Papier-mâché

Papier-mâché (UK: /ˌpæpieɪ ˈmæʃeɪ/, US: /ˌpeɪpər məˈʃeɪ/; French: [papje mɑʃe], literally "chewed paper", "pulped paper", or "mashed paper") is a composite material consisting of paper pieces or pulp, sometimes reinforced with textiles, bound with an adhesive, such as glue, starch, or wallpaper paste.

Preparation methods

Two main methods are used to prepare papier-mâché. The first method makes use of paper strips glued together with adhesive, and the other uses paper pulp obtained by soaking or boiling paper to which glue is then added.

With the first method, a form for support is needed on which to glue the paper strips. With the second method, it is possible to shape the pulp directly inside the desired form. In both methods, reinforcements with wire, chicken wire, lightweight shapes, balloons or textiles may be needed.

The traditional method of making papier-mâché adhesive is to use a mixture of water and flour or other starch, mixed to the consistency of heavy cream. Other adhesives can be used if thinned to a similar texture, such as polyvinyl acetate-based glues (wood glue or, in the United States, white Elmer's glue). Adding oil of cloves or other additives such as salt to the mixture reduces the chances of the product developing mold.

For the paper strips method, the paper is cut or torn into strips, and soaked in the paste until saturated. The saturated pieces are then placed onto the surface and allowed to dry slowly. The strips may be placed on an armature, or skeleton, often of wire mesh over a structural frame, or they can be placed on an object to create a cast. Oil or grease can be used as a release agent if needed. Once dried, the resulting material can be cut, sanded and/or painted, and waterproofed by painting with a suitable water-repelling paint.[1] Before painting any product of papier-mâché, the glue must be fully dried, otherwise mold will form and the product will rot from the inside out.

For the pulp method, the paper is left in water at least overnight to soak, or boiled in abundant water until the paper dissolves in a pulp. The excess water is drained, an adhesive is added and the papier-mâché applied to a form or, especially for smaller or simpler objects, sculpted to shape.

History

Imperial China

The Chinese under the ruling of the Han dynasty appeared to first use papier-mâché around 200 B.C., not long after they learned how to make paper. They employed the technique to make items such as warrior helmets, mirror cases, snuff boxes, or ceremonial masks.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, coffins and death masks were often made from cartonnage—layers of papyrus or linen covered with plaster.

Middle and Far East

In Persia, papier-mâché has been used to manufacture small painted boxes, trays, étagères and cases. Japan and China also produced laminated paper articles using papier-mâché. In Japan and India, papier-mâché was used to add decorative elements to armor and shields.[2]

Kashmir

In Kashmir as in Persia, papier-mâché has been used to manufacture small painted boxes, bowls lined with metals, trays, étagères and cases. It remains highly marketed in India and is a part of the luxury ornamental handicraft market.[2]

Europe

Starting around 1725 in Europe, gilded papier-mâché began to appear as a low-cost alternative to similarly treated plaster or carved wood in architecture. Henry Clay of Birmingham, England, patented a process for treating laminated sheets of paper with linseed oil to produce waterproof panels in 1772. These sheets were used for building coach door panels as well as other structural uses. Theodore Jennens patented a process in 1847 for steaming and pressing these laminated sheets into various shapes, which were then used to manufacture trays, chair backs, and structural panels, usually laid over a wood or metal armature for strength. The papier-mâché was smoothed and lacquered, or finished with a pearl shell finish. The industry lasted through the 19th century.[3] Russia had a thriving industry in ornamental papier-mâché. A large assortment of painted Russian papier-mâché items appear in a Tiffany & Co. catalog from 1893.[4] Martin Travers the English ecclesiastical designer made much use of papier-mâché for his church furnishings in the 1930s.

Papier-mâché has been used for doll heads starting as early as 1540, molded in two parts from a mixture of paper pulp, clay, and plaster, and then glued together, with the head then smoothed, painted and varnished.[5]

Mexico

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculptures are a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton piedra" (rock cardboard) for the rigidness of the final product.[1] These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. There is also a significant market for collectors as well. Papier-mâché was introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, originally to make items for church. Since then, the craft has developed, especially in central Mexico. In the 20th century, the creation of works by Mexico City artisans Pedro Linares and Carmen Caballo Sevilla were recognized as works of art with patrons such as Diego Rivera. The craft has become less popular with more recent generations, but various government and cultural institutions work to preserve it.

Paper boats

One common item made in the 19th century in America was the paper canoe, most famously made by Waters & Sons of Troy, New York. The invention of the continuous sheet paper machine allows paper sheets to be made of any length, and this made an ideal material for building a seamless boat hull. The paper of the time was significantly stretchier than modern paper, especially when damp, and this was used to good effect in the manufacture of paper boats. A layer of thick, dampened paper was placed over a hull mold and tacked down at the edges. A layer of glue was added, allowed to dry, and sanded down. Additional layers of paper and glue could be added to achieve the desired thickness, and cloth could be added as well to provide additional strength and stiffness. The final product was trimmed, reinforced with wooden strips at the keel and gunwales to provide stiffness, and waterproofed. Paper racing shells were highly competitive during the late 19th century. Few examples of paper boats survived. One of the best known paper boats was the canoe, the "Maria Theresa", used by Nathaniel Holmes Bishop to travel from New York to Florida in 1874–75. An account of his travels was published in the book Voyage of the Paper Canoe.[6][7]

Paper masks

Creating papier-mâché masks is common among elementary school children and craft lovers. Either one's own face or a balloon can be used as a mold. This is common during Halloween time as a facial mask complements the costume.[8]

Paper observatory domes

Papier-mâché panels were used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to produce lightweight domes, used primarily for observatories. The domes were constructed over a wooden or iron framework, and the first ones were made by the same manufacturer that made the early paper boats, Waters & Sons. The domes used in observatories had to be light in weight so that they could easily be rotated to position the telescope opening in any direction, and large enough so that it could cover the large refractor telescopes in use at the time.[9][10][11]

Paper sabots

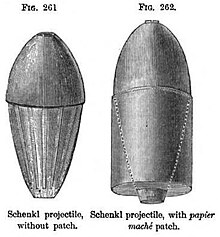

Papier-mâché was used in a number of firearms as a material to form sabots. Despite the extremely high pressures and temperatures in the bore of a firearm, papier-mâché proved strong enough to contain the pressure, and push a sub-caliber projectile out of the barrel with a high degree of accuracy. Papier-mâché sabots were used in everything from small arms, such as the Dreyse needle gun, up to artillery, such as the Schenkl projectile.[12][13]

Modern use

With modern plastics and composites taking over the decorative and structural roles that papier-mâché played in the past, papier-mâché has become less of a commercial product. There are exceptions, such as Micarta, a modern paper composite, and traditional applications such as the piñata. It is still used in cases where the ease of construction and low cost are important, such as in arts and crafts.

Carnival floats

Papier-mâché is commonly used for large, temporary sculptures such as Carnival floats. A basic structure of wood, metal and metal wire mesh, such as poultry netting, is covered in papier-mâché. Once dried, details are added. The papier-mâché is then sanded and painted. Carnival floats can be very large and comprise a number of characters, props and scenic elements, all organized around a chosen theme. They can also accommodate several dozen people, including the operators of the mechanisms. The floats can have movable parts, like the facial features of a character, or its limbs. It is not unusual for local professional architects, engineers, painters, sculptors and ceramists to take part in the design and construction of the floats. New Orleans Mardi Gras float maker Blaine Kern, operator of the Mardi Gras World float museum, brings Carnival float artists from Italy to work on his floats.[14][15]

Theatrical use

Papier-mâché is an economic building material for both sets and costume elements.[1][16] It is also employed in puppetry.

War-time uses

Military drop tanks

During World War II, military aircraft fuel tanks were constructed out of plastic-impregnated paper and used to extend the range or loiter time of aircraft. These tanks were plumbed to the regular fuel system via detachable fittings and dropped from the aircraft when the fuel was expended, allowing short-range aircraft such as fighters to accompany long-range aircraft such as bombers on longer missions as protection forces. Two types of paper tanks were used, a 200-gallon (758 l) conformal fuel tank made by the United States for the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and a 108-gallon (409 l) cylindrical drop tank made by the British and used by the P-47 and the North American P-51 Mustang.[17][18]

Combat decoy

From about 1915 in World War I, the British were beginning to counter the highly effective sniping of the Germans. Among the techniques the British developed, was to employ papier-mâché figures resembling soldiers to draw sniper fire. Some were equipped with an apparatus that produced smoke from a cigarette, to increase the realism of the effect. Bullet holes in the decoys were used to determine the position of enemy snipers who had fired the shots. Very high success rates were claimed for this expedient.[19]

See also

- Vycinanka (belarusian, ukrainian, polish paper art)

- Russian lacquer art

- Decoupage

- Japanning

- Hanji (Korean paper art)

- Papier-mâché binding, a form of binding a book used in the 19th century

- Papier-mâché Tiara, a papal tiara made in exile for Pope Pius VII's papal coronation in a church in Venice in 1800

- Wet-folding, an origami technique that uses damp paper.

Notes

- ^ a b c Haley, Gail E (2002). Costumes for Plays and Playing. Parkway Publishers. ISBN 1-887905-62-6.

- ^ a b Egerton, Wilbraham (1896). A Description of Indian and Oriental Armour. WH Allen & Co.

- ^ Rivers, Shayne; Umney, Nick (2003). Conservation of Furniture. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 205–6. ISBN 0-7506-0958-3.

- ^ Blue Book. Tiffany & Co. 1893.

- ^ Andrews, Deborah ‘Debbie’. "History of Papier Mâché Dolls".

- ^ A history of paper boats, Cupery.

- ^ Bishop, Nathaniel Holmes, Voyage of the Paper Canoe, Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "How to Make Paper Mache Masks", Family crafts, About.

- ^ "Paper observatory domes". Cupery.

- ^ "Columbia's New Observatory" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1884.

- ^ "The special feature of the new observatory at Columbia College will be a paper dome". The Harvard Crimson. March 19, 1883. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Holley, Alexander Lyman (1865), A Treatise on Ordnance and Armor, Trübner & Co

- ^ Spon, Edward; Byrne, Oliver (1872), Spon's Dictionary of Engineering, E&FN

- ^ Barghetti, Adriano (2007). 1994–2003: 130 anni di storia del Carnevale di Viareggio, Carnevale d’Italia e d’Europa (in Italian). Pezzini.

- ^ Abrahams, Roger D (2006). Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras And America's Creole Soul. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3959-8.

- ^ Bendick, Jeanne (1945). Making the Movies. Whittlesey House: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Freeman, Roger Anthony (1970). The Mighty Eighth: Units, Men, and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force). Doubleday.

- ^ Grant, William Newby (1980). P-51 Mustang. Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0-89009-320-7.

- ^ H. Hesketh-Pritchard, "Sniping in France", page 46+, pub: E P Dutton. [1]