Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1867 – May 16, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Ira Harris |

| Succeeded by | Elbridge Lapham |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 21st district | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1867 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Kernan |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Bailey |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 20th district | |

| In office March 4, 1859 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | Orsamus Matteson |

| Succeeded by | Ambrose Clark |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 30, 1829 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 18, 1888 (aged 58) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (Before 1854) Republican (1854–1888) |

| Other political affiliations | Stalwart Republican |

| Spouse | Julia Catherine Seymour |

| Signature |  |

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829 – April 18, 1888) was a politician from New York who served both as a member of the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He was the leader of the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party, the first Republican senator from New York to be elected for three terms, and the last person to turn down a U.S. Supreme Court appointment after he had already been confirmed to the post by the U.S. Senate. While in the House, Representative Conkling served as body guard for Representative Thaddeus Stevens, a sharp-tongued anti slavery representative, and fully supported the Republican War effort.[1] Conkling, who was temperate and detested tobacco, was known for being a body builder through regularly exercising and boxing.[1] Conkling was elected to the Senate in 1867 as a leading Radical, who supported the rights of African Americans during Reconstruction.[1]

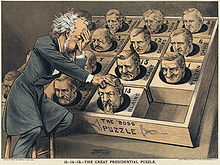

As leader of the Stalwarts, Conkling controlled patronage at the New York Customs House. Although Senator Conkling was supported by President Ulysses S. Grant, Conkling did not support Grant's Civil Service Commission reform initiative. Conkling also refused to accept Grant's nomination of him as Chief Justice of the United States, believing his talents belonged in the Senate.[1] The control over patronage led to a bitter conflict between Senator Conkling and President Rutherford B. Hayes.[1] Conkling also opposed Hayes' appointment of William M. Evarts as Secretary of State.[1] Conkling publicly led opposition to President Hayes' attempt to administer Civil Service Reform at the New York Customs House. In 1880, Conkling supported Ulysses S. Grant for President; however, James A. Garfield was nominated and elected President. Conkling's conflict with President Garfield over New York Customs House patronage led to his resignation from the Senate in May 1881. After Garfield's assassination in 1881, Vice President Chester A. Arthur became President. When President Arthur offered his friend Conkling an associate justiceship on the Supreme Court, Conkling accepted the offer and was approved by the Senate. However, Conkling later changed his mind and refused to serve.[2] He practiced law in New York until his death in 1888.[2]

Early life

Conkling was born on October 30, 1829 in Albany, New York to Alfred Conkling, a U.S. Representative and federal judge and his wife Eliza Cockburn (cousin of the late Lord Chief-Justice Sir Alexander Cockburn of England).[3] Raised in an atmosphere of law and politics, early associations with notable figures of the day (including former presidents Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams) left an impression on young Roscoe. However, described by his father as "utterly untutored" and a "romping boy," Roscoe (age thirteen at the time) was left in the care of Professor George W. Clarke at the Mount Washington Collegiate Institute in New York City so that he may "be trained to studious habits." [4] While constantly referring to a 1787 British textbook titled "The Art of Speaking," which emphasized the importance of facial action and gesture, Roscoe and his older brother took lessons in diction from an English professor named Harvey and delivered speeches to each other for practice's sake. Roscoe then entered the Auburn Academy in 1843, where he remained for three years.[5]

Even as a schoolboy, Roscoe's intimidating appearance and intellect demanded attention. As a childhood friend describes him, young Roscoe was "as large and massive in his mind as he was in his frame, and accomplished in his studies precisely what he did in his social life — a mastery and command which his companions yielded to him as due."[6] At the age of seventeen, Roscoe opted to forego a college education in favor of studying law under Joshua A. Spencer and Francis Kernan in Utica, New York. Roscoe immediately made an impression upon his preceptors. When asked to supply a Whig orator who could stand up to Democratic bullies at a local village meeting, Spencer's response was "I shall send Mr. Conkling; I think he will make himself heard." [7] Quickly integrating himself into the "society" in Utica, Roscoe certainly made himself heard on a variety of issues, especially those concerning human rights. For example, though only eighteen at the time, Roscoe's deep sympathy for the sufferers of the Great Famine in Ireland led him to speak on behalf of victims of starvation at various venues in Central New York. Additionally, as Theodore M. Pomeroy recalls, even fifteen years before the Civil War Roscoe displayed a deep abhorrence for slavery, or as he described it, "man's inhumanity to man." [8] He married Julia Catherine Seymour, sister of the Democratic politician and Governor of New York Horatio Seymour. His first political endeavor came in 1848, when he made campaign speeches on behalf of Taylor and Fillmore. He was admitted to the bar in 1850, and in the same year became district attorney of Oneida County by appointment of Governor Fish.[9]

In 1852 he returned to Utica, where in the next few years he established a reputation as a lawyer of ability. Up to 1852, in which year he stumped New York State for General Winfield Scott, the Whig candidate for the presidency, Conkling was identified with the Whig Party, but in the movement that resulted in the organization of the Republican Party he took an active part, and his work, both as a political manager and an orator, contributed largely toward carrying New York in 1856 for Frémont and Dayton, the Republican nominees.

Elected office holder

Conkling was elected Mayor of Utica in 1858, and then elected as a Republican to the 36th and 37th United States Congresses, holding office from March 4, 1859, to March 3, 1863. He was Chairman of the U.S. House Committee on the District of Columbia (37th Congress). He refused to follow the financial policy of his party in 1862, and delivered a notable speech against the passage of the Legal Tender Act, which made a certain class of treasury notes receivable for all public and private debts. In this opposition he was joined by his brother, Frederick Augustus Conkling, at that time also a Republican member of Congress. That year he was defeated for re-election by Democrat Francis Kernan.

From 1863 to 1865, he acted as a judge advocate of the War Department, investigating alleged frauds in the recruiting service in western New York. In 1864, two years after his defeat by Kernan, Conkling defeated Kernan for re-election, and served in the 39th and 40th United States Congresses from March 4, 1865 to March 3, 1867. As a congressman, he served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Conkling had been re-elected to the 41st United States Congress in November 1866, but did not take his seat, instead entering the U.S. Senate.

Conkling was elected in January 1867 a U.S. Senator from New York, and re-elected in 1873 and 1879, served from March 4, 1867 to May 16, 1881. Through the eight years of President Grant's administration (March 4, 1869 to March 4, 1877), he stood out as the spokesman of the President and one of the principal leaders of the Republican Party in the Senate. In 1873, Grant urged him to accept an appointment as Chief Justice of the United States, but Conkling declined.[10] Conkling was active in framing and pushing through Congress the reconstruction legislation, and was instrumental in the passage of the second Civil Rights Act of 1875, and of the act for the resumption of specie payments, in the same year. He was Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Revision of the Laws of the United States (40th - 43rd Congresses), of the United States Senate Committee on Commerce (44th, 45th and 47th Congresses), of the U.S. Senate Committee on Engrossed Bills (46th and 47th Congresses).

Conkling was entirely out of sympathy with the reform element in the Republican Party. His first break with the Hayes administration occurred in April 1877 when the Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman appointed a commission to investigate the affairs of the New York Custom House. The investigation brought to light extensive irregularities in the service, showing in particular that the federal office holders in New York constituted a large army of political workers, and that their positions were secured by and dependent upon their faithful service in behalf of the men holding the principal government offices in the city.

President Hayes decided upon the removal of Chester A. Arthur, the Collector, General George H. Sharpe, the Surveyor, and A.B. Cornell, the Naval Officer of the Port, and in October 1877, sent nominations of their successors to the Senate. Senator Conkling defended the displaced officials, and, through his influence in the Senate, secured the rejection of the new nominations. He succeeded in blocking all the efforts of President Hayes and Secretary Sherman until January 1879, when, a new lot of nominations having been made, they were confirmed in spite of Conkling's continued opposition.

Early in 1880, Senator Conkling became the leader of the movement for the nomination of General Grant for a third term in the Presidency. He had a strong regard for Grant, and was hostile to the other two leading Republican candidates, Sherman, with whom he had come into conflict during Hayes' administration, and James G. Blaine, whose bitter political and personal enemy he had been for 24 years. The convention, after 33 generally consistent, inconclusive ballots, by a combination of the Blaine and Sherman interests, nominated James A. Garfield on the 36th ballot. Conkling and the other faithful Grant Stalwarts were allowed to name the candidate for vice presidency, Chester A. Arthur.

Immediately after Garfield's inauguration, Conkling presented to the President a list of men whom he desired to have appointed to the federal offices in New York. Garfield's appointment of Blaine as Secretary of State, and of William Windom as Secretary of the Treasury, instead of Levi P. Morton, whose appointment Conkling had urged, angered Conkling and made him unwilling to agree to any sort of compromise with Garfield on the New York appointments. Without consulting him, the President nominated for Collector of the Port of New York William H. Robertson, the leader of the opposing Half-Breed faction. Robertson's nomination was confirmed by the Senate, in spite of the opposition of Conkling, who claimed the right of Senators to control federal patronage in their home states.

In protest, Conkling resigned with his fellow Senator Thomas C. Platt, confident that he would be re-elected by the New York legislature (at the time, senators were chosen by their states' legislatures). However, he was defeated in the resulting special election after an almost two-month-long struggle between the opposing factions of the Republican Party.

Afterwards he resumed the practice of law in New York City. He declined a nomination to the United States Supreme Court in 1882.

Actions in the House and the Senate

- He was an enthusiastic supporter of the Lincoln administration and its conduct of the American Civil War.

- He defended a proposal ordering the construction of a transcontinental telegraph to the Pacific Ocean.

- He opposed the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in Dred Scott v. Sanford.

- He opposed the generalship of George B. McClellan.

- He helped draft the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution.

- He was a Radical Republican favoring equal rights for ex-slaves and reduced rights for ex-Confederates. He was active in framing and pushing through Congress the Reconstruction legislation, and was instrumental in the passage of the second Civil Rights Act in 1875.

- In the Republican National Convention at Cincinnati in 1876, Conkling first appeared as a presidential candidate, initially receiving 93 votes. His votes would later be thrown behind Rutherford B. Hayes in order to prevent the ascension of James G. Blaine.

- He was one of the framers of the bill creating the Electoral Commission to decide the disputed election of 1876.

- He championed the broad interpretation of the ex post facto clause in the Constitution (See Stogner v. California)

- After resigning from the Senate in 1881, he became a lawyer. As one of the original drafters of the Fourteenth Amendment, he claimed in a case which reached the Supreme Court, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, 118 U.S. 394 (1886),[11] that the phrase "nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws" meant the drafters wanted corporations to be included, because they used the word "person" and cited his personal diary from the period. Howard Jay Graham, a Stanford University historian considered the pre-eminent scholar on the Fourteenth Amendment, named this case the "conspiracy theory" and concluded that Conkling probably perjured himself for the benefit of his railroad friends.[12]

Relationship with Chester Arthur

Conkling, a machine Republican, led the Stalwart (pro-Grant) faction of the GOP, in opposition to the "Half-Breeds" led by James G. Blaine. Conkling served as a mentor to Chester A. Arthur, beginning in the late 1860s. Arthur received from Conkling a tax commission post (along with a salary of $10,000), and was later appointed Collector of the Port of New York. However, in 1878 Conkling lost a key battle against Rutherford B. Hayes’s civil service reform. Hayes bypassed any vote on Arthur’s removal from office by simply promoting Edwin Merritt from Surveyor of the Port of New York to Collector, thus superseding Arthur. Conkling and Arthur were so intimately associated that it was feared, after President James A. Garfield was assassinated, that the killing had been done at Conkling's behest in order to install Arthur as president. Arthur later offered Conkling an appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court, although it was thought the gesture was merely "complimentary," that Conkling was too partisan to make a good Justice, and that Arthur was paying back his patron with the honor of nomination, even though it was expected Conkling would refuse. However, Conkling had a great reputation as a trial lawyer, and he had once before (in 1873) been offered the chief justiceship by President Grant. At that time Conkling had rejected the offer. He accepted this offer from Arthur and was voted into the position by the U.S. Senate, but then declined to take office, becoming the last confirmed nominee to refuse to serve.[13][14]

In fact, Arthur's and Conkling's relationship was destroyed by the former's accession to the presidency. The Stalwarts faction that Conkling led was opposed to civil service reform, advocating instead the old patronage system of political appointments. Conkling was not consulted by Garfield (a member of the rival Republican faction, the Half-Breeds), about the appointment of William H. Robertson as Collector of the Port of New York, causing Conkling to protest by resigning from the U.S. Senate. Then, Conkling tried to force the Republican majority of the New York State Legislature to re-elect him, affirming his status as the New York Republican leader, but was blocked successfully by the Half-Breed faction, and Conkling's congressional career ended. When Arthur became president upon Garfield's death, Conkling attempted to sway his protégé into changing the appointment. Arthur, who would become an avid champion of civil service reform, refused. The two men never repaired the breach. Without Conkling's leadership, his Stalwart faction dissolved. However, upon Arthur's death in 1886, Conkling attended the funeral and showed deep sorrow according to onlookers.

Personal life

Conkling had a reputation as a womanizer and philanderer, and was accused of having an affair with the married Kate Chase Sprague, daughter of Salmon P. Chase and wife of William Sprague IV. According to a well-known story, buttressed by contemporaneous press reports, Mr. Sprague confronted the philandering couple at the Spragues' Rhode Island summer home and pursued Conkling with a shotgun.[15] One account from the New York Times (October 12, 1909) states:

The late Senator Roscoe Conkling was a frequent visitor at Canonchet [Sprague's estate], and was unpleasantly conspicuous in the proceedings which ended in the divorce of the Spragues. Mr. Conkling was once forbidden by Mr. Sprague to come to Canonchet. Despite this, however, the Executive [Sprague] later met the Senator [Conkling] on the estate coming from the rear of the house—some reports had it that the Senator jumped from a window—and after him came the Governor with his old civil war musket in his hands.[16]

Conkling's stature as a powerful politician—and the interests of others in currying favor with him—led to many babies being named for him. These include Roscoe Conkling Patterson, Roscoe Conkling Oyer, Roscoe Conkling Bruce, and Roscoe Conkling McCulloch.[17] Roscoe Conkling ("Fatty") Arbuckle's father, however, despised Conkling; he named the boy so because he suspected the boy was not his, and because of Conkling's known philandering.[18]

Death

On March 12, 1888, during the Great Blizzard of 1888, Conkling attempted to walk three miles from his law office on Wall Street to his home on 25th Street near Madison Square. Conkling made it as far as Union Square before collapsing. He contracted pneumonia and died several weeks later, on April 18, 1888.[19] He is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica. A statue of him stands in Madison Square Park in New York City. Roscoe, New York, is named for him.[20]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Paxson, p. 346.

- ^ a b Paxson, p. 347.

- ^ "Roscoe Conkling". NNDB. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ Alfred Ronald Conkling, The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling, Orator, Statesman, Advocate (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1889), p. 11-13.

- ^ A.R. Conkling, "Life and Letters," pp. 11-13.

- ^ A.R. Conkling, "Life and Letters," pp. 14.

- ^ A.R. Conkling, "Life and Letters," pp. 16.

- ^ A.R. Conkling, "Life and Letters," pp. 16-17.

- ^ Henry Scott Wilson, "Distinguished American Lawyers: With Their Struggles and Triumphs in the Forum," (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1891), p. 190.

- ^ Roscoe Conkling Legal Dictionary Online

- ^ San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific R. Co., 116 U. S. 138 (1885)

- ^ Graham, Howard J., The “Conspiracy Theory” of the Fourteenth Amendment, 47 Yale L. J. 371 (1938).

- ^ Conkling, Alfred Ronald (1889). Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling:. New York, NY: Charles L. Webster & Company. p. 677.

- ^ Abraham, Henry J.; Goldberg, Edward M. (February 1, 1960). "The Appointment of Supreme Court Justices". American Bar Association Journal. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association: 220.

- ^ Peg A. Lamphier, Kate Chase and William Sprague: Politics and Gender in a Civil War Marriage, University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- ^ CANONCHET, SPRAGUE HOME IS BURNED: War Governor in Danger as Place Is Destroyed with Loss Exceeding $1,000,000. PRICELESS RELICS LOST House, Remnant of William Sprague's Vast Fortune, Was Identified with Stirring Events in Nation's Annals. New York Times, Oct. 12, 1909, p. 18

- ^ Melissa Block, Roscoe Conkling, "All Things Considered", National Public Radio, April 18, 2001.

- ^ Ellis, Chris & Julie (April 10, 2005). The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder: Murder played out in the spotlight of maximum publicity. Constable & Robertson. ISBN 978-0786715688. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ [1] Bad Idea: The Most Powerful Man in America Walks Home Through the Blizzard of 1888

- ^ Rockland Sullivan County Historical Society

Bibliography

- United States Congress. "Roscoe Conkling (id: C000681)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Burlingame, Sara Lee. "The Making of a Spoilsman: The Life and Career of Roscoe Conkling from 1829 to 1873." PhD dissertation Johns Hopkins U. 1974. 419 pp.

- Eidson, William G. "Who Were the Stalwarts?" Mid-America 1970 52(4): 235-261. ISSN 0026-2927

- Graham, Howard Jay. “The ‘Conspiracy Theory’ of the Fourteenth Amendment”. The Yale Law Journal. Vol. 47, No. 3. (January, 1938), pp. 371–403.

- David M Jordan. Roscoe Conkling of New York: voice in the Senate, (1971) (ISBN 0801406250) the standard scholarly biography

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969)

- Paxson, Frederic Logan (1930). Dictionary of American Biography Conkling, Roscoe. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Peskin, Allan. Conkling, Roscoe American National Biography Online, (February 2000), (29 January 2007).

- Peskin, Allan. "Who Were the Stalwarts? Who Were Their Rivals? Republican Factions in the Gilded Age." Political Science Quarterly 1984-1985 99(4): 703-716. ISSN 0032-3195 Fulltext: online in Jstor

- Reeves, Thomas C. “Chester A. Arthur and the Campaign of 1880”. Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 84, No. 4. (December, 1969), pp. 628–637.

- Reeves, Thomas C. "Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur," (1975) (ISBN 0-394-46095-2).

- Shores, Venila Lovina. The Hayes-Conkling Controversy, 1877-1879 (Smith College Studies in History, Vol. IV, No. 4, July, 1919), Northampton, MA, 1919. In The Spoils System in New York. Edited by James MacGregor Burns and William E. Leuchtenburg. New York: Arno Press, Inc. 1974.

- Swindler, William F. "Roscoe Conkling and the Fourteenth Amendment." Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1983: 46-52. ISSN 0362-5249

Encyclopedias

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . . 1914.

Primary sources

- A. R. Conkling (editor), The Life and Letters of Roscoe Conkling: Orator, Statesman, Advocate (1889)

- The Nation, March 2, 1882

- Eaton, Dorman B., The Spoils System and Civil Service Reform in the Custom-House and Post-Office at New York (Publications of the Civil Service Reform Association, No. 3), New York, 1881. In The Spoils System in New York. Edited by James MacGregor Burns and William E. Leuchtenburg. New York: Arno Press, Inc. 1974.

External links

- Mr. Lincoln and New York: Roscoe Conkling

- United States Congress. "Roscoe Conkling (id: C000681)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.. Includes Guide to Research Collections where his papers are located.

- Roscoe Conkling at Find a Grave

- 1829 births

- 1888 deaths

- American political bosses from New York

- County district attorneys in New York

- Gardiner family

- Mayors of Utica, New York

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York

- New York Republicans

- People from Albany, New York

- People from Manhattan

- People of New York in the American Civil War

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Republican Party United States Senators

- United States Senators from New York