Proto-orthodox Christianity

The term proto-orthodox Christianity or proto-orthodoxy describes the early Christian movement that was the precursor of Christian orthodoxy. Older literature often referred to the group as "early Catholic" in the sense that their views were the closest to those of the more organized Catholic Church of the 4th and 5th centuries. The term "proto-orthodox" was coined by Bentley Layton, a scholar of Gnosticism and a Coptologist at Yale, but is often attributed to New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman, who has popularized the term by using it in books for a non-academic audience.[2] Ehrman argues that when this group became prominent by the end of the third century, it "stifled its opposition, it claimed that its views had always been the majority position and that its rivals were, and always had been, 'heretics', who willfully 'chose' to reject the 'true belief'."[3]

Early Christianity had many diverse sects and doctrines. Critics of the stance downplaying the proto-orthodox's prominence (such as Larry W. Hurtado) generally argue that the writings of the Catholic anti-heresiologists condemning others as heretics was still essentially accurate: that of all the Christian groups, the "proto-orthodox" has the most common ground with the immediate followers of Jesus in the Apostolic Age and Christianity in the 1st century, and were indeed the most common variety of Christianity even then.

Proto-orthodoxy versus other Christianities

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| History of Christian theology |

|---|

|

|

|

According to Ehrman, "'Proto-orthodoxy' refers to the set of [Christian] beliefs that was going to become dominant in the 4th century, held by people before the 4th century."[4]: 7:57

Ehrman expands on the thesis of German New Testament scholar Walter Bauer (1877–1960), laid out in his primary work Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity (1934). Bauer hypothesised that the Church Fathers, most notably Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History, "had not given an objective account of the relationship of early Christian groups." Instead, Eusebius would have "rewritten the history of early Christian conflicts, so as to validate the victory of the orthodox party that he himself represented."[5]: 11:42 Eusebius claimed that orthodoxy derived directly from the teachings of Jesus and his earliest followers, and had always been the majority view; by contrast, all other Christian views were branded as "heresies", that is to say, willful corruptions of the truth, held by small numbers of minorities.[note 1]

In modern times, many non-orthodox early Christian writings were discovered by scholars, gradually challenging the traditional Eusebian narrative. Bauer was the first to suggest that what later became known as "orthodoxy" was originally just one out of many early Christian sects, such as the Ebionites, Gnostics, and Marcionists, that was able to eliminate all major opposition by the end of the 3rd century, and managed to establish itself as orthodoxy at the First Council of Nicaea (325) and subsequent ecumenical councils. According to Bauer, the early Egyptian churches were largely Gnostic, the 2nd-century churches in Asia Minor were largely Marcionist, and so on. But because the church in the city of Rome was "proto-orthodox", in Ehrman's terms, Bauer contended they had strategic advantages over all other sects because of their proximity to the Roman Empire's centre of power.[5]: 13:43

As the Roman political and cultural elite converted to the locally held form of Christianity, they started exercising their authority and resources to influence the theology of other communities throughout the Roman Empire, sometimes by force. Bauer cites the First Epistle of Clement as an early example of the bishop of Rome interfering with the church of Corinth to impose its own proto-orthodox doctrine of apostolic succession, and to favour a certain group of local church leaders over another.[5]: 15:48

Characteristics

[edit]According to Ehrman, proto-orthodox Christianity bequeathed to subsequent generations "four Gospels to tell us virtually everything we know about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus" and "handed down to us the entire New Testament, twenty-seven books".[6] Similar to later Chalcedonian views about Jesus, the proto-orthodox believed that Christ was both divine as well as a human being, not two halves joined. Likewise they regarded God as three persons; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit; but only one God.[7]

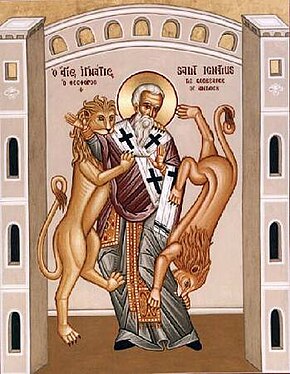

Martyrdom played a major role in proto-orthodox Christianity, as exemplified by Ignatius of Antioch in the beginning of the second century. Imperial authorities arrested him "evidently for Christian activities" and condemned him as fodder for wild beasts.[8] He expressed eagerness to die, expecting thus to "attain to God".[9] Following Ignatius, many proto-orthodox theorists saw it as a privilege to die for faith. In fact, martyrdom became a way to tell the true believers from the heretics. Those who were not willing to die for what they believed were seen as not dedicated to the faith.[10]

Another facet of the faith was the structure of the church. It was common, as it is today, for a church to have a leader. Ignatius wrote several letters to several churches instructing them to let the leaders, usually the bishops, handle all the problems within the church. He exhorted church members to listen to the bishops since they were the leaders: "Be subject to the Bishop as to the commandment…We are clearly obligated to look upon the bishop as the Lord himself ... You should do nothing apart from the bishop."[11] The role of the bishop paved the way for hierarchies in churches that is often seen today.

Another important aspect about proto-orthodox Christianity involves its views on Jews and Jewish practices. An important book for them was the Epistle of Barnabas, which taught that the Jewish interpretation of the Old Testament was improperly literal, and the Epistle offered metaphorical interpretations as the truth, such as on the laws concerning diet, fasting, and the Sabbath. Also, the Old Testament was specifically written to presage the coming of Jesus, Christ's covenant superseded the Mosaic covenant, but also, "the Jews had always adhered to a false religion".[12] Those themes were also developed by the 2nd-century apologist Justin Martyr.[13]

The claimed institutional unity of the Christian Church was propaganda constantly repeated by orthodox Christian writers, rather than a genuine historical reality.[14]

Development of orthodox canon and Christology

[edit]

In order to form a New Testament canon of uniquely Christian works, proto-orthodox Christians went through a process that was complete in the West by the beginning of the 5th century.[15] Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, in his Easter letter of 367,[16] listed the same twenty-seven New Testament books as found in the Canon of Trent. The first council that accepted the present canon of the New Testament may have been the Synod of Hippo Regius in North Africa (393). The acts of this council are lost. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Council of Carthage (397) and the Council of Carthage (419).[17]

To Ehrman, "Proto-orthodox Christians argued that Jesus Christ was both divine and human, that he was one being instead of two, and that he had taught his disciples the truth."[3] This view that he is "a unity of both divine and human" (the Hypostatic union) is opposed to both Adoptionism (that Jesus was only human and "adopted" by God, as the Ebionites believed), and Docetism (that Christ was only divine and merely seemed to be human, as the Marcionists believed), as well as Separationism (that an aeon had entered Jesus' body, which separated again from him during his death on the cross, as most Gnostics believed).[5]: 0:21

For Ehrman, in the canonical gospels, Jesus is characterized as a Jewish faith healer who ministered to the most despised people of the local culture. Reports of miracle working were not uncommon during an era "in the ancient world [where] most people believed in miracles, or at least in their possibility."[18]

Criticism

[edit]The traditional Christian view is that orthodoxy emerged to codify and defend the traditions inherited from the Apostles themselves. Hurtado argues that Ehrman's "proto-orthodox" Christianity was rooted into first-century Christianity:

...to a remarkable extent early-second-century protoorthodox devotion to Jesus represents a concern to preserve, respect, promote, and develop what were by then becoming traditional expressions of belief and reverence, and that had originated in earlier years of the Christian movement. That is, proto-orthodox faith tended to affirm and develop devotional and confessional tradition [...] Arland Hultgren[19] has shown that the roots of this appreciation of traditions of faith actually go back deeply and widely into first-century Christianity.[20]

Conversely, David Brakke argues that the "proto-orthodox" category tends to obscure the diversity of views among the very Christian thinkers and groups that are categorized as "proto-orthodox," sustaining an erroneous backward-looking view that a unified "proto-orthodox" viewpoint had existed from the early days of Christianity when no such unified group existed even in contrast with Ebionites, Marcionites, and Valentinian Christians:[21]

- This simple opposition obscures the diversity not only among proto-orthodoxy's others, but also among different representatives of the allegedly single proto-orthodox self. In several important respects, protoorthodox teachers, such as Justin Martyr and Clement of Alexandria, were more akin to Valentinus than to Irenaeus. Christian — and, for that matter, Jewish — self-differentiation in this period was always a multilateral affair and resulted in diverse forms of Christian thought and practice. The inclusion of these varied modes of Christian piety in the single category of 'orthodoxy' was in fact the achievement of the post-Constantinian imperial church and even then was never full or complete, but always partial and contested."

See also

[edit]- Apostolic Fathers

- Catholicism

- Chalcedonian Christianity

- Church Fathers

- Criticism of Christianity

- Diversity in early Christian theology

- Early Christianity

- Gnosticism

- Historical Jesus

- Miracles of Jesus

- Misquoting Jesus

- Nicene Christianity

- Orthodox Christianity

- Orthodoxy

- Paleo-orthodoxy

- Proto-Protestantism

- Seven Ecumenical Councils

- State church of the Roman Empire

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ O'Connor 1913.

- ^ Layton, Bentley (August 1, 1995). The Gnostic Scriptures: A New Translation with Annotations and Introductions. New York: Doubleday. p. 166. ISBN 978-0300140132.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2002). "2: Christians who would be Jews". Lost Christianities. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

One other term I need to define for our period, is made necessary by the circumstance that what I'm calling 'orthodoxy' is the point of view that became dominant in early Christianity, when I'm talking about Christianity before that view became dominant. In other words, calling somebody 'orthodox' in the 4th century makes sense, because by that time, Christians had decided what the dominant form of belief would be. But what do you call people who held that point of view, who held that belief, before it became dominant? I'm gonna use a term that scholars have come up with, which is simply 'proto-orthodoxy'. 'Proto-orthodoxy' refers to the set of beliefs that was going to become dominant in the 4th century, held by people before the 4th century.

- ^ a b c d e Bart D. Ehrman (2002). "19: The Rise Of Early Christian Orthodoxy". Lost Christianities. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 2018-07-06. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 136: "But only one form of Christianity, this group we have been calling proto-orthodox, emerged as victorious, and it is to this victory that we owe the most familiar features of what we think of today as Christianity. This victory bequeathed to us four Gospels to tell us virtually everything we know about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. In fact, it handed down to us the entire New Testament, twenty-seven books, the only books produced by Christians accepted as Scripture".

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 136: "In addition, the proto-orthodox victory conferred to Christian history a set... beliefs [that] include doctrines familiar to anyone conversant with Christianity: Christ as both divine and human, fully God and fully man. And the sacred Trinity, the three-in-one: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, three persons, but only one God, the mystery at the heart of traditional Christian faith".

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 137: "Bishop of Antioch at the beginning of the second century, Ignatius had been arrested, evidently for Christian activities, and sent to Rome for execution in the arena, where he was to be thrown to the wild beasts

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 137: "One of his letters is addressed to the Christians of Rome, in which he urges them not to intervene in the proceedings, because he is eager to be devoured by the wild beasts: By suffering that kind of death he will 'attain to God'.".

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 138: "Proto-orthodox authors considered this willingness to die for the faith one of the hallmarks of their religion, and in fact used it as a boundary marker, separating true believers (i.e., those who agreed with their theological perspectives) from the false 'heretics' they were so concerned about. Some of their opponents agreed that this was a distinctive boundary marker: One of the Gnostic tractates from Nag Hammadi, for example, The Testimony of Truth, takes just the opposite position, maintaining that martyrdom for the faith was ignorant and foolish. From this Gnostic perspective, a God who required a human sacrifice for himself would be completely vain (Test. Truth 31–37)."

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 141: "Ignatius was an avid and outspoken advocate of the monepiscopacy (single bishop). Each Christian community had a bishop, and this bishop's word was law. The bishop was to be followed as if he were God himself.

- ^ Ehrman 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Philippe Bobichon, "Millénarisme et orthodoxie dans les écrits de Justin Martyr" in Mélanges sur la question millénariste de l’Antiquité à nos jours, M. Dumont (dir.) [Bibliothèque d'étude des mondes chrétiens, 11], Paris, 2018, pp. 61-82 online copy ; Philippe Bobichon, "Préceptes éternels et Loi mosaïque dans le Dialogue avec Tryphon de Justin Martyr", Revue Biblique 3/2 (2004), pp. 238–254 online

- ^ Hopkins 2017, p. 457: But, per contra, it is extremely difficult for dispersed and prohibited house cult-groups and communities to maintain and enforce common beliefs and common liturgical practices across space and time in pre-industrial conditions of communications.43 The frequent claims that scattered Christian communities constituted a single Church was not a description of reality in the first two centuries AD, but a blatant yet forceful denial of reality. What was amazing was the persistence and power of the ideal in the face of its unachievability, even in the fourth century. On a local level, it is also unlikely that twenty households in a typical community, let alone a dozen households in a house cult-group, could maintain even one full-time, non-earning priest. Perhaps a group of forty households could, especially if they had a wealthy patron. But for most Christian communities of this size, a hierarchy of bishop and lesser clergy seems completely inappropriate.

- ^ Reid 1913: "So at the close of the first decade of the fifth century the entire Western Church was in possession of the full Canon of the New Testament. In the East, where, with the exception of the Edessene Syrian Church, approximate completeness had long obtained without the aid of formal enactments, opinions were still somewhat divided on the Apocalypse. But for the Catholic Church as a whole the content of the New Testament was definitely fixed, and the discussion closed".

- ^ From Letter XXXIX

- ^ McDonald & Sanders 2001, Appendix D-2, note 19: "Revelation was added later in 419 at the subsequent synod of Carthage".

- ^ Sanders 1996.

- ^ The rise of normative Christianity, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 495.

- ^ Brakke, David (2006). "Self-differentiation among Christian groups: the Gnostics and their opponents". In Mitchell, Margaret M; Young, Frances M (eds.). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 245–260. ISBN 9781139054836. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ehrman, Bart D. (2 October 2003), Lost Christianities: The Battle for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, New York: Oxford University Press (published 2003), ISBN 0-19-514183-0.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2015) [1996], The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0190203825.

- Henderson, John B. (1998). The Construction of Orthodoxy and Heresy: Neo-Confucian, Islamic, Jewish, and Early Christian Patterns. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791437599.

- Hopkins, Keith (2 November 2017). "12 - Christian Number and its implications". In Kelly, Christopher (ed.). Sociological Studies in Roman History. Cambridge University Press. p. 442. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139093552.014. ISBN 9781139093552.

- Hopkins, Keith; Kelly, Christopher (2018). "12 - Christian Number and its implications". Sociological Studies in Roman History. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge University Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-1-107-01891-4.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005), Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, William B Eerdmans

- McDonald, Lee Martin; Sanders, James A., eds. (2001), The Canon Debate, ISBN 1565635175

- O'Connor, John Bonaventure (1913). "St. Ignatius of Antioch". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Reid, George J. (1913). "Canon of the New Testament". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Sanders, E.P. (1996), The Historical Figure of Jesus, Penguin, ISBN 0140144994