St George's Hall, Liverpool

| St George's Hall | |

|---|---|

St George's Hall | |

| Location | Lime Street, Liverpool, England |

| OS grid reference | SJ 349 907 |

| Built | 1841–1854 |

| Architect | Harvey Lonsdale Elmes Sir Charles Cockerell |

| Architectural style(s) | Neoclassical |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

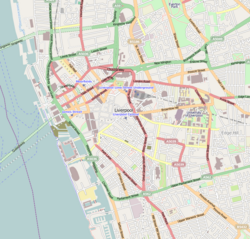

St George's Hall is on Lime Street in the centre of the English city of Liverpool, opposite Lime Street railway station. It is a building in Neoclassical style which contains concert halls and law courts, and has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building.[1] On the east side of the hall, between it and the railway station is St George's Plateau and on the west side are St John's Gardens. The hall is included in the William Brown Street conservation area.[2] In 1969 the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner expressed his opinion that it is one of the finest neo-Grecian buildings in the world[3] although the building is notable for its use of Roman sources as well as Greek ones. In 2004 the hall and its surrounding area were recognised as part of Liverpool's World Heritage Site.[4]

History

The site of the hall was formerly occupied by the first Liverpool Infirmary from 1749 to 1824. Triennial music festivals were held in the city but there was no suitable hall to accommodate them.[5] Following a public meeting in 1836 a company was formed to raise subscriptions for a hall in Liverpool to be used for the festivals, and for meetings, dinners and concerts.[6] Shares were made available at £25 each and by January 1837 £23,350 (£Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2,024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2,023) in index "UK". as of 2024),[7] had been raised. In 1838 the foundation stone was laid to commemorate the coronation of Queen Victoria.[5] A competition in 1839 to design the hall was won by Harvey Lonsdale Elmes, a London architect aged 25 years. There was a need for assize courts in the city and a competition to design these was also won by Elmes. The original plan was to have separate buildings but in 1840 Elmes suggested that both functions could be combined in one building on a scale which would surpass most of the other public buildings in the country at the time. Construction started in 1841, the building opened in 1854 (with the small concert room opening two years later). Elmes died in 1847 and the work was continued by John Weightman, Corporation Surveyor, and Robert Rawlinson, structural engineer, until in 1851 Sir Charles Cockerell was appointed architect. Cockerell was largely responsible for the decoration of the interiors.[8] During the 2000s a major restoration of the hall took place costing £23m and it was officially reopened on 23 April 2007 by HRH Prince of Wales.[9]

Structure

Plan

The Concert Hall is the largest area, rectangular in shape, and occupies the centre of the building with an organ on its north wall. To the north of the Concert Hall is the Civil Court and beyond this is the elliptical Small Concert Room. To the south of the Concert Hall are the Crown Court and the Grand Jury Room. Smaller court rooms are on the periphery of the larger courts.[10] The floor below consists of a cavernous basement with cells for prisoners along the west wall.[11]

Exterior

The main entrance is in the centre of the east façade and is approached by a wide flight of steps.[12] On the steps is a statue of Benjamin Disraeli by Charles Bell Birch.[11] At the south-east corner is a bronze statue of Major-General William Earle by the same sculptor. This front has a central portico of 16 Corinthian columns flanked on each side by series of square, unfluted pillars. Between these pillars are reliefs which were added between 1882 and 1901 by Thomas Stirling Lee, C. J. Allen and Conrad Dressler. The west front has a projecting central part with square pillars supporting a massive entablature. The south front has a portico of eight columns, two columns deep on steps above a rusticated podium. The north front has a semicircular apse with columns and three doorways which are flanked by statues of nereids and tritons bearing lamps which were designed by Nicholl.[12]

Interior

The main entrance crosses a corridor and leads into the Concert Hall. This measures 169 feet (52 m) by 77 feet (23 m) and is 82 feet (25 m) high. The roof is a tunnel vault carried on columns of polished red granite. The walls have niches for statues and the panelled plasterwork of the vault has allegorical figures of Virtues, Science and Arts. The highly decorated floor consists of Minton tiles and it is usually covered by a removable floor to protect it.[13] It contains over 30,000 tiles.[14] The floor will be on display for 2 weeks in January 2012.[15] The doors are bronze and have openwork panels which incorporate the letters SPQL (the Senate and the People of Liverpool) making an association with the SPQR badge of ancient Rome. The organ is at the north end and at the south end is a round arch supporting an entablature between whose columns is a gate leading directly into the Crown Court. The niches contain the statues of William Roscoe by Chantrey, Sir William Brown by Patrick MacDowell, Robert Peel by Matthew Noble, George Stephenson by John Gibson, Hugh Boyd M‘Neile by George Gamon Adams, Edward Whitley by A. Bruce Joy, S. R. Graves by G. G. Fontana, Rev Jonathan Brookes by B. E. Spence, William Ewart Gladstone by John Adams-Acton, the 14th Earl of Derby by William Theed the Younger, the 16th Earl of Derby by F. W. Pomeroy, and Joseph Mayer by Fontana.[13] In 2012, a statue of Kitty Wilkinson by Simon Smith was unveiled, the first in 101 years, and the first of a woman.[16] The stained glass in the semicircular windows at each end of the hall was added in 1883–84 by Forrest and Son of Liverpool. Sharples and Pollard regard this as "one of the greatest Victorian interiors".[13]

The Crown Court has a tunnel vault on red granite columns and the Civil Court a coved ceiling on grey granite columns. The south entrance is approached through the portico, is low and has Ionic columns. Below this is a larger vaulted space which was adapted to form a new entrance in 2003–05. The north entrance hall has Doric columns on its landing and a Doric ambulatory around the apse. A copy of part of the Parthenon frieze runs round its walls. In the entrance is a statue of Henry Booth by Theed the Younger. The Small Concert Room is almost circular and is lavishly decorated.[17] In the past it was known as the Golden Concert Room and it was regularly host to Charles Dickens who held many of his readings there.[18] A balcony supported by caryatids runs round the room. At the back of the platform are attached columns, decorated with arabesques, supporting a frieze with griffins and between the columns are mirrors.[17] The concert room was refurbished between 2000 and 2007. This included making alterations to comply with the Disability Discrimination Act, restoring the historical painting scheme and restoring the chandelier, which consists of 2,824 crystal pieces.[19] It has seating for an audience of 480.[18]

In the basement is part of a unique heating and ventilation system devised by Dr Boswell Reid.[11] This was the first attempt at air conditioning in a public building in the United Kingdom, its aim being to warm and ventilate the building without draughts. Air was warmed by five hot water pipes which were heated by two coke-fired boilers and two steam boilers. The air was circulated by four 10 feet (3 m) wide fans. It was controlled a large number of workers opening and closing a series of canvas flaps.[20]

Organ and organists

The organ was built by Henry Willis and completed in 1855 with 100 speaking stops across four manual divisions (of non-standard compass, 63 notes GG to a) and pedals (30 notes). It comprised a total of 119 ranks of pipes, plus 10 couplers, 10 composition pedals, and 36 pistons to set combinations of stops. It was initially tuned to meantone temperament to the specification of S. S. Wesley but in 1867 W. T. Best, city organist, retuned it to equal temperament. The organ was rebuilt in 1896 when the key action was changed from the Willis-Barker lever assisted tracker (i.e. pneumatic assisted mechanical) action to pneumatic action. Also the manual compass was changed to the now standard CC to c, 61 notes, making the bottom 5 pipes on every manual stop redundant.[21] In 1931 it was reconstructed by Henry Willis III when the number of stops was increased to 120 and electro-pneumatic action introduced for the combination systems and some of the key action. Its power source was still the Rockingham electric blowing plant which had replaced the two steam engines (one of 1855 and a second which had been added in about 1877 to run the increased pressure required since 1867 for some reed stops. In the interim this higher pressure had been hand blown!) The 1924 electric blowers remained in use until 2000 when the present new low and high pressure blowers were fitted by David Wells.[22]

In 1979 it was given a general clean and overhaul by Henry Willis IV. The total number of registers, including 24 couplers, is 144.[21] With 7,737 pipes, it was the largest organ in the country until a larger one was built at the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, after which an organ even larger than the one at the Royal Albert Hall was constructed at Liverpool Anglican Cathedral, using over 10,000 pipes.[14] As part of the 2000–2007 restoration of the hall repairs were made to the organ, including replacement of the bellows leather.[23] The organ is maintained by David Wells, Organ Builders.[24]

It is currently the 3rd largest Organ in the UK

The first organist was W. T. Best (1826–97) who was appointed in 1855 and served until 1894. He was succeeded in 1896 by Dr Albert Lister Peace (1844–1912) who continued in the post until the year of his death. In 1913 Herbert Frederick Ellingford (1876–1966) was appointed organist.[25] On 21 December 1940 the hall and its organ were damaged in an air-raid. It was not possible to obtain sufficient money to rebuild the organ until the 1950s. In 1954 Henry Willis & Sons were asked to undertake this project and Dr Caleb E. Jarvis (1903–80) was its consultant.[26] Dr Jarvis was appointed organist in 1957 and on his death in 1980 he was succeeded by Noel Rawsthorne (born 1929), who had just retired as organist to the Anglican Cathedral.[27] Noel Rawsthorne served as organist to the hall for four years.[28] Following his retirement in 1984, Professor Ian Tracey, who is also Organist Titulaire of the Anglican Cathedral, was appointed to the post.[29]

St George's Plateau

This is the flat space between the hall and the railway station and contains statues of four lions by Nicholl and cast iron lamp standards with dolphin bases. Also on the plateau are monuments, including equestrian bronzes of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria by Thomas Thornycroft, and a monument to Major-General William Earle by Birch. Between the equestrian statues is Liverpool Cenotaph which was unveiled in 1930, designed by L. B. Budden and sculpted by H. Tyson Smith. It consists of a simple horizontal block with a bronze relief measuring over 31 feet (9 m) on each side. Sharples and Pollard regard it as one of the most remarkable war memorials in the country.[11]

The Plateau has been associated with public rallies and gatherings, including the deaths of Beatles, John Lennon and George Harrison, and the homecomings of Liverpool and Everton football teams after Cup Final Victories.[30] During the 1911 Liverpool General Transport Strike, many meetings were held there, including the rally which sparked the 'Bloody Sunday' attacks, when police baton charged thousands of people who had gathered to hear syndicalist Tom Mann speak.[31]

Restoration

Following the restoration leading to the reopening of the hall in April 2007 it was granted a Civic Trust Award.[32] It included the creation of a Heritage Centre which gives an introduction to the hall and its history. Guided tours, a programme of exhibitions and talks are arranged.[9] Over the 2007 and 2008 Christmas periods an artificial skating rink was installed in the Concert Hall.[33] In January 2008 Liverpool started its tenure as European Capital of Culture with The People's Opening at St George's Hall with a performance which included Beatles' drummer Ringo Starr playing on its roof.[34]

See also

Gallery

- external features

-

colourized photo taken in the 1890s.

-

Main Entrance to the Hall

-

Equestrian statue of Prince Albert outside the hall.

-

eastern portico

-

relief, eastern elevation

-

lampholder, eastern elevation

-

relief, eastern elevation

-

lampholder, eastern elevation

-

external door, eastern portico

-

View from the main steps of Lime Street Station

- internal features

-

the widest barrel-vaulted ceiling in the UK

-

Stained glass window of St. George slaying the dragon

-

internal door

-

detail of goddess on door

-

statue of Gladstone

-

Crown Court

-

statue of 14th Earl of Derby

-

Minton floor

-

statue supporting the organ loft

-

statue of William Roscoe

References

Citations

- ^ "St George's Hall, Liverpool", The National Heritage List for England, English Heritage, 2011, retrieved 9 May 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The City of Liverpool Conservation Areas (pdf), City of Liverpool, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Quoted in Sharples & Pollard 2006, p. 247.

- ^ Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City, UNESCO, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b History of the Hall, BBC, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sharples & Pollard 2006, p. 291.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Sharples & Pollard 2006, pp. 291, 293.

- ^ a b St Georges Hall, The Mersey Partnership, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sharples & Pollard 2006, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d Sharples & Pollard 2006, p. 297.

- ^ a b Sharples & Pollard 2006, p. 294.

- ^ a b c Sharples & Pollard 2006, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Facts & figures, BBC, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tiles of the unexpected to go on show at Liverpool's St George’s Hall in the New Year

- ^ Kitty Wilkinson Statue Unveiled, Liverpool Express, Liverpool City Council, retrieved 24 September 2013

- ^ a b Sharples & Pollard 2006, pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b St George's Hall, Concert Room, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ St George's Hall, Liverpool, World Monuments Fund Britain, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Air conditioning, BBC, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Cromwell, Peter, The Organ in St George's Hall, Liverpool, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Great Hall, BBC, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ St George's Hall organ to be restored, The Organ, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ David Wells, Organ Builders, David Wells, Organ Builders, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Carrington 1981, pp. 35–39.

- ^ Carrington 1981, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Carrington 1981, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Biography, Ian Tracey, retrieved 27 October 2009

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The Magic of St George's Hall, Northwest Vision and Media, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Braddock, (Bessie) Elisabeth, Liverpool History Online, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ St George's Hall scoops heritage 'Oscars' double, Liverpool 08, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Williams, Lisa (22 December 2007), "Ice rink opens inside St George's Hall for Christmas", Liverpool Daily Post, Trinity Mirror North West & North Wales, retrieved 27 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Perrone, Pierre (15 January 2008), "Liverpool 08: The People's Opening, St George's Hall", The Independent, retrieved 26 March 2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

Sources

- Carrington, Douglas R. (1981), St George's Hall: The Hall, Organ and Organists, Liverpool: Liverpool City Council, OCLC 30775781

- Sharples, Joseph; Pollard, Richard. Liverpool. In Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006), Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10910-5

External links

![]() Media related to St. George's Hall, Liverpool at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St. George's Hall, Liverpool at Wikimedia Commons

- Concert halls in England

- Grade I listed buildings in Liverpool

- Grade I listed concert halls

- Grade I listed law buildings

- Visitor attractions in Liverpool

- Museums in Liverpool

- Prison museums in the United Kingdom

- History museums in Merseyside

- Neoclassical architecture in Liverpool

- Greek Revival architecture in the United Kingdom

- Government buildings completed in 1854