Peterhouse, Cambridge

| Peterhouse | |

|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | |

Old Court, facing the Chapel | |

Arms of Peterhouse Arms: Or four pallets Gules within a border of the last charged with eight ducal coronets of the first | |

| Scarf colours: four equal stripes alternating white and blue | |

| Location | Trumpington Street (map) |

| Full name | The Master (or Keeper) and Fellows of Peterhouse in the University of Cambridge[1] |

| Abbreviation | PET[2] |

| Founder | Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely |

| Established | 1284 |

| Named after | Peter the Apostle |

| Previous names |

|

| Sister colleges | Merton College, Oxford |

| Master | Professor Andy Parker |

| Undergraduates | 290 (2022–23) |

| Postgraduates | 187 (2022–23) |

| Endowment | £235.1 million (2022)[3] |

| Website | www |

| JCR | www |

| MCR | www |

| Boat club | www |

| Map | |

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Peterhouse has around 300 undergraduate and 175 graduate students, and 54 fellows.[4]

Peterhouse alumni are notably eminent within the natural sciences, including scientists Lord Kelvin, Henry Cavendish, Charles Babbage, James Clerk Maxwell, James Dewar, Frank Whittle, and five Nobel prize winners in science: Sir John Kendrew, Sir Aaron Klug, Archer Martin, Max Perutz, and Michael Levitt.[5] Peterhouse alumni also include the Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift, Lord Chancellors, Lord Chief Justices, important poets such as Thomas Gray, the first British Fields Medallist Klaus Roth, Oscar-winning film director Sam Mendes and comedian David Mitchell. British Prime Minister Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, and Elijah Mudenda, second prime minister of Zambia, also studied at the college.

Peterhouse is one of the wealthiest colleges in Cambridge,[6] with assets exceeding £350 million.[7] It is currently third in terms of net assets per student. Members of Peterhouse are encouraged to attend communal dinners, known as "Hall". Hall takes place in two sittings, with the second known as "Formal Hall", which consists of a three-course candlelit meal and which must be attended wearing suits and gowns. At Formal Hall, the students rise as the fellows proceed in, a gong is rung, and two Latin graces are read. Peterhouse also hosts a biennial white-tie ball as part of May Week celebrations.

In recent years, Peterhouse has been ranked as one of the highest achieving colleges in Cambridge, although academic performance tends to vary year to year due to its small population. In the past five years, it has sat in the top ten of the 29 colleges within the Tompkins Table. Peterhouse sat at fourth in 2018 and 2019.

History

[edit]

Foundation

[edit]The foundation of Peterhouse dates to 1280, when letters patent from Edward I dated Burgh, Suffolk, 24 December 1280 allowed Hugh de Balsham, to keep a number of scholars in the Hospital of St John,[8] where they were to live according to the rules of the scholars of Merton.[9] After disagreement between the scholars and the Brethren of the Hospital, both requested a separation.[10] As a result, in 1284 Balsham transferred the scholars to the present site with the purchase of two houses just outside the then Trumpington Gate to accommodate a Master and fourteen "worthy but impoverished Fellows". The Church of St Peter without Trumpington Gate was to be used by the scholars.[10] Bishop Hugo de Balsham died in 1286, bequeathing 300 marks that were used to buy further land to the south of St Peter's Church, on which the college's Hall was built.

The earliest surviving set of statutes for the college was given to it by the then Bishop of Ely, Simon Montacute, in 1344. Although based on those of Merton College, these statutes clearly display the lack of resources then available to the college. They were used in 1345 to defeat an attempt by Edward III to appoint a candidate of his own as scholar. In 1354–55, William Moschett set up a trust that resulted in nearly 70 acres (280,000 m2) of land at Fen Ditton being transferred to the College by 1391–92. The College's relative poverty was relieved in 1401 when it acquired the advowson and rectory of Hinton through the efforts of Bishop John Fordham and John Newton. During the reign of Elizabeth I, the college also acquired the area formerly known as Volney's Croft, which today is the area of St Peter's Terrace, the William Stone Building and the Scholars' Garden.

16th century onwards

[edit]In 1553, Andrew Perne was appointed Master. His religious views were pragmatic enough to be favoured by both Mary I, who gave him the Deanery of Ely, and Elizabeth I. A contemporary joke was that the letters on the weathervane of St Peter's Church could represent "Andrew Perne, Papist" or "Andrew Perne, Protestant" according to which way the wind was blowing.[10] Having previously been close to the reformist Regius Chair of Divinity, Martin Bucer, later as vice-chancellor of the university Perne would have Bucer's bones exhumed and burnt in Market Square. John Foxe in his Actes and Monuments singled this out as "shameful railing". There is a hole burnt in the middle of the relevant page in Perne's own copy of Foxe.[11] Perne died in 1589, leaving a legacy to the college that funded a number of fellowships and scholarships, as well bequeathing an extensive collection of books. This collection and rare volumes since added to it is now known as the Perne Library.

Between 1626 and 1634, the Master was Matthew Wren. Wren had previously accompanied Charles I on his journey to Spain to attempt to negotiate the Spanish Match. Wren was a firm supporter of Archbishop William Laud, and under Wren the college became known as a centre of Arminianism. This continued under the Mastership of John Cosin, who succeeded Wren in 1634. Under Cosin significant changes were made to the college's Chapel to bring it into line with Laud's idea of the "beauty of holiness".[10] On 13 March 1643, in the early stages of the English Civil War, Cosin was expelled from his position by a Parliamentary ordinance from the Earl of Manchester. The Earl stated that he was deposed "for his opposing the proceedings of Parliament, and other scandalous acts in the University".[12] On 21 December of the same year, statues and decorations in the Chapel were pulled down by a committee led by the Puritan zealot William Dowsing.[10][13]

The college was the first in the University to have electric lighting installed, when Lord Kelvin provided it for the Hall and Combination Room to celebrate the College's six-hundredth anniversary in 1883–1884. It was the second building in the country to get electric lighting, after the Palace of Westminster.[5]

The college developed a strong reputation for the teaching of history from the time of Harold Temperley,[14] and during World War II its fellowship simultaneously included four professors in the university's faculty for that subject – Herbert Butterfield, David Knowles, Michael Postan and Denis Brogan.[15]

Modern day

[edit]In the 1980s Peterhouse acquired an association with Conservative politics. Maurice Cowling and Roger Scruton were both influential fellows of the College and are sometimes described as key figures in the so-called "Peterhouse right" – an intellectual movement linked to philosophical conservativism.[16] While often associated with Thatcherite politics (notably, the Conservative politicians Michael Portillo and Michael Howard both studied at Peterhouse), the extent to which Margaret Thatcher's economic liberalism was admired within the movement was limited. During this period, which coincided with the mastership of Hugh Trevor-Roper, the college endured a period of significant conflict among the fellowship, particularly between Trevor-Roper and Cowling.[17]

Trevor-Roper feuded constantly with Cowling and his allies, while launching a series of administrative reforms. Women were admitted in 1983 at his urging. The British journalist Neal Ascherson summarised the quarrel between Cowling and Trevor-Roper as:

Lord Dacre, far from being a romantic Tory ultra, turned out to be an anti-clerical Whig with a preference for free speech over superstition. He did not find it normal that fellows should wear mourning on the anniversary of General Franco's death, attend parties in SS uniform or insult black and Jewish guests at high table. For the next seven years, Trevor-Roper battled to suppress the insurgency of the Cowling clique ("a strong mind trapped in its own glutinous frustrations"), and to bring the college back to a condition in which students might actually want to go there. Neither side won this struggle, which soon became a campaign to drive Trevor-Roper out of the college by grotesque rudeness and insubordination.[18]

In a review of Adam Sisman's 2010 biography of Trevor-Roper, the Economist wrote that picture of Peterhouse in the 1980s was "startling", stating the college had become under Cowling's influence a sort of right-wing "lunatic asylum", who were determined to sabotage Trevor-Roper's reforms.[19] In 1987 Trevor-Roper retired complaining of "seven wasted years."[20]

Peterhouse may have been one of the sources of inspiration for Tom Sharpe's Porterhouse Blue.[21]

In the 21st century Peterhouse has established a more modern and welcoming reputation.[citation needed]

Buildings and grounds

[edit]

Peterhouse has its main site situated on Trumpington Street, to the south of Cambridge's town centre. The main portion of the college is just to the north of the Fitzwilliam Museum, and its grounds run behind the museum. The buildings date from a wide variety of times, and have been much altered over the years. The college is reputed to have been at least partially destroyed by fire in 1420. The entrance of the college has shifted through its lifetime as well, with the change being principally the result of the demolition of the row of houses that originally lined Trumpington Street on the east side of the college. In 1574, a map shows the entrance being on the south side of a single main court. The modern entrance is to the east, straight onto Trumpington Street.[8]

First Court

[edit]The area closest to Trumpington Street is referred to as First Court. It is bounded to the north by the Burrough's Building (added in the 18th century), to the east by the street, to the south by the Porters' lodge and to the west by the chapel. Above the Porters' lodge is the Perne Library, named in honour of Andrew Perne, a former Master, and originally built in 1590 to house the collection that he donated to the college. It was extended towards the road in 1633 and features interior woodwork that was added in 1641–48 by William Ashley, who was also responsible for similar woodwork in the chapel.[22] Electric lighting was added to the library in 1937.[23] The area above the Perne Library was used as the Ward Library (the college's general purpose library) from 1952 to 1984, but that has now been moved to its own building in the north-west corner of the college site.[24]

Burrough's Building

[edit]The Burrough's Building is situated at the front of the college, parallel to the Chapel. It is named after its architect, Sir James Burrough, the Master of Caius,[25] and was built in 1736. It is one of several Cambridge neo-Palladian buildings designed by Burrough. Others include the remodelling of the Hall and Old Court at Trinity Hall and the chapel at Clare College. The building is occupied by fellows and college offices.

Old Court

[edit]

Old Court lies beyond the Chapel cloisters. To the south of the court is the dining hall, the only College building that survives from the 13th century. Between 1866 and 1870, the hall was restored by the architect George Gilbert Scott, Jr. Under Scott, the timber roof was repaired and two old parlours merged to form a new Combination Room. The stained glass windows were also replaced with Pre-Raphaelite pieces by William Morris, Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones.[10] The fireplace (originally built in 1618) was restored with tiles by Morris, including depictions of St Peter and Hugo de Balsham.[26] The hall was extensively renovated in 2006-7.

The north and west sides of Old Court were added in the 15th century, and classicised in the 18th century.[10] The chapel makes up the fourth, east side to the court. Rooms in Old Court are occupied by a mixture of fellows and undergraduates. The north side of the court also house Peterhouse's MCR (Middle Combination Room).

Chapel

[edit]

Viewed from the main entrance to Peterhouse on Trumpington Street, the altar end of the Chapel is the most immediately visible building. The Chapel was built in 1628 when the Master of the time Matthew Wren (Christopher Wren's uncle) demolished the college's original hostels. Previously the college had employed the adjacent Church of St Mary the Less as its chapel. The Chapel was consecrated on 17 March 1632 by Dr Francis White, Bishop of Ely.[8] The building's style reflects the contemporary religious trend towards Arminianism. The Laudian Gothic style of the Chapel mixes Renaissance details but incorporated them into a traditional Gothic building. The Chapel's Renaissance architecture contains a Pietà altarpiece and a striking ceiling of golden suns. Its placement in the centre of one side of a court, between open colonnades is unusual, being copied for a single other college (Emmanuel) by Christopher Wren.[27] The original stained glass was destroyed by Parliamentarians in 1643, with only the east window's crucifixion scene (based on Rubens's Le Coup de Lance) surviving.[nb 1] The current side windows are by Max Ainmiller, and were added in 1855. The cloisters on each side of the Chapel date from the 17th century. Their design was classicised in 1709, while an ornamental porch was removed in 1755. The Peterhouse Partbooks, music manuscripts from the early years of the Chapel, survive, and are one of the most important collections of Tudor and Jacobean church music. The Chapel Choir, one of the smallest in Cambridge, has recently attracted wider interest for its regular performances of this material, some of which has not been heard since the 16th century. The restoration of the 1763 John Snetzler organ in the Chapel was by Noel Mander.

The first person buried in the Chapel was Samuel Horne, a fellow of the college.[8] Horne was probably chaplain.

Gisborne Court

[edit]Gisborne Court is accessible through an archway leading from the west side of Old Court. It was built in 1825-6.[10] Its cost was met with part of a benefaction of 1817 from the Rev. Francis Gisborne, a former fellow. The court is built in white brick with stone dressings in a simple Gothic revival style from the designs of William McIntosh Brookes. Only three sides to the court were built, with the fourth side being a screen wall. The wall was demolished in 1939, leaving only its footing.[29] Rooms in Gisborne Court are mainly occupied by undergraduates. Many previously housed distinguished alumni, including Lord Kelvin in I staircase.

Whittle Building

[edit]The Whittle Building, named after Petrean Frank Whittle, opened on the western side of Gisborne Court in early 2015. Designed in neo-gothic style by John Simpson Architects, it contains en-suite undergraduate accommodation, the student bar and common room, a function room and a gym. Its design recalls that of the original screen-wall that once stood in its place.[30] In 2015 the building was shortlisted for the Carbuncle Cup, given annually by the magazine Building Design to "the ugliest building in the United Kingdom completed in the last 12 months".[31][32]

Fen Court

[edit]Beyond Gisborne Court is Fen Court, a 20th-century building partially on stilts. Fen Court was built between 1939 and 1941 from designs by H. C. Hughes and his partner Peter Bicknell.[33] It was amongst the earliest buildings in Cambridge designed in the style of the Modern Movement pioneered by Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus. The carved panel by Anthony Foster over the entrance doorway evokes the mood in Britain as the building was completed. It bears the inscription DE PROFUNDIS CLAMAVI MCMXL — "out of the depths have I cried out 1940". These are the first words of Psalm 130, one of the Penitential Psalms. Alongside the inscription is a depiction of St Peter being saved from the sea.

An adjacent bath-house, known as the Birdwood Building, used to make up the western side of Gisborne Court. This was also designed by Hughes and Bicknell, and was built between 1932 and 1934.[33] It was demolished in 2013 to make way for the new Whittle Building.

Ward Library

[edit]

The north-west corner of the main site is occupied by former Victorian warehouses containing the Ward Library, as well as a theatre and function room. The building it is housed in was originally the University's Museum of Classical Archaeology and was designed by Basil Champneys in 1883. It was adapted to its modern purpose by Robert Potter in 1982 and opened in its current form as a library two years later. In recent years, the final gallery of the old museum building has been converted into a reading room, named the Gunn Gallery, after Dr Chan Gunn.[34]

Gardens

[edit]

While officially being named the Grove, the grounds to the south of Gisborne Court have been known as the Deer Park since deer were brought there in the 19th century. During that period it achieved fame as the smallest deer park in England. After the First World War the deer sickened and passed their illness onto stock that had been imported from the Duke of Portland's estate at Welbeck Abbey in an attempt to improve the situation. There are no longer any deer.

The remainder of the college's gardens divide into areas known as the Fellows' Garden, just to the south of Old Court, and the Scholars' Garden, at the south end of the site, surrounding the William Stone Building.

William Stone Building

[edit]

The William Stone Building stands in the Scholars' Garden and was funded by a £100,000 bequest from William Stone (1857–1958), a former scholar of the college. Erected in 1963-4, to a design by Sir Leslie Martin and Sir Colin St John Wilson, it is an eight-storey brick tower[35] housing eight fellows and 24 undergraduates. It has been refurbished, converting the rooms to en-suite.

Trumpington Street

[edit]The college also occupies a number of buildings on Trumpington Street.[36]

Master's Lodge

[edit]

The Master's Lodge is situated across Trumpington Street from the College, and was bequeathed to the College in 1727 by a fellow, Dr Charles Beaumont, son of the 30th Master of the college, Joseph Beaumont. It is built in red brick in the Queen Anne style.[5]

The Hostel

[edit]The Hostel is situated next to the Master's Lodge. It was built in a neo-Georgian style in 1926 from designs by Thomas Henry Lyon. The Hostel was intended to be part of a larger complex but only one wing was built. It currently houses undergraduates and some fellows. During World War II the London School of Economics was housed in The Hostel and nearby buildings, at the invitation of the Master and Fellows.[37]

Cosin Court

[edit]Behind the Hostel lies Cosin Court, which provides accommodation for fellows and mature, postgraduate, and married students. The court is named for John Cosin (1594–1672) who was successively Master of Peterhouse, Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and Prince-Bishop of Durham.

St Peter's Terrace

[edit]

This row of Georgian townhouses houses first-year undergraduates, fellows, and some graduate students in basement flats. It is directly in front of the William Stone Building.[38]

Arms

[edit]The College has, during its history, used five different coats of arms. The one currently in use has two legitimate blazons. The first form is the original grant by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms, in 1575:

- Or four pallets Gules within a border of the last charged with eight ducal coronets of the first.

The College did, however, habitually use a version with three pallets, and this was allowed at the Herald's Visitation of Cambridgeshire in 1684. The latter version (with three pallets) was officially adopted by the Governing Body in 1935. The construction of the arms is that of the founder, Hugo de Balsham, surrounded by the crowns of the See of Ely.[39]

Grace

[edit]| Latin | English |

|---|---|

Benedic nos Domine, et dona Tua, quae de Tua largitate sumus sumpturi, et concede, ut illis salubriter nutriti, Tibi debitum obsequium praestare valeamus, per Christum Dominum nostrum, Amen. Deus est caritas, et qui manet in caritate in Deo manet, et Deus in eo: sit Deus in nobis, et nos maneamus in ipso. Amen. |

Bless us, O Lord, and Thy gifts, which of Thy bounty we are about to receive, and grant that, fed wholesomely upon them, we may be able to offer due service unto Thee, through Christ our Lord, Amen.

God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him: let God be in us, and let us remain in the same. Amen. |

Peterhouse and Jesus College are the only two colleges to have two separate halves to their grace, the first being a standard grace, and the second a quotation of 1 John 4:16.

People associated with Peterhouse

[edit]Members of Peterhouse — as masters, fellows (including honorary fellows) or students — are known as Petreans.[40]

-

John Whitgift

Archbishop of Canterbury -

The Duke of Grafton

Prime Minister of Great Britain -

Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough

Lord Chief Justice -

Syed Mohammad Hadi

Sportsman -

Herbert Butterfield

Historian, philosopher, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge -

James Mason

Actor -

Niall Ferguson

Historian -

Michael Portillo

broadcaster and former politician -

Roger Scruton

Philosopher -

Sam Mendes Film and stage director, producer and screenwriter

Nobel laureates

[edit]Peterhouse has five Nobel laureates associated with it, either as former students or fellows.

- John Kendrew – Chemistry (1962) for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography.

- Sir Aaron Klug – Chemistry (1982) for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy.

- Michael Levitt – Chemistry (2013) for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems.

- Archer Martin – Chemistry (1952) for his invention of partition chromatography.

- Max Perutz – Chemistry (1962) for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography.

Gallery

[edit]-

Chapel and main entrance

-

Part of St Peter's College, view from the private gardens, 1815

-

St Peter's College, Chapel, 1815

-

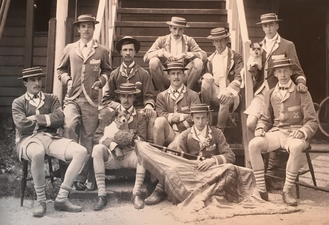

Peterhouse May Boat Crew, 1896

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "We went to Peter-house, 1643, December 21, with officers and soldiers, and in the presence of Mr. Hanscott, Mr. Wilson, the President Mr. Francis, Mr. Maxey, and other Fellows... We pulled down two mighty great angells, with wings, and divers other angells, and the 4 Evangelists, and Peter, with his keies on the chappell door and about a hundred chirubims and angells, and divers superstitious letters in gold."[28]

References

[edit]- ^ "THE MASTER (OR KEEPER) AND FELLOWS OF PETERHOUSE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE - Charity 1137457".

- ^ University of Cambridge (6 March 2019). "Notice by the Editor". Cambridge University Reporter. 149 (Special No 5): 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ https://www.pet.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/inline-files/2022%20Peterhouse_3006FSS_Client%20signed%2815467985_1%29_0.PDF [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Fellows by Seniority". Peterhouse, Cambridge. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "About the College". Peterhouse Website. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Oxford and Cambridge university colleges hold £21bn in riches". TheGuardian.com. 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Annual Report and Accounts 2023" (PDF). Peterhouse College, Cambridge. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Charles Henry (1860). Memorials of Cambridge. Cambridge: William Metcalfe.

- ^ "'The colleges and halls: Peterhouse', A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge (1959), pp. 334–340". Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walker, Thomas Alfred (1935). Peterhouse. Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons Ltd.

- ^ Patrick Collinson, ‘Perne, Andrew (1519?–1589)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004).

- ^ Walker, John (1863). Robert Whittaker (ed.). The sufferings of the clergy of the Church of England during the great rebellion. London. p. 169. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Richard Crashaw". The Living Age. 157: 198. 28 April 1883. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Soffer, Reba N. (2009). History, Historians, and Conservatism in Britain and America: From the Great War to Thatcher and Reagan. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-19920-811-1.

- ^ Latham, A. J. H. (2007). "W. A. Cole". In Lyons, John S.; Cain, Louis P.; Williamson, Samuel H. (eds.). Reflections on the Cliometrics Revolution: Conversations with Economic Historians. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-13599-360-3.

- ^ "Peterhouse blues". The Guardian. 10 September 1999. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Maurice Cowling Obituary". The Times. London. 26 August 2005. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Ascherson, Neal (19 August 2010). "The Liquidator". London Review of Books. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Not so ropey". The Economist. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Sisman, Adam (2011). An Honourable Englishman: The Life of Hugh Trevor-Roper. Random House. p. 562. ISBN 9780679604730.

- ^ Sharpe, Tom (1 January 2002). [Porterhouse Blue]. Arrow Books/Random House.

- ^ "Peterhouse, Cambridge". Britain Express. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "The Perne Library". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Over the Perne Library". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "James Burrough". Cambridge 2000. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Hall Chimneypiece". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Old Court, Looking East". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Cooper, Trevor (26 April 2001). The Journal of William Dowsing: Iconoclasm in East Anglia during the English Civil War. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0851158334.

- ^ "Gisborne Court". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Whittle Building". John Simpson Architects. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Watson, Anna (22 July 2010). "Six in race for Carbuncle Cup". bdonline.co.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ "Carbuncle Cup: Whittle Building, Peterhouse, University of Cambridge". BD Online. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b Peterhouse Annual Record 2002/2003

- ^ "History of Peterhouse Libraries". Peterhouse Website. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "William Stone Building". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Map of the College – Peterhouse Cambridge".

- ^ "Peterhouse Images". Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Cambridge 2000: Peterhouse: Trumpington Street: St Peter's Terrace".

- ^ Peterhouse Annual Record 1999/2000

- ^ "Eminent". Petreans. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Halacy, Daniel Stephen (1970). Charles Babbage, Father of the Computer. Crowell-Collier Press. ISBN 0-02-741370-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Peterhouse, Cambridge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Peterhouse, Cambridge at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

![Charles Babbage Inventor of the difference engine, "Father of the computer"[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/CharlesBabbage.jpg/101px-CharlesBabbage.jpg)