]

At the conclusion of one performance at the Metropolitan Opera, she received a half-hour ovation. Choreographer Jerome Robbins, who had just finished the Broadway play, West Side Story, told her that he "wanted to create a ballet especially for her."[5]

Plisetskaya's most acclaimed roles included Odette-Odile in Swan Lake (1947) and Aurora in Sleeping Beauty (1961). Her dancing partner in Swan Lake states that for twenty years, he and Plisetskaya shared the world stage with that ballet, with her performance consistently producing "the most powerful impression on the audience."[23]

Equally notable were her ballets as The Dying Swan. Critic Walter Terry described one performance: "What she did was to discard her own identity as a ballerina and even as a human and to assume the characteristics of a magical creature. The audience became hysterical, and she had to perform an encore."[20] She danced that particular ballet until her late 60s, giving one of her last performances of it in the Philippines, where similarly, the applause wouldn't stop until she came out and performed an encore.[24]

Novelist Truman Capote remembered a similar performance in Moscow, seeing "grown men crying in the aisles and worshiping girls holding crumpled bouquets for her." He saw her as "a white spectre leaping in smooth rainbow arcs", with "a royal head". She said of her style that "the secret of the ballerina is to make the audience say, 'Yes, I believe.'"[20]

Fashion designers Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Cardin considered Plisetskaya one of their inspirations, with Cardin alone having traveled to Moscow over 30 times just to see Plisetskaya perform.[24][25] She credits Cardin's costume designs for the success and recognition she received for her ballets of Anna Karenina, The Seagull, and Lady with the Dog. She recalls his reaction when she initially suggested he design one of her costumes: "Cardin's eyes lit up like batteries. As if an electrical current passed through them."[13]: 170 Within a week he had created a design for Anna Karenina, and over the course of her career he created ten different costumes for just Karenina.[26]

“She was, and still is, a star, ballet's monstre sacré, the final statement about theatrical glamour, a flaring, flaming beacon in a world of dimly twinkling talents, a beauty in the world of prettiness”.

Financial Times, 2005[27]

In 1967, she performed as Carmen in the Carmen Suite, choreographed specifically for her by Cuban choreographer Alberto Alonso. The music was re-scored from Bizet’s original by her husband, Rodion Shchedrin, and its themes were re-worked into a "modernist and almost abstract narrative."[28] Dancer Olympia Dowd, who performed alongside her, writes that Plisetskaya’s dramatic portrayal of Carmen, her favorite role, made her a legend, and soon became a "landmark" in the Bolshoi's repertoire.[29] Her Carmen, however, at first "rattled the Soviet establishment," which was "shaken with her Latin sensuality."[30] She was aware that her dance style was radical and new, saying that "every gesture, every look, every movement had meaning, was different from all other ballets... The Soviet Union was not ready for this sort of choreography. It was war, they accused me of betraying classical dance."[31]

Some critics outside of Russia saw her departure from classical styles as necessary to the Bolshoi's success in the West. New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff observed, "Without her presence, their poverty of movement invention would make them untenable in performance. It is a tragedy of Soviet ballet that a dancer of her singular genius was never extended creatively.”[18] A Russian news commentator wrote, she "was never afraid to bring ardor and vehemence onto the stage," contributing to her becoming a "true queen of the Bolshoi."[30] Her life and work was described by the French ballet critic André Philippe Hersin as "genius, audacity and avant-garde."[32]

Acting and choreography

After Galina Ulanova left the stage in 1960, Maya Plisetskaya was proclaimed the prima ballerina assoluta of the Bolshoi Theatre. In 1971, her husband Shchedrin wrote a ballet on the same subject, where she would play the leading role. Anna Karenina was also her first attempt at choreography.[33] Other choreographers who created ballets for her include Yury Grigorovich, Roland Petit, Alberto Alonso, and Maurice Béjart with "Isadora". She created The Seagull and Lady with a Lapdog. She starred in the 1961 film, The Humpbacked Horse, and appeared as a straight actress in several films, including the Soviet version of Anna Karenina (1968). Her own ballet of the same name was filmed in 1974.[citation needed]

While on tour in the United States in 1987, Plisetskaya gave master classes at the David Howard Dance Center. A review in New York magazine noted that although she was 61 when giving the classes, “she displayed the suppleness and power of a performer in her physical prime.”[34] In October that year she performed with Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov for the opening night of the season with the Martha Graham Dance Company in New York.[35]

Plisetskaya's husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin, wrote the score to a number of her ballets, including Anna Karenina, The Sea Gull, Carmen, and Lady with a Small Dog. In the 1980s, he was considered the successor to Shostakovich, and became the Soviet Union's leading composer.[36] Plisetskaya and Shchedrin spent time abroad, where she worked as the artistic director of the Rome Opera Ballet in 1984–85, then the Spanish National Ballet of Madrid from 1987 to 1989. She retired as a soloist for the Bolshoi at age 65, and on her 70th birthday, she debuted in Maurice Béjart's piece choreographed for her, "Ave Maya". Since 1994, she has presided over the annual international ballet competitions, called Maya. And in 1996 she was named President of the Imperial Russian Ballet.[37]

She was ballet director of the Rome Opera (1983–84), and artistic director of Ballet del Teatro Lirico Nacional in Madrid (1987–90). She was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts in 2005 with the ballerina Tamara Rojo also. She was awarded the Spanish Gold Medal of Fine Art. In 1996 she danced the Dying Swan, her signature role, at a gala in her honor in St. Petersburg.[15]

On her 80th birthday, the Financial Times wrote:

She was, and still is, a star, ballet's monstre sacre, the final statement about theatrical glamour, a flaring, flaming beacon in a world of dimly twinkling talents, a beauty in the world of prettiness."[38]

In 2006, Emperor Akihito of Japan presented her with the Praemium Imperiale, informally considered a Nobel Prize for Art.[citation needed]

Death

Plisetskaya died in Munich, Germany, on 2 May 2015 from a heart attack.[18][39] Plisetskaya was survived by her husband, and a brother, former dancer Azari Plisetsky, a teacher of choreography at the Bejart Ballet in Lausanne, Switzerland.[18] According to her last will and testament, she was to be cremated, and after the death of her widower, Rodion Shchedrin, who is also to be cremated, their ashes are to be combined and spread over Russia.[40]

Russian President Vladimir Putin expressed his condolences, and Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said that "a whole era of ballet was gone" with Plisetskaya.[41] Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko extended condolences to her family and friends:

The passing of great Maya Mikhailovna [Plisetskaya] whose creative work embodied the whole cultural era is an irretrievable loss for Russian and world art. Her brilliant choreography and wonderful grace, fantastic power of dramatic identification and outstanding mastery dazzled the audience. Thanks to her selfless service to art and commitment to the stage, she was respected all over the world.[42]

Tributes

- Brazilian mural artist Eduardo Kobra painted a 40-foot tall mural of Plisetskaya in 2013, located in Moscow's central theater district, near the Bolshoi Theatre.[43]

- Conductor and artistic director Valery Gergiev, who was a close friend of Plisetskya, gave a concert in Moscow on November 18, 2015, dedicated to her memory.[44]

- On November 20, 2015, the government of Russia named a square in her honor in central Moscow, on Ulitsa Bolshaya Dmitrovka, near the Bolshoi Theatre. A bronze plaque affixed at the square included an engraving: “Maya Plisetskaya Square is named after the outstanding Russian ballerina. Opened Nov. 20, 2015.”[45]

- In St.Petersburg, the Mariinsky Theater Symphony Orchestra will pay homage to Plisetskaya’s memory with a concert on December 27, 2015. It will be conducted by Valery Gergiev and include a performance with ballet dancer Diana Vishneva.[44] The Mariinsky Ballet later performed a four-program "Tribute of Maya Plisetskaya" at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in February 2016.[46]

- The Bolshoi Theater will perform a concert in memory of Plisetskaya at the London Coliseum on March 6, 2016.[47]

Personal life

Career friendships

Plisetskaya's tour manager, Maxim Gershunoff, who also helped promote the Soviet/American Cultural Exchange Program, describes her as "not only a great artist, but also very realistic and earthy ... with a very open and honest outlook on life."[48]

During Plisetskaya's tours abroad she became friends with a number of other theater and music artists, including composer and pianist Leonard Bernstein, with whom she remained friends until his death. Pianist Arthur Rubinstein, also a friend, was able to converse with her in Russian. She visited him after his concert performance in Russia.[13]: 202 Novelist John Steinbeck, while at their home in Moscow, listened to her stories of the hardship of becoming a ballerina, and told her that the backstage side of ballet could make for a "most interesting novel".[13]: 203

In 1962, the Bolshoi was invited to perform at the White House by president John F. Kennedy, and Plisetskaya recalled that first lady Jacqueline Kennedy greeted her by saying "You're just like Anna Karenina."[13]: 222

While in France in 1965, Plisetskaya was invited to the home of Russian artist Marc Chagall and his wife. Chagall had moved to France to study art in 1910. He asked her if she wouldn't mind creating some ballet poses to help him with his current project, a mural for the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York, which would show various images representing the arts. She danced and posed in various positions as he sketched, and her images were used on the mural, "at the top left corner, a colorful flock of ballerinas".[13]: 250

Plisetskaya made friends with a number of celebrities and notable politicians who greatly admired and followed her work. She met Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman, then living in the U.S., after a performance of Anna Karenina. Bergman told her that both their photographs, taken by noted photographer Richard Avedon, appeared on the same page in Vogue magazine. Bergman suggested she "flee Communism", recalled Plisetskaya, telling her "I will help you."[13]: 222

Actress Shirley MacLaine once held a party for her and the other members of the Bolshoi. She remembered seeing her perform in Argentina when Plisetskaya was sixty-five, and writes "how humiliating it was that Plisetskaya had to dance on a vaudeville stage in South America to make ends meet."[49] Dancer Daniel Nagrin noted that she was a dancer who "went on to perform to the joy of audiences everywhere while simultaneously defying the myth of early retirement."[50]

MacLaine's brother, actor Warren Beatty, is said to have been inspired by their friendship, which led him to write and produce his 1981 film Reds, about the Russian Revolution. He directed the film and costarred with Diane Keaton. He first met Plisetskaya at a reception in Beverly Hills, and, notes Beatty's biographer Peter Biskind, "he was smitten" by her "classic dancer's" beauty.[51]

Plisetskaya became friends with film star Natalie Wood and her sister, actress Lana Wood. Wood, whose parents immigrated from Russia, greatly admired Plisetskaya, and once had an expensive custom wig made for her to use in the Spartacus ballet. They enjoyed socializing together on Wood's yacht.[48]

Friendship with Robert F. Kennedy

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the younger brother to president John F. Kennedy, befriended Plisetskaya, with whom he shared the birth date of 20 November 1925. She was invited to gatherings with Kennedy and his family at their estate on Cape Cod in 1962. They later named their sailboat Maya, in her honor.[48]

As the Cuban Missile Crisis had ended a few weeks earlier, at the end of October, 1962, U.S. and Soviet relations were at a low point. Diplomats of both countries considered her friendship with Kennedy to be a great benefit to warmer relations, after weeks of worrisome military confrontation. Years later, when they met in 1968, he was then campaigning for the presidency, and diplomats again suggested that their friendship would continue to help relations between the two countries. Plisetskaya summarizes Soviet thoughts on the matter:

Maya Plisetskaya should bring the candidate presents worthy of the great moment. Stun the future president with Russian generosity to continue and deepen contacts and friendship.[13]: 265

Of their friendship, Plisetskaya wrote in her autobiography:

With me Robert Kennedy was romantic, elevated, noble, and completely pure. No seductions, no passes.[13]: 265

Robert Kennedy was assassinated just days before he was to see Plisetskaya again in New York. Gershunoff, Plisetskaya's manager at the time, recalls that on the day of the funeral, most of the theaters and concert halls in New York City went "dark", closed in mourning and respect. The Bolshoi likewise planned to cancel their performance, but they decided instead to do a different ballet than planned, one dedicated to Kennedy. Gershunoff describes that evening:

The most appropriate way to open such an evening would be for the great Plisetskaya to perform The Dying Swan, which normally would close an evening’s program to thunderous applause with stamping feet, and clamors for an encore.... This assignment created an emotional burden for Maya. She really did not want to dance that work that night ... I thought it was best for me to remain backstage in the wings. That turned out to be one of the most poignant moments I have ever experienced. Replacing the usual thunderous audience applause at the conclusion, there was complete silence betokening the feelings of a mourning nation in the packed, cavernous Metropolitan Opera House. Maya came off the stage in tears, looked at me, raised her beautiful arms and looked upward. Then disappeared into her dressing room.[48]

Awards and honors

Plisetskaya was honored on numerous occasions for her skills:[37]

Russia

- Order of Merit for the Fatherland

- 1st class (20 November 2005) – for outstanding contribution to the development of domestic and international choreographic art, many years of creative activity[citation needed]

- 2nd class (18 November 2000) – for outstanding contribution to the development of choreographic art

- 3rd class (21 November 1995) – for outstanding contributions to national culture and a significant contribution to contemporary choreographic art

- 4th class (9 November 2010) – for outstanding contribution to the development of national culture and choreography, many years of creative activity[citation needed]

- Made an honorary professor at Moscow State University in 1993[52]

Soviet Union

- Hero of Socialist Labour (1985)

- Three Orders of Lenin (1967, 1976, 1985)

- Lenin Prize (1964)

- People's Artist of USSR (1959)

- People's Artist of RSFSR (1956)

- Honoured Artist of the RSFSR (1951)

Other decorations

- Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France, 1984)[52]

- Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain)[citation needed]

- Commander of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas[citation needed]

- Great Commander's Cross of the Order for Merits to Lithuania (2003)[citation needed]

- Gold Medal of Gloria Artis (Poland, 2008)[53]

- Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd class (Japan, 2011)[citation needed]

- Officer of the Légion d'honneur (France, 2012; Knight: 1986)

Awards

- First prize, Budapest International Competition (1949)

- Anna Pavlova Prize, Paris Academy of Dance (1962)

- Gold Prize, Slovenia, 2000.

- "Doctor of the Sorbonne" in 1985[52]

- Gold Medal of Fine Arts of Spain (1991)[52]

- Triumph Prize, 2000.

- Premium "Russian National Olympus" (2000)[citation needed]

- Prince of Asturias Award (2005, Spain)

- Imperial Prize of Japan (2006)[52]

See also

References

- ^ Maya Plisetskaya profilke, viola.bz; accessed 2 May 2015.

- ^ Plisetskaya and Shchedrin settle in Lithuania, upi.com; accessed 4 May 2015.

- ^ Two greats of world ballet win Spanish Nobels, expatica.com; accessed 4 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Maya Plisetskaya: Ballerina whose charisma and talent helped her fight the Soviet authorities and achieve international fame", The Independent, U.K. 5 May 2015

- ^ a b c d e Caute, David. The Dancer Defects: The Struggle for Cultural Supremacy During the Cold War, Oxford Univ. Press (2003) p. 489

- ^ "Maya Plisetskaya, ballerina - obituary", Telegraph, May 4, 2015

- ^ Current Biography Yearbook, H. W. Wilson Co., 1964, p. 331.

- ^ a b Miller, Jack (1984). Jews in Soviet Culture. Transaction Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 0-87855-495-5.

- ^ Popovich, Irina. "Maya Plisetskaya: A Balletic Lethal Weapon", The Russia Journal, Issue 10, May 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Homans, Jennifer. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet, Random House (2010) pp. 383-386

- ^ a b Eaton, Katherine Bliss (2004). Daily Life in the Soviet Union. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31628-7.

- ^ They were sent to ALZHIR camp, a Russian acronym for the Akmolinskii Camp for Wives of Traitors of the Motherland, "enemies of the people" [1] near Akmolinsk

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Plisetskaya, Maya (2001). I, Maya Plisetskaya. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08857-4.

- ^ Dagens Næringsliv, the article "Svanens død" (english: "Death of the swan", p. 19, 9th May 2015

- ^ a b c d e Craine, Debra & Mackrell, Judith. The Oxford Dictionary of Dance, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2010; pp. 352-353

- ^ a b Ezrahi, Christina. Swans of the Kremlin, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press (2012) p. 68, 142

- ^ Taubman, William; Khrushchev, Sergei; Gleason, Abbott; Gehrenbeck, David; Kane, Eileen; Bashenko, Alla (2000). Nikita Khrushchev. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07635-5.

- ^ a b c d "Maya Plisetskaya, Ballerina Who Embodied Bolshoi, Dies at 89", New York Times, 2 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Master Class: Maya Plisetskaya's Bolero", Artful Intel, 25 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Montague, Sarah. The Ballerina, Universe Books, N.Y. (1980) pp. 46-49

- ^ Life magazine, 23 February 1959.

- ^ "Maya Plisetskaya in Don Quixote ca 1959" on YouTube

- ^ "Plisetskaya-AVE MAYA-documentary film" on YouTube, translated from Russian

- ^ a b "Remembering The Great Maya Plisetskaya", Inquirer, Philippines, July 6, 2015

- ^ "Russia mourns its ballet legend rebel Plisetskaya", AFP, May 3, 2015

- ^ "BALLERINA MAYA PLISETSKAYA AND FASHION AT HER POINTE SHOES", Cassandra Fox, May 3, 2015

- ^ "Endless dance of Maya Plisetskaya", Russia Beyond the Headlines, May 6, 2015

- ^ Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation, Routledge (2006) p. 164

- ^ Dowd, Olympia. A Young Dancer's Apprenticeship: On Tour with the Moscow City Ballet, Twenty-first Century Books (2003) p. 71

- ^ a b "Moscow Honors Bolshoi's 'True Queen'", Washington Post, 20 November 2005.

- ^ "Russian ballet great Maya Plisetskaya dies – Bolshoi", GMG News, Agence France-Presse, 2 May 2015

- ^ "Endless dance of Maya Plisetskaya", Russia Beyond the Headlines, May 6, 2015

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (2003). Anna Karenina. Mandelker, Amy; Garnett, Constance. Spark Educational Publishing. ISBN 1-59308-027-1.

- ^ New York magazine, 22 June 1987, p. 65

- ^ New York magazine, 21 September 1987, p. 100

- ^ New York magazine, 28 March 1988, p. 99

- ^ a b Sleeman, Elizabeth (2001). The International Who's Who of Women (3rd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-122-7.

- ^ Crisp, Clement (18 November 2005). "Mayan goddess". Financial Times. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ Скончалась балерина Майя Плисецкая (in Russian). ITAR TASS. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Плисецкая завещала развеять ее прах над Россией Info re last will testament of Plisetskaya, interfax.ru, 3 May 2015.Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Ballerina Maya Plisetskaya dies of heart attack at 89", Pravda, May 2, 2015

- ^ "Lukashenko extends condolences over passing of Maya Plisetskaya", Belarusian News, 5 May 2015

- ^ "Gorgeous Mural Honors Russian Ballerina Maya Plisetskaya", My Modern Net, Oct. 21, 2013

- ^ a b "Gergiev to pay homage to memory of Maya Plisetskaya with concert in Moscow", Tass, Nov. 18, 2015

- ^ "Moscow Square Named in Honor of Ballerina Plisetskaya", The Moscow Times, Nov. 20, 2015

- ^ "Review: Mariinsky Celebrates a Prima Ballerina", New York Times, Feb. 26, 2016

- ^ "London to host gala in memory of Maya Plisetskaya", Russia Beyond the Headlines, May 6, 2015

- ^ a b c d Gershunoff, Maxim. It's Not All Song and Dance: A Life Behind the Scenes in the Performing Arts, Hal Leonard Corp. (2005) pp. 61,65,74

- ^ MacLaine, Shirley. Out on a Leash: Exploring the Nature of Reality and Love, Simon & Schuster (2003) p. 126

- ^ Nagrin, Daniel. How to Dance Forever: Surviving Against the Odds, HarperCollins (1988) p. 15

- ^ Biskind, Peter. Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America, Simon & Schuster (2010) p. 90

- ^ a b c d e "Died ballerina Maya Plisetskaya", TASS, May 2, 2015

- ^ Warszawa. Urodziny primadonny at the www.e-teatr.pl Template:Pl icon

External links

- Photo gallery

- Maya Plisetskaya at IMDb

- "Maya Plisetskaya Dances Ballet, biographical documentary, 1964" on YouTube, 1 hr. 11 min.

- "Legendary performances: Maya Plisetskaya" on YouTube, documentary biography, 1 hr. 20 min.

- "Maya Plisetskaya in 'Swan Lake' on YouTube, 3 1/2 min.

- Maya Plisetskaya, Nicolai Fadeyechev and Alexander Godunov in "Carmen-suite" on YouTube, filmed at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, 1987, 43 min.

- "Maya Plisetskaya in 'Spartacus'" on YouTube, 2 1/2 min.

- "Maya Plisetskaya - Bolero, by Ravel", video, 20 min.

- Video: Excerpt from Maya's "Dance Studies" on YouTube

- 1925 births

- 2015 deaths

- Prima ballerina assolutas

- Lithuanian choreographers

- Soviet choreographers

- Spanish choreographers

- Lithuanian Jews

- Soviet Jews

- Russian Jews

- Jewish dancers

- Spanish Jews

- Lithuanian ballerinas

- Soviet ballerinas

- Spanish ballerinas

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 1st class

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 3rd class

- Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 4th class

- People's Artists of the USSR

- Lenin Prize winners

- Heroes of Socialist Labour

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Honored Artists of the RSFSR

- People's Artists of Russia

- Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Commanders of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd class

- Commander's Crosses of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas

- Commander's Grand Crosses of the Order for Merits to Lithuania

- People from Moscow

- Russian emigrants to Spain

- Russian emigrants to Germany

- Plisetski–Messerer family