The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

| |

| Author | Charles Darwin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Evolutionary theory human behaviour |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | 1872 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is a book by Charles Darwin, published in 1872, concerning genetically determined aspects of behavior. It was published thirteen years after On the Origin of Species and, alongside his 1871 book The Descent of Man (of which it was originally intended to form a part), it is Darwin's main consideration of human origins. In this book, Darwin seeks to trace the origins of such human characteristics as the lifting of the eyebrows in moments of surprise and the mental confusion which typically accompanies blushing. Darwin links mental states to the neurological organization of movement; and he sought out the opinions of some leading British psychiatrists, notably James Crichton-Browne, in the preparation of the book which forms his main contribution to psychology.[1] Amongst the innovations with this book are Darwin's circulation of a questionnaire in his preparatory research; simple psychology experiments on emotional recognition with his friends and family; and (borrowing from Duchenne de Boulogne, a physician at the Salpêtrière) the use of photographs in his presentation of scientific information. The Expression of the Emotions is an important landmark in the history of book illustration.

The book's development: biographical aspects

In the weeks before Queen Victoria's coronation in 1838, Charles Darwin sought medical advice on his mysterious physical symptoms, and then travelled to Scotland for a period of rest and a "geologizing expedition" – but actually spent some of his time re-exploring the old haunts of his undergraduate days. On the day of the coronation, 28 June 1838, Darwin was in Edinburgh. A few days later, he opened a private notebook with philosophical and psychological speculation – the M Notebook – and, over the next three months, filled it with his thoughts about possible interactions of hereditary factors with the mental and behavioural aspects of human and animal life.[2]

The critical importance of the M notebook has usually been viewed in its relationship to Darwin's conception of natural selection as the central mechanism of evolutionary development, which he probably grasped some time around September 1838.[3][4][5] These notes have a tentative and fragmented quality, especially in Darwin's descriptions of conversation with his father (a successful doctor with a special interest in psychiatric problems) about recurring patterns of behaviour in successive generations of his patients' families.[6] Darwin was anxious about the materialistic drift in his thinking – and of the disrepute which this could attract in early Victorian England – at the time, he was mentally preparing for marriage with his cousin Emma Wedgwood who held firm Christian beliefs. On 21 September 1838, after his return to England, Darwin recorded a confused and disturbing dream in which he was involved in a public execution where the corpse came to life and claimed to have faced death like a hero.[7] In summary: Darwin put together the central features of his evolutionary theory at the same time that he was considering a scientific understanding of human behaviour and family life – and he was in some emotional turmoil. A discussion of the significance of Darwin's early notebooks can be found in Paul H. Barrett's Metaphysics, Materialism and the Evolution of Mind – Early Writings of Charles Darwin (1980).[2]

Mental qualities are determined by the size, form and constitution of the brain: and these are transmitted by hereditary descent.

— George Combe, The Constitution of Man Considered in Relation to External Objects (1828)

One is tempted to believe phrenologists are right about habitual exercise of the mind altering form of head, and thus these qualities become hereditary....When a man says I will improve my powers of imagination, and does so, – is not this free will ?...

— Charles Darwin, The M Notebook (1838)

To avoid stating how far I believe in Materialism, say only that emotions, instincts, degrees of talent, which are hereditary are so because brain of child resembles parent stock – (and phrenologists state that brain alters)....

— Charles Darwin, The M Notebook (1838)

Little of this surfaced in On the Origin of Species in 1859, although Chapter 7 contains a mildly expressed argument on instinctive behaviour.[8] In the public management of his evolutionary theory, Darwin understood that its relevance to human emotional life could draw a hostile response. Nevertheless, while preparing the text of The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication in 1866, Darwin took the decision to reinforce his public statement of evolutionary biology with a book on human ancestry, sexual selection and emotional life. After his initial correspondence with the psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne[9] Darwin set aside his material concerning emotional expression in order to complete The Descent of Man, which covered human ancestry and sexual selection. Darwin concluded work on The Descent of Man on 15 January 1871. Two days later, he started on The Expression of the Emotions and, on 22 August 1872, he finished work on the proofs. In this way, Darwin brought his evolutionary theory into close approximation with behavioural science, although many Darwin scholars have remarked on a kind of spectral Lamarckism haunting the text of the Emotions.[10]

Darwin notes the universal nature of expressions in the book, writing: "the young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements."

This connection of mental states to the neurological organization of movement (as the words motive, motivation and emotion suggest) is central to Darwin's understanding of emotion. Darwin himself displayed many biographical links between his psychological life and locomotion, taking long, solitary walks around Shrewsbury after his mother's death in 1817, in his seashore rambles near Edinburgh with the Lamarckian evolutionist Robert Edmond Grant in 1826/1827,[11][12][13] and in the laying out of the sandwalk, his "thinking path", at Down House in Kent in 1846.[14] These aspects of Darwin's personal relationships are discussed in John Bowlby's (1990) psychoanalytic biography of Darwin.[15]

Darwin emphasises a shared human and animal ancestry in sharp contrast to the arguments deployed in Charles Bell's Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression (1824)[16][17] which claimed that there were divinely created human muscles to express uniquely human feelings. Bell's famous aphorism on the whole subject was: "Expression is to the passions as language is to thought."

In The Expression, Darwin reformulates the issues at play, writing: "The force of language is much aided by the expressive movements of the face and body"

- hinting at a neurological intimacy of language with psychomotor function (body language),[18] although he does not particularly emphasise the communicative value of physical expression. Darwin had listened to a discussion about emotional expression at the Plinian Society in December 1826 when he was a medical student at Edinburgh University. This had been prompted by the 1824 publication of Bell's Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression; and in the debate, the phrenologist William A.F. Browne (in a typically spirited account of Robert Grant's Lamarckist philosophy) dismissed Bell's theological explanations, pointing instead to the striking similarities of human and animal anatomy. Darwin's response to Bell's neurological theories is discussed by Lucy Hartley (2001).[19]

In the composition of the book, Darwin drew on worldwide responses to his questionnaire (circulated in the early months of 1867) concerning emotional expression in different ethnic groups; on conversations with livestock breeders and pigeon fanciers; on observations on his infant son William Erasmus Darwin (A Biographical Sketch of an Infant); on simple psychology experiments with members of his family concerning the recognition of emotional expression; on the neurological insights of Duchenne de Boulogne, a physician at the Salpêtrière asylum in Paris; on hundreds of photographs of actors, babies and children; and on descriptions of psychiatric patients in the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum at Wakefield in West Yorkshire. Darwin corresponded intensively with James Crichton-Browne, the son of the phrenologist William A. F. Browne and the medical director of the Wakefield asylum.[20] At the time, Crichton-Browne was preparing his extremely influential West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports, and Darwin remarked to him that The Expression "should be called by Darwin and Browne". Darwin also drew on his personal experience of the symptoms of bereavement and studied the text of Henry Maudsley's 1870 Gulstonian lectures on Body and Mind.[21] He considered other approaches to the study of emotions, including their depiction in the arts – discussed by the actor Henry Siddons in his Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807) and by the anatomist Robert Knox in his Manual of Artistic Anatomy (1852) – but abandoned them as unreliable, although the text of The Expression is littered with descriptive quotations from Shakespeare.

Structure

Darwin opens the book with three chapters on "the general principles of expression", introducing the rather awkward phrase "associated serviceable habits". This is followed by a section (three more chapters) on modes of emotional expression peculiar to particular species, including man. He then moves on to the main argument with his characteristic approach of astonishingly widespread and detailed observations. Chapter 7 discusses "low spirits", including anxiety, grief, dejection and despair; and the contrasting Chapter 8 "high spirits" with joy, love, tender feelings and devotion. Subsequent chapters include considerations of "reflection and meditation" (associated with "ill-temper", sulkiness and determination), Chapter 10 on hatred and anger, Chapter 11 on "disdain, contempt, disgust, guilt, pride, helplessness, patience and affirmation" and Chapter 12 on "surprise, astonishment, fear and horror". In Chapter 13, Darwin discusses complex emotional states including self-attention, shame, shyness, modesty and blushing. Throughout these chapters, Darwin's concern was to show how human expressions link human movements with emotional states, and are genetically determined and derive from purposeful animal actions.

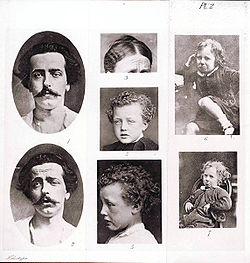

Illustrations

This was one of the first books to be illustrated with photographs – with seven heliotype plates[22] – and the publisher John Murray warned that this "would poke a terrible hole in the profits".[23]

The published book assembled illustrations rather like a Victorian family album, with engravings of the Darwin family's domestic pets by the zoological illustrator T. W. Wood as well as work by the artists Briton Rivière, Joseph Wolf and A.D. May. It also included portraits by the Swedish photographer Oscar Rejlander (1813–1875), anatomical diagrams by Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842) and Friedrich Henle (1809–1885), as well as illustrational quotations from the Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine (1862) by the French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875).[24] As a result of his domestic psychology experiments, Darwin reduced the number of commonly observed emotions from Duchenne's calculation of more than sixty emotional expressions, to just six "core" expressions: anger, fear, surprise, disgust, happiness and sadness.

Darwin received dozens of photographs of psychiatric patients from James Crichton-Browne, but included in the book only one engraving (photoengraved by James Davis Cooper) based on these illustrations – sent on 6 June 1870 (along with Darwin's copy of Duchenne) (Darwin Correspondence Project: Letter 7220). This was Figure 19, page 296 – and showed a patient under the care of Dr James Gilchrist at the Southern Counties Asylum (of Scotland), the public wing of the Crichton Royal in Dumfries.

I have been making immense use almost every day of your manuscript – the book ought to be called by Darwin and Browne....

— Charles Darwin to James Crichton Browne

Reception

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2013) |

Contemporary

The review in the January 1873 Quarterly Journal of Science concluded that "although some parts are a little tedious, from the amount of minute detail required, there is throughout so much of acute observation and amusing anecdote as to render it perhaps more attractive to general readers than any of Mr. Darwin's previous work".[25]

Modern

Eric Korn, in the London Review of Books, describes how the book was claimed, and he argues subverted, by Margaret Mead and her "sympathisers", and then presented afresh by Paul Ekman, who had himself collected pro-Darwin, anti-Mead evidence, Korn writes, for the universality of human facial expression of emotions. Darwin, suggests Korn, cunningly avoided unsettling the Victorian public by arguing that humans had "animal traits", and instead charmed them by telling stories of "human traits in animals", avoiding too much explicit talk of natural selection at work, preferring, Korn thinks, to leave the Darwinian implication hanging. Korn points out that the book has never been out of print since 1872, giving the lie to Ekman's talk of "Darwin's lost masterpiece".[26]

The "Editor's notes" at the "Mead Project source page" on the book comment that

Darwin's book ... is among the most enduring contributions from 19th century psychology. The ideas expressed in its pages have persisted, for better or worse, down through the present, in one form or another. Although premised on an unsupportable interpretation of the nature of "expression," it is this idea that permeates the majority of work on emotional experience within psychology... Dewey's critique of Darwin's principles provides no small part of the foundations on which functionalist psychology is built. Similarly, the work plays a very large part in George Herbert Mead's discussion of the formation of significant symbols, as outlined in the early chapters of Mind, Self and Society. As Dewey notes, the arguments presented by Darwin may be wrong, but they are compelling.[27]

Publication

Darwin concluded work on the book with a sense of relief. The proofs, tackled by his daughter Henrietta ("Ettie") and son Leo, required a major revision which made Darwin "sick of the subject and myself, and the world".[28]

It quickly sold around 7,000 copies and was widely praised as a charming and accessible introduction to Darwin's evolutionary theories.[29]

A second edition was published by Darwin's son in 1889, without several revisions suggested by Darwin; these were not published until the third edition of 1999 (edited by Paul Ekman).[30]

Influence

The lavish style of biological illustration[31] was followed in work on animal locomotion by photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904)[32] and the Scottish naturalist James Bell Pettigrew[33][34] (1832–1908); in the extensively (and unreliably) illustrated works of the evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel; and – to a lesser extent – in D'Arcy Thompson's On Growth and Form (1917).[35]

Darwin's ideas were followed up in William James' What Is An Emotion ? (1884) and Walter Cannon's Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage (1915)[36] – in which Cannon coined the famous phrase fight or flight response. On 24 January 1895, James Crichton-Browne delivered a notable lecture in Dumfries, Scotland On Emotional Expression, presenting some of his reservations about Darwin's views.[37] In 1905, Sir Arthur Mitchell, a psychiatrist who had served as William A.F. Browne's deputy in the Scottish Lunacy Commission, published About Dreaming, Laughing and Blushing, bridging Darwin's concerns with those of psychoanalysis. In 2003, the New York Academy of Sciences published Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, a compendium of 37 papers with current research on the subject.

"George Herbert was wrong when he said that man was all symmetry; it was woman to whom that remark applied....evolution is still going on, and the faces of men and women still altering, for the better, every day. The emotions are less violently expressed....our ancestors gave vent to their feelings in a way that we would be ashamed of, and their range of feeling seems to have been in some degree more limited. The language of the countenance, like that of the tongue, has been enriched in the process of the suns...."

— James Crichton-Browne, On Emotional Expression, being The Presidential Address, Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society (Thursday, 24th January 1895)

"All these sensations and innervations belong to the field of The Expression of the Emotions, which, as Darwin (1872) has taught us, consists of actions which originally had a meaning and served a purpose. These may now for the most part have become so much weakened that the expression of them in words seems to us to be only a figurative picture of them, whereas in all probability the description was once meant literally; and hysteria is right in restoring the original meaning of the words...."

— Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, Studies on Hysteria (1895)

Freud's early publications on the symptoms of hysteria (with his influential concept of unconscious emotional conflict) acknowledged debts to Darwin's work on emotional expression.[38] Darwin's impact on psychoanalysis is discussed in detail by Lucille Ritvo.[39] Constitutional (psychosomatic) theories of personality were later elaborated by Paul Schilder[40] (1886 - 1940) with his notion of the body image, by the psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer and in the (now largely discredited) somato-typology of W H Sheldon (1898 - 1977). The biology of the human emotions was further explored by Desmond Morris in his (richly illustrated) popular scientific book Manwatching.[41]

See also

References

- ^ Darwin Charles, Ekman Paul, Prodger Phillip (1998) The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 3rd edn, London: Harper Collins.

- ^ a b Barrett 1980

- ^ Barrett 1980, p. xviii

- ^ Ospovat, Dov (1981) The Development of Darwin's Theory Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1991) One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the genesis of modern evolutionary thought Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press

- ^ Barrett 1980, pp. 6–37

- ^ Browne, E. Janet (1995) Charles Darwin: Voyaging, London: Jonathan Cape, pp 383 – 384.

- ^ Barrett 1980, p. xix

- ^ Pearn, Alison M. (2010) "This Excellent Observer..." : the Correspondence between Charles Darwin and James Crichton-Browne, 1869 – 75, History of Psychiatry, 21, 160 – 175

- ^ see, for example, Ekman's textual commentary in Darwin, Ekman, Prodger (1998) The Expression of the Emotions, 3rd edition, pages 45 and 54.

- ^ Desmond, Adrian (1982) Archetypes and Ancestors: Palaeontology in Victorian London 1850 – 1875 Chicago: Chicago University of Chicago Press, pp 116 – 121

- ^ Desmond, Adrian (1989) The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine and Reform in Radical London Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ^ Stott, Rebecca (2003) Darwin and the Barnacle London: Faber and Faber

- ^ Boulter, Michael (2006) Darwin's Garden: Down House and the Origin of Species London: Constable

- ^ Bowlby, John (1990) Charles Darwin, A Biography London: Hutchinson.

- ^ Bell, Charles (1806) Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting London:

- ^ Bell, Charles (1824) Essays on the Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression London: John Murray

- ^ Bowlby, pp. 6 – 14

- ^ Hartley, Lucy (2001) Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth Century Culture Cambridge University Press

- ^ Walmsley, Tom (1993) Psychiatry in Descent: Darwin and the Brownes, Psychiatric Bulletin, 17, 748 - 751

- ^ Maudsley, Henry (1870) Body And Mind: The Gulstonian Lectures for 1870 London: Macmillan and Co.

- ^ Phillip Prodger Curator of Photography Peabody Essex Museum (29 August 2009). Darwin's Camera : Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-0-19-972230-3. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

Heliotype was a new photomechanical method of reproduction invented by the photographer Ernest Edwards (1837–1903), for whom Darwin had sat for a portrait in 1868. Although he had no experience in photographic publishing, Darwin suggested this new technique to John Murray. ... heliotype reduced the cost of production considerably, enabling Darwin to afford the unprecedented number of photographs appearing in Expression.

- ^ Charles Darwin (9 April 1998). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Oxford University Press. pp. 401–. ISBN 978-0-19-977197-4. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

Darwin's English publisher, John Murray, was at first opposed to the idea of using photographs to illustrate the book. He advised Darwin that the inclusion of photographs would make Expression a money- losing proposition

- ^ Duchenne (de Boulogne), G.-B., (1990) The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression by Guillaume-Benjamin (Amand) Duchenne de Boulogne edited and translated by R. Andrew Cuthbertson, Cambridge University Press and Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L'Homme, originally published (1862) Paris: Éditions Jules Renouard, Libraire

- ^ Anon (January 1873). "Darwin's "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals"". Quarterly Journal of Science: 113–118.

- ^ Korn, Eric (November 1998). "How far down the dusky bosom?". London Review of Books. 20 (23): 23–24.

- ^ c/o Ward, Lloyd Gordon (2007). "A Mead Project Source Page: The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animal". The Mead Project, Brock University, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Frederick Burkhardt; Sydney Smith; David Kohn; William Montgomery (10 March 1994). A Calendar of the Correspondence of Charles Darwin, 1821–1882. Cambridge University Press. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-0-521-43423-2.

To [Leonard Darwin] 29 July [1872] [Down] CD cannot improve style [of Expression] without great changes. 'I am sick of the subject, and myself, and the world'.

- ^ Keith Francis (2007). Charles Darwin and The Origin of Species. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-313-31748-4.

1872 19 February: Sixth edition of The Origin of Species is published (3,000 copies printed). [63] 26 November: The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is published (7,000 copies printed; 5,267 sold). 1874 Second edition of The ...

- ^ Black, J (June 2002), "Darwin in the world of emotions" (Free full text), Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 95 (6): 311–3, doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.6.311, ISSN 0141-0768, PMC 1279921, PMID 12042386

- ^ Prodger, Phillip (2009) Darwin's Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution Oxford University Press

- ^ Prodger, Phillip (2003) Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the instantaneous photography movement The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts, Stanford University, in association with Oxford University Press

- ^ Pettigrew, James Bell (1874) Animal Locomotion, or, Walking, Swimming and Flying, with a dissertation on Aeronautics New York: D. Appleton and Co.

- ^ Pettigrew, James Bell (1908) Design in Nature, 3 vols, London: Longman

- ^ Smith, Jonathan (2006) Charles Darwin and Victorian Visual Culture Cambridge University Press, especially pp. 179 – 243

- ^ Cannon, Walter B. (1915) Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage – An Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Excitement New York: D. Appleton and Co.

- ^ [Crichton-Browne, James] (1895) Conversazione, - and the Presidential Address – "On Emotional Expression", Transactions and the Journal of Proceedings of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, Series II, 11, pp 72–77, Dumfries: The Courier and Herald Offices

- ^ Sulloway, Frank J. (1979) Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend London: Burnett Books/Andre Deutsch

- ^ Ritvo, Lucille B. (1990) Darwin's Influence on Freud: A Tale of Two Sciences New Haven and London: Yale University Press

- ^ Schilder, Paul (1950) The Image and Appearance of the Human Body: Studies in the Constructive Energies of the Psyche New York: International Universities Press

- ^ Morris, Desmond (1978) Manwatching: A Field Guide To Human Behaviour London: Triad Panther.

Sources

- Barrett, Paul (1980), Metaphysics, Materialism, & the evolution of mind: the early writings of Charles Darwin, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-13659-0,

Early writings of Charles Darwin. With a commentary by Howard E. Gruber

External links

- Freeman, R. B. (1977), The Works of Charles Darwin: An Annotated Bibliographical Handlist (2nd ed.), Folkstone: Dawson.

- Darwin, Charles (1872), The expression of the emotions in man and animals, London: John Murray.

- Ekman, Paul (editor) (2003), Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1st ed.), New York: New York Academy of Sciences

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help).

Free e-book versions: