Orchestra

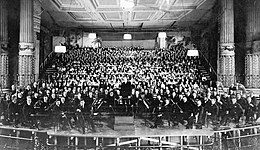

An orchestra (/ˈɔːrk[invalid input: 'ɨ']strə/ or US: /ˈɔːrˌkɛstrə/; Italian: [orˈkɛstra]) is a large instrumental ensemble, often used in classical music, that contains sections of string (violin, viola, cello and double bass), brass, woodwind, and percussion instruments. Other instruments such as the piano and celesta may sometimes be grouped into a fifth section such as a keyboard section or may stand alone, as may the concert harp and, for 20th and 21st century compositions, electric and electronic instruments. The term orchestra derives from the Greek ὀρχήστρα (orchestra), the name for the area in front of an ancient Greek stage reserved for the Greek chorus.[1] The orchestra grew by accretion throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but changed very little in composition during the course of the 20th century.

A smaller-sized orchestra for this time period (of about fifty musicians or fewer) is called a chamber orchestra. A full-size orchestra (about 70-100 musicians) may sometimes be called a symphony orchestra or philharmonic orchestra; these modifiers do not necessarily indicate any strict difference in either the instrumental constitution or role of the orchestra, but can be useful to distinguish different ensembles based in the same city (for instance, the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra). A symphony orchestra will usually have over eighty musicians on its roster, in some cases over a hundred, but the actual number of musicians employed in a particular performance may vary according to the work being played and the size of the venue. A leading chamber orchestra might employ as many as fifty musicians; some are much smaller than that. The term concert orchestra may sometimes be used (e.g., BBC Concert Orchestra; RTÉ Concert Orchestra)—no distinction is made on size of orchestra by use of this term, although their use is generally distinguished as for live concert. As such they are commonly chamber orchestras. There are several types of amateur orchestras, including school orchestras, youth orchestras and community orchestras.

Orchestras are usually led by a conductor who directs the performance by way of visible gestures. The conductor unifies the orchestra, sets the tempo and shapes the sound of the ensemble.[2] Orchestras play a wide range of repertoire, including symphonies, overtures, concertos, and music for operas and ballets.

Instrumentation

The typical symphony orchestra consists of four groups of related musical instruments called the woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings (violin, viola, cello and double bass). Other instruments such as the piano and celesta may sometimes be grouped into a fifth section such as a keyboard section or may stand alone, as may the concert harp and electric and electronic instruments. The orchestra, depending on the size, contains almost all of the standard instruments in each group. In the history of the orchestra, its instrumentation has been expanded over time, often agreed to have been standardized by the classical period[3] and Ludwig van Beethoven's influence on the classical model.[4] In the 20th century, new repertory demands expanded the instrumentation of the orchestra, resulting in a flexible use of the classical-model instruments in various combinations.

Beethoven's influence

The so-called "standard complement" of double winds and brass in the orchestra from the first half of the 19th century is generally attributed to the forces called for by Beethoven.[citation needed] The exceptions to this are his Symphony No. 4, Violin Concerto, and Piano Concerto No. 4, which each specify a single flute. The composer's instrumentation almost always included paired flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets. Beethoven carefully calculated the expansion of this particular timbral "palette" in Symphonies 3, 5, 6, and 9 for an innovative effect. The third horn in the "Eroica" Symphony arrives to provide not only some harmonic flexibility, but also the effect of "choral" brass in the Trio. Piccolo, contrabassoon, and trombones add to the triumphal finale of his Symphony No. 5. A piccolo and a pair of trombones help deliver storm and sunshine in the Sixth. The Ninth asks for a second pair of horns, for reasons similar to the "Eroica" (four horns has since become standard); Beethoven's use of piccolo, contrabassoon, trombones, and untuned percussion—plus chorus and vocal soloists—in his finale, are his earliest suggestion that the timbral boundaries of symphony might be expanded for good. For several decades after his death, symphonic instrumentation was faithful to Beethoven's well-established model, with few exceptions.[citation needed]

Expanded instrumentation

Apart from the core orchestral complement, various other instruments are called for occasionally.[5] These include the classical guitar, heckelphone, flugelhorn, cornet, harpsichord, and organ. Saxophones, for example, appear in some 19th- through 21st-century scores. While appearing only as featured solo instruments in some works, for example Maurice Ravel's orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition and Sergei Rachmaninoff's Symphonic Dances, the saxophone is included in other works, such as Ravel's Boléro, Sergei Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet Suites 1 and 2, Vaughan Williams' Symphonies No.6 and 9 and William Walton's Belshazzar's Feast, and many other works as a member of the orchestral ensemble. The euphonium is featured in a few late Romantic and 20th-century works, usually playing parts marked "tenor tuba", including Gustav Holst's The Planets, and Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben. The Wagner tuba, a modified member of the horn family, appears in Richard Wagner's cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen and several other works by Strauss, Béla Bartók, and others; it has a prominent role in Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 in E Major.[6] Cornets appear in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake, Claude Debussy's La Mer, and several orchestral works by Hector Berlioz. Unless these instruments are played by members doubling on another instrument (for example, a trombone player changing to euphonium for a certain passage), orchestras will use freelance musicians to augment their regular rosters.

The 20th-century orchestra was far more flexible than its predecessors.[7] In Beethoven's and Felix Mendelssohn's time, the orchestra was composed of a fairly standard core of instruments which was very rarely modified. As time progressed, and as the Romantic period saw changes in accepted modification with composers such as Berlioz and Mahler, the 20th century saw that instrumentation could practically be hand-picked by the composer. Today, however, the modern orchestra has generally been considered standardized with the modern instrumentation listed below.

With this history in mind, the orchestra can be seen to have a general evolution as outlined below. The first is a Baroque orchestra, the second is a typical classical orchestra (i.e. Beethoven/Joseph Haydn), the third is typical of an early/mid-Romantic (i.e. Franz Schubert/Hector Berlioz/Robert Schumann), late-Romantic/early 20th century (i.e. Wagner/Brahms/Mahler/Igor Stravinsky), to the common complement of a present-day modern orchestra (i.e. John Adams/Samuel Barber/Aaron Copland/Philip Glass/Krzysztof Penderecki).

Baroque orchestra

Classical orchestra

Early Romantic orchestra

Late Romantic orchestra

Modern orchestra

|

|

Organization

Among the instrument groups and within each group of instruments, there is a generally accepted hierarchy. Every instrumental group (or section) has a principal who is generally responsible for leading the group and playing orchestral solos. The violins are divided into two groups, first violin and second violin, with the second violins playing with lower registers than the first violins. The principal first violin is called the concertmaster (or "leader" in the UK) and is not only considered the leader of the string section, but the second-in-command of the entire orchestra, behind only the conductor. The concertmaster leads the pre-concert tuning and handles musical aspects of orchestra management, such as determining the bowings for the violins or for all of the string section. The concertmaster usually sits to the conductor's left, closest to the audience. In some U.S. and British orchestras, the concertmaster comes on stage after the rest of the orchestra is seated, takes a bow, and receives applause before the conductor (and the soloists, if there are any) appear on stage.[citation needed]

The principal trombone is considered the leader of the low brass section, while the principal trumpet is generally considered the leader of the entire brass section. While the oboe often provides the tuning note for the orchestra (due to 300-year-old convention), no principal is the leader of the woodwind section though in woodwind ensembles, often the flute is leader.[8] Instead, each principal confers with the others as equals in the case of musical differences of opinion. The horn, while technically a brass instrument, often acts in the role of both woodwind and brass.[citation needed] Most sections also have an assistant principal (or co-principal or associate principal), or in the case of the first violins, an assistant concertmaster, who often plays a tutti part in addition to replacing the principal in his or her absence. Principal, co-principal and assistant principal players are paid a higher salary than regular orchestra members playing the same instrument.[citation needed]

A section string player plays in unison with the rest of the section, except in the case of divided (divisi) parts, where upper and lower parts in the music are often assigned to "outside" (nearer the audience) and "inside" seated players. Where a solo part is called for in a string section, the section leader invariably plays that part. The section leader (or principal) of a string section is also responsible for determining the bowings, often based on the bowings set out by the concertmaster. In some cases, the principal of a string section may use a slightly different bowing than the concertmaster, to accommodate the requirements of playing their instrument (e.g., the double-bass section). Principals of a string section will also lead entrances for their section, typically by lifting the bow before the entrance, to ensure the section plays together. Tutti wind and brass players generally play a unique but non-solo part. Section percussionists play parts assigned to them by the principal percussionist.

In modern times, the musicians are usually directed by a conductor, although early orchestras did not have one, giving this role instead to the concertmaster or the harpsichordist playing the continuo. Some modern orchestras also do without conductors, particularly smaller orchestras and those specializing in historically accurate (so-called "period") performances of baroque and earlier music.

The most frequently performed repertoire for a symphony orchestra is Western classical music or opera. However, orchestras are used sometimes in popular music (e.g., to accompany a rock or pop band in a concert), extensively in film music, and increasingly often in video game music. Orchestras are also used in the symphonic metal genre. The term "orchestra" can also be applied to a jazz ensemble, for example in the performance of big-band music.

Selection and appointment of members

All members of a professional orchestra must audition for positions in the ensemble. Performers typically play one or more solo pieces of the auditionee's choice, such as a movement of a concerto, and a variety of excerpts from the orchestral literature that are advertised in the audition poster (so the auditionees can prepare). The excerpts are typically the most technically challenging parts and solos from the orchestral literature. Orchestral auditions are typically held in front of a panel that includes the conductor, the concertmaster, the principal player of the section for which the auditionee is applying and possibly other principal players and regular orchestra members.

The most promising candidates from the first round of auditions are invited to return for a second or third round of auditions, which allows the conductor and the panel to compare the best candidates. Performers may be asked to sight read orchestral music. The final stage of the audition process in some orchestras is a test week, in which the performer plays with the orchestra for a week or two, which allows the conductor and principal players to see if the individual can function well in an actual rehearsal and performance setting.

There are a range of different employment arrangements. The most sought-after positions are permanent, tenured positions in the orchestra. Orchestras also hire musicians on contracts, ranging in length from a single concert to a full season or more. Contract performers may be hired for individual concerts when the orchestra is doing an exceptionally large late-Romantic era orchestral work, or to substitute for a permanent member who is sick. A professional musician who is hired to perform for a single concert is sometimes called a "sub". Some contract musicians may be hired to replace permanent members for the period that the permanent member is on parental leave or disability leave.

Working conditions and concert preparation

Orchestral musicians typically sit to rehearse and play, although some musicians such as percussionists and double bassists may stand. Musicians rehearse under the direction of the conductor for several rehearsals. For particularly challenging pieces, sectional rehearsals may be held (e.g., the viola section or the brass section). In addition to the preparation that takes place during rehearsals, orchestral musicians are expected to prepare their individual parts by practicing them. Some rehearsals are held in large rehearsal halls or rooms. The final rehearsal, called the dress rehearsal, is held on the stage where the orchestra is performing, so that the conductor can hear the balance of instrument sections and the sound in the performance hall.[citation needed]

The concerts are typically held on a stage in a large auditorium in an arts centre or opera house, although orchestras may also play in churches or outdoor stages. Once a conductor and orchestra have prepared a symphony program in rehearsal, the program may be played once, twice, or for a larger number of performances. The latter approach is typically used during a concert tour or for an extended run of an opera or other presentation. During tours, musicians have to travel, stay in hotels and adapt to changing performance venues. During performances, orchestra members typically wear formal evening wear, such as black tuxedos for men and black evening gowns or pantsuits for women.[citation needed]

In the US and Canada, many professional orchestral musicians are members are members of a union, the American Federation of Musicians. Unions negotiate working conditions such as the length of rehearsals and breaks and overtime pay. In each orchestra, an orchestra member serves as a union steward, to ensure that the conditions of work are respected. Union stewards may also sit in during auditions, to ensure the fairness of the process.[citation needed]

Gender of ensembles

Historically, major professional orchestras have been mostly or entirely composed of male musicians. The first women members hired in professional orchestras have been harpists. The Vienna Philharmonic, for example, did not accept women to permanent membership until 1997, far later than comparable orchestras (the other orchestras ranked among the world’s top five by Gramophone in 2008).[9] The last major orchestra to appoint a woman to a permanent position was the Berlin Philharmonic.[10] In February 1996, the Vienna Philharmonic's principal flute, Dieter Flury, told Westdeutscher Rundfunk that accepting women would be "gambling with the emotional unity (emotionelle Geschlossenheit) that this organism currently has".[11] In April 1996, the orchestra’s press secretary wrote that "compensating for the expected leaves of absence" of maternity leave would be a problem.[12]

In 1997, the Vienna Philharmonic was "facing protests during a [US] tour" by the National Organization for Women and the International Alliance for Women in Music. Finally, "after being held up to increasing ridicule even in socially conservative Austria, members of the orchestra gathered [on 28 February 1997] in an extraordinary meeting on the eve of their departure and agreed to admit a woman, Anna Lelkes, as harpist."[13] As of 2013, the orchestra has six female members; one of them, violinist Albena Danailova became one of the orchestra’s concertmasters in 2008, the first woman to hold that position.[14] In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the orchestra's membership. VPO president Clemens Hellsberg said the VPO now uses completely screened blind auditions.[15]

In 2013, an article in Mother Jones stated that while "[m]any prestigious orchestras have significant female membership—women outnumber men in the New York Philharmonic's violin section—and several renowned ensembles, including the National Symphony Orchestra, the Detroit Symphony, and the Minnesota Symphony, are led by women violinists", the double bass, brass, and percussion sections of major orchestras "...are still predominantly male."[16] A 2014 BBC article stated that the "...introduction of ‘blind’ auditions, where a prospective instrumentalist performs behind a screen so that the judging panel can exercise no gender or racial prejudice, has seen the gender balance of traditionally male-dominated symphony orchestras gradually shift."[17]

Amateur ensembles

There are also a variety of amateur orchestras:

- School orchestras: These orchestras consist of students from an elementary or secondary school. They may be students from a music class or program or they may be drawn from the entire school body. School orchestras are typically led by a music teacher.

- University or conservatory orchestras: These orchestras consist of students from a university or music conservatory. In some cases, university orchestras are open to all students from a university, from all programs. Larger universities may have two university orchestras: one made up of music majors and a second orchestra open to university students from all academic programs. University and conservatory orchestras are typically led by a conductor who is a Professor at the university or conservatoire.

- Youth orchestras: These orchestras consist of teens and young adults drawn from an entire city or region. In some cases, youth orchestras may consist of teens or young adults from an entire country (e.g., Canada's National Youth Orchestra).

- Community orchestras: These orchestras consist of amateur performers drawn from an entire region or city. Community orchestras typically consist mainly of adult amateur musicians. Community orchestras range in level from intermediate-level ensembles to fairly advanced amateur groups. In some cases, university or conservatory students may also be members of community orchestras. While community orchestra members are mostly amateurs, in some orchestras, a small number of professionals may be hired to act as principal players and section leaders.

Repertoire

Orchestras play a wide range of repertoire ranging from 17th-century dance suites to 21st-century symphonies. Orchestras have become synonymous with the symphony, an extended musical composition in Western classical music that typically contains multiple movements. Symphonies are notated in a musical score, which contains all the instrument parts. The conductor uses the score to study the symphony before rehearsals and decide on their interpretation (e.g., tempos, articulation, phrasing, etc.), and to follow the music during rehearsals and concerts. Orchestral musicians play from parts which contain just the notated music for their instrument. A small number of symphonies also contain vocal parts (e.g., Beethoven's Ninth Symphony).

Orchestras also perform overtures, a term originally applied to the instrumental introduction to an opera.[18] During the early Romantic era, composers such as Beethoven and Mendelssohn began to use the term to refer to independent, self-existing instrumental, programmatic works that presaged genres such as the symphonic poem, a form devised by Franz Liszt in several works that began as dramatic overtures. These were "at first undoubtedly intended to be played at the head of a programme".[18] In the 1850s the concert overture began to be supplanted by the symphonic poem.

Orchestras also play with instrumental soloists in concertos. During concertos, the orchestra plays an accompaniment role to the soloist (e.g., a solo violinist or pianist) and, at times, introduces musical themes or interludes while the soloist is not playing. Orchestras also play during operas, ballets, some musical theatre works and some choral works (both sacred works such as Masses and secular works). In operas and ballets, the orchestra accompanies the singers and dancers, respectively, and plays overtures and interludes where the melodies played by the orchestra take centre stage. The orchestral repertoire also includes a range of other pieces, such as Baroque dance suites, symphonic dances and suites of film music.

History

Mannheim school

This change, from civic music making where the composer had some degree of time or control, to smaller court music making and one-off performance, placed a premium on music that was easy to learn, often with little or no rehearsal. The results were changes in musical style and emphasis on new techniques. Mannheim had one of the most famous orchestras of that time, where notated dynamics and phrasing, previously quite rare, became standard (see Mannheim school). It also attended a change in musical style from the complex counterpoint of the baroque period, to an emphasis on clear melody, homophonic textures, short phrases, and frequent cadences: a style that would later be defined as classical.

Throughout the late 18th century composers would continue to have to assemble musicians for a performance, often called an "Academy", which would, naturally, feature their own compositions. In 1781, however, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra was organized from the merchants concert society, and it began a trend towards the formation of civic orchestras that would accelerate into the 19th century. In 1815, Boston's Handel and Haydn Society was founded, in 1842 the New York Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic were formed, and in 1858, the Hallé Orchestra was formed in Manchester. There had long been standing bodies of musicians around operas, but not for concert music: this situation changed in the early 19th century as part of the increasing emphasis in the composition of symphonies and other purely instrumental forms. This was encouraged by composer critics such as E. T. A. Hoffmann who declared that instrumental music was the "purest form" of music. The creation of standing orchestras also resulted in a professional framework where musicians could rehearse and perform the same works repeatedly, leading to the concept of a repertoire in instrumental music.

Performance standards

In the 1830s, conductor François Antoine Habeneck began rehearsing a selected group of musicians in order to perform the symphonies of Beethoven, which had not been heard in their entirety in Paris. He developed techniques of rehearsing the strings separately, notating specifics of performance, and other techniques of cuing entrances that were spread across Europe. His rival and friend Hector Berlioz would adopt many of these innovations in his touring of Europe.

Instrumental craftsmanship

The invention of the piston and rotary valve by Heinrich Stölzel and Friedrich Blühmel, both Silesians, in 1815, was the first in a series of innovations, including the development of modern keywork for the flute by Theobald Boehm and the innovations of Adolphe Sax in the woodwinds. These advances would lead Hector Berlioz to write a landmark book on instrumentation, which was the first systematic treatise on the use of instrumental sound as an expressive element of music.[19]

The effect of the invention of valves for the brass was felt almost immediately: instrument-makers throughout Europe strove together to foster the use of these newly refined instruments and continuing their perfection; and the orchestra was before long enriched by a new family of valved instruments, variously known as tubas, or euphoniums and bombardons, having a chromatic scale and a full sonorous tone of great beauty and immense volume, forming a magnificent bass. This also made possible a more uniform playing of notes or intonation, which would lead to a more and more "smooth" orchestral sound that would peak in the 1950s with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra and the conducting of Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic.[citation needed]

During this transition period, which gradually eased the performance of more demanding "natural" brass writing, many composers (notably Wagner and Berlioz) still notated brass parts for the older "natural" instruments. This practice made it possible for players still using natural horns, for instance, to perform from the same parts as those now playing valved instruments. However, over time, use of the valved instruments became standard, indeed universal, until the revival of older instruments in the contemporary movement towards authentic performance (sometimes known as "historically informed performance").[citation needed]

At the time of the invention of the valved brass, the pit orchestra of most operetta composers seems to have been modest. An example is Sullivan's use of two flutes, one oboe, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, two cornets (a piston), two trombones, drums and strings.[citation needed]

During this time of invention, winds and brass were expanded, and had an increasingly easy time playing in tune with each other: particularly the ability for composers to score for large masses of wind and brass that previously had been impractical. Works such as the Requiem of Hector Berlioz would have been impossible to perform just a few decades earlier, with its demanding writing for twenty woodwinds, as well as four gigantic brass ensembles each including around four trumpets, four trombones, and two tubas.[citation needed]

Wagner's influence

The next major expansion of symphonic practice came from Richard Wagner's Bayreuth orchestra, founded to accompany his musical dramas. Wagner's works for the stage were scored with unprecedented scope and complexity: indeed, his score to Das Rheingold calls for six harps. Thus, Wagner envisioned an ever-more-demanding role for the conductor of the theatre orchestra, as he elaborated in his influential work On Conducting.[20] This brought about a revolution in orchestral composition, and set the style for orchestral performance for the next eighty years. Wagner's theories re-examined the importance of tempo, dynamics, bowing of string instruments and the role of principals in the orchestra. Conductors who studied his methods would go on to be influential themselves.[vague]

20th century orchestra

As the early 20th century dawned, symphony orchestras were larger, better funded, and better trained than ever before; consequently, composers could compose larger and more ambitious works. The influence of Gustav Mahler was particularly innovational; in his later symphonies, such as the mammoth Symphony No. 8, Mahler pushes the furthest boundaries of orchestral size, employing huge forces. By the late Romantic era, orchestras could support the most enormous forms of symphonic expression, with huge string sections, massive brass sections and an expanded range of percussion instruments. With the recording era beginning, the standards of performance were pushed to a new level, because a recorded symphony could be listened to closely and even minor errors in intonation or ensemble, which might not be noticeable in a live performance, could be heard by critics. As recording technologies improved over the 20th and 21st centuries, eventually small errors in a recording could be "fixed" by audio editing or overdubbing. Some older conductors and composers could remember a time when simply "getting through" the music as best as possible was the standard. Combined with the wider audience made possible by recording, this led to a renewed focus on particular star conductors and on a high standard of orchestral execution.[21] After sound was added to silent film, the lush sound of a full orchestra became a key component of popular film scores.[citation needed]

Counter-revolution

In the 1920s and 1930s, economic as well as artistic considerations led to the formation of smaller concert societies, particularly those dedicated to the performance of music of the avant-garde, including Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg. This tendency to start festival orchestras or dedicated groups would also be pursued in the creation of summer musical festivals, and orchestras for the performance of smaller works. Among the most influential of these was the Academy of St Martin in the Fields under the baton of Sir Neville Marriner.[citation needed]

With the advent of the early music movement, smaller orchestras where players worked on execution of works in styles derived from the study of older treatises on playing became common. These include the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, the London Classical Players under the direction of Sir Roger Norrington and the Academy of Ancient Music under Christopher Hogwood, among others.

Recent trends in the United States

In the United States, the late 20th century saw a crisis of funding and support for orchestras. The size and cost of a symphony orchestra, compared to the size of the base of supporters, became an issue that struck at the core of the institution. Few orchestras could fill auditoriums, and the time-honored season-subscription system became increasingly anachronistic, as more and more listeners would buy tickets on an ad hoc basis for individual events. Orchestral endowments and—more centrally to the daily operation of American orchestras—orchestral donors have seen investment portfolios shrink or produce lower yields, reducing the ability of donors to contribute; further, there has been a trend toward donors finding other social causes more compelling. Also, while government funding is less central to American than European orchestras, cuts in such funding are still significant for American ensembles. Finally, the drastic falling-off of revenues from recording, tied to no small extent to changes in the recording industry itself, began a period of change that has yet to reach its conclusion.

U.S. orchestras that have gone into Chapter 11 bankruptcy include the Philadelphia Orchestra (in April 2011), and the Louisville Orchestra, in December 2010; orchestras that have gone into Chapter 7 bankruptcy and have ceased operations include the Northwest Chamber Orchestra in 2006, the Honolulu Orchestra in March 2011, the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra in April 2011, and the Syracuse Symphony in June 2011. The Festival of Orchestras in Orlando, Florida ceased operations at the end of March, 2011.

One source of financial difficulties that received notice and criticism was high salaries for music directors of US orchestras,[22] which led several high-profile conductors to take pay cuts in recent years.[23][24][25] Music administrators such as Michael Tilson Thomas and Esa-Pekka Salonen argued that new music, new means of presenting it, and a renewed relationship with the community could revitalize the symphony orchestra. The American critic Greg Sandow has argued in detail that orchestras must revise their approach to music, performance, the concert experience, marketing, public relations, community involvement, and presentation to bring them in line with the expectations of 21st-century audiences immersed in popular culture.

It is not uncommon for contemporary composers to use unconventional instruments, including various synthesizers, to achieve desired effects. Many, however, find more conventional orchestral configuration to provide better possibilities for color and depth. Composers like John Adams often employ Romantic-size orchestras, as in Adams' opera Nixon in China; Philip Glass and others may be more free, yet still identify size-boundaries. Glass in particular has recently turned to conventional orchestras in works like the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra and the Violin Concerto No. 2.

Along with a decrease in funding, some U.S. orchestras have reduced their overall personnel, as well as the number of players appearing in performances. The reduced numbers in performance are usually confined to the string section, since the numbers here have traditionally been flexible (as multiple players typically play from the same part).

Conductorless orchestras

The post-revolutionary symphony orchestra Persimfans was formed in the Soviet Union in 1922. The unusual aspect of the orchestra was that, believing that in the ideal Marxist state all people are equal, its members felt that there was no need to be led by the dictatorial baton of a conductor; instead they were led by a committee. Although it was a partial success, the principal difficulty with the concept was in changing tempo. The orchestra survived for ten years before Stalin's cultural politics effectively forced it into disbandment by draining away its funding.[26]

Some ensembles, such as the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, based in New York City, have had more success, although decisions are likely to be deferred to some sense of leadership within the ensemble (for example, the principal wind and string players). Others have returned to the tradition of a principal player, usually a violinist, being the artistic director and running rehearsals (such as the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Amsterdam Sinfonietta & Candida Thompson and the New Century Chamber Orchestra).

Multiple conductors

The techniques of polystylism and polytempo[27] music have recently led a few composers to write music where multiple orchestras perform simultaneously. These trends have brought about the phenomenon of polyconductor music, wherein separate sub-conductors conduct each group of musicians. Usually, one principal conductor conducts the sub-conductors, thereby shaping the overall performance. Some pieces are enormously complex in this regard, such as Evgeni Kostitsyn's Third Symphony, which calls for nine conductors.[citation needed]

For pieces involving offstage members of the orchestra, sometimes a sub-conductor will be stationed offstage with a clear view of the principal conductor. Examples include the ending of "Neptune" from Gustav Holst's The Planets and Percy Grainger's "The Warriors" which includes three conductors: the primary conductor of the orchestra, a secondary conductor directing an off-stage brass ensemble, and a tertiary conductor directing percussion and harp.

Charles Ives often used two conductors, one for example to simulate a marching band coming through his piece. Realizations for Symphonic Band includes one example from Ives. Benjamin Britten's War Requiem is also an important example of the repertoire for more than one conductor.[citation needed]

One of the best examples in the late century orchestral music is Karlheinz Stockhausen's Gruppen, for three orchestras placed around the audience. This way, the sound masses could be spacialized, as in an electroacoustic work. Gruppen was premiered in Cologne, in 1958, conducted by Stockhausen, Bruno Maderna and Pierre Boulez. Recently,[when?] it was performed by Simon Rattle, John Carewe and Daniel Harding.

Other meanings of orchestra

In Ancient Greece, the orchestra was the space between the auditorium and the proscenium (or stage), in which were stationed the chorus and the instrumentalists. The word orchestra literally means "a dancing place".[citation needed]

In some theatres, the orchestra is the area of seats directly in front of the stage (called primafila or platea); the term more properly applies to the place in a theatre, or concert hall reserved for the musicians.[citation needed]

In musical theatre, the accompaniment ensemble for the musical may be called an orchestra (more specifically a pit orchestra), even if it is composed–as been the case since the development of 1960s-era rock musicals–of a small chamber group of eight to twenty or more musicians, including strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion and rock instruments such as electric guitar, electric bass and synthesizer.[citation needed]

See also

- Classical music

- List of symphony orchestra concert halls

- List of symphony orchestras

- List of youth orchestras in the United States

- Orchestral enhancement

- Orchestration

- Radio orchestra

- Shorthand for orchestra instrumentation

- Conductorless orchestra

- String orchestra

- Concert band

- Jazz ensemble

- Rhythm section

- World music

- Film score

Notes and references

- ^ ὀρχήστρα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Conducting". Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music (Fifth ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2007. ISBN 9780199203833.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Jack Westrup, "Instrumentation and Orchestration: 3. 1750 to 1800", New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., edited by Stanley Sadie (New York: Grove, 2001).

- ^ D. Kern Holoman, "Instrumentation and Orchestration: 4. 19th Century", in ibid.

- ^ G.W. Hopkins and Paul Griffiths, "Instrumentation and Orchestration: 5. Impression and Later Developments", in ibid.

- ^ "The Wagner Tuba". The Wagner Tuba. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ G.W. Hopkins and Paul Griffiths, op. cit.

- ^ "An Investigation of Members' Roles in Wind Quintets". Pom.sagepub.com. 2003-01-01. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ "The world's greatest orchestras". gramophone.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ^ James R. Oestreich, "Berlin in Lights: The Woman Question", Arts Beat, The New York Times, 16 November 2007

- ^ Westdeutscher Rundfunk Radio 5, "Musikalische Misogynie", 13 February 1996, transcribed by Regina Himmelbauer; translation by William Osborne

- ^ "The Vienna Philharmonic's Letter of Response to the Gen-Mus List". Osborne-conant.org. 1996-02-25. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Jane Perlez, "Vienna Philharmonic Lets Women Join in Harmony”, The New York Times, February 28, 1997

- ^ Vienna opera appoints first ever female concertmaster, France 24

- ^ James R. Oestrich, "Even Legends Adjust To Time and Trend, Even the Vienna Philharmonic", The New York Times, 28 February 1998

- ^ Hannah Levintova. "Here's Why You Seldom See Women Leading a Symphony". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ Burton, Clemency (2014-10-21). "Culture - Why aren't there more women conductors?". BBC. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ a b Blom 1954.

- ^ Hector Berlioz. Traite d'instrumentation et d'orchestration (Paris: Lemoine, 1843).

- ^ Richard Wagner. On Conducting (Ueber das Dirigiren), a treatise on style in the execution of classical music (London: W. Reeves, 1887).

- ^ See Lance W. Brunner. (1986). "The Orchestra and Recorded Sound", pp 479-532 in Joan Peyser Ed. The Orchestra: Origins and Transformations, New York: Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Michael Cooper (2015-06-13). "Ronald Wilford, Manager of Legendary Maestros, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ Zachary Lewis (2009-03-24). "Cleveland Orchestra plans 'deep' cuts; Welser-Most takes pay cut". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ Donna Perlmutter (2011-08-21). "He conducts himself well through crises". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ Graydon Royce (2014-05-09). "Osmo Vänskä hires on to rebuild Minnesota Orchestra". Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- ^ John Eckhard, "Orchester ohne Dirigent", Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik 158, no. 2 (1997): 40–43.

- ^ "Polytempo Music Articles". Greschak.com. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

Bibliography

- Raynor, Henry (1978). The Orchestra: a history. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-15535-4.

- Sptizer, John, and Neil Zaslaw (2004). The Birth of the Orchestra: History of an Institution, 1650-1815. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816434-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The Orchestra: A User's Manual—A fairly concise overview, including detailed video interviews with players of each instrument and various resources

- Greg Sandow on the Future of Classical Music, Artsjournal.com blog, 25 September 2011

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.