The Train (1964 film)

| The Train | |

|---|---|

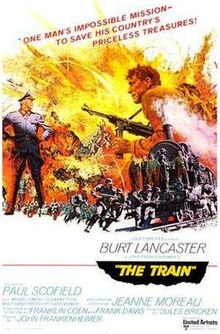

Movie poster by Frank McCarthy | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Written by | Story & screenplay: Franklin Coen Frank Davis Uncredited: Walter Bernstein Howard Dimsdale Nedrick Young |

| Produced by | Jules Bricken |

| Starring | Burt Lancaster Paul Scofield Jeanne Moreau Michel Simon |

| Cinematography | Jean Tournier Walter Wottitz |

| Edited by | David Bretherton |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates | 1964 (UK) March 7, 1965 (U.S.) |

Running time | 140 minutes (UK) 133 minutes (U.S.) |

| Countries | United States France Italy |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $6.8 million[1] |

The Train is a 1964 war film directed by John Frankenheimer from a story and screenplay by Franklin Coen and Frank Davis, inspired by the non-fiction book Le front de l'art by Rose Valland, who documented the works of art placed in storage that had been looted by the Germans from museums and private art collections. It stars Burt Lancaster, Paul Scofield and Jeanne Moreau.

Set in August 1944, the film, shot in black-and-white, sets French Resistance-member Paul Labiche (Lancaster) against German Colonel Franz von Waldheim (Scofield), who is attempting to move stolen art masterpieces by train to Germany. Inspiration for the scenes of the train's interception came from the real-life events surrounding train No. 40,044 as it was seized and examined by Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg of the Free French forces outside Paris.

Plot

In 1944, masterpieces of modern art stolen by the Wehrmacht are being shipped to Germany; the officer in charge of the operation, Colonel Franz von Waldheim (Paul Scofield), is determined to take the paintings to Germany, no matter the cost. After the works chosen by Waldheim are removed from the Jeu de Paume Museum, curator Mademoiselle Villard (Suzanne Flon) seeks help from the French Resistance. Given the imminent liberation of Paris by the Allies, they need only delay the train for a few days, but it is a dangerous operation and must be done in a way that does not risk damaging the priceless cargo.

Although Resistance cell leader and SNCF area inspector Paul Labiche (Burt Lancaster) initially rejects the plan, telling Mlle. Villard and senior Resistance leader Spinet (Paul Bonifas), "I won't waste lives on paintings," he has a change of heart after a cantankerous elderly engineer, Papa Boule (Michel Simon), is executed for trying to sabotage the train on his own. After that sacrifice, Labiche joins his Resistance teammates Didont (Albert Rémy) and Pesquet (Charles Millot), who have been organizing their own plan to stop the train with the help of other SNCF Resistance members. They devise an elaborate ruse to reroute the train, temporarily changing railway station signage to make it appear to the German escort as if they are heading to Germany when they have actually turned back toward Paris. They then arrange a double collision in the small town of Rive-Reine that will block the train without risking the cargo. Labiche, although shot in the leg, escapes on foot with the help of the widowed owner of a Rive-Reine hotel, Christine (Jeanne Moreau), while other Resistance members involved in the plot are executed.

The night after the collision, Labiche and Didont meet Spinet again, along with young Robert (the nephew of Jacques, the executed Rive-Reine station master) and plan to paint the tops of three wagons white to warn off Allied aircraft from bombing the art train. Robert recruits railroad workers and friends of his Uncle Jacques from nearby Montmirail, but the marking attempt is discovered, and Robert and Didont are both killed.

Now working alone, Labiche continues to delay the train after the tracks are cleared, to the mounting rage of von Waldheim. Finally, Labiche manages to derail the train without endangering civilian hostages that the colonel has placed on the locomotive to prevent it being blown up. Von Waldheim flags down a retreating army convoy and learns that a French armoured division is not far behind. The colonel orders the train unloaded and attempts to commandeer the trucks, but the officer in charge refuses to obey his orders. The train's small German contingent kills the hostages and joins the retreating convoy.

Von Waldheim remains behind with the abandoned train. Crates are strewn everywhere between the tracks and the road, labelled with the names of famous artists. Labiche appears and the colonel castigates him for having no real interest in the art he has saved:

Does it please you, Labiche? You feel a sense of excitement at just being near them? A painting means as much to you as a string of pearls to an ape. You won by sheer luck. You stopped me without knowing what you were doing or why.... The paintings are mine. They always will be. Beauty belongs to the man who can appreciate it. They will always belong to me, or a man like me. Now, this minute, you couldn't tell me why you did what you did.

In response, Labiche turns and looks at the murdered hostages. Then, without a word, he turns back to von Waldheim and shoots him. Afterwards he limps away, leaving the corpses and the art treasures where they lie.

Cast

- Burt Lancaster as Paul Labiche

- Paul Scofield as Col. Franz von Waldheim Template:Nb10

- Jeanne Moreau as Christine

- Suzanne Flon as Mademoiselle Villard

- Michel Simon as Papa Boule

- Wolfgang Preiss as Maj. Herren

- Albert Rémy as Didont

- Charles Millot as Pesquet

- Richard Münch as Gen. von Lubitz

- Jacques Marin as Jacques

- Paul Bonifas as Spinet

- Arthur Brauss as Lt. Pilzer

- Jean Bouchaud as Capt. Schmidt

- Donald O'Brien as Sgt. Schwartz

- Howard Vernon as Capt. Dietrich

Historical background

The Train is based on the factual 1961 book Le front de l'art by Rose Valland, the art historian at the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, who documented the works of art placed in storage there that had been looted by the Germans from museums and private art collections throughout France and were being sorted for shipment to Germany in World War II.

In contrast to the action and drama depicted in the film, the shipment of art that the Germans were attempting to take out of Paris on 1 August 1944 was held up by the French Resistance with an endless barrage of paperwork and red tape and made it no farther than a railyard a few miles outside Paris.[2]

The train's actual interception was inspired by the real-life events surrounding train No. 40,044 as it was seized and examined by Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg of the Free French forces outside Paris in August 1944. Upon his soldiers opening the wagon doors he viewed many plundered pieces of art that had once been displayed in the home of his father, Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg, one of the world's major Modern art dealers.[3]

German veterans' organisations, including the SS veterans' group HIAG, objected to Wehrmacht soldiers being depicted executing hostages and Resistance members in the film. They said that SS or uniformed Sicherheitspolizei (the Sicherheitsdienst and Gestapo) personnel should have been used for those scenes.[citation needed]

Production

John Frankenheimer took over the film from another director, Arthur Penn. The Train had already begun shooting in France when star Burt Lancaster had Penn fired and called in Frankenheimer to take over the film. Penn envisioned a more intimate film that would muse on the role art played in Lancaster's character, and why he would risk his life to save the country's great art from the Nazis. He did not intend to give much focus to the mechanics of the train operation itself. But Lancaster wanted more emphasis on action to ensure that the film would be a hit, after the failure of his film The Leopard. The production was shut down briefly while the script was rewritten, and the budget doubled under Frankenheimer's direction. As he recounts in the Champlin book, Frankenheimer used the production's desperation to his advantage in negotiations. He demanded and got the following: his name was made part of the title, "John Frankenheimer's The Train"; the French co-director, demanded by French tax laws, was not allowed to ever set foot on set; he was given total final cut; and a Ferrari.[4] Much of the film was shot on location.

The Train contains multiple real train wrecks. The Allied bombing of a rail yard was accomplished with real dynamite, as the French rail authority needed to enlarge the track gauge. This can be observed by the shockwaves travelling through the ground during the action sequence. Producers realized after filming that the story needed another action scene, and reassembled some of the cast for a Spitfire attack scene that was inserted into the first third of the film. French Armée de l'Air Douglas A-26 Invaders are also seen later in the film.[5]

The film includes a number of sequences involving long tracking shots and wide-angle lenses, with both foreground and background action in focus. Noteworthy tracking shots include:

- Labiche attempting to flag down a train, then sliding down a ladder, running along the tracks and jumping onto the moving locomotive—performed by Lancaster himself, not a stunt double;

- A scene in which the camera wanders around Nazi offices that are hastily being cleared, eventually focusing on von Waldheim and following him back through the office;

- A long dolly shot of von Waldheim travelling through a marshalling yard at high speed on a motorbike;

- Labiche rolling down a mountain and across a road, and staggering down to the track. Frankenheimer noted on his DVD commentary that Lancaster performed the entire roll down the mountain himself, filmed by cameras at points along the hillside.

During an interview with the History Channel, Frankenheimer revealed:

- The marshalling yard attacked during the Allied bombing raid sequence was demolished by special arrangement with the French railway, which had been looking to do it but had lacked funding.

- The sequence in which Labiche is shot and wounded by German soldiers while fleeing across a pedestrian bridge was necessitated by a knee injury Lancaster suffered during filming - he stepped in a hole while playing golf, spraining his knee so severely that he could not walk without limping.

- When told that Michel Simon would be unable to complete scenes scripted for his character as a result of prior contractual obligations, Frankenheimer devised the sequence wherein Papa Boule is executed by the Germans. Jacques Marin's character was killed for similar reasons.

- Colonel von Waldheim (Paul Scofield) is told, at the scene of the last major train wreck, by Major Herren (Wolfgang Preiss), "This is a hell of a mess you've got here, Colonel." This line became a metaphor for complicating disasters on Frankenheimer films thereafter.

- Colonel von Waldheim was originally to engage Labiche in a shootout at the film's climax, but after Paul Scofield was cast in the role, at Lancaster's suggestion Frankenheimer re-wrote the scene to provide Scofield a more suitable end—taunting Labiche into killing him.

Frankenheimer remarked on the DVD commentary, "Incidentally, I think this is the last big action picture ever made in black and white, and personally I am so grateful that it is in black and white. I think the black and white adds tremendously to the movie."

Throughout the film, Frankenheimer often juxtaposed the value of art with the value of human life. A brief montage ends the film, intercutting the crates full of paintings with the bloodied bodies of the hostages, before a final shot shows Labiche walking away.[6]

Film locations

Filming took place in several locations, including: Acquigny, Calvados; Saint-Ouen, Seine-Saint-Denis; and Vaires, Seine-et-Marne. The shots span from Paris to Metz. Much of the film is centered in the fictional town called "Rive-Reine."

The circular journey

Actual train route: Paris, Vaires, Rive-Reine, Montmirail, Chalon-S-Marne, St Menehould, Verdun, Metz, Pont-a-Mousson, Sorcy (Level Crossing), Commercy, Vitry Le Francois, Rive-Reine.

Planned route from Metz to Germany: Remilly, Teting (Level Crossing), St Avold, Zweibrücken.

Locomotives used

The locomotives used were the former Chemins de fer de l'Est Series 11s 4-6-0s, which the SNCF classified as 1-230.B. Identifiable locomotives include 1-230.B.739 with tender 22.A.739, 1-230.B.616, and 1-230.B.855 with tender 22.A.886; Papa Boule's locomotive is 1-230.B.517; and SNCF Class 030TUs can be seen in background shots. In the crash scene, an ancient "Bourbonnais" type 0-6-0 (N° 757) is used to block the line. In the yard scenes, some SNCF Class 141R engines can be seen parked on sidings, however, engines of this class were not built until after the war as part of the railway's reconstruction.

Reception

The Train earned $3 million in the US and $6 million elsewhere.[7] It had cost $6.7 million.[8] The film was one of the 13 most popular films in the UK in 1965.[9]

The Train holds a 100% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes (although it does show one negative review),[10] and a score of 7.9/10 on the Internet Movie Database.[11]

Awards and honors

- Nominated for the 1964 film award of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts.[12]

- Nominated for the 1965 Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay (story and screenplay written directly for the screen).[13]

- Included in the second edition of The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made, published in 2004.[14]

See also

- The Train: Escape to Normandy, a 1987 video game loosely based on this film.

- The Monuments Men, a 2014 film about an Allied group tasked with saving pieces of art and culturally important items from destruction by Hitler during World War II.

References

Notes

- ^ a b "The Train, Box Office Information." The Numbers. Retrieved: January 22, 2013.

- ^ "DVD enclosure booklet: The Train". MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia and Tom Mashberg. "Family, 'Not Willing to Forget,' Pursues Art It Lost to Nazis". The New York Times, April 27, 2013, p. A1; published online April 26, 2013. Retrieved: April 27, 2013.

- ^ Mackieon, Drew. "Nine Reasons to Watch The Train." KCET presents, December 18, 2011. Retrieved: November 22, 2012.

- ^ Swanson, August. "The Douglas A/B-26 Invader Film Stars." napoleon130.tripod.com. Retrieved: April 20, 2011.

- ^ Evans 2000, p. 187.

- ^ Balio 1987, p. 279.

- ^ Buford 2000, p. 240.

- ^ "Most Popular Film Star." The Times [London, England], December 31, 1965, p. 13 via The Times Digital Archive, September 16, 2013.

- ^ "The Train." Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved: October 3, 2016.

- ^ "The Train (1964)." IMDb. Retrieved: November 22, 2012.

- ^ "Winners and Nominees 1960–69." bafta.org. Retrieved: November 22, 2012.

- ^ "The Train." awardsdatabase.oscars.org. Retrieved: November 22, 2012.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made." The New York Times, April 29, 2003. Retrieved: May 25, 2010

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Stephen B. Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007. ISBN 978-0-78643-145-8.

- Balio, Tino. United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-29911-440-4.

- Buford, Kate. Burt Lancaster: An American Life. New York: Da Capo, 2000. ISBN 0-306-81019-0.

- Champlin, Charles, ed. John Frankenheimer: A Conversation With Charles Champlin. Bristol, UK: Riverwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-880756-09-6.

- Evans, Alun. Brassey's Guide to War Films. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books Inc., 2000. ISBN 978-1-57488-263-6.

- Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of John Frankenheimer (The International Film Guide Series). New York: Zwemmer/Barnes, 1969. ISBN 978-0-49807-413-4.

External links

- The Train at IMDb

- The Train at the TCM Movie Database

- The Train at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Train at AllMovie

- 1960s war films

- 1964 films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- French black-and-white films

- Italian black-and-white films

- English-language films

- Film scores by Maurice Jarre

- Films about the French Resistance

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films directed by John Frankenheimer

- Films set in 1944

- Films set in Paris

- Films set on trains

- French films

- Italian films

- Rail transport films

- United Artists films

- War adventure films

- Western Front of World War II films

- Screenplays by Walter Bernstein