Pashalik of Yanina

| Pashalik of Yanina | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-autonomous domain of the Ottoman Empire | |||||||||

| 1788–1822 | |||||||||

| Capital | Ioannina | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| Pasha | |||||||||

• 1787–1822 | Ali Pasha | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1788 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1822 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Pashalik of Yanina or Janina (1788–1822) was a subdivision[2] of the Ottoman Empire centred on the region of Epirus and had a high degree of autonomy in the early 19th century under Ali Pasha, although it was never recognized as such by the Ottoman empire.[2] Its core was the Ioannina Eyalet, centred on the city of Ioannina in southern Epirus, but at its peak it comprised most of Albania and the western portions of Thessaly and Greek Macedonia in Northern Greece.

History

In 1787 Ali Pasha was awarded the pashaluk of Trikala in reward for his support for the sultan's war against Austria. This was not enough to satisfy his ambitions; shortly afterwards, in 1788, he seized control of Ioánnina, which remained his power base for the next 33 years.[citation needed] Like other semi-autonomous regional leaders that emerged in that time, such as Osman Pazvantoğlu, he took advantage of a weak Ottoman government to expand his territory still further until he gained de facto control of most of Southern Albania, western Greece and the Peloponnese, either directly or through his sons.

Ali's policy as ruler of Ioánnina was governed by little more than simple expediency; he operated as a semi-independent despot and allied himself with whoever offered the most advantage at the time. In order to gain a seaport on the Ionian coast Ali formed an alliance with Napoleon I of France who had established Francois Pouqueville as his general consul in Ioánnina. After the Treaty of Tilsitt where Napoleon granted the Czar his plan to dismantle the Ottoman Empire, Ali switched sides and allied with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1807. His machinations were permitted by the Ottoman government in Constantinople for a mixture of expediency – it was deemed better to have Ali as a semi-ally than as an enemy – and weakness, as the central government did not have enough strength to oust him at that time.

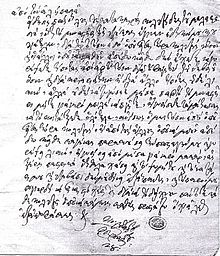

The poet George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron visited Ali's court in Ioánnina in 1809 and recorded the encounter in his work Childe Harold. He evidently had mixed feelings about the despot, noting the splendour of Ali's court and the Greek cultural revival that he had encouraged in Ioánnina, which Byron described as being "superior in wealth, refinement and learning" to any other Greek town. In a letter to his mother, however, Byron deplored Ali's cruelty: "His Highness is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave, so good a general that they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte ... but as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels, etc.."

In 1820, Ali ordered the assassination of a political opponent in Constantinople. The reformist Sultan Mahmud II, who sought to restore the authority of the Sublime Porte, took this opportunity to move against Ali by ordering his deposition. Ali refused to resign his official posts and put up a formidable resistance to Ottoman troop movements, indirectly helping the Greek Independence as some 20,000 Turkish troops were fighting Ali's formidable army.On 4 December 1820 Ali Pasha and the Souliotes formed an anti-Ottoman coalition, in which the Souliotes contributed 3,000 soldiers. Ali Pasha gained the support of Souliotes mainly because he offered to allow the return of the Souliotes in their land and partially because of Ali's appeal based on shared Albanian origin.[3][3] Initially the coalition was successful and managed to control most of the region, but when the Muslim Albanian troops of Ali Pasha were informed of the beginning of the Greek revolts in the Morea they abandoned it.[4] In January 1822, however, Ottoman agents assassinated Ali Pasha and sent his head to the Sultan. After his death, the pashalik ceased to exist and was merged with Pashalik of Berat for creating again Janina Vilayet with Sanjak of Ioannina, Sanjak of Berat, Gjirokastër and Preveza.

See also

- Albania under the Ottoman Empire

- Albanian Pashaliks

- Greece under the Ottoman Empire

- Pashalik of Berat

- Pashalik of Scutari

References

- ^ Gawrych George Walter. The crescent and the eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. I.B.Tauris, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84511-287-5, p. 26: At that time, Tepelenli Ali Pasha, who reinged from 1788 to 1822 "used Greek for all his courtly dealing".

- ^ a b Albania and the surrounding world: papers from the British Albanian Colloquium, South East European Studies Association held at Pembroke College, Cambridge, 29th–31st March, 1994

- ^ a b Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth (1999). The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4. Retrieved 19 October 2010. Cite error: The named reference "Fleming1999" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson (2001), Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 25, ISBN 978-0-313-31949-5

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|ean=(help)

Sources

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997), Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization, Ekdotike Athenon, p. 480, ISBN 978-960-213-371-2,

p. 380

- Use dmy dates from April 2013

- States and territories established in 1788

- States and territories disestablished in 1822

- 1822 disestablishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th century in Greece

- 19th century in Greece

- States and territories established in 1787

- Ottoman Epirus

- Eyalets of the Ottoman Empire in Europe

- Ottoman Albania

- Ottoman Greece

- 1788 establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 18th-century establishments in Greece