Sadness

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (March 2013) |

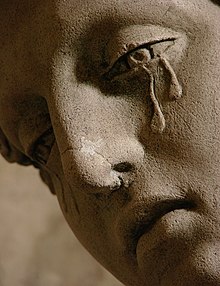

Sadness is emotional pain associated with, or characterized by feelings of disadvantage, loss, despair, helplessness and sorrow. An individual experiencing sadness may become quiet or lethargic, and withdraw themselves from others. Crying is often an indication of sadness.[1] Sadness is one of the "six basic emotions" described by Paul Ekman, along with happiness, anger, surprise, fear and disgust.[2] Sadness can be viewed as a temporary lowering of mood, whereas depression is more chronic.[citation needed]

In childhood

Sadness is a common experience in childhood. Acknowledging such emotions can make it easier for families to address more serious emotional problems,[3] although some families may have a (conscious or unconscious) rule that sadness is "not allowed".[4] Robin Skynner has suggested that this may cause problems when "screened-off emotion isn't available to us when we need it... the loss of sadness makes us a bit manic".[5]

Sadness is part of the normal process of the child separating from an early symbiosis with the mother and becoming more independent. Every time a child separates just a tiny bit more, he or she will have to cope with a small loss. Skynner suggests that if the mother cannot bear this and "dashes right in to relieve the child's distress every single time he shows any... the child is not getting a chance to learn how to cope with sadness'".[6] Pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton argues that "trying to jostle or joke out of a sad mood is devaluing to her"[7] and Selma Fraiberg suggests that it is important respecting a child's right to experience a loss fully and deeply.[8]

Margaret Mahler believes that sadness requires "a great deal of strength" to bear, and that a child in self-protection may develop "hyperactivity or restlessness...as an early defensive activity against awareness of the painful affect of sadness".[9] This is why D. W. Winnicott suggests that "when your infant shows that he can cry from sadness you can infer that he has travelled a long way in the development of his feelings....some people think that sad crying is one of the main roots of the more valuable kind of music".[10]

Neuroanatomy

According to the American Journal of Psychiatry and Psychopaths, sadness was found to be associated with "increases in bilateral activity within the vicinity of the middle and posterior temporal cortex, lateral cerebellum, cerebellar vermis, midbrain, putamen, and caudate."[11] Jose V. Pardo has his M.D and Ph.D and leads a research program in cognitive neuroscience. Using positron emission tomography (PET) Pardo and his colleagues were able to provoke sadness among seven normal men and women by asking them to think about sad things. They observed increased brain activity in the bilateral inferior and orbitofrontal cortex. [12] Sadness is associated with significant increases in regional brain activity, especially in the prefrontal cortex, in an area called the (Brodmann’s area 9) as well as in the thalamus. Also, there is a significant increase in activity, in the bilateral anterior temporal structures, however this was attributed to film-induced emotions. [13]

Coping mechanisms

Daniel Goleman says that "the single mood people generally put most effort into shaking is sadness...Unfortunately, some of the strategies most often resorted to can backfire, leaving people feeling worse than before. One such strategy is simply staying alone."[14] Ruminating, and "drowning one's sorrows", may also be counterproductive. Being attentive and patient with sadness is one way for people to learn through solitude. [15] Goleman suggests two more positive alternatives which have been recommended by cognitive therapy. "One is to learn to challenge the thoughts at the center of rumination and think of more positive alternatives. The other is to purposely schedule pleasant, distracting events".[16]

Object relations theory by contrast stresses the utility of staying with sadness: 'it's got to be conveyed to the person that it's all right for him to have the sad feelings' – easiest done perhaps 'where emotional support is offered to help them begin to feel the sadness'.[17] Such an approach is fuelled by the underlying belief that 'the capacity to bear loss wholeheartedly, without pushing the experience away, emerges...as essential to being truly alive and engaged with the world'.[18]

When some individuals feel sad, they may exclude themselves, in doing so they take time to recover from this feeling. People deal with sadness in different ways, and it is an important emotion because it helps to motivate people to deal with their situation. Some coping mechanism could include: creating a list, getting support from others, spending time with a pet or engaging in something to express sadness such as dance. [19]

Sadness increases impatience and creates a myopic focus on obtaining money immediately instead of later. This focus, in turn, increases intertemporal discount rates and thereby produces substantial financial costs. A sadder person is not necessarily the wiser person when it comes to financial choices. Instead, compared with neutral emotion, sadness—but not disgust—made people more myopic, and therefore willing to forgo greater future gains in return for instant gratification.[20]

Pupil empathy

Facial expressions of sadness with small pupils are judged significantly more intensely sad with decreasing pupil size. A person's own pupil size also mirrors this with them being smaller when viewing sad faces with small pupils. No parallel effect exists when people look at neutral, happy or angry expressions.[21] The greater degree to which a person's pupils mirror another predicts a person's greater score on empathy.[22] However, in disorders such as autism and psychopathy facial expressions that represent sadness may be subtle, which may show a need for a more non-linguistic situation to affect their level of empathy.[22]

Cultural explorations

During the Renaissance, "Edmund Spenser's high estimation of sadness renders it as a badge of sort for the spiritually elect...this endorsement of sadness"[23] in The Fairie Queene.

In The Lord of the Rings, Treebeard is described as having "a sad look in his eyes, sad but not unhappy".[24] This may be linked to the way "an early meaning of 'sad' is 'settled, determined'", exemplifying "Tolkien's theses that determination should survive the worst that can happen".[25]

Julia Kristeva considered that 'a diversification of moods, variety in sadness, refinement in sorrow or mourning are the imprint of a humanity that is surely not triumphant but subtle, ready to fight and creative'.[26]

See also

References

- ^ Jellesma F.C., & Vingerhoets A.J.J.M. (2012). Sex Roles (Vol. 67, Iss. 7, pp. 412-421). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer

- ^ Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (London 1996) p. 271

- ^ T. Berry Brazleton, To Listen to a Child (1992) p. 46 and p. 48

- ^ Masman, Karen (2010). The Uses of Sadness: Why Feeling Sad Is No Reason Not to Be Happy. Allen & Unwin. p. 8. ISBN 9781741757576.

- ^ Skynner/Cleese, p. 33 and p. 36

- ^ Skynner/Cleese, p. 158–9

- ^ Brazleton, p. 52

- ^ Selma H. Fraiberg, The Magic Years (New York 1987) p. 274

- ^ M. Mahler et al, The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant (London 1975) p. 92

- ^ D. W. Winnicott, The Child, the Family, and the Outside World (Penguin 1973) p. 64

- ^ Ahern, G.L., Davidson, R.J., Lane, R.D., Reiman, E.M., Schwartz, G.E. (1997). Neuroanatomical Correlates of Happiness, Sadness, and Disgust. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 926-933.

- ^ Pardo JV, Pardo PJ, Raichle ME: Neural correlates of self-in- duced dysphoria. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:713–719

- ^ George MS, Ketter TA, Parekh PI, Horowitz B, Herscovitch P, Post RM: Brain activity during transient sadness and happiness in healthy women. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:341–351

- ^ Goleman, p. 69–70

- ^ Aliki Barnstone New England Review (1990-) , Vol. 21, No. 2 (Spring, 2000), p. 19

- ^ Goleman, p. 72

- ^ Skynner/Cleese, p. 164

- ^ Michael Parsons, The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (London 2000) p. 4

- ^ "Feeling Sad", Kids Help Phone, November 2010

- ^ Lerner, Jennifer S. (2013). "The Financial Costs of Sadness". Psychological Science: 24(1) 72–79. doi:10.1177/0956797612450302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harrison NA, Singer T, Rotshtein P, Dolan RJ, Critchley HD (2006). "Pupillary contagion: central mechanisms engaged in sadness processing". Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 1 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl006. PMC 1716019. PMID 17186063.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Harrison NA, Wilson CE, Critchley HD (2007). "Processing of observed pupil size modulates perception of sadness and predicts empathy". Emotion. 7 (4): 724–9. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.724. PMID 18039039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Douglas Trevor, The Poetics of Melancholy in early modern England (Cambridge 2004) p. 48

- ^ J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (London 1991) p. 475

- ^ T. A Shippey, The Road to Middle-Earth (London 1992) p. 143

- ^ Quoted in Adam Phillips, On Flirtation (London 1994) p. 87

Further reading

- Karp DA (1997). Speaking of Sadness. ISBN 0195113861.

- Keltner D, Ellsworth PC, Edwards K (1993). "Beyond simple pessimism: effects of sadness and anger on social perception". J Pers Soc Psychol. 64 (5): 740–52. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.740. PMID 8505705.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tiedens LZ (2001). "Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: the effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral". J Pers Soc Psychol. 80 (1): 86–94. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.86. PMID 11195894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ambady & Gray, 2002

- Forgas JP (1998). "On feeling good and getting your way: mood effects on negotiator cognition and bargaining strategies". J Pers Soc Psychol. 74 (3): 565–77. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.565. PMID 11407408.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Forgas JP (1998). "On being happy and mistaken: mood effects on the fundamental attribution error". J Pers Soc Psychol. 75 (2): 318–31. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.318. PMID 9731311.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Forgas JP (1994). "The role of emotion in social judgments: an introductory review and an Affect Infusion Model (AIM)". Eur J Soc Psychol. 24 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420240102.

- Forgas JP, Bower GH (1987). "Mood effects on person-perception judgments". J Pers Soc Psychol. 53 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.53. PMID 3612493.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Isen AM, Daubman KA, Nowicki GP (1987). "Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving". J Pers Soc Psychol. 52 (6): 1122–31. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1122. PMID 3598858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Keltner D, Kring AM (1998). "Emotion, social function, and psychopathology" (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 2 (3): 320–342.