Nasir al-Dawla

| Nasir al-Dawla | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amir al-umara (942–943) Emir of Mosul | |||||

Gold dinar minted at Baghdad in the names of Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla, 943/44 CE | |||||

| Reign | 935–967 | ||||

| Successor | Abu Taghlib | ||||

| Died | 968 or 969 Ardumusht | ||||

| Issue | Abu Taghlib, Abu'l-Fawaris, Abu'l-Qasim, Abu Abdallah al-Husayn, Abu Tahir Ibrahim | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Hamdanid | ||||

| Father | Abdallah ibn Hamdan | ||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||

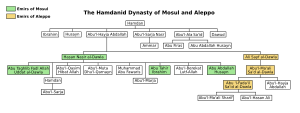

Abu Muhammad al-Hasan ibn Abi'l-Hayja Abdallah ibn Hamdan al-Taghlibi[note 1] (Arabic: أبو محمد الحسن بن أبي الهيجاء عبد الله بن حمدان التغلبي; died 968 or 969), more commonly known simply by his honorific of Nasir al-Dawla (ناصر الدولة, lit. 'Defender of the [Abbasid] Dynasty'), was the second Hamdanid ruler of the Emirate of Mosul, encompassing most of the Jazira.

As the senior member of the Hamdanid dynasty, he inherited the family power base around Mosul from his father, Abdallah ibn Hamdan, and was able to secure it against challenges by his uncles. Hasan became involved in the court intrigues of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, and, between 942 and 943, with the assistance of his brother Ali (known as Sayf al-Dawla), he established himself as amir al-umara, or de facto regent for the Abbasid caliph. He was driven back to Mosul by Turkish troops, and subsequent attempts to challenge the Buyids who seized control of Baghdad and lower Iraq in 945 ended in repeated failure. Twice, his capital Mosul was captured by Buyid forces, which were unable to defeat local opposition to their rule. As a result of his failures to retain power, Nasir al-Dawla declined in influence and prestige. He was eclipsed by the actions of his brother Ali, who established his rule more firmly over Aleppo and northern Syria. After 964, Nasir al-Dawla's eldest son Abu Taghlib exercised de facto rule over his domains, and in 967, Nasir al-Dawla was deposed and imprisoned, dying in captivity a year or two later.

Life

[edit]Origin and family

[edit]

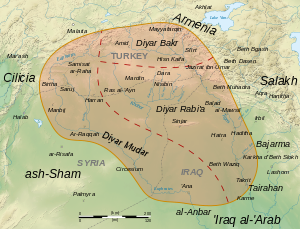

Nasir al-Dawla was born al-Hasan ibn Abdallah, the eldest son of Abu'l-Hayja Abdallah ibn Hamdan (died 929); son of Hamdan ibn Hamdun ibn al-Harith, who gave his name to the Hamdanid dynasty, and a Kurdish Woman.[2][3] The Hamdanids were a branch of the Banu Taghlib, an Arab tribe resident in the area of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) since pre-Islamic times.[4] The Taghlib had traditionally controlled Mosul and its region until the late 9th century, when the Abbasid government tried to impose firmer control over the province. Hamdan ibn Hamdun was one of the Taghlibi leaders most determined in opposing this move. Notably, in his effort to fend off the Abbasids, he secured the alliance of the Kurds living in the mountains north of Mosul, a fact which would be of considerable importance in his family's later fortunes. Family members intermarried with Kurds, who were also prominent in the Hamdanid military.[5][6]

Hamdan's possessions were captured in 895 by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu'tadid (r. 892–902), and Hamdan himself was forced to surrender near Mosul after a long chase. He was put in prison, but his son Husayn ibn Hamdan, who had surrendered the fortress of Ardumusht to the caliph's forces, managed to secure the family's future. He raised troops among the Taghlib in exchange for tax remissions, and established a commanding influence in the Jazira by acting as a mediator between the Abbasid authorities and the Arab and Kurdish population. It was this strong local base which allowed the family to survive its often strained relationship with the central Abbasid government in Baghdad during the early 10th century.[5][7] Husayn was a successful general, distinguishing himself against the Kharijites and the Tulunids, but was disgraced after supporting the failed usurpation of Ibn al-Mu'tazz in 908. His younger brother Ibrahim was governor of Diyar Rabi'a (the province around Nasibin) in 919 and after his death in the next year he was succeeded by another brother, Dawud.[5][8] Hasan's father Abdallah served as emir (governor) of Mosul in 905/6–913/4, was repeatedly disgraced and rehabilitated as the political situation changed in Baghad, until re-assuming control of Mosul in 925/6. Enjoying firm relations with the powerful commander of the caliphal army, Mu'nis al-Khadim, in 929 he played a leading role in the short-lived usurpation of al-Qahir (who would later reign as caliph in 932–934) against al-Muqtadir (r. 908–932), and was killed during its suppression.[9][10] According to the historian Marius Canard, Abdallah established himself as the most prominent member of the first generation of the Hamdanid dynasty, and was essentially the founder of the Hamdanid emirate of Mosul.[11]

Consolidation of control over the Jazira

[edit]

During his absence in Baghdad in his final years from 920/21 on, Abdallah relegated authority over Mosul to Hasan.[12][13] After Abdallah's death, however, al-Muqtadir took the opportunity to avenge himself upon the Hamdanids, and appointed an unrelated governor over Mosul, while Abdallah's domains were divided among his surviving brothers. Faced with the claims of his uncles, Hasan was left in charge of a small portion, on the left bank of the Tigris.[11][13] In 930, after the caliph's governor died,[13] Hasan managed to regain control over Mosul, but his uncles Nasr and Sa'id soon removed him from power and confined him to the western parts of the Diyar Rabi'a. In 934, Hasan again recovered Mosul, but Sa'id, residing in Baghdad and supported by the caliphal government, evicted him again. Hasan fled to Armenia, from where he orchestrated Sa'id's murder. Only then did his troops occupy Mosul and establish him permanently as its ruler.[11] Finally, after defeating caliphal forces under the vizier Ibn Muqla and the Banu Habib, his rivals among the Taghlib, in late 935 the caliph al-Radi was forced to formally recognize him as governor of Mosul and of the entire Jazira, in exchange for an annual tribute of 70,000 gold dinars and supplies of flour for the two caliphal capitals of Baghdad and Samarra.[11][12]

Hasan still had to overcome considerable resistance to his rule outside of his family's core region around Mosul. In Diyar Bakr, the governor of Mayyafariqin, Ali ibn Ja'far, rebelled against Hasan, and in Diyar Mudar, the Qaysi tribes of the region around Saruj also revolted. Hasan subdued them and secured control over the entire Jazira by the end of 936, largely due to the efforts of his brother Ali, who was given the governorship of the two provinces as a reward.[11][14] In the meantime, the defeated Banu Habib, some 10,000 strong and under the leadership of al-Ala ibn al-Mu'ammar, left their lands and fled to territory controlled by the Byzantine Empire. This unprecedented move may be explained by the fact that a significant portion of the tribe still practised Christianity, or by pressure upon their grazing lands by tribes from the south, but the primary goal of the move was to escape from Hamdanid authority and taxation.[12] Hasan also attempted to extend his control to Sajid-ruled Adharbayjan in 934 and 938, but his efforts failed.[13]

Struggle for control of the Caliphate

[edit]

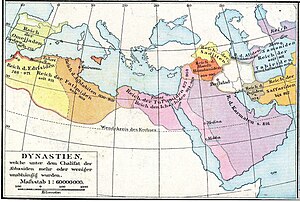

While he tried to consolidate his rule over Mosul, Hasan showed himself conspicuously loyal to the Abbasid regime, and refused to support the revolt of Mu'nis al-Khadim against the caliph al-Muqtadir in 932.[13] Mu'nis succeeded in overthrowing and killing al-Muqtadir, beginning a vicious circle of coups. Over the next few years the Abbasid government all but collapsed, until in 936 the powerful governor of Wasit, Muhammad ibn Ra'iq, assumed the title of amir al-umara ('commander of commanders') and with it de facto control of the Abbasid government. Caliph al-Radi was reduced to a figurehead role, while the extensive civil bureaucracy was cut down dramatically both in size and power.[15] Ibn Ra'iq's position was anything but secure, however, and soon a convoluted struggle for control of his office, and the Caliphate with it, broke out among the various local rulers and the Turkish and Daylamite military chiefs, which ended in 946 with the ultimate victory of the Buyids.[16][17]

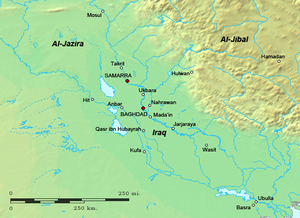

Thus, in the late 930s, Hasan, encouraged by his control over a large and rich domain, entered the intrigues of the Abbasid court, and became one of the main contenders for the title of amir al-umara.[11] At first, Hasan tried to exploit the weakness of the Abbasid government to withhold his payment of tribute, but the Turk Bajkam, who had ousted Ibn Ra'iq in 938, quickly forced him to back down.[13] Hasan then supported Ibn Ra'iq in the latter's quest to regain his lost position. Bajkam tried to forcefully evict Hasan from his Jaziran domains, but in vain, and was eventually killed in a skirmish with Kurdish brigands in early 941.[11][17][18] Hasan's great chance came in early 942, when Caliph al-Muttaqi (r. 940–944) and his closest aides fled Baghdad to escape the city's imminent fall to the Baridis of Basra and sought refuge at Mosul. Hasan now made a direct bid for power: he had Ibn Ra'iq assassinated and succeeded him as amir al-umara, receiving the honorific laqab of Nasir al-Dawla ('Defender of the Dynasty'). He then escorted the caliph back to Baghdad, which they entered on 4 June 942. To secure his position further, Nasir al-Dawla married his daughter to the caliph's son.[11][18][19] Along with their cousin, Husayn ibn Sa'id, Nasir al-Dawla's brother Ali was instrumental in the Hamdanid enterprise, taking the field against the Baridis, who still controlled the rich province of Basra and were determined to regain Baghdad. After scoring a victory over them at the Battle of al-Mada'in, Ali was awarded the laqab of Sayf al-Dawla ('Sword of the Dynasty'), by which he became famous.[11][14][20] This double award marked the first time that a laqab incorporating the prestigious element al-Dawla was granted to anyone other than the vizier, the Caliphate's chief minister, and was a symbolic affirmation of the military's predominance over the civil bureaucracy.[14]

The Hamdanids' success and rule over the Abbasid capital lasted for little more than a year. They lacked funds and were politically isolated, finding little support among the Caliphate's most powerful vassals, the Samanids of Transoxiana and the Ikhshidids of Egypt. Consequently, when in late 943 a mutiny broke out among their troops (mostly composed of Turks, Daylamites, Carmathians and only a few Arabs) over pay issues, under the leadership of the Turkish general Tuzun, they were forced to quit Baghdad and return to their base, Mosul.[11][20][21] Caliph al-Muttaqi now appointed Tuzun as amir al-umara, but the Turk's overbearing manner induced al-Muttaqi to once again seek refuge in the Hamdanid court. The Hamdanid forces under Sayf al-Dawla took the field against Tuzun's army, but were defeated. The Hamdanids now concluded an agreement with Tuzun which allowed them to keep the Jazira and even gave them nominal authority over northern Syria (which at the time was not under Hamdanid control), in exchange for an annual tribute of 3.6 million dirhams.[11][20][21]

In the meantime, the caliph was brought to Raqqa for greater safety, while Husayn ibn Sa'id tried to secure control over northern Syria and pre-empt Egypt's ruler Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid from taking control of the region. The attempt failed, as al-Ikhshid himself advanced into Syria, took Aleppo and marched to Raqqa, where he met the caliph. Al-Ikhshid tried to persuade al-Muttaqi to come to Egypt under his protection, but the caliph refused, and al-Ikhsid returned to Egypt. Instead, al-Muttaqi, persuaded by Tuzun's assurances of loyalty and safety, returned to Baghdad, where Tuzun deposed and blinded him, replacing him with al-Mustakfi (r. 944–946).[16][21][22] At the news of this crime, Nasir al-Dawla again refused payment of tribute, but Tuzun marched against him and forced his compliance.[21] Henceforth, Nasir al-Dawla would be tributary to Baghdad, but he would find it difficult to resign himself to his loss of power over the city he once ruled, and during subsequent years he would undertake several attempts to regain it.[23]

Wars with the Buyids

[edit]

In late 945, Tuzun died. His death weakened the Abbasid government's ability to maintain its independence against the rising power of the Buyids, who under Ahmad ibn Buya had already consolidated control over Fars and Kerman, and secured the cooperation of the Baridis. Al-Mustakfi's secretary, Ibn Shirzad, tried to confront the Buyids by calling upon Nasir al-Dawla's aid, but Ahmad advanced on Baghdad with his troops, and in January 946 he obtained his appointment as amir al-umara with the honorific Mu'izz al-Dawla ('Strengthener of the Dynasty').[21][22][24] To secure their position, the Buyids immediately marched against the Hamdanids. Nasir al-Dawla countered by marching down the eastern bank of the Tigris river and blockading Baghdad. In the end, however, the Buyids defeated the Hamdanids in battle and forced Nasir al-Dawla to retire to Ukbara.[21] From there, Nasir al-Dawla began negotiations, aiming to secure recognition of Hamdanid control over the Jazira, Syria and even Egypt as tributaries of the Caliphate, with the boundary between Buyid and Hamdanid spheres placed at Tikrit. Negotiations were disrupted by a rebellion among the Hamdanids' Turkish troops, but Mu'izz al-Dawla, who for the moment preferred a stable Hamdanid principality to anarchy on his northern border, helped Nasir al-Dawla suppress it. The peace was agreed on terms favourable to the Hamdanids, and was affirmed by one of Nasir al-Dawla's sons being taken as a hostage to Baghdad.[11][21]

Conflict between the two rivals was renewed in 948, when Mu'izz al-Dawla again marched against Mosul, but was forced to cut off his campaign to assist his brother Rukn al-Dawla, who was having trouble in Persia. In exchange, Nasir al-Dawla agreed to recommence the payment of tribute for the Jazira and Syria, as well as to add the names of the three Buyid brothers after that of the caliph in the Friday prayer.[21] Another round of warfare erupted in 956–958. While the Buyids were preoccupied with the rebellion of their Daylamite troops under Rezbahan ibn Vindadh-Khurshid in southern Iraq, Nasir al-Dawla took the opportunity to advance south and capture Baghdad. After the suppression of the Daylamite revolt, however, the Hamdanids were not able to maintain their position in the face of the Buiyd counteroffensive, and abandoned the city.[21][25] Peace was renewed in exchange for the recommencement of tribute and an additional indemnity, but when Nasir al-Dawla refused to send the second year's payment, the Buyid ruler advanced north. Unable to confront the Buyid army in the field, Nasir al-Dawla abandoned Mosul and fled first to Mayyafariqin, and then to his brother Sayf al-Dawla in Aleppo. The Buyids captured Mosul and Nasibin, but the Hamdanids and their supporters withdrew to their home territory in the mountains of the north, taking with them their treasures as well as all government records and tax registers. As a result, the Buyid army was unable to support itself in the conquered territory, all the more since the predominantly Daylamite troops were resented by the local people, who launched guerrilla attacks on them.[21][26] Sayf al-Dawla tried to mediate with Mu'izz al-Dawla, but his first approaches were rebuffed. Only when Sayf al-Dawla agreed to assume the burden of paying his brother's tribute for the entire Diyar Rabi'a did the Buyid ruler agree to peace. This agreement marks the reversal of roles between the two Hamdanid brothers, and the establishment of the predominance of the family's Syrian branch.[21][26]

In 964, Nasir al-Dawla tried to renegotiate the terms of the arrangement, but also to secure Buyid recognition for his eldest son, Fadl Allah Abu Taghlib al-Ghadanfar, as his successor. Mu'izz al-Dawla refused Nasir al-Dawla's demands, and again invaded Hamdanid territory. Once again Mosul and Nasibin were captured, while the Hamdanids fled to the mountain fortresses. As in 958, the Buyids were unable to maintain themselves for long in the Jazira, and soon an agreement was reached which allowed the Hamdanids to return to Mosul. This time, however, Abu Taghlib emerged as the effective leader in his father's place: it was with him, rather than the aged Nasir al-Dawla, that Mui'zz al-Dawla concluded a treaty.[11][21][26] The end of Nasir al-Dawla's rule came in 967, in the same year that saw the deaths of his brother Sayf al-Dawla and his great rival, Mu'izz al-Dawla. Nasir al-Dawla was reportedly so much affected by his brother's death that he lost interest in life and became remote and avaricious.[21] In the end, Abu Taghlib, already the de facto governor of the emirate, deposed him with the aid of his Kurdish mother, Fatima bint Ahmad, who according to Ibn al-Athir exercised considerable influence over her husband's affairs.[21][27] Nasir al-Dawla tried to counter them by turning to one of his other sons by a different mother, Hamdan. In reaction, Abu Taghlib imprisoned him in the fortress of Ardumusht, where he died in 968 or 969.[11][21]

Domestic policies

[edit]Nasir al-Dawla was heavily criticized by contemporaries for his oppressive fiscal policies and the suffering they caused among the population.[21] The traveller Ibn Hawqal, who visited Nasir al-Dawla's domains, reports in length on his seizure of private land in the most fertile regions of the Jazira, on flimsy legal pretexts, until he became the greatest landowner in his province. This was linked with the practice of a monoculture of cereals, destined to feed the growing population of Baghdad, and coupled with heavy taxation, so that Sayf al-Dawla and Nasir al-Dawla are said to have become the wealthiest princes in the Muslim world.[21][28] Nevertheless, the Hamdanid administrative machinery seems to have been fairly rudimentary, and the tribute paid to the Buyids—estimated at somewhere between two and four million dirhams, when it was paid at all—was a heavy burden on the treasury.[20]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Full name and genealogy, according to Ibn Khallikan: Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn Abū'l Ḥayjā ʿAbd Allāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Lūqman ibn Rashīd ibn al-Mathnā ibn Rāfīʿ ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Ghatif ibn Miḥrāba ibn Ḥāritha ibn Mālik ibn ʿUbayd ibn ʿAdī ibn Usāma ibn Mālik ibn Bakr ibn Ḥubayb ibn ʿAmr ibn Ghanm ibn Taghlib.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ Ibn Khallikan 1842, p. 404.

- ^ Canard 1971, pp. 126, 127.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (2015). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Taylor & Francis. p. 232. ISBN 9781317376392.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b c Canard 1971, p. 126.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 266, 269.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 266, 268.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Canard 1971, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Canard 1971, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d e f Bowen 1993, p. 994.

- ^ a b c Bianquis 1997, p. 104.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 192–195.

- ^ a b Bonner 2010, pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Bonner 2010, p. 355.

- ^ Bowen 1993, pp. 994–995.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Bowen 1993, p. 995.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Bonner 2010, p. 356.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 221, 271.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 271.

- ^ El-Azhari 2019, p. 86.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 265.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bianquis, Thierry (1997). "Sayf al-Dawla". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 103–110. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Bonner, Michael (2010). "The waning of empire, 861–945". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–359. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Bowen, H. (1993). "Nāṣir al-Dawla". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 994–995. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- El-Azhari, Taef (2019). Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661-1257. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-2318-2.

- Ibn Khallikan (1842). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Translated from the Arabic. Vol. I. Translated by Baron Mac Guckin de Slane. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 1184199260.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.