Richard Wainwright (admiral)

Richard Wainwright | |

|---|---|

Richard Wainwright in 1902 | |

| Born | December 17, 1849 Washington, D.C. |

| Died | March 6, 1926 (aged 76) Washington, D.C. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1868–1911 |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands | Office of Naval Intelligence USS Gloucester 2nd Division, Great White Fleet |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Relations | Son of Cmdr. Richard Wainwright Father of Cmdr. Richard Wainwright |

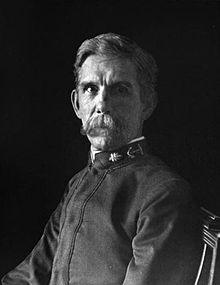

Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright (17 December 1849 – 6 March 1926), son of Commander Richard Wainwright, was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish–American War.

Biography

Early life and ancestors

Born in Washington, D.C., the son of Sarah Franklin Bache and Richard Wainwright. He was the grandson of Richard Bache, Jr., who served in the Republic of Texas Navy and was elected as a Representative to the Second Texas Legislature in 1847 and Sophia Burrell Dallas, the daughter of Arabella Maria Smith and Alexander J. Dallas an American statesman who served as the U.S. Treasury Secretary under President James Madison. He was great-grandson of Sarah Franklin Bache and Richard Bache, the great-great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, and a nephew of George Mifflin Dallas the 11th Vice President of the United States who served under James K. Polk.[1]

Early career

Wainwright was appointed to the US Naval Academy in 1864 by President Abraham Lincoln and graduated near the top of his class in 1868. Wainwright's early career is not well documented. From 1890 to 1893 he commanded the Alert, and in 1896 he became the Chief Intelligence Officer of the Navy. In November 1897, he was ordered to the Armored Cruiser Maine, to serve as executive officer under Captain Charles D. Sigsbee.[2][3]

Spanish–American War

On the night the Maine was blown up in Havana harbor, Wainwright stood beside Sigsbee on the quarterdeck as the vessel was sinking. It was Wainwright who issued the order to lower the lifeboats in which the surviving crew escaped. From the beginning, Wainwright believed the Maine was not blown up by accident and he was impatient to avenge the death of the officers, bluejackets and Marines who died as a result.

In the interval between the blowing up of the Maine and the declaration of war against Spain, Wainwright was assigned command of the tender Fern and placed in charge of the salvage survey and recovery of the bodies of the victims.[4][5] He stayed aboard throughout the seven weeks long Sampson court of inquiry, never setting foot in ashore. As the initial salvage closed, for concern about oncoming war, Wainwright remained. On the day that the last salvage team was ordered home, the Spanish naval commander in Havana, Admiral Vincente Manterola, ordered the American flag, which was still flying from the rigging of the wrecked Maine, struck. Wainwright heard of the order and, calling an interpreter, issued an order that immediately made him famous,[2]

Tell the officer in charge of the guard that if any Spaniard touches the flag that flies from that wreck, there will be another wreck in Havana harbor. Tell him I will sink his barge myself if he attempts to carry out that order.

When Wainwright did finally leave Havana, he hauled down the flag himself. On his arrival in Washington, the U. S. Navy was in the process of purchasing vessels that could be used in the war. Among them was a yacht, the Corsair, owned by J. P. Morgan. She was converted into a gunboat, renamed the Gloucester, and commissioned with Wainwright in command. In the Battle of Santiago de Cuba he engaged the Spanish torpedo boats Furor and Plutón, driving them ashore as wrecks with her battery of 6-pounders.[6] The victory came with no casualties, which was attributed to "The accuracy and rapidity of her fire, making the proper service of the guns on the Spanish ships impossible." Wainwright was commended for his valor in this action.[2][7]

After ordering his heavily damaged flagship Infanta Maria Teresa to run aground, Spanish fleet commander Spanish Admiral Cervera, was picked up by the Gloucester. Wainwright was there to greet him as he was brought aboard. "I congratulate you, sir," said the American, "on having made as gallant a fight as was ever seen on the sea."[2]

1900-1911

From 1900–1902, Wainwright was Superintendent of United States Naval Academy. During this time, the submarine boat Holland was in Annapolis to train crews for submarines then under construction.[8] Wainwright, having this opportunity to observe their operation, fully endorsed them for their planned harbor defense role.[9]

In 1904 he commanded American forces during the Santo Domingo Affair in which his ships shelled rebel troops and supported an amphibious assault. Later, promoted to rear admiral, he commanded the Second Division of the Great White Fleet during that fleet's historic voyage around the world from 1907-1909.[4]

Retired from active duty on December 7, 1911. Admiral Wainwright died on March 6, 1926 in Washington, D.C.[10]

Marriage and family

He married on September 11, 1873 at Washington, D.C., Evelyn Wotherspoon, born June 13, 1853 at Washington, D.C., and died on November 24, 1937 at Washington, D.C.[10] Their son, Richard Wainwright, Jr., Commander, United States Navy, earned the Medal of Honor for his service at Veracruz, Mexico, and is also buried in the cemetery at the United States Naval Academy.

A Naval Academy classmate, Admiral Seaton Schroeder, became his brother-in-law when he married Wainwright's sister,[2] Maria Campbell Bache Wainwright.

Namesakes

Three ships have been named USS Wainwright for Richard, his father, his son and two cousins.

Gallery

See also

References

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- ^ "Descendants of Signers of the Declaration of Independence". Evening star. Washington, D.C. 2 July 1911. p. 6 (Part 4). Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Wainwright to Leave the Navy". The Princeton Union. Princeton, Minnesota. 21 December 1911. p. 10. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Fighting Dick Wainwright on Navy Retired List". The Washington Herald. Washington, D.C. 17 December 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Wainwright". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "The Wrecked Maine: Board of Survey Will Determine Her Final Disposition". The Salt Lake Herald. Salt Lake City, Utah. 28 March 1898. p. 2. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "Armed Yacht vs. Torpedo-Boat Destroyers". Marine Engineering. 2 (August 1898). Marine Publishing Company: 15. 1898. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Gloucester (Gbt) i". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "The Holland Off for Annapolis". New-York Tribune. New York, NY. October 20, 1900. p. 6. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Submarine Boats for Harbor Defense". The St. Louis Republic. St. Louis, Missouri. June 11, 1902. p. 8. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ a b Richard Wainwright at Find a Grave

External links

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Wainwright, Richard, RADM, Togetherweserved.com