Mount Tambora

| Mount Tambora | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the caldera of Mount Tambora | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,850 m (9,350 ft)[1][2] |

| Prominence | 2,850 m (9,350 ft)[1][3] |

| Listing | Ultra Ribu |

| Geography | |

| Location | Sumbawa, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia |

| Region | ID |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | 57000 years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano/Caldera |

| Last eruption | 1967 ± 20 years[1] |

Mount Tambora (or Tamboro) is an active stratovolcano on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. Sumbawa is flanked both to the north and south by oceanic crust, and Tambora was formed by the active subduction zone beneath it. This raised Mount Tambora as high as 4,300 m (14,100 ft),[4] making it, in the 18th century, one of the tallest peaks in the Indonesian archipelago. After a large magma chamber inside the mountain filled over the course of several decades, volcanic activity reached a historic climax in the eruption of 10 April 1815.[5] This eruption was approximately VEI-7, the only eruption unambiguously confirmed of that size since the Lake Taupo eruption in about 180 CE.[6] (The Heaven Lake eruption of Baekdu Mountain in c. 969 CE may have also been VEI-7.)

With an estimated ejecta volume of 160 km3 (38 cu mi), Tambora's 1815 outburst was the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history. The explosion was heard on Sumatra island more than 2,000 km (1,200 mi) away. Heavy volcanic ash falls were observed as far away as Borneo, Sulawesi, Java and Maluku islands. Most deaths from the eruption were from starvation and disease, as the eruptive fallout ruined agricultural productivity in the local region. The death toll was at least 71,000 people, of whom 11,000–12,000 were killed directly by the eruption;[6] the often-cited figure of 92,000 people killed is believed to be overestimated.[7]

The eruption caused global climate anomalies that included the phenomenon known as "volcanic winter": 1816 became known as the "Year Without a Summer" because of the effect on North American and European weather. Crops failed and livestock died in much of the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in the worst famine of the 19th century.[6]

During an excavation in 2004, a team of archaeologists discovered cultural remains buried by the 1815 eruption.[8] They were kept intact beneath the 3 m (9.8 ft) deep pyroclastic deposits. At the site, dubbed the Pompeii of the East, the artifacts were preserved in the positions they had occupied in 1815.

Geographical setting

Mount Tambora is located on Sumbawa Island, part of the Lesser Sunda Islands. It is a segment of the Sunda Arc, a string of volcanic islands that forms the southern chain of the Indonesian archipelago.[9] Tambora forms its own peninsula on Sumbawa, known as the Sanggar peninsula. At the north of the peninsula is the Flores Sea, and at the south is Saleh Bay, 86 km (53 mi) long and 36 km (22 mi) wide. At the mouth of Saleh Bay there is a 30,000 hectares islet called Moyo (Indonesian: Pulau Moyo) which has a guest shelter or luxurious resort where celebrities such as Princess Diana once stayed.[10]

Besides its interest for seismologists and volcanologists, who monitor the mountain's activity, Mount Tambora is an area of scientific studies for archaeologists and biologists. The mountain also attracts tourists for hiking and wildlife activities.[11][12] The two nearest cities are Dompu and Bima. There are three concentrations of villages around the mountain slope. At the east is Sanggar village, to the northwest are Doro Peti and Pesanggrahan villages, and to the west is Calabai village.

There are three ascent routes to reach the caldera. The first route starts from Doro Mboha village south of the mountain. This route follows a paved road through a cashew plantation until it reaches 1,150 m (3,770 ft) above sea level. The end of this route is the southern part of the caldera at 1,950 m (6,400 ft), reachable by a hiking track.[13] This location is usually used as a base camp to monitor the volcanic activity, because it only takes one hour to reach the caldera. The second route is located in southwest of the mountain start from Doro Peti village, the Tambora volcanic monitoring station is located in this village. The third route starts from Pancasila village northwest of the mountain. This route passing through a coffee plantation. Using the third route, the caldera is accessible only by foot.[13] The highest point of Tambora located on a hill near the westen rim of the caldera.

In August 2011, the alert level for the volcano was raised from Level I to Level II after increasing activity was reported in the caldera, including earthquakes and smoke emissions.[14] In September 2011 the alert level was raised to Level III after further increases in activity.[15]

Geological history

Formation

Tambora lies 340 km (210 mi) north of the Java Trench system and 180–190 km (110–120 mi) above the upper surface of the active north-dipping subduction zone. Sumbawa island is flanked to both the north and south by the oceanic crust.[16] The convergence rate is 7.8 cm (3.1 in) per year.[17] Tambora is estimated to have formed around 57,000 years ago.[5] Depositing its strata has drained off a large magma chamber inside the mountain. The Mojo islet was formed as part of this geological process in which Saleh Bay, collapsing into the caldera of the drained magma chamber, first appeared as a sea basin, about 25,000 years ago.[5]

According to a geological survey, prior to the 1815 eruption Tambora had the shape of a typical stratovolcano, with a high symmetrical volcanic cone and a single central vent.[18] The diameter at the base is 60 km (37 mi).[9] The central vent emitted lava frequently, which cascaded down a steep slope.

Since the 1815 eruption, the lowermost portion contains deposits of interlayered sequences of lava and pyroclastic materials. The 1–4 m (3.3–13.1 ft) thick lava flows constitute approximately 40% of the layers' thickness.[18] Thick scoria beds were produced by the fragmentation of lava flows. Within the upper section, the lava is interbedded with scoria, tuffs and pyroclastic flows and falls.[18] There are at least twenty subsidiary or parasitic cones.[17] Some of them have names: Tahe, 844 m (2,769 ft); Molo, 602 m (1,975 ft); Kadiendinae; Kubah, 1,648 m (5,407 ft); and Doro Api Toi. Most of these parasitic cones have produced andesitic lavas.

Eruptive history

Use of the radiocarbon dating technique has established the dates of three of Mount Tambora's eruptions prior to the 1815 eruption. The magnitudes of these eruptions are unknown.[19] The estimated dates are 3910 BCE ± 200 years, 3050 BCE and 740 CE ± 150 years. They were all explosive central vent eruptions with similar characteristics, except the lattermost eruption had no pyroclastic flows.

In 1812, Mount Tambora entered a period of high activity, with its climactic eruption being the catastrophic explosive event of April 1815.[19] The VEI 7 eruption had a total tephra ejecta volume of 160 km3 (38 cu mi).[19] It was an explosive central vent eruption with pyroclastic flows and a caldera collapse, causing tsunamis and extensive land and property damage. It had a long-term effect on global climate. This activity ceased on 15 July 1815.[19] Follow-up activity was recorded in August 1819 consisting of a small eruption (VEI = 2) with flames and rumbling aftershocks, and was considered to be part of the 1815 eruption sequence.[6] Around 1880 ± 30 years, Tambora went into eruption again, but only inside the caldera.[19] Small lava flows and lava dome extrusions were formed. This eruption (VEI = 2) created the Doro Api Toi parasitic cone inside the caldera.[20]

Mount Tambora is still active. Minor lava domes and flows have been extruded on the caldera floor during the 19th and 20th centuries.[1] The last eruption was recorded in 1967.[19] However, it was a very small, non-explosive eruption (VEI = 0).

1815 eruption

Chronology of the eruption

Mount Tambora experienced several centuries of inactive dormancy before 1815, as the result of the gradual cooling of hydrous magma in a closed magma chamber.[9] Inside the chamber at depths between 1.5–4.5 km (0.93–2.80 mi), the exsolution of a high-pressure fluid magma formed during cooling and crystallisation of the magma. Overpressure of the chamber of about 4,000–5,000 bar (58,000–73,000 psi) was generated, and the temperature ranged from 700–850 °C (1,292–1,562 °F).[9] In 1812, the caldera began to rumble and generated a dark cloud.[4]

On 5 April 1815, a moderate-sized eruption occurred, followed by thunderous detonation sounds, heard in Makassar on Sulawesi, 380 km (240 mi) away, Batavia (now Jakarta) on Java 1,260 km (780 mi) away, and Ternate on the Molucca Islands 1,400 km (870 mi) away. On the morning of 6 April, volcanic ash began to fall in East Java with faint detonation sounds lasting until 10 April. What was first thought to be sound of firing guns was heard on 10 April on Sumatra island more than 2,600 km (1,600 mi) away.[21]

At about 7 p.m. on 10 April, the eruptions intensified.[4] Three columns of flame rose up and merged.[21] The whole mountain was turned into a flowing mass of "liquid fire".[21] Pumice stones of up to 20 cm (7.9 in) in diameter started to rain down at approximately 8 p.m., followed by ash at around 9–10 p.m. Pyroclastic flows cascaded down the mountain to the sea on all sides of the peninsula, wiping out the village of Tambora. Loud explosions were heard until the next evening, 11 April. The ash veil had spread as far as West Java and South Sulawesi. A "nitrous" odour was noticeable in Batavia and heavy tephra-tinged rain fell, finally receding between 11 and 17 April.[4]

The first explosions were heard on this Island in the evening of 5 April, they were noticed in every quarter, and continued at intervals until the following day. The noise was, in the first instance, almost universally attributed to distant cannon; so much so, that a detachment of troops were marched from Djocjocarta, in the expectation that a neighbouring post was attacked, and along the coast boats were in two instances dispatched in quest of a supposed ship in distress.

—Sir Stamford Raffles' memoir.[21]

The explosion is estimated to have been VEI 7.[22] It had roughly four times the energy of the 1883 Krakatoa eruption, meaning that it was equivalent to an 800 Mt (3.3×1012 MJ) explosion. An estimated 160 km3 (38 cu mi) of pyroclastic trachyandesite was ejected, weighing approximately 1.4×1014 kg (3.1×1014 lb) (see above). This has left a caldera measuring 6–7 km (3.7–4.3 mi) across and 600–700 m (2,000–2,300 ft) deep.[4] The density of fallen ash in Makassar was 636 kg/m² (130.3 lb/sq ft).[23] Before the explosion, Mount Tambora was approximately 4,300 m (14,100 ft) high,[4] one of the tallest peaks in the Indonesian archipelago. After the explosion, it now measures only 2,851 m (9,354 ft).[24]

The 1815 Tambora eruption is the largest observed eruption in recorded history (see Table I, for comparison).[4][6] The explosion was heard 2,600 km (1,600 mi) away, and ash fell at least 1,300 km (810 mi) away.[4] Pitch darkness was observed as far away as 600 km (370 mi) from the mountain summit for up to two days. Pyroclastic flows spread at least 20 km (12 mi) from the summit. Due to the eruption, Indonesia's islands were struck by tsunami waves reaching a height of up to 4 m (13 ft).

Aftermath

On my trip towards the western part of the island, I passed through nearly the whole of Dompo and a considerable part of Bima. The extreme misery to which the inhabitants have been reduced is shocking to behold. There were still on the road side the remains of several corpses, and the marks of where many others had been interred: the villages almost entirely deserted and the houses fallen down, the surviving inhabitants having dispersed in search of food.

...

Since the eruption, a violent diarrhoea has prevailed in Bima, Dompo, and Sang'ir, which has carried off a great number of people. It is supposed by the natives to have been caused by drinking water which has been impregnated with ashes; and horses have also died, in great numbers, from a similar complaint.—Lt. Philips, ordered by Sir Stamford Raffles to go to Sumbawa.[21]

All vegetation on the island was destroyed. Uprooted trees, mixed with pumice ash, washed into the sea and formed rafts of up to 5 km (3.1 mi) across.[4] One pumice raft was found in the Indian Ocean, near Calcutta on 1 and 3 October 1815.[6] Clouds of thick ash still covered the summit on 23 April. Explosions ceased on 15 July, although smoke emissions were still observed as late as 23 August. Flames and rumbling aftershocks were reported in August 1819, four years after the event.

A moderate-sized tsunami struck the shores of various islands in the Indonesian archipelago on 10 April, with a height of up to 4 metres (13 ft) in Sanggar at around 10 p.m.[4] A tsunami of 1–2 m (3.3–6.6 ft) in height was reported in Besuki, East Java, before midnight, and one of 2 metres (6.6 ft) in height in the Molucca Islands. The total death-toll has been estimated at around 4,600.[25]

The eruption column reached the stratosphere, an altitude of more than 43 km (27 mi).[6] The coarser ash particles fell 1 to 2 weeks after the eruptions, but the finer ash particles stayed in the atmosphere from a few months up to a few years at an altitude of 10–30 km (6.2–18.6 mi).[4] Longitudinal winds spread these fine particles around the globe, creating optical phenomena. Prolonged and brilliantly coloured sunsets and twilights were frequently seen in London, England between 28 June and 2 July 1815 and 3 September and 7 October 1815.[4] The glow of the twilight sky typically appeared orange or red near the horizon and purple or pink above.

The estimated number of deaths varies depending on the source. Zollinger (1855) puts the number of direct deaths at 10,000, probably caused by pyroclastic flows. On Sumbawa island, there were 38,000 deaths due to starvation, and another 10,000 deaths occurred due to disease and hunger on Lombok island.[26] Petroeschevsky (1949) estimated about 48,000 and 44,000 people were killed on Sumbawa and Lombok, respectively.[27] Several authors use Petroeschevsky's figures, such as Stothers (1984), who cites 88,000 deaths in total.[4] However, Tanguy et al.. (1998) claimed Petroeschevsky's figures to be unfounded and based on untraceable references.[7] Tanguy revised the number solely based on two credible sources, q.e., Zollinger, who himself spent several months on Sumbawa after the eruption, and Raffles's notes.[21] Tanguy pointed out that there may have been additional victims on Bali and East Java because of famine and disease. Their estimate was 11,000 deaths from direct volcanic effects and 49,000 by post-eruption famine and epidemic diseases.[7] Oppenheimer (2003) stated a modified number of at least 71,000 deaths in total, as seen in Table I below.[6]

| Eruptions | Country | Location | Year | Column height (km) |

Volcanic Explosivity Index |

N. hemisphere summer anomaly (°C) |

Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Vesuvius | Italy | Mediterranean | 79 | 30 | 5 | ? | >2,000 |

| Hatepe (Taupo) | New Zealand | Pacific Ring of Fire | 186 | 51 | 7 | ? | ? |

| Baekdu | China / North Korea | Pacific Ring of Fire | 969 | 25 | 6–7 | ? | ? |

| Kuwae | Vanuatu | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1452 | ? | 6 | −0.5 | ? |

| Huaynaputina | Peru | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1600 | 46 | 6 | −0.8 | ≈1,400 |

| Tambora | Indonesia | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1815 | 43 | 7 | −0.5 | >71,000 |

| Krakatoa | Indonesia | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1883 | 36 | 6 | −0.3 | 36,600 |

| Santa María | Guatemala | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1902 | 34 | 6 | no anomaly | 7,000–13,000 |

| Novarupta | USA, Alaska | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1912 | 32 | 6 | −0.4 | 2 |

| Mt. St. Helens | USA, Washington | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1980 | 19 | 5 | no anomaly | 57 |

| El Chichón | Mexico | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1982 | 32 | 4–5 | YES | >2,000 |

| Nevado del Ruiz | Colombia | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1985 | 27 | 3 | no anomaly | 23,000 |

| Pinatubo | Philippines | Pacific Ring of Fire | 1991 | 34 | 6 | −0.5 | 1,202 |

Source: Oppenheimer (2003),[6] and Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program for VEI.[28]

Global effects

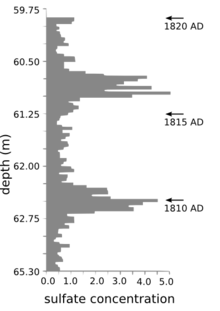

The 1815 eruption released sulphur into the stratosphere, causing a global climate anomaly. Different methods have estimated the ejected sulphur mass during the eruption: the petrological method; an optical depth measurement based on anatomical observations; and the polar ice core sulfate concentration method, using cores from Greenland and Antarctica. The figures vary depending on the method, ranging from 10 to 120 million tonnes.[6]

In the spring and summer of 1815, a persistent dry fog was observed in the northeastern United States. The fog reddened and dimmed the sunlight, such that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Neither wind nor rainfall dispersed the "fog". It was identified as a stratospheric sulfate aerosol veil.[6] In summer 1816, countries in the Northern Hemisphere suffered extreme weather conditions, dubbed the Year Without a Summer. Average global temperatures decreased about 0.4–0.7 °C (0.7–1.3 °F),[4] enough to cause significant agricultural problems around the globe. On 4 June 1816, frosts were reported in Connecticut, and by the following day, most of New England was gripped by the cold front. On 6 June 1816, snow fell in Albany, New York, and Dennysville, Maine.[6] Such conditions occurred for at least three months and ruined most agricultural crops in North America. Canada experienced extreme cold during that summer. Snow 30 cm (12 in) deep accumulated near Quebec City from 6 to 10 June 1816.

1816 was the second coldest year in the northern hemisphere since 1400 CE, after 1601 following the 1600 Huaynaputina eruption in Peru.[22] The 1810s are the coldest decade on record, a result of Tambora's 1815 eruption and other suspected eruptions somewhere between 1809 and 1810 (see sulfate concentration figure from ice core data). The surface temperature anomalies during the summer of 1816, 1817 and 1818 were −0.51 °C (−0.92 °F), −0.44 °C (−0.79 °F) and −0.29 °C (−0.52 °F), respectively.[22] As well as a cooler summer, parts of Europe experienced a stormier winter.

This pattern of climate anomaly has been blamed for the severity of typhus epidemic in southeast Europe and the eastern Mediterranean between 1816 and 1819.[6] The climate changes disrupted Indian monsoons causing three failed harvests and famine contributing to worldwide spread of a new strain of cholera originating in Bengal in 1816.[30] Much livestock died in New England during the winter of 1816–1817. Cool temperatures and heavy rains resulted in failed harvests in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Families in Wales travelled long distances as refugees, begging for food. Famine was prevalent in north and southwest Ireland, following the failure of wheat, oat and potato harvests. The crisis was severe in Germany, where food prices rose sharply. Due to the unknown cause of the problems, demonstrations in front of grain markets and bakeries, followed by riots, arson and looting, took place in many European cities. It was the worst famine of the 19th century.[6]

Archaeological work

See Tambora culture for details about 2004 work on exploring for villages and people lost at the time of the major eruption.

Ecosystem

A scientific team led by a Swiss botanist, Heinrich Zollinger, arrived on Sumbawa in 1847.[31] Zollinger's mission was to study the eruption scene and its effects on the local ecosystem. He was the first person to climb to the summit after the eruption. It was still covered by smoke. As Zollinger climbed up, his feet sank several times through a thin surface crust into a warm layer of powder-like sulphur. Some vegetation had re-established itself and a few trees were observed on the lower slope. A Casuarina forest was noted at 2,200–2,550 m (7,220–8,370 ft).[32] Several Imperata cylindrica grasslands were also found.

Rehabitation of the mountain began in 1907. A coffee plantation was started in the 1930s on the northwestern slope of the mountain, in the village of Pekat.[33] A dense rain forest, dominated by the pioneering tree, Duabanga moluccana, had grown at an altitude of 1,000–2,800 m (3,300–9,200 ft).[33] It covers an area up to 80,000 ha (200,000 acres). The rain forest was explored by a Dutch team, led by Koster and de Voogd in 1933.[33] From their accounts, they started their journey in a "fairly barren, dry and hot country", and then they entered "a mighty jungle" with "huge, majestic forest giants". At 1,100 m (3,600 ft), they entered a montane forest. Above 1,800 m (5,900 ft), they found Dodonaea viscosa dominated by Casuarina trees. On the summit, they found sparse Anaphalis viscida and Wahlenbergia.

In 1896, 56 species of birds were found, including the Crested White-eye.[34] Twelve further species were found in 1981. Several other zoological surveys followed, and found other bird species on the mountain, resulting in over 90 bird species discovered on Mount Tambora. Yellow-crested Cockatoos, Zoothera thrushes, Hill Mynas, Green Junglefowl and Rainbow Lorikeets are hunted for the cagebird trade by the local people. Orange-footed Scrubfowl are hunted for food. This bird exploitation has resulted in a decline in the bird population. The Yellow-crested Cockatoo is nearing extinction on Sumbawa island.[34]

Since 1972, a commercial logging company has been operating in the area, which poses a large threat to the rain forest. The logging company holds a timber-cutting concession for an area of 20,000 ha (49,000 acres), or 25% of the total area.[33] Another part of the rain forest is used as a hunting ground. In between the hunting ground and the logging area, there is a designated wildlife reserve where deer, water buffalos, wild pigs, bats, flying foxes, and various species of reptiles and birds can be found.[33]

Monitoring

Indonesia's population has been increasing rapidly since the 1815 eruption. As of 2006, the population of Indonesia has reached 222 million people,[35] of which 130 million are concentrated on Java.[36] A contemporary volcanic eruption as large as Tambora's 1815 eruption would cause catastrophic devastation with likely many more fatalities. Therefore, volcanic activity in Indonesia is continuously monitored, including that of Mount Tambora. Seismic activity in Indonesia is monitored by the Directorate of Vulcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, Indonesia. The monitoring post for Mount Tambora is located at Doro Peti village.[37] They focus on seismic and tectonic activities by using a seismograph. Since the 1880 eruption, there has been no significant increase in seismic activity.[38] However, monitoring is continuously performed inside the caldera, especially around the parasitic cone Doro Api Toi.

The directorate has defined a hazard mitigation map for Mount Tambora. Two zones are declared: the dangerous zone and the cautious zone.[37] The dangerous zone is an area that will be directly affected by an eruption: pyroclastic flow, lava flow and other pyroclastic falls. This area, including the caldera and its surroundings, covers up to 58.7 km2 (22.7 sq mi). Habitation of the dangerous zone is prohibited. The cautious zone includes areas that might be indirectly affected by an eruption: lahar flows and other pumice stones. The size of the cautious area is 185 km2 (71 sq mi), and includes Pasanggrahan, Doro Peti, Rao, Labuan Kenanga, Gubu Ponda, Kawindana Toi and Hoddo villages. A river, called Guwu, at the southern and northwest part of the mountain is also included in the cautious zone.[37]

See also

- List of volcanoes in Indonesia

- List of volcanic eruptions by death toll

- List of natural disasters

- Timetable of major worldwide volcanic eruptions

References

- ^ a b c d "Tambora". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b "Mountains of the Indonesian Archipelago". PeakList. PeakList.org. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ "Gunung Tambora". Peakbagger. PeakBagger.com. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Stothers, Richard B. (1984). "The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath". Science. 224 (4654): 1191–1198. Bibcode:1984Sci...224.1191S. doi:10.1126/science.224.4654.1191. PMID 17819476.

- ^ a b c

Degens, E.T. (1989). "Sedimentological events in Saleh Bay, off Mount Tambora". Netherlands Journal of Sea Research. 24 (4): 399–404. doi:10.1016/0077-7579(89)90117-8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). "Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815". Progress in Physical Geography. 27 (2): 230–259. doi:10.1191/0309133303pp379ra.

- ^ a b c

Tanguy, J.-C. (1998). "Victims from volcanic eruptions: a revised database". Bulletin of Volcanology. 60 (2): 137–144. Bibcode:1998BVol...60..137T. doi:10.1007/s004450050222.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "URI volcanologist discovers lost kingdom of Tambora" (Press release). University of Rhode Island. 27 February 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d Foden, J. (1986). "The petrology of Tambora volcano, Indonesia: A model for the 1815 eruption". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 27 (1–2): 1–41. Bibcode:1986JVGR...27....1F. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(86)90079-X.

- ^ "Sumbawa". Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^

"Hobi Mendaki Gunung – Menyambangi Kawah Raksasa Gunung Tambora" (in Indonesian). Sinar Harapan. 2003. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Potential Tourism as Factor of Economic Development in the Districts of Bima and Dompu" (PDF) (Press release). West and East Nusa Tenggara Local Governments. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ a b

Aswanir Nasution. "Tambora, Nusa Tenggara Barat" (in in Indonesian). Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, Indonesia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Peningkatan Status G. Tambora dari Normal ke Waspada[dead link]. Portal.vsi.esdm.go.id (2011-08-30). Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Evacuation Plans Prepped as Mount Tambora Alert Level Is Raised | The Jakarta Globe. GodLikeProductions.com. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^

Foden, J (1980). "The petrology and tectonic setting of Quaternary—Recent volcanic centres of Lombok and Sumbawa, Sunda arc". Chemical Geology. 30 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(80)90106-0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b

Sigurdsson, H. (1983). "Plinian and co-ignimbrite tephra fall from the 1815 eruption of Tambora volcano". Bulletin of Volcanology. 51 (4): 243–270. Bibcode:1989BVol...51..243S. doi:10.1007/BF01073515.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c

"Geology of Tambora Volcano". Vulcanological Survey of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f "Tambora – Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^

"Tambora Historic Eruptions and Recent Activities". Vulcanological Survey of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Raffles, S. 1830: Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, F.R.S. &c., particularly in the government of Java 1811–1816, and of Bencoolen and its dependencies 1817–1824: with details of the commerce and resources of the eastern archipelago, and selections from his correspondence. London: John Murray, cited by Oppenheimer (2003).

- ^ a b c

Briffa, K.R. (1998). "Influence of volcanic eruptions on Northern Hemisphere summer temperature over 600 years". Nature. 393 (6684): 450–455. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..450B. doi:10.1038/30943.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stothers, Richard B. (2004). "Density of fallen ash after the eruption of Tambora in 1815". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 134 (4): 343–345. Bibcode:2004JVGR..134..343S. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.03.010.

- ^

Monk, K.A. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd. p. 60. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ USGS account of historical volcanic induced tsunamis. Hvo.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Zollinger (1855): Besteigung des Vulkans Tamboro auf der Insel Sumbawa und Schilderung der Eruption desselben im Jahre 1815, Winterthur: Zurcher and Fürber, Wurster and Co., cited by Oppenheimer (2003).

- ^ Petroeschevsky (1949): A contribution to the knowledge of the Gunung Tambora (Sumbawa). Tijdschrift van het K. Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, Amsterdam Series 2 66, 688–703, cited by Oppenheimer (2003).

- ^ "Large Holocene Eruptions". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ^

Dai, J. (1991). "Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres). 96: 17, 361–17, 366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Peterson, Doug LAS News (Spring 2010) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign p. 11.

- ^ "Heinrich Zollinger". Zollinger Family History Research. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ Zollinger (1855) cited by Trainor (2002).

- ^ a b c d e de Jong Boers, Bernice (1995). "Mount Tambora in 1815: A Volcanic Eruption in Indonesia and its Aftermath". Indonesia. 60: 37–59. doi:10.2307/3351140. JSTOR 3351140.

- ^ a b Trainor, C.R. (2002). "Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade" (PDF). Forktail. 18: 49–61.

- ^

"Tingkat Kemiskinan di Indonesia Tahun 2005–2006" (PDF) (Press release) (in Indonesian). Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau. 1 September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Calder, Joshua (3 May 2006). "Most Populous Islands". World Island Information. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ^ a b c

"Tambora Hazard Mitigation" (in in Indonesian). Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^

"Tambora Geophysics" (in in Indonesian). Directorate of Volcanology and Geological Hazard Mitigation, Indonesia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

Further reading

- C.R. Harrington (ed.). The Year without a summer? : world climate in 1816, Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Nature, 1992. ISBN 0-660-13063-7

- Henry and Elizabeth Stommel. Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816 , the Year without a Summer, Newport RI. 1983. ISBN 0-915160-71-4

External links

Mount Tambora travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mount Tambora travel guide from Wikivoyage- "Indonesia Volcanoes and Volcanics". Cascades Volcano Observatory. USGS. Retrieved 19 March 2006.

- "Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia". Volcano World. Department of Geosciences at Oregon State University.

- "Informative website about Tambora volcano".

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA