Political career of Fidel Castro

An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it. |

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Presidency of Fidel Castro. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2016. |

Fidel Castro served as Prime Minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976. In 1976, Castro became President of Cuba.

Consolidating leadership: 1959

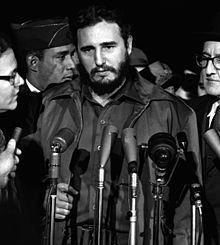

On February 16, 1959, Castro was sworn in as Prime Minister of Cuba, and accepted the position on the condition that the Prime Minister’s powers be increased.[1] Between 15 and 26 April Castro visited the U.S. with a delegation of representatives, hired a public relations firm for a charm offensive and presented himself as a "man of the people". U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower avoided meeting Castro; he was instead met by Vice President Richard Nixon, a man Castro instantly disliked.[2] Proceeding to Canada, Trinidad, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, Castro attended an economic conference in Buenos Aires, unsuccessfully proposing a $30 billion U.S.-funded "Marshall Plan" for Latin America.[3]

After appointing himself president of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria - INRA), on 17 May 1959, Castro signed into law the First Agrarian Reform, limiting landholdings to 993 acres (4.02 km2) per owner and forbid further foreign land-ownership. Large land-holdings were broken up and redistributed; an estimated 200,000 peasants received title deeds. To Castro, this was an important step, that broke the control of the landowning class over Cuba’s agriculture; popular among the working class, it alienated many middle-class supporters.[4] Castro appointed himself president of the National Tourist Industry, introducing unsuccessful measures to encourage African-American tourists to visit, advertising it as a tropical paradise free of racial discrimination.[5] Changes to state wages were implemented; judges and politicians had their pay reduced while low-level civil servants saw theirs raised.[6] In March 1959, Castro ordered rents for those who paid less than $100 a month halved, with measures implemented to increase the Cuban people’s purchasing powers; productivity decreased and the country’s financial reserves were drained within two years.[7]

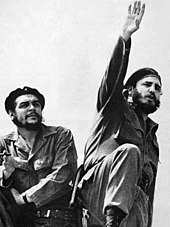

Although he refused to categorize his regime as socialist and repeatedly denied being a communist, Castro appointed Marxists to senior government and military positions; most notably Che Guevara became Governor of the Central Bank and then Minister of Industries. Appalled, Air Force commander Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz defected to the U.S.[8] Although President Urrutia denounced the defection, he publicly expressed concern with the rising influence of Marxism. Angered, Castro announced his resignation as Prime Minister, blaming Urrutia for complicating government with his "fevered anti-Communism". Over 500,000 Castro-supporters surrounded the Presidential Palace demanding Urrutia’s resignation, which was duly received. On July 23, Castro resumed his Premiership and appointed the Marxist Osvaldo Dorticós as the new President.[9]

"Until Castro, the U.S. was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that the American ambassador was the second most important man, sometimes even more important than the Cuban president."

— Earl T. Smith, former American Ambassador to Cuba, during 1960 testimony to the U.S. Senate[10]

Castro used radio and television to develop a "dialogue with the people", posing questions and making provocative statements.[11] His regime remained popular with workers, peasants and students, who constituted the majority of the country’s population,[12] while opposition came primarily from the middle class; thousands of doctors, engineers and other professionals emigrated to Florida in the U.S., causing an economic brain drain.[13] Castro’s government cracked down on opponents of his government, and arrested hundreds of counter-revolutionaries.[14] Castro’s government sanctioned the use of psychological torture, subjecting prisoners to solitary confinement, rough treatment, and threatening behavior.[15] Militant anti-Castro groups, funded by exiles, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and Trujillo’s Dominican government, undertook armed attacks and set up guerrilla bases in Cuba’s mountainous regions. This led to a six-year Escambray Rebellion that lasted longer and involved more soldiers than the revolution. The government won with superior numbers and executed those who surrendered.[16] After conservative editors and journalists expressed hostility towards the government, the pro-Castro printers' trade union disrupted editorial staff, and in January 1960 the government proclaimed that each newspaper would be obliged to publish a "clarification" written by the printers' union at the end of any articles critical of the government; thus began press censorship in Castro’s Cuba.[17]

Soviet support and U.S. opposition: 1960

By 1960, the Cold War raged between two superpowers: the United States, a capitalist liberal democracy, and the Soviet Union (USSR), a Marxist-Leninist socialist state ruled by the Communist Party. Expressing contempt for the U.S., Castro shared the ideological views of the USSR, establishing relations with several Marxist-Leninist states.[18] Meeting with Soviet First Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan, Castro agreed to provide the USSR with sugar, fruit, fibers, and hides, in return for crude oil, fertilizers, industrial goods, and a $100 million loan.[19] Cuba’s government ordered the country's refineries – then controlled by the U.S. corporations Shell, Esso and Standard Oil – to process Soviet oil, but under pressure from the U.S. government, they refused. Castro responded by expropriating and nationalizing the refineries. In retaliation, the U.S. cancelled its import of Cuban sugar, provoking Castro to nationalize most U.S.-owned assets on the island, including banks and sugar mills.[20]

Relations between Cuba and the U.S. were further strained following the explosion of a French vessel, the Le Coubre, in Havana harbor in March 1960. The ship carried weapons purchased from Belgium, the cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly insinuated that the U.S. government were guilty of sabotage. He ended this speech with "¡Patria o Muerte!" ("Fatherland or Death"), a proclamation that he made much use of in ensuing years.[21] Inspired by their earlier success with the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, on 17 March 1960, U.S. President Eisenhower secretly authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to overthrow Castro's government. He provided them with a budget of $13 million and permitted them to ally with the Mafia, who were aggrieved that Castro's government closed down their businesses in Cuba.[22] On 13 October 1960, the U.S. prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba, initiating an economic embargo. In retaliation, INRA took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 U.S. companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized.[23] On 16 December, the U.S. ended its import quota of Cuban sugar, the country's primary export.[24]

In September 1960, Castro flew to New York City for the General Assembly of the United Nations. Offended by the attitude of the elite Shelburne Hotel, he and his entourage stayed at the cheap, run-down Hotel Theresa in the impoverished area of Harlem. There he met with journalists and anti-establishment figures like Malcolm X. He also met the Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev and the two leaders publicly highlighted the poverty faced by U.S. citizens in areas like Harlem; Castro described New York as a "city of persecution" against black and poor Americans. Relations between Castro and Khrushchev were warm; they led the applause to one another's speeches at the General Assembly. Although Castro publicly denied being a socialist, Khrushchev informed his entourage that the Cuban would become "a beacon of Socialism in Latin America."[25] Subsequently visited by four other socialists, Polish First Secretary Władysław Gomułka, Bulgarian Chairman Todor Zhivkov, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Indian Premier Jawaharlal Nehru,[26] the Fair Play for Cuba Committee organized an evening’s reception for Castro, attended by Allen Ginsberg, Langston Hughes, C. Wright Mills and I. F. Stone.[27]

Castro returned to Cuba on 28 September. He feared a U.S.-backed coup and in 1959 spent $120 million on Soviet, French and Belgian weaponry. Intent on constructing the largest army in Latin America, by early 1960 the government had doubled the size of the Cuban armed forces.[28] Fearing counter-revolutionary elements in the army, the government created a People's Militia to arm citizens favorable to the revolution, and trained at least 50,000 supporters in combat techniques.[29] In September 1960, they created the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), a nationwide civilian organization which implemented neighborhood spying to weed out "counter-revolutionary" activities and could support the army in the case of invasion. They also organized health and education campaigns, and were a conduit for public complaints. Eventually, 80% of Cuba's population would be involved in the CDR.[30] Castro proclaimed the new administration a direct democracy, in which the Cuban populace could assemble en masse at demonstrations and express their democratic will. As a result, he rejected the need for elections, claiming that representative democratic systems served the interests of socio-economic elites.[31] In contrast, critics condemned the new regime as un-democratic. The U.S. Secretary of State Christian Herter announced that Cuba was adopting the Soviet model of communist rule, with a one-party state, government control of trade unions, suppression of civil liberties and the absence of freedom of speech and press.[32]

Castro's government emphasised social projects to improve Cuba's standard of living, often to the detriment of economic development.[33] Major emphasis was placed on education, and under the first 30 months of Castro's government, more classrooms were opened than in the previous 30 years. The Cuban primary education system offered a work-study program, with half of the time spent in the classroom, and the other half in a productive activity.[34] Health care was nationalized and expanded, with rural health centers and urban polyclinics opening up across the island, offering free medical aid. Universal vaccination against childhood diseases was implemented, and infant mortality rates were reduced dramatically.[33] A third aspect of the social programs was the construction of infrastructure; within the first six months of Castro's government, 600 miles of road had been built across the island, while $300 million was spent on water and sanitation schemes.[33] Over 800 houses were constructed every month in the early years of the administration in a measure to cut homelessness, while nurseries and day-care centers were opened for children and other centers opened for the disabled and elderly.[33]

The Bay of Pigs Invasion and embracing socialism: 1961–62

"There was... no doubts about who the victors were. Cuba's stature in the world soared to new heights, and Fidel's role as the adored and revered leader among ordinary Cuban people received a renewed boost. His popularity was greater than ever. In his own mind he had done what generations of Cubans had only fantasized about: he had taken on the United States and won."

— Peter Bourne, Castro biographer, 1986 [35]

In January 1961, Castro ordered Havana's U.S. Embassy to reduce its 300 staff, suspecting many to be spies. The U.S. responded by ending diplomatic relations, and increasing CIA funding for exiled dissidents; these militants began attacking ships trading with Cuba, and bombed factories, shops, and sugar mills.[36] Both Eisenhower and his successor John F. Kennedy supported a CIA plan to aid a dissident militia, the Democratic Revolutionary Front, to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro; the plan resulted in the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. On 15 April, CIA-supplied B-26's bombed three Cuban military airfields; the U.S. announced that the perpetrators were defecting Cuban air force pilots, but Castro exposed these claims as false flag misinformation.[37] Fearing invasion, he ordered the arrest of between 20,000 and 100,000 suspected counter-revolutionaries,[38] publicly proclaiming that "What the imperialists cannot forgive us, is that we have made a Socialist revolution under their noses". This was his first announcement that the government was socialist.[39]

The CIA and Democratic Revolutionary Front had based a 1,400-strong army, Brigade 2506, in Nicaragua. At night, Brigade 2506 landed along Cuba's Bay of Pigs, and engaged in a firefight with a local revolutionary militia. Castro ordered Captain José Ramón Fernández to launch the counter-offensive, before taking personal control himself. After bombing the invader's ships and bringing in reinforcements, Castro forced the Brigade's surrender on 20 April.[40] He ordered the 1189 captured rebels to be interrogated by a panel of journalists on live television, personally taking over questioning on 25 April. 14 were put on trial for crimes allegedly committed before the revolution, while the others were returned to the U.S. in exchange for medicine and food valued at U.S. $25 million.[41] Castro's victory was a powerful symbol across Latin America, but it also increased internal opposition primarily among the middle-class Cubans who had been detained in the run-up to the invasion. Although most were freed within a few days, many left Cuba for the United States and established themselves in Florida.[42]

Consolidating "Socialist Cuba", Castro united the MR-26-7, Popular Socialist Party and Revolutionary Directorate into a governing party based on the Leninist principle of democratic centralism: the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (Organizaciones Revolucionarias Integradas - ORI), renamed the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution (PURSC) in 1962.[43] Although the USSR was hesitant regarding Castro's embrace of socialism,[44] relations with the Soviets deepened. Castro sent Fidelito for a Moscow schooling and while the first Soviet technicians arrived in June[45] Castro was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.[46] In December 1961, Castro proclaimed himself a Marxist-Leninist, and in his Second Declaration of Havana he called on Latin America to rise up in revolution.[47] In response, the U.S. successfully pushed the Organization of American States to expel Cuba; the Soviets privately reprimanded Castro for recklessness, although he received praise from China.[48] Despite their ideological affinity with China, in the Sino-Soviet Split, Cuba allied with the wealthier Soviets, who offered economic and military aid.[49]

The ORI began shaping Cuba using the Soviet model, persecuting political opponents and perceived social deviants such as prostitutes and homosexuals; Castro considered the latter a bourgeois trait.[50] Government officials spoke out against his homophobia, but many gays were forced into the Military Units to Aid Production (Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción - UMAP),[51] something Castro took responsibility for and regretted as a "great injustice" in 2010.[52] By 1962, Cuba's economy was in steep decline, a result of poor economic management and low productivity coupled with the U.S. trade embargo. Food shortages led to rationing, resulting in protests in Cárdenas.[53] Security reports indicated that many Cubans associated austerity with the "Old Communists" of the PSP, while Castro considered a number of them – namely Aníbal Escalante and Blas Roca – unduly loyal to Moscow. In March 1962 Castro removed the most prominent "Old Communists" from office, labelling them "sectarian".[54] On a personal level, Castro was increasingly lonely, and his relations with Che Guevara became strained as the latter became increasingly anti-Soviet and pro-Chinese.[55]

The Cuban Missile Crisis and furthering socialism: 1962–1968

Militarily weaker than NATO, Khrushchev wanted to install Soviet R-12 MRBM nuclear missiles on Cuba to even the power balance.[56] Although conflicted, Castro agreed, believing it would guarantee Cuba's safety and enhance the cause of socialism.[57] Undertaken in secrecy, only the Castro brothers, Guevara, Dorticós and security chief Ramiro Valdés knew the full plan.[58] Upon discovering it through aerial reconnaissance, in October the U.S. implemented an island-wide quarantine to search vessels headed to Cuba, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S. saw the missiles as offensive, though Castro insisted they were defensive.[59] Castro urged Khrushchev to threaten a nuclear strike on the U.S. should Cuba be attacked, but Khrushchev was desperate to avoid nuclear war.[60] Castro was left out of the negotiations, in which Khruschev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for a U.S. commitment not to invade Cuba and an understanding that the U.S. would remove their MRBMs from Turkey and Italy.[61] Feeling betrayed by Khruschev, Castro was furious and soon fell ill.[62] Proposing a five-point plan, Castro demanded that the U.S. end its embargo, cease supporting dissidents, stop violating Cuban air space and territorial waters and withdraw from Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Presenting these demands to U Thant, visiting Secretary-General of the United Nations, the U.S. ignored them, and in turn Castro refused to allow the U.N.'s inspection team into Cuba.[63]

In February 1963, Castro received a personal letter from Khrushchev, inviting him to visit the USSR. Deeply touched, Castro arrived in April and stayed for five weeks. He visited 14 cities, addressed a Red Square rally and watched the May Day parade from the Kremlin, was awarded an honorary doctorate from Moscow State University and became the first foreigner to receive the Order of Lenin.[64][65] Castro returned to Cuba with new ideas; inspired by Soviet newspaper Pravda, he amalgamated Hoy and Revolución into a new daily, Granma,[66] and oversaw large investment into Cuban sport that resulted in an increased international sporting reputation.[67] The government agreed to temporarily permit emigration for anyone other than males aged between 15 and 26, thereby ridding the government of thousands of opponents.[68] In 1963 his mother died. This was the last time his private life was reported in Cuba's press.[69] In 1964, Castro returned to Moscow, officially to sign a new five-year sugar trade agreement, but also to discuss the ramifications of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[70] In October 1965, the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations was officially renamed the "Cuban Communist Party" and published the membership of its Central Committee.[68]

"The greatest threat presented by Castro’s Cuba is as an example to other Latin American states which are beset by poverty, corruption, feudalism, and plutocratic exploitation ... his influence in Latin America might be overwhelming and irresistible if, with Soviet help, he could establish in Cuba a Communist utopia."

— Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964 [71]

Despite Soviet misgivings, Castro continued calling for global revolution and the funding militant leftists. He supported Che Guevara’s "Andean project", an unsuccessful plan to set up a guerrilla movement in the highlands of Bolivia, Peru and Argentina, and allowed revolutionary groups from across the world, from the Viet Cong to the Black Panthers, to train in Cuba.[72][73] He considered western-dominated Africa ripe for revolution, and sent troops and medics to aid Ahmed Ben Bella's socialist regime in Algeria during the Sand war. He also allied with Alphonse Massemba-Débat's socialist government in Congo-Brazzaville, and in 1965 Castro authorized Guevara to travel to Congo-Kinshasa to train revolutionaries against the western-backed government.[74][75] Castro was personally devastated when Guevara was subsequently killed by CIA-backed troops in Bolivia in October 1967 and publicly attributed it to Che’s disregard for his own safety.[76][77] In 1966 Castro staged a Tri-Continental Conference of Africa, Asia and Latin America in Havana, further establishing himself as a significant player on the world stage.[78][79] From this conference, Castro created the Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS), which adopted the slogan of "The duty of a revolution is to make revolution", signifying that Havana's leadership of the Latin American revolutionary movement.[80]

Castro’s increasing role on the world stage strained his relationship with the Soviets, now under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev. Asserting Cuba’s independence, Castro refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, declaring it a Soviet-U.S. attempt to dominate the Third World.[81] In turn, Soviet-loyalist Aníbal Escalante began organizing a government network of opposition to Castro, though in January 1968, he and his supporters were arrested for passing state secrets to Moscow.[82] Castro ultimately relented to Brezhnev's pressure to be obedient, and in August 1968 denounced the Prague Spring as led by a "fascist reactionary rabble" and praised the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[83][84][85] Influenced by China's Great Leap Forward, in 1968 Castro proclaimed a Great Revolutionary Offensive, closed all remaining privately owned shops and businesses and denounced their owners as capitalist counter-revolutionaries.[86]

Economic stagnation and Third World politics: 1969–1974

In January 1969, Castro publicly celebrated his administration's tenth anniversary in Revolution Square, using the occasion to ask the assembled crowds if they would tolerate reduced sugar rations, reflecting the country's economic problems.[86] The majority of the sugar crop was being sent to the USSR, but 1969's crop was heavily damaged by a hurricane; the government postponed the 1969/70 New Year holidays in order to lengthen the harvest. The military were drafted in, while Castro, and several other Cabinet ministers and foreign diplomats joined in.[87][88] The country nevertheless failed that year’s sugar production quota. Castro publicly offered to resign, but assembled crowds denounced the idea.[89][90] Despite Cuba’s economic problems, many of Castro’s social reforms remained popular, with the population largely supportive of the "Achievements of the Revolution" in education, medical care and road construction, as well as the government’s policy of "direct democracy".[33][90] Cuba turned to the Soviets for economic help, and from 1970 to 1972, Soviet economists re-planned and organized the Cuban economy, founding the Cuban-Soviet Commission of Economic, Scientific and Technical Collaboration, while Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin visited in 1971.[91] In July 1972, Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), an economic organization of socialist states, although this further limited Cuba’s economy to agricultural production.[92]

In May 1970, Florida-based dissident group Alpha 66 sank two Cuban fishing boats and captured their crews, demanding the release of Alpha 66 members imprisoned in Cuba. Under U.S. pressure, the hostages were released, and Castro welcomed them back as heroes.[90] In April 1971, Castro gained international condemnation for ordering the arrest of dissident poet Herberto Padilla. When Padilla fell ill, Castro visited him in hospital. The poet was released after publicly confessing his guilt. Soon after, the government formed the National Cultural Council to ensure that intellectuals and artists supported the administration.[93] In 1971 he visited Chile, where Marxist President Salvador Allende had been elected as the head of a left-wing coalition. Castro supported Allende's socialist reforms, where he toured the country to give speeches and press conferences. Suspicious of right-wing elements in the Chilean military, Castro advised Allende to purge these before they led a coup. Castro was proven right; in 1973, Chile's military led a coup d'état, banned elections, executed thousands and established a military junta led by Commander-in-Chief Augusto Pinochet.[94][95] Castro proceeded to West Africa to meet socialist Guinean President Sékou Touré, where he informed a crowd of Guineans that theirs was Africa's greatest leader.[96] He then went on a seven-week tour visiting other leftist allies in Africa and Eurasia: Algeria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. On every trip he was eager to meet with ordinary people by visiting factories and farms, chatting and joking with them. Although publicly highly supportive of these governments, in private he urged them to do more to aid revolutionary movements in other parts of the world, in particular in the Vietnam War.[97]

In September 1973, he returned to Algiers to attend the Fourth Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Various NAM members were critical of Castro’s attendance, claiming that Cuba was aligned to the Warsaw Pact and therefore should not be at the conference, particularly as he praised the Soviet Union in a speech that asserted that it was not imperialistic.[98][99] As the Yom Kippur War broke out in October 1973 between Israel and an Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria, Castro’s government sent 4000 troops to prevent Israeli forces from entering Syrian territory.[100] In 1974, Cuba broke off relations with Israel over the treatment of Palestinians during the Israel-Palestine conflict and their increasingly close relationship with the United States. This earned him respect from leaders throughout the Arab world, in particular from the Libyan socialist president Muammar Gaddafi, who became his friend and ally.[101]

That year, Cuba experienced an economic boost, due primarily to the high international price of sugar, but also influenced by new trade credits with Canada, Argentina, and parts of Western Europe.[98][102] A number of Latin American states called for Cuba’s re-admittance into the Organization of American States (OAS), with the U.S. finally conceding in 1975 on Henry Kissinger's advice.[103] Cuba's government called the first National Congress of the Cuban Communist Party, thereby officially announcing Cuba’s status as a socialist state. It adopted a new constitution based on the Soviet model, abolished the position of President and Prime Minister. Castro took the presidency of the newly created Council of State and Council of Ministers, making him both head of state and head of government.[104][105]

References

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 173; Quirk 1993, p. 228.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 174–177; Quirk 1993, pp. 236–242; Coltman 2003, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 177; Quirk 1993, p. 243; Coltman 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 177–178; Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, pp. 159–160, "First Agrarian Reform Law (1959)". Retrieved August 29, 2006..

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 262–269, 281.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 234.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 176–177; Quirk 1993, p. 248; Coltman 2003, pp. 161–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181–183; Quirk 1993, pp. 248–252; Coltman 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Ernesto "Che" Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present), by Douglas Kellner, 1989, Chelsea House Publishers, ISBN 1-55546-835-7, pg 66

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 280; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 195–197; Coltman 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 181, 197; Coltman 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 167; Ros 2006, pp. 159–201; Franqui 1984, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 197; Coltman 2003, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 202; Quirk 1993, p. 296.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 189–190, 198–199; Quirk 1993, pp. 292–296; Coltman 2003, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 205–206; Quirk 1993, pp. 316–319; Coltman 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 201–202; Quirk 1993, p. 302; Coltman 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 202, 211–213; Quirk 1993, pp. 272–273; Coltman 2003, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 214; Quirk 1993, p. 349; Coltman 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 215.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 206–209; Quirk 1993, pp. 333–338; Coltman 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 209–210; Quirk 1993, p. 337.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 339.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 300; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 125; Quirk 1993, p. 300.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233; Quirk 1993, p. 345; Coltman 2003, p. 176.

- ^ Quirk 1993. p. 313.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 330.

- ^ a b c d e Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 275–276; Quirk 1993, p. 324.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 226.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 215–216; Quirk 1993, pp. 353–354, 365–366; Coltman 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 217–220; Quirk 1993, pp. 363–367; Coltman 2003, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 371.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 221–222; Quirk 1993, p. 369; Coltman 2003, pp. 180, 186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 222–225; Quirk 1993, pp. 370–374; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 226–227; Quirk 1993, pp. 375–378; Coltman 2003, pp. 180–184.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 230; Quirk 1993, pp. 387, 396; Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 231, Coltman 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Quirk 1993, p. 405.

- ^ Bourne 1987, pp. 230–234, Quirk, pp. 395, 400–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 232–234, Quirk 1993, pp. 397–401, Coltman 2003, p. 190

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 232, Quirk 1993, p. 397.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 188–189.

- ^ "Castro admits 'injustice' for gays and lesbians during revolution", CNN, Shasta Darlington, August 31, 2010.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 233, Quirk 1993, pp. 203–204, 410–412, Coltman 2003, p. 189.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 234–236, Quirk 1993, pp. 403–406, Coltman 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 258–259, Coltman 2003, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 195.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 238–239, Quirk 1993, p. 425, Coltman 2003, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Coltman 2003, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 239, Quirk 1993, pp. 443–434, Coltman 2003, pp. 199–200, 203.

- ^ Bourne 1986, pp. 241–242, Quirk 1993, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 245–248.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 204–205.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 249.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 213.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 263.

- ^ "Cuba Once More", by Walter Lippmann, Newsweek, April 27, 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 255.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 211.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 255–256, 260.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 211–212.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 267–268.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 216.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 265.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 214.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 267.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 269.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 269–270.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 270–271.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (August 1968). "Castro comments on Czechoslovakia crisis". FBIS.

- ^ a b Coltman 2003. p. 227.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 273.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 229.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 274.

- ^ a b c Coltman 2003. p. 230.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 276–277.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 277.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 232–233.

- ^ Bourne 1986. pp. 278–280.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 233–236, 240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 237–238.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 238.

- ^ a b Bourne 1986. pp. 283–284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 239.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 284.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 239–240.

- ^ Coltman 2003. p. 240.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 282.

- ^ Bourne 1986. p. 283.

- ^ Coltman 2003. pp. 240–241.

Bibliography

- Benjamin, Jules R. (1992). The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution: An Empire of Liberty in an Age of National Liberation. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691025360.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bohning, Don (2005). The Castro Obsession: U.S. Covert Operations Against Cuba, 1959–1965. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1574886764.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bourne, Peter G. (1986). Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 978-0396085188.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coltman, Leycester (2003). The Real Fidel Castro. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300107609.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Geyer, Georgie Anne (1991). Guerrilla Prince: The Untold Story of Fidel Castro. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0316308939.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gott, Richard (2004). Cuba: A New History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300104110.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Quirk, Robert E. (1993). Fidel Castro. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393034851.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Skierka, Volka (2006). Fidel Castro: A Biography. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-0745640815.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Von Tunzelmann, Alex (2011). Red Heat: Conspiracy, Murder, and the Cold War in the Caribbean. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805090673.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)