Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity that is used to help predict similar flow patterns in different fluid flow situations. The concept was introduced by George Gabriel Stokes in 1851,[2] but the Reynolds number is named after Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912), who popularized its use in 1883.[3][4]

The Reynolds number is defined as the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces and consequently quantifies the relative importance of these two types of forces for given flow conditions.[5] Reynolds numbers frequently arise when performing scaling of fluid dynamics problems, and as such can be used to determine dynamic similitude between two different cases of fluid flow. They are also used to characterize different flow regimes within a similar fluid, such as laminar or turbulent flow:

- laminar flow occurs at low Reynolds numbers, where viscous forces are dominant, and is characterized by smooth, constant fluid motion;

- turbulent flow occurs at high Reynolds numbers and is dominated by inertial forces, which tend to produce chaotic eddies, vortices and other flow instabilities.

In practice, matching the Reynolds number is not on its own sufficient to guarantee similitude. Fluid flow is generally chaotic, and very small changes to shape and surface roughness can result in very different flows. Nevertheless, Reynolds numbers are a very important guide and are widely used.

Reynolds number interpretation has been extended into the area of arbitrary complex systems as well: financial flows,[6] nonlinear networks,[7] etc. In the latter case an artificial viscosity is reduced to nonlinear mechanism of energy distribution in complex network media. Reynolds number then represents a basic control parameter which expresses a balance between injected and dissipated energy flows for open boundary system. It has been shown [7] that Reynolds critical regime separates two types of phase space motion: accelerator (attractor) and decelerator. High Reynolds number leads to a chaotic regime transition only in frame of strange attractor model.

The Reynolds number can be defined for several different situations where a fluid is in relative motion to a surface.[n 1] These definitions generally include the fluid properties of density and viscosity, plus a velocity and a characteristic length or characteristic dimension. This dimension is a matter of convention – for example radius and diameter are equally valid to describe spheres or circles, but one is chosen by convention. For aircraft or ships, the length or width can be used. For flow in a pipe or a sphere moving in a fluid the internal diameter is generally used today. Other shapes such as rectangular pipes or non-spherical objects have an equivalent diameter defined. For fluids of variable density such as compressible gases or fluids of variable viscosity such as non-Newtonian fluids, special rules apply. The velocity may also be a matter of convention in some circumstances, notably stirred vessels. The Reynolds number is defined as[8]

where:

- v is the maximum[9] velocity of the object relative to the fluid (SI units: m/s)

- L is a characteristic linear dimension, (travelled length of the fluid; hydraulic diameter when dealing with river systems) (m)

- t denotes the time

- μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid (Pa·s or N·s/m2 or kg/(m·s))

- ν (nu) is the kinematic viscosity (ν = μ/ρ) (m2/s)

- ρ is the density of the fluid (kg/m3).

Note that multiplying the Reynolds number by Lv/Lv yields ρv2L2/μvL, which is the ratio of the inertial forces to the viscous forces.[10] It could also be considered the ratio of the total momentum transfer to the molecular momentum transfer.

Flow in pipe

For flow in a pipe or tube, the Reynolds number is generally defined as:[11]

where:

- DH is the hydraulic diameter of the pipe (the inside diameter if the pipe is circular) (m).

- Q is the volumetric flow rate (m3/s).

- A is the pipe's cross-sectional area (m2).

- v is the mean velocity of the fluid (m/s).

- μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid (Pa·s = N·s/m2 = kg/(m·s)).

- ν (nu) is the kinematic viscosity (ν = μ/ρ) (m2/s).

- ρ is the density of the fluid (kg/m3).

For shapes such as squares, rectangular or annular ducts where the height and width are comparable, the characteristical dimension for internal flow situations is taken to be the hydraulic diameter, DH, defined as:

where A is the cross-sectional area and P is the wetted perimeter. The wetted perimeter for a channel is the total perimeter of all channel walls that are in contact with the flow.[12] This means the length of the channel exposed to air is not included in the wetted perimeter.

For a circular pipe, the hydraulic diameter is exactly equal to the inside pipe diameter, D. That is,

For an annular duct, such as the outer channel in a tube-in-tube heat exchanger, the hydraulic diameter can be shown algebraically to reduce to

where

- Do is the inside diameter of the outside pipe, and

- Di is the outside diameter of the inside pipe.

For calculations involving flow in non-circular ducts, the hydraulic diameter can be substituted for the diameter of a circular duct, with reasonable accuracy, if the aspect ratio AR of the duct cross-section remains in the range 1/4 < AR < 4.[13]

Flow in a wide duct

For a fluid moving between two plane parallel surfaces—where the width is much greater than the space between the plates—then the characteristic dimension is equal to the distance between the plates.[13]

Flow in an open channel

For flow of liquid with a free surface, the hydraulic radius must be determined. This is the cross-sectional area of the channel divided by the wetted perimeter. For a semi-circular channel, it is half the radius. For a rectangular channel, the hydraulic radius is the cross-sectional area divided by the wetted perimeter. Some texts then use a characteristic dimension that is four times the hydraulic radius, chosen because it gives the same value of Re for the onset of turbulence as in pipe flow,[14] while others use the hydraulic radius as the characteristic length-scale with consequently different values of Re for transition and turbulent flow.

Flow around airfoils

Reynolds numbers are used in airfoil design to (among other things) manage "Scale Effect" when computing/comparing characteristics (a tiny wing, scaled to be huge, will perform differently).[15] Fluid dynamicists define the chord Reynolds number, R, like this: R = Vc/ν where V is the flight speed, c is the chord length, and ν is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid in which the airfoil operates, which is 1.460×10−5 m2/s for the atmosphere at sea level.[16] In some special studies a characteristic length other than chord may be used; rare is the "span Reynolds number" which is not to be confused with spanwise stations on a wing where chord is still used.[17]

Object in a fluid

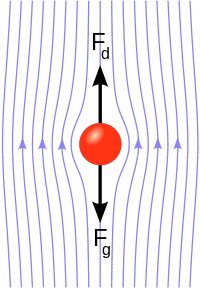

The Reynolds number for an object in a fluid, called the particle Reynolds number and often denoted Rep, is important when considering the nature of the surrounding flow, whether or not vortex shedding will occur, and its fall velocity.

In viscous fluids

Where the viscosity is naturally high, such as polymer solutions and polymer melts, flow is normally laminar. The Reynolds number is very small and Stokes' Law can be used to measure the viscosity of the fluid. Spheres are allowed to fall through the fluid and they reach the terminal velocity quickly, from which the viscosity can be determined.

The laminar flow of polymer solutions is exploited by animals such as fish and dolphins, who exude viscous solutions from their skin to aid flow over their bodies while swimming. It has been used in yacht racing by owners who want to gain a speed advantage by pumping a polymer solution such as low molecular weight polyoxyethylene in water, over the wetted surface of the hull.

It is, however, a problem for mixing of polymers, because turbulence is needed to distribute fine filler (for example) through the material. Inventions such as the "cavity transfer mixer" have been developed to produce multiple folds into a moving melt so as to improve mixing efficiency. The device can be fitted onto extruders to aid mixing.

Sphere in a fluid

For a sphere in a fluid, the characteristic length-scale is the diameter of the sphere and the characteristic velocity is that of the sphere relative to the fluid some distance away from the sphere, such that the motion of the sphere does not disturb that reference parcel of fluid. The density and viscosity are those belonging to the fluid.[18] Note that purely laminar flow only exists up to Re = 10 under this definition.

Under the condition of low Re, the relationship between force and speed of motion is given by Stokes' law.[19]

Oblong object in a fluid

The equation for an oblong object is identical to that of a sphere, with the object being approximated as an ellipsoid and the axis of length being chosen as the characteristic length scale. Such considerations are important in natural streams, for example, where there are few perfectly spherical grains. For grains in which measurement of each axis is impractical, sieve diameters are used instead as the characteristic particle length-scale. Both approximations alter the values of the critical Reynolds number.

Fall velocity

The particle Reynolds number is important in determining the fall velocity of a particle. When the particle Reynolds number indicates laminar flow, Stokes' law can be used to calculate its fall velocity. When the particle Reynolds number indicates turbulent flow, a turbulent drag law must be constructed to model the appropriate settling velocity.

Packed bed

For fluid flow through a bed, of approximately spherical particles of diameter D in contact, if the "voidage" is ε and the "superficial velocity" is vs, the Reynolds number can be defined as:[20]

or

or

The choice of equation depends on the system involved: the first is successful in correlating the data for various types of packed and fludized beds, the second Reynolds number suits for the liquid-phase data, while the third was found successful in correlating the fludized bed data, being first introduced for liquid fluidized bed system.[20]

Laminar conditions apply up to Re = 10, fully turbulent from Re = 2000.[18]

Stirred vessel

In a cylindrical vessel stirred by a central rotating paddle, turbine or propeller, the characteristic dimension is the diameter of the agitator D. The velocity V is ND where N is the rotational speed. Then the Reynolds number is:

The system is fully turbulent for values of Re above 10000.[21]

Transition and turbulent flow

In boundary layer flow over a flat plate, experiments confirm that, after a certain length of flow, a laminar boundary layer will become unstable and turbulent. This instability occurs across different scales and with different fluids, usually when Rex ≈ 5×105,[22] where x is the distance from the leading edge of the flat plate, and the flow velocity is the freestream velocity of the fluid outside the boundary layer.

For flow in a pipe of diameter D, experimental observations show that for "fully developed" flow,[n 2] laminar flow occurs when ReD < 2300 and turbulent flow occurs when ReD > 4000.[23] In the interval between 2300 and 4000, laminar and turbulent flows are possible and are called "transition" flows, depending on other factors, such as pipe roughness and flow uniformity. This result is generalized to non-circular channels using the hydraulic diameter, allowing a transition Reynolds number to be calculated for other shapes of channel.

These transition Reynolds numbers are also called critical Reynolds numbers, and were studied by Osborne Reynolds around 1895.[4] The critical Reynolds number is different for every geometry.[24]

Pipe friction

Pressure drops seen for fully developed flow of fluids through pipes can be predicted using the Moody diagram which plots the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor f against Reynolds number Re and relative roughness ε/D. The diagram clearly shows the laminar, transition, and turbulent flow regimes as Reynolds number increases. The nature of pipe flow is strongly dependent on whether the flow is laminar or turbulent.

Similarity of flows

In order for two flows to be similar they must have the same geometry, and have equal Reynolds numbers and Euler numbers. When comparing fluid behavior at corresponding points in a model and a full-scale flow, the following holds:

quantities marked with m concern the flow around the model and the others the actual flow. This allows engineers to perform experiments with reduced models in water channels or wind tunnels, and correlate the data to the actual flows, saving on costs during experimentation and on lab time. Note that true dynamic similitude may require matching other dimensionless numbers as well, such as the Mach number used in compressible flows, or the Froude number that governs open-channel flows. Some flows involve more dimensionless parameters than can be practically satisfied with the available apparatus and fluids, so one is forced to decide which parameters are most important. For experimental flow modeling to be useful, it requires a fair amount of experience and judgement of the engineer.

An example where the mere Reynolds number is not sufficient for similarity of flows (or even the flow regime – laminar or turbulent) are bounded flows, i.e. flows that are restricted by walls or other boundaries. A classical example of this is the Taylor–Couette flow, where the dimensionless ratio of radii of bounding cylinders is also important, and many technical applications where these distinctions play an important role.[25][26] Principles of these restrictions were developed by Maurice Marie Alfred Couette and Geoffrey Ingram Taylor and developed further by Floris Takens and David Ruelle.

- Ciliate ~ 1 x 10−1

- Smallest Fish ~ 1

- Blood flow in brain ~ 1 × 102

- Blood flow in aorta ~ 1 × 103

Onset of turbulent flow ~ 2.3 × 103 to 5.0 × 104 for pipe flow to 106 for boundary layers

- Typical pitch in Major League Baseball ~ 2 × 105

- Person swimming ~ 4 × 106

- Fastest Fish ~ 1 x 106

- Blue Whale ~ 3 × 108

- A large ship (RMS Queen Elizabeth 2) ~ 5 × 109

Smallest scales of turbulent motion

In a turbulent flow, there is a range of scales of the time-varying fluid motion. The size of the largest scales of fluid motion (sometimes called eddies) are set by the overall geometry of the flow. For instance, in an industrial smoke stack, the largest scales of fluid motion are as big as the diameter of the stack itself. The size of the smallest scales is set by the Reynolds number. As the Reynolds number increases, smaller and smaller scales of the flow are visible. In a smoke stack, the smoke may appear to have many very small velocity perturbations or eddies, in addition to large bulky eddies. In this sense, the Reynolds number is an indicator of the range of scales in the flow. The higher the Reynolds number, the greater the range of scales. The largest eddies will always be the same size; the smallest eddies are determined by the Reynolds number.

What is the explanation for this phenomenon? A large Reynolds number indicates that viscous forces are not important at large scales of the flow. With a strong predominance of inertial forces over viscous forces, the largest scales of fluid motion are undamped—there is not enough viscosity to dissipate their motions. The kinetic energy must "cascade" from these large scales to progressively smaller scales until a level is reached for which the scale is small enough for viscosity to become important (that is, viscous forces become of the order of inertial ones). It is at these small scales where the dissipation of energy by viscous action finally takes place. The Reynolds number indicates at what scale this viscous dissipation occurs.

In physiology

Poiseuille's law on blood circulation in the body is dependent on laminar flow. In turbulent flow the flow rate is proportional to the square root of the pressure gradient, as opposed to its direct proportionality to pressure gradient in laminar flow.

Using the definition of the Reynolds number we can see that a large diameter with rapid flow, where the density of the blood is high, tends towards turbulence. Rapid changes in vessel diameter may lead to turbulent flow, for instance when a narrower vessel widens to a larger one. Furthermore, a bulge of atheroma may be the cause of turbulent flow, where audible turbulence may be detected with a stethoscope.

Derivation

The Reynolds number can be obtained when one uses the nondimensional form of the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations for a newtonian fluid expressed in terms of the Lagrangian derivative:

Each term in the above equation has the units of a "body force" (force per unit volume) with the same dimensions of a density times an acceleration. Each term is thus dependent on the exact measurements of a flow. When one renders the equation nondimensional, that is when we multiply it by a factor with inverse units of the base equation, we obtain a form which does not depend directly on the physical sizes. One possible way to obtain a nondimensional equation is to multiply the whole equation by the following factor:

where:

- V is the mean velocity, v or v, relative to the fluid (m/s).

- L is the characteristic length (m).

- ρ is the fluid density (kg/m3).

If we now set:

we can rewrite the Navier–Stokes equation without dimensions:

where the term μ/ρLV = 1/Re.

Finally, dropping the primes for ease of reading:

This is why mathematically all Newtonian, incompressible flows with the same Reynolds number are comparable. Notice also, in the above equation, as Re → ∞ the viscous terms vanish. Thus, high Reynolds number flows are approximately inviscid in the free-stream.

Relationship to other dimensionless parameters

There are many dimensionless numbers in fluid mechanics. The Reynolds number measures the ratio of advection and diffusion effects on structures in the velocity field, and is therefore closely related to Péclet numbers, which measure the ratio of these effects on other fields carried by the flow, for example temperature and magnetic fields. Replacement of the kinematic viscosity ν = μ/ρ in Re by the thermal or magnetic diffusivity results in respectively the thermal Péclet number and the magnetic Reynolds number. These are therefore related to Re by products with ratios of diffusivities, namely the Prandtl number and magnetic Prandtl number.

See also

Notes

- ^ The definition of the Reynolds number is not to be confused with the Reynolds equation or lubrication equation.

- ^ Full development of the flow occurs as the flow enters the pipe, the boundary layer thickens and then stabilizes after several diameters distance into the pipe.

References

- ^ Tansley, Claire E.; Marshall, David P. (2001). "Flow past a Cylinder on a Plane, with Application to Gulf Stream Separation and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current" (PDF). Journal of Physical Oceanography. 31 (11): 3274–3283. Bibcode:2001JPO....31.3274T. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2001)031<3274:FPACOA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Stokes, George (1851). "On the Effect of the Internal Friction of Fluids on the Motion of Pendulums". Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 9: 8–106. Bibcode:1851TCaPS...9....8S.

- ^ Reynolds, Osborne (1883). "An experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 174 (0): 935–982. doi:10.1098/rstl.1883.0029. JSTOR 109431.

- ^ a b Rott, N. (1990). "Note on the history of the Reynolds number". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 22 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:1990AnRFM..22....1R. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.22.010190.000245.

- ^ Falkovich, G. (2011). Fluid Mechanics. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Los, C. (2003). Financial Market Risk: Measurement and Analysis. Routledge.

- ^ a b Kamenshchikov, Sergey (2013). "Extended Prigogine Theorem: Method for Universal Characterization of Complex System Evolution". Chaos and Complexity Letters. 8 (1): 63–71.

- ^ Reynolds Number

- ^ Bird R.B., Stewart W.E., Lightfoot E.N. Transport phenomena

- ^ Batchelor, G. K. (1967). An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–215.

- ^ "Reynolds Number". Engineeringtoolbox.com.

- ^ Holman, J. P. Heat Transfer. McGraw Hill.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Fox, R. W.; McDonald, A. T.; Pritchard, Phillip J. (2004). Introduction to Fluid Mechanics (6th ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. p. 348. ISBN 0-471-20231-2.

- ^ Streeter, V. L. (1962). Fluid Mechanics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ^ P. B. S. Lissaman (1983). "Low-Reynolds-Number Airfoils,". Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. (15): 223–39. Bibcode:1983AnRFM..15..223L. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.15.010183.001255.

- ^ ISO. "International Standard Atmosphere". eng.cam.ac.uk.

- ^ Uwe Ehrenstein; Christophe Eloy. "Skin friction on a moving wall and its implications for swimming animals" (PDF). Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ a b Rhodes, M. (1989). Introduction to Particle Technology. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-98482-5.

- ^ Dusenbery, David B. (2009). Living at Micro Scale. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ a b Dwivedi, P. N. (1977). "Particle-fluid mass transfer in fixed and fluidized beds". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Process Design and Development. 16 (2): 157–165. doi:10.1021/i260062a001.

- ^ Sinnott, R. K. Coulson & Richardson's Chemical Engineering, Volume 6: Chemical Engineering Design (4th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 73. ISBN 0-7506-6538-6.

- ^ De Witt, D. P. (1990). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer. New York: Wiley.

- ^ Holman, J. P. (2002). Heat Transfer. McGraw-Hill. p. 207.

- ^ Shih, Merle C. Potter, Michigan State University, David C. Wiggert, Michigan State University, Bassem Ramadan, Kettering University ; with Tom I-P. (2012). Mechanics of fluids (Fourth edition. ed.). p. 105. ISBN 978-0-495-66773-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ restricted flow in industry application

- ^ article about flow restrictions

- ^ Patel, V. C.; Rodi, W.; Scheuerer, G. (1985). "Turbulence Models for Near-Wall and Low Reynolds Number Flows—A Review". AIAA Journal. 23 (9): 1308–1319. Bibcode:1985AIAAJ..23.1308P. doi:10.2514/3.9086.

- ^ Dusenbery, David B. (2009). Living at Micro Scale. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780674031166.

Further reading

- Zagarola, M. V. and Smits, A. J., "Experiments in High Reynolds Number Turbulent Pipe Flow." AIAA paper #96-0654, 34th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno, Nevada, January 15–18, 1996.

- Jermy M., "Fluid Mechanics A Course Reader," Mechanical Engineering Dept., University of Canterbury, 2005, pp. d5.10.

- Hughes, Roger "Civil Engineering Hydraulics," Civil and Environmental Dept., University of Melbourne 1997, pp. 107–152

- Fouz, Infaz "Fluid Mechanics," Mechanical Engineering Dept., University of Oxford, 2001, p. 96

- E. M. Purcell. "Life at Low Reynolds Number", American Journal of Physics vol 45, pp. 3–11 (1977)[1]

- Truskey, G. A., Yuan, F, Katz, D. F. (2004). Transport Phenomena in Biological Systems Prentice Hall, pp. 7. ISBN 0-13-042204-5. ISBN 978-0-13-042204-0.

External links

- The Reynolds Number at Sixty Symbols