Riken

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Riken (理研) is a large research institute in Japan. Founded in 1917, it now has about 3,000 scientists on seven campuses across Japan, the main one in Wakō, just outside Tokyo. Riken is a Designated National Research and Development Institute[1] (formerly an Independent Administrative Institution) whose formal name in Japanese is Rikagaku Kenkyūsho (理化学研究所), and its full name in Japanese is Kokuritsu Kenkyū Kaihatsu Hōjin Rikagaku Kenkyūsho (国立研究開発法人理化学研究所).

Riken conducts research in many areas of science, including physics, chemistry, biology, medical science, engineering, high-performance computing and computational science, and ranging from basic research to practical applications. It is almost entirely funded by the Japanese government, and its annual budget is about ¥88 billion (US$760 million).[when?]

History

In 1913, the well-known scientist Jokichi Takamine first proposed the establishment of a national science research institute in Japan. This task was taken on by Viscount Shibusawa Eiichi, a prominent businessman, and following a resolution by the Diet in 1915, Riken came into existence in March 1917. In its first incarnation, Riken was a private foundation (zaidan), funded by a combination of industry, the government, and the Imperial Household. It was located in the Komagome district of Tokyo, and its first Director was the mathematician Baron Dairoku Kikuchi.

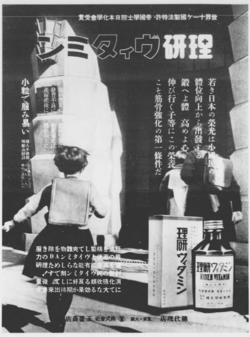

In 1927, Viscount Masatoshi Ōkōchi, the third Director, established the Riken Konzern (a zaibatsu). This was a group of spin-off companies that used Riken's scientific achievements for commercial ends and returned the profits to Riken. At its peak in 1939 the Konzern comprised about 121 factories and 63 companies, including Riken Kankōshi, which is now Ricoh.

During World War II the Japanese army's atomic bomb program was conducted at Riken. In April 1945 the US bombed Riken's laboratories in Komagome, and in November, after the end of the war, Allied soldiers destroyed its two cyclotrons.

After the war, the Allies dissolved Riken as a private foundation, and it was brought back to life as a company called Kagaku Kenkyūsho (科学研究所), or Kaken (科研). In 1958 the Diet passed the Riken Law, whereby the institute returned to its original name and entered its third incarnation, as a public corporation (特殊法人, tokushu hōjin), funded by the government. In 1963 it relocated to a large site in Wakō in Saitama Prefecture, just outside Tokyo.

Since the 1980s Riken has expanded dramatically. New labs, centers, and institutes have been established in Japan and overseas, including:

- in 1984, the Life Science Center in Tsukuba

- in 1995, the Muon Research Facility at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK

- in 1997, the Harima Institute, the Brain Science Institute in Wako, and the center at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in the USA

- in 1998, the Genomic Sciences Center

- in 2000, the Yokohama Institute, which now contains four centers for research in the life sciences

- in 2002, the Kobe Institute, which contains the Center for Developmental Biology

In October 2003, Riken's status changed again, to Independent Administrative Institution. As such, Riken is still publicly funded, and it is periodically evaluated by the government, but it has a higher degree of autonomy than before.

Riken is regarded as the flagship research institute in Japan. It conducts basic and applied experimental research in a wide range of science and technology fields including physics, chemistry, medical science, biology and engineering. In the wake of the 2014 Stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency cell controversy, observers, journalists, and former members of Riken have stated that the organization is riddled with unprofessional and inadequate scientific rigor and consistency, and that this is reflective of serious issues with scientific research in Japan in general.[2][3]

Organizational structure

The main divisions of Riken are listed here. Purely administrative divisions are omitted.

- Headquarters (mostly in Wako)

- Wako Branch

- Center for Emergent Matter Science (research on new materials for reduced power consumption)

- Center for Sustainable Resource Science (research toward a sustainable society)

- Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science (site of the Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory, a heavy-ion accelerator complex)

- Brain Science Institute

- Center for Advanced Photonics (research on photonics including terahertz radiation)

- Research Cluster for Innovation

- Global Research Cluster

- Tsukuba Branch

- BioResource Center

- Harima Institute

- Riken SPring-8 Center (site of the SPring-8 synchrotron and the SACLA x-ray free electron laser)

- Yokohama Branch (site of the Yokohama Nuclear magnetic resonance facility)

- Center for Sustainable Resource Science

- Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (research toward personalized medicine)

- Center for Life Science Technologies (also based in Kobe)

- Program for Drug Discovery and Medical Technology Platform

- Structural Biology Laboratory

- Sugiyama Laboratory

- Kobe Branch

- Center for Developmental Biology (developmental biology and nuclear medicine medical imaging techniques)

- Quantitative Biology Center (in Osaka)

- Advanced Institute for Computational Science (AICS, home of the K computer and The post-K computer development plan)

- Center for Life Science Technologies

Facts and achievements

- Two Riken scientists have won the Nobel prize for physics: Hideki Yukawa in 1949 and Sin'ichirō Tomonaga in 1965.

- The SPring-8 (Super Photon Ring 8GeV) facility in Harima is the world's largest and most powerful third-generation synchrotron radiation facility.[4]

- In July 2004 a team at Riken created element 113. On April 2, 2005 the same team successfully created it for the second time, and a third event was seen in 2012. The discovery was officially recognized by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) in December 2015.[5][6]

- The Riken Super Combined Cluster is one of the world's fastest supercomputers. In January 2006, Riken set up the Next-Generation Supercomputer R&D Center, with the purpose of designing and building the fastest supercomputer in the world, and in June 2006, it announced the completion of a one-petaFLOPS computer system designed specially for molecular dynamics simulation. Currently a new system, the K computer is being installed at Riken and despite it being still not finished, it topped the LINPACK benchmark with the performance of 8.162 petaFLOPS, or 8.162 quadrillion calculations per second, with a computing efficiency ratio of 93.0%, making it the fastest supercomputer in the world.[7][8][9][10] The complete project entered service in November 2012.[11]

Name

The full Japanese name of Riken is Rikagaku Kenkyūsho (理化学研究所), which means "The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research" (though it now also conducts research in biology and other fields). Riken (理研) is a Japanese abbreviation of this.

"Riken" is pronounced as a single word: /ˈrɪkɛn/ (RI-ken). The full Japanese name, "Rikagaku Kenkyūsho", is sometimes pronounced "Rikagaku Kenkyūjo", which may be used less often but is not incorrect as it is merely an example of rendaku.

List of presidents

- Dairoku Kikuchi (1917)

- Furuichi Kōi (1917-1921)

- Masatoshi Ōkōchi (1921-1946)

- Yoshio Nishina (1946-1951)

- Kiichi Sakatani (1951-1952)

- Takeshi Murayama (1952-1956)

- Masanori Satō (1956-1958)

- Haruo Nagaoka (1958–1966)

- Shirō Akahori (1966–1970)

- Toshio Hoshino (1970-1975)

- Shinji Fukui (1975–1980)

- Tatsuoki Miyajima (1980–1988)

- Minoru Oda (1988–1993)

- Akito Arima (1993–1998)

- Shunichi Kobayashi (1998–2003)

- Ryōji Noyori (2003 – 31 March 2015)

- Hiroshi Matsumoto (1 April 2015 – present)[12]

Notable scientists and other people from Riken

- Kotaro Honda, inventor of KS steel

- Kikunae Ikeda, discoverer of monosodium glutamate and the umami flavor

- Dairoku Kikuchi, mathematician and the first Director of Riken

- Seishi Kikuchi, physicist, known for his explanation of the Kikuchi lines

- Hiroaki Kitano systems biologist involved in RoboCup, AIBO etc.[13]

- Chika Kuroda, chemist, known for research on natural dyes, and one of the first three women to receive a bachelor's degree in Japan

- Daniel Loss, physicist, known for proposing the Loss–DiVincenzo quantum computer

- Kosuke Morita, physicist, leader of team that discovered element 113

- Hantaro Nagaoka, postulator of the Saturnian model of the atom

- Ukichiro Nakaya, physicist and essayist

- Yoshio Nishina, leading atomic physicist who worked with Bohr, Einstein, Heisenberg and Dirac

- Ryōji Noyori, past President, and winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2001

- Masatoshi Ōkōchi, physicist and the third Director of Riken

- Yoshiki Sasai, developmental biologist who grew an optic cup from stem cells.

- Umetaro Suzuki, discoverer of vitamin B1

- Toshio Takamine, specialist in spectroscopy, author of The "Near Infra-Red Spectra of Helium and Mercury" and "Absorption of Ha Line" and "The structure of mercury lines examined by an echelon grating and a Lummer-Gehrcke plate"

- Masatoshi Takeichi, discoverer of the cadherin family of cell-cell adhesion molecules and head of the Riken Center for Developmental Biology

- Ume Tange, researcher on vitamins, and one of first three women to receive a bachelor's degree in Japan

- Torahiko Terada, physicist and essayist

- Yoshinori Tokura, pioneer of strongly-correlated electron systems in Japan.

- Shin'ichirō Tomonaga, winner of the 1965 Nobel physics prize for his work on quantum electrodynamics

- Susumu Tonegawa, head of the Brain Science Institute and winner of the 1987 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the mechanism of antibody diversity.

- Michiyo Tsujimura, biochemist, known for isolating components of green tea

- Tadashi Watanabe, head of Riken's Next-Generation Supercomputer R&D Center

- Toshiko Yuasa, Japan's first female physicist, who specialized in nuclear physics

- Hideki Yukawa, physicist who won the 1949 Nobel prize for his prediction of the pion

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "MEXT" (PDF).

- ^ Otake, Tomoko, "'STAPgate' shows Japan must get back to basics in science", Japan Times, 21 April 2014

- ^ Schreiber, Mark, "Ongoing Obokata story seeks out scandal", Japan Times, 5 July 2014, p. 19

- ^ Futura-Sciences. "Record : un laser X avec une longueur d'onde de 1,2 angström". Futura-Sciences. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ "Search for element 113 concluded at last". www.sciencecodex.com. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ "Discovery Of Element 113 By RIKEN Scientists Completes 7th Row Of Periodic Table". Tech Times. 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ "Japanese 'K' Computer Is Ranked Most Powerful". The New York Times. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ "Japan Reclaims Top Ranking on Latest TOP500 List of World's Supercomputers", top500.org, retrieved June 20, 2011

- ^ "K computer, SPARC64 VIIIfx 2.0GHz, Tofu interconnect", top500.org, retrieved June 20, 2011

- ^ "Supercomputer "K computer" Takes First Place in World". RIKEN. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ "With 16 petaflops and 1.6M cores, DOE supercomputer is world's fastest". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- ^ Hiroshi Matsumoto takes helm at Riken, retrieved 7 April 2015

- ^ Kitano, H.; Asada, M.; Kuniyoshi, Y.; Noda, I.; Osawa, E. (1997). "Robo Cup". Proceedings of the first international conference on Autonomous agents - AGENTS '97. p. 340. doi:10.1145/267658.267738. ISBN 0897918770.

External links

- Riken official website (in English and Japanese) – this official website is the source for all of the information in this article

- Riken Research (English and Japanese) – A resource for up-to-date information on key achievements of Riken researchers.