The War of the Worlds

| Author | Herbert George Wells |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | William Heinemann |

Publication date | 1898 |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover & Paperback) & E-book |

| Pages | 303 pp (May change depending on the publisher and the size of the text) |

| ISBN | N/A Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

The War of the Worlds (1898) is a science fiction novel by H. G. Wells, describing an invasion of late Victorian England by Martians equipped with advanced weaponry. It is a seminal depiction of an alien invasion of Earth.

The novel is narrated by an anonymous journalist, living where the invaders land. Throughout the narrative he struggles to reunite with his wife and brother, while witnessing the Martians destroying Southern English counties and London. Finding London an abandoned ruin, and seeing little hope for humankind, he decides to sacrifice himself to the invaders, only to discover that they have succumbed to the effects of Earth bacteria, to which they have no immunity.

The plot has been related to invasion literature of the time. The novel has been variously interpreted as a commentary on evolutionary theory, British imperialism, and generally Victorian fears and prejudices. At the time of publication it was classed as a scientific romance. Since then, it has influenced much literature and other media, spawning several films, radio dramas, comic book adaptations, a television series, and sequels or parallel stories by other authors.

Plot

The narrator is at an observatory in Ottershaw when explosions are witnessed on Mars, causing interest among the scientific community. Later a "meteor" lands on Horsell Common, South West of London, close to the narrator's home. He is among the first to discover that the object is a space-going artificial cylinder. When the cylinder opens, the Martians—bulky, octopus-like creatures the size of a bear— briefly emerge, show difficulty in coping with the Earth's atmosphere, and rapidly retreat into the cylinder. A human deputation moves towards the cylinder, but the Martians incinerate them with a heat-ray weapon, before beginning the construction of alien machinery.

After the attack, the narrator takes his wife to Leatherhead to stay with relatives until the threat is eliminated. Upon returning home, he discovers the Martians have assembled towering three-legged "fighting-machines" armed with a heat-ray and a chemical weapon: "the black smoke". These Tripods easily defeat army units positioned around the crater and proceed to attack surrounding communities. Fleeing the scene, the narrator meets a retreating artilleryman, who tells him that another cylinder has landed between Woking and Leatherhead, cutting the narrator off from his wife. The two men try to escape together, but are separated at the Shepperton to Weybridge Ferry during a Martian attack on Shepperton.

More cylinders land across southern England, and a panicked flight out of London begins, including the narrator's brother. The torpedo ram HMS Thunder Child destroys two tripods before being sunk by the Martians, though this allows the ship carrying the Narrator's brother, and his two female companions to escape. Shortly after, all organized resistance has ceased, and the Tripods roam the shattered landscape unhindered. Red weed, a fast growing Martian form of vegetation spreads over the landscape, aggressively overcoming the Earth's ecology, in much the same way the Martians have overcome human civilization.

The narrator takes refuge in a ruined building shortly before a Martian cylinder lands nearby, trapping him with an insane curate, who has been traumatized by the invasion and believes the Martians to be satanic creatures heralding the advent of Armageddon. For several days, the narrator desperately tries to calm the clergyman, and avoid attracting attention, while witnessing the Martians feeding on humans by direct blood transfusion. Eventually the curate's evangelical outbursts lead the Martians to their hiding place, and while the Narrator escapes detection, the clergyman is dragged away.

The Martians eventually depart, and the Narrator heads towards Central London. En route he once again encounters the artilleryman who has plans to rebuild civilization underground, but their quixotic nature is shown by the slow progress of an unimpressive trench the artilleryman has been digging. The Narrator heads into a deserted London, finally decides to give up his life by rushing towards the Martians, only to discover they, along with the Red Weed, have succumbed to terrestrial pathogenic bacteria, to which they have no immunity. At the conclusion, the Narrator is unexpectedly reunited with his wife, and they, along with the rest of humanity, are faced with a new and expanded universe as a result of the invasion.

Style

The War of the Worlds is written in a journalistic style, as if a factual account of the invasion, which helps to make the story plausible. The chapter headings are also similar to newspaper headlines. The narrator is a middle class scientific journalist living in Woking, south west of London, characteristics which make him very similar to Wells himself at the time of writing. The Narrator describes most of the events from first hand observation, often with precise and scientific detail, but also reports events later told to him by his younger brother, to provide a wider perspective on the invasion. The Narrator and his brother are not named, neither are the key characters of the artilleryman and the curate. [1]

Writing and setting

While The War of the Worlds is a work of science fiction, much of its setting and premise was grounded in scientific ideas of the time, actual locations in Southern England and aspects of Wells' everyday life in the 1890s.

Scientific setting

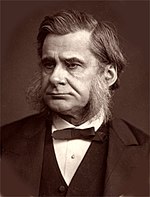

Wells trained as a science teacher during the later half of the 1880s. One of his teachers was T.H Huxley, famous as a major advocate of Darwinism. He later taught science, his first book was a biology textbook and he joined the scientific journal Nature as a reviewer in 1894. [2][3] Much of his work is notable for making contemporary ideas of science and technology easily understandable to readers. [4]

The scientific fascinations of the novel are established in the opening chapter, where the Narrator views Mars through a telescope, and Wells offers the image of the superior Martians having observed human affairs, as through watching tiny organisms through a microscope. Ironically, it is microscopic Earth lifeforms that finally prove deadly to the invasion force.[5] In 1894 a French astronomer observed a 'strange light' on Mars, and published his findings in the scientific journal Nature on 2 August of that year. Wells used this observation to open the novel, imagining these lights to be the launching of the Martian cylinders towards Earth. American Astronomer Percival Lowell published the book Mars, in 1895, suggesting features of the planet’s surface observed through telescopes might be canals. He speculated that these might be irrigation channels constructed by a sentient life form to support existence on an arid, dying world, similar to that Wells suggests the Martians have left behind. [1][6] The novel also presents ideas related to Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, both in specific ideas discussed by the Narrator, and themes explored by the story.

Wells, himself, wrote an essay entitled 'Intelligence on Mars', published in 1896 in the Saturday Review which sets out many of the ideas for the Martians and their planet, which are used almost unchanged in The War of the Worlds.[1] In the essay he speculates about the nature of the Martian inhabitants, how their evolutionary progress might compare to humans, and also suggests that Mars, being an older world than the Earth, might have become frozen and desolate, conditions that might encourage the Martians to find another planet on which to settle. [7]

Physical location

In 1895, Wells was an established writer and he married his second wife, Catherine Robbins, moving with her to the town of Woking in Surrey. Here he spent his mornings walking or cycling in the surrounding countryside, and his afternoons writing. The original idea for The War of the Worlds came from his brother, during one of these walks, pondering on what it might be like if alien beings were to suddenly descend on the scene and start attacking its inhabitants.[8]

Much of the The War of the Worlds takes place around Woking and nearby suburbs. The initial landing site of the Martian invasion force, Horsell Common, was an open area close to Wells' home. In the preface to the Atlantic edition of the novel, he wrote of his pleasure in riding a bicycle around the area, and imagining the destruction of cottages and houses he saw, by the Martian heat-ray or the red weed.[1] While writing the novel, Wells enjoyed shocking his friends by revealing details of the story, and how it was bringing total destruction to parts of the South London landscape that were familiar to them. The characters of the artilleryman, the curate and the medical student were also based on acquaintances in Woking and Surrey.[9]

In the present day, a 7 meter (23 feet) high sculpture of a tripod fighting machine, entitled 'The Martian', based on the description in The War of the Worlds, stands in Crown Passage, close to the local railway station, in Woking.[10]

Cultural setting

His depiction of suburban late Victorian culture in the novel, was an accurate reflection of his own experiences at the time of writing. [11] In the late 19th Century the British Empire was the predominant colonial and military power on the globe, making its domestic heart a poignant and terrifying starting point for an invasion by aliens with their own imperialist agenda. [12] He also drew upon a common fear which had emerged in the years approaching the turn of the century, known at the time as Fin de siècle or 'end of the age', which anticipated apocalypse at midnight on the last day of 1899. [9]

Publication

In the late 1890s it was common for novels, prior to full volume publication, to be serialized in magazines or newspapers, with each part of the serialization ending upon a cliff hanger to entice audiences to buy the next edition. This is a practice familiar from the first publication of Charles Dickens' novels in the nineteenth century. The War of the Worlds was first published in serialized form in Pearson's Magazine in 1897. [13] Wells was paid ₤200 and Pearsons demanded to know the ending of the piece before committing to publish.[14]

The complete volume was published by William Heinemann in 1898 and has been in print ever since.

An unauthorized serialization of the novel was published in the United States prior to this, in New York in 1897.[15] A pirated version involving the Martians landing in New England was published by the Boston Post in 1898, Wells protested against this.[2]

Reception

The War of the Worlds was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. There was however some criticism of the brutal nature of the events in the narrative. [16]

Relation to invasion literature

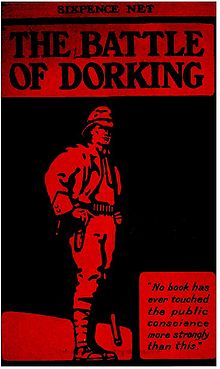

Between 1871 and 1914 over 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was The Battle of Dorking (1871) by George Tomkyns Chesney, an army officer. The book portrays a surprise German attack, with a landing on the South coast of England, made possible by the distraction of the Royal Navy in colonial patrols and the army in an Irish insurrection. The German army makes short work of English Militia and rapidly marches to London. The story was published in Blackwood's Magazine in May 1871, and so popular that it was reprinted a month later as a pamphlet which sold 80,000 copies.[17][18]

The appearance of this literature, much of which might be viewed as contemporary propaganda, reflected the increasing feeling of anxiety and insecurity as international tensions between European Imperial powers escalated towards the outbreak of the First World War. Across the decades, the nationality of the invaders tended to vary, according to the most acutely perceived threat at the time. In the 1870s, the Germans were the most common invaders. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a period of strain on Anglo-French relations, and the signing of a treaty between France and Russia, the French became the more common menace. [17][18]

There are a number of plot similarities between Wells' book and The Battle of Dorking. In both books, a ruthless enemy makes a devastating surprise attack, with the British armed forces helpless to stop its relentless advance and both involve the destruction of the Home Counties of southern England.[18] However, The War of the Worlds transcends the typical fascination of Invasion Literature with European politics, the suitability of contemporary military technology to deal with the armed forces of other nations, and international disputes, with its introduction of an alien adversary.[19]

Although much of Invasion Literature may have been less sophisticated and visionary than Wells' novel, it was a useful, familiar genre to support the publication success of the piece, attracting readers used to such tales. It may also have proved an important foundation for Wells' ideas, as he had never seen or fought in a war.[20]

Scientific predictions and accuracy

Mars

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo scientific ideas of the time, including Pierre-Simon Laplace's nebular hypothesis, Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, and Gustav Kirchhoff's theory of Spectroscopy. These scientific ideas combined to present the possibility that planets are alike in composition and conditions for the development of species, which would likely lead to the emergence of life at a suitable geological age in a planet's development.[21]

By the time Wells came to write The War of the Worlds, there had been three centuries of observation of Mars through telescopes. Galileo, in 1610, observed the planet's phases and in 1666 Giovanni Cassini identified the polar ice caps.[6] In 1878, Italian astronomer, Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli observed geological features which he called canali (Italian for "channels"). This was mistranslated into the English as "canals" which, being artificial watercourses, fueled the belief that there was some sort of intelligent extraterrestrial life on the planet. It has been suggested in recent years, that the canals were actually the result of a disease that made Giovanni see his own eye structure which he assumed were canals. This further influenced American astronomer Percival Lowell.[22]

In 1895 Lowell published a book entitled Mars which speculated about an arid, dying landscape, whose inhabitants had been forced to build canals thousands of miles long to bring water from the polar caps to irrigate the remaining arable land. This formed the most advanced scientific ideas about the conditions on the red planet available to Wells at the time War of the Worlds was written. The concept of canals with flowing water was later proved erroneous by more accurate observation of the planet, and later landings by Russian and American probes such as the two Viking missions which found a lifeless world too cold for water to exist in its liquid state.[6]

Space travel

The Martians travel to the Earth in cylinders, apparently fired from a huge space gun on the surface of Mars. This was a common representation of space travel in the nineteenth Century, and had also been used by Jules Verne in From the Earth to the Moon. Modern scientific understanding renders this idea impractical, as it would be difficult to control the trajectory of the gun precisely, and the force of the explosion necessary to propel the cylinder from the Martian surface to the Earth would likely kill the occupants.[23] It bears similarity to the modern spacecraft propulsion concept of mass drivers.

Total war

The Martian invasion proceeds with total disregard for human life; attacks on people and their environment are conducted with the heat-ray, with poisonous gas, the Black Smoke, delivered by rockets, and the Red Weed. These weapons brought almost total destruction to the capital of the British Empire and its surrounding counties. It also involves the strategic destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways and telegraph lines. It appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, terrorizing and leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth Century progressed, particularly from the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of 'surgical strikes' on key military and civilian targets.[24]

Wells' vision of a war bringing total destruction without moral limitations in The War of the Worlds were not taken seriously by readers at the time of publication. It was seen as one of a number of fictions which proposed this idea. He later expanded these ideas with more realistic novels such as When the Sleeper Awakes (1899), The War in the Air (1908) and The World Set Free (1914). This kind of 'total war' did not become fully realised until the Second World War, with the Nazi Blitzkrieg, the terrorizing and evacuation of entire civilian populations, and the annihilation of cities.[25]

Weapons and armour

Wells' description of chemical weapons - the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to murder human beings en masse - was later a reality during the First World War, with the use of Mustard Gas.[13] The rockets used by the Martians to deliver the Black Smoke are conceptual precursors of FROGs (Free Rocket Over Ground), rockets with chemical warheads, which were a key strategic weapon in Soviet attack plans for the invasion of Europe. The Heat-Ray, used by the Martians to annihilate nineteenth century military technology, and cause widespread devastation, is a precursor to the concept of laser weaponry, now widely familiar. Comparison between lasers and the Heat-Ray was made as early as the later half of the 1950s when lasers were still in development. Prototypes of mobile laser weapons have been developed and it is now being researched and tested as a possible future weapon in space. [24]

Military theorists of the era, including the Royal Navy prior to the First World War, had speculated about building a "fighting-machine" or a "land dreadnought". Wells later further explored the ideas of an armoured fighting vehicle in his short story "The Land Ironclads".[26] There is a high level of science-fiction abstraction in Wells' description of Martian automotive technology, he stresses how Martian machinery is devoid of wheels, using the "muscle-like" contractions of metal discs along an axis to produce movement.

Ecology

Wells' dramatization of an ecological threat posed by a rapidly growing alien organism, the Red Weed, which spreads over the English landscape, also has parallels in more modern times. Non-native species such as rabbits and prickly pear have been introduced into the Australian landscape, with a damaging impact. Another example is the spread of Kudzu in the United States.[13] However, these species were not introduced with the intention of causing deliberate harm.

Interpretations

Natural selection

H.G. Wells was a student of Thomas Henry Huxley, who was a major influence upon him. Huxley was commonly referred to as 'Darwin's bulldog'. This was as a result of his vigorous defense of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection against criticism by the Victorian religious establishment during the later half of the nineteenth century. They saw the theory of natural selection as an attempt to suggest that the development of life on earth did not require any kind of supernatural explanation such as a divine creator. Darwin's theory suggested that every species was competing to survive in a given environment and the species which had evolved the most useful biological adaptions to that environment, was most likely to survive and produce offspring also possessing these useful characteristics.[27]

In the novel, the conflict between humankind and the Martians is portrayed as a similar struggle. It is a survival of the fittest, with the Martians whose longer period of successful evolution on the older Mars, has led to them developing a superior intelligence, able to create weapons far in advance of humans on the younger planet Earth, who have not had the opportunity to develop sufficient intelligence to construct similar weapons. [28]

Human evolution

The novel also suggests a potential future for human evolution and perhaps a warning against overvaluing intelligence against more human qualities. The Narrator describes the Martians as having evolved an overdeveloped brain, which has left them with cumbersome bodies, with increased intelligence, but a diminished ability to use their emotions, something Wells attributes to bodily function. The Narrator refers to an 1893 publication suggesting that the evolution of the human brain might outstrip the development of the body, and organs such as the stomach, nose, teeth and hair would wither, leaving humans as thinking machines, needing mechanical devices much like the Tripod fighting machines, to be able to interact with their environment. This publication is probably Wells's own "The Man of the Year Million", published in the Pall Mall Gazette on November 6, 1893, which suggests similar ideas.[29][30]

Colonialism and imperialism

At the time of the Novel's publication the British Empire was in its most aggressive phase of expansion, having conquered and colonized dozens of territories in Africa, Australia, South America, the Middle East, South East Asia, and Atlantic and Pacific islands. It was one of a number of European empires, whose competition to conquer other nations eventually lead to the First World War.[12]

While Invasion Literature had provided an imaginative foundation for the idea of the heart of the British Empire being conquered by foreign forces, it was not until The War of the Worlds, that the reading public of the time were presented with an adversary so completely superior to themselves and the Empire they were part of.[31] A significant motivating force behind the success of The British Empire was its use of sophisticated technology; the Martians, also attempting to establish an empire on Earth, have technology superior to their British adversaries.[32] In writing The War of the Worlds, Wells turned the confident position of a reader in the British Empire on its head, putting an imperial power in the position of being the victim of imperial aggression and thus perhaps encouraging the reader to consider the nature of imperialism itself.[31]

Wells suggests this idea in the following passage from the novel:

And before we judge them [the Martians] too harshly, we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished Bison and the Dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

— Chapter I, "The Eve of the War"

This also challenged the Victorian notion of there being a natural order, in which the British Empire had a right to rule through their own superiority over subject races.[31]

Social Darwinism

The novel also dramatizes the ideas of race presented in Social Darwinism, an ideology of some prominence at the time it was written. The Martians exercise over humans their 'rights' as a superior race, more advanced in evolution. [33]

Social Darwinism was a theory which applied Darwin's theory of Natural Selection to ethnic groups and social classes. It suggested that the success of these different ethnic groups in world affairs, and social classes in a society were the result of evolutionary forces, a struggle in which the group or class more fit to succeed did so; ie, the ability of an ethnic group to dominate other ethnic groups, or the chance to succeed or rise to the top of society was determined by biology, not by the effort of individuals, and the offspring of the dominant groups were destined to succeed because they were more evolved. In more modern times it is typically seen as dubious and unscientific for its apparent use of Darwin's ideas to justify the position of the rich and powerful, or dominant ethnic groups. It was a theory exploited by the Nazis to justify their actions, was at one time used to justify the repression of women, and even used to justify sterilizing people thought to belong to an inferior type.[34]

Wells was born into a family which, while middle class, was not well to do and matured in a society where the merit of an individual was not considered as important as their social class of origin. His father was a professional sportsman, which was seen as inferior, because this was an area that 'gentlemen' only indulged in as an amateur pastime. His mother was at one time a domestic servant, and Wells himself was, prior to his writing career, apprenticed to a draper. His achievements were hard won. Trained as a scientist, well aware of evolutionary theory, he was able to relate his experiences of struggle to Darwin's idea of a world of struggle, but he saw science as a rational system, which extended beyond traditional ideas of race, class and religious notions, and this gave his fiction a critical edge which challenged the use of science to explain political and social norms of the day.[35]

Religion and science

In keeping with the rational scientific outlook of the novel, good and evil appear to be entirely relative in The War of the Worlds, and the defeat of the Martians does not involve any kind of divine power. It is as a result of an entirely material cause, the action of microscopic bacteria. An insane clergyman is a key character in the novel, but his attempts to relate the invasion to some kind of biblical enactment of Armageddon seem only to reinforce his mental derangement.[30] His death, as a result of his evangelical outbursts and ravings attracting the attention of the Martians, appears to be an indictment of his outdated religious attitudes making him a candidate for culling by natural selection, at the hands of the superior evolved Martians.[36]

Influences

Mars and Martians

The novel originated several enduring Martian tropes in science fiction writing. These include Mars being an ancient world, nearing the end of its life, being the home of a superior civilization, capable of advanced feats of science and engineering, and also being a source of invasion forces, keen to conquer the Earth. The first two tropes were prominent in Edgar Rice Burroughs "Barsoom" series, beginning with A Princess of Mars in 1912.[6]

Influential scientist Freeman Dyson, a key figure in the search for extraterrestrial life, also acknowledges his debt to reading H.G. Wells' fictions as a child.[37]

The publication and reception of The War of the World's also established the vernacular term of 'martian', as a description for something offworldly or unknown.[38]

Aliens and alien invasion

Antecedents

Wells is credited with establishing several extraterrestrial themes which were later greatly expanded by science fiction writers in the 20th Century, including first contact and war between planets and their differing species. There were, however, stories of aliens and alien invasion prior to publication of The War of the Worlds.[39]

In 1727 Jonathan Swift published Gulliver's Travels. The tale included a race of beings similar but not identical to humanity, who are obsessed with mathematics and are superior to humans. They populate a floating island fortress called Laputa, four and one half miles in diameter, which uses its shadow to prevent sun and rain from reaching earthly nations over which it travels, ensuring they will pay tribute to the Laputians. [40] Voltaire's Micromégas (1752) includes two aliens, from Saturn and Sirius, who are of immense size and visit the Earth out of curiosity. At first they think the planet is uninhabited, due to the difference in scale between them and the peoples of Earth. When they discover the haughty Earth-centric views of Earth philosophers, they are greatly amused by how important Earth beings think they are compared to greater beings in the universe such as themselves. [41]

In 1892 Robert Potter, an Australian Clergyman, published The Germ Growers in London. It describes a covert invasion by aliens who take on the appearance of human beings and attempt to develop a virulent disease to assist in their plans for global conquest. It was not widely read, and consequently Wells' vastly more successful novel is generally credited as the seminal alien invasion story.[39]

The first science fiction to be set on Mars may be Across the Zodiac: The Story of a Wrecked Record, by Percy Greg, published in 1880. It was a long-winded book concerned with a civil war on Mars. Another Mars novel, although dealing with benevolent martians coming to Earth to give humankind the benefit of their advanced knowledge, was published in 1897 by Kurd Lasswitz, Two Planets (Auf Zwei Planeten). It was not translated until 1971, and thus may not have influenced Wells, although it did depict a Mars influenced by the ideas of Percival Lowell.[42] Other examples are Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet (1889), which took place on Mars, Gustavus W. Popes's Journey to Mars (1894), and Ellsworth Douglas's Pharaoh's Broker, in which the protagonist encounters an Egyptian civilization on Mars which, while parallel to that of the Earth has evolved somehow independently.[43]

Early examples of influence on science fiction

Wells had already proposed another outcome for the alien invasion story in The War of the Worlds. When the Narrator meets the artilleryman the second time, the artilleryman imagines a future where humanity, hiding underground in sewers and tunnels, conducts a guerrilla war, fighting against the Martians for generations to come, and eventually, after learning how to duplicate Martian weapon technology, destroys the invaders and takes back the Earth.[36]

Six weeks after publication of the novel, the Boston Post newspaper published another alien invasion story, an unauthorized sequel to The War of the Worlds, which turned the tables on the invaders. Edison's Conquest of Mars was written by Garrett P. Serviss, a now little remembered writer, who described the famous inventor Thomas Edison leading a counterattack against the invaders on their home soil.[13]. Though this is actually a sequel to 'Fighters from Mars', a revised and unauthorised reprint of War of the Worlds, they both were first printed in the Boston Post in 1898[44].

The War of the Worlds was reprinted in the United States in 1927, before the Golden Age of science fiction, by Hugo Gernsback in Amazing Stories. John W. Campbell, another key editor of the era, and periodic short story writer, published several alien invasion stories in the 1930s. Many well known science fiction writers were to follow, including Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clark, Clifford Simak and Robert A. Heinlein, with The Puppet Masters, in 1953. [15]

Later examples

The theme of alien invasion has remained popular to the present day, some more recent examples in science fiction literature being Footfall by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, the "Worldwar" series by Harry Turtledove, L. Ron Hubbard's Battlefield Earth and Orson Scott Card's Enders Game. Examples from television and film include the 1980s television miniseries and series V, the 1990s films Independence Day, Tim Burton's farcical Mars Attacks! and the television series the X-files.

Also, Alan Moore's graphic novel, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume II, retells the events in The War of the Worlds.

Tripods

Other narratives, in addition to utilizing the alien invasion trope, also involve the appearance of tripod alien fighting machines. The Tripods, a science fiction trilogy for young adults written in the late 1960s by John Christopher is perhaps the most prominent example. The books, which were later part dramatized by the BBC in the mid 1980s, depict an invasion by aliens known as 'The Masters', whose superior technology easily defeats modern armies. Set centuries later, human beings are subdued by pacifying mind control devices, and watched over by the aliens, who use Tripods as transport. The tripods give no clue as to the nature of their occupants, and are worshiped by the majority of humanity. They are eventually defeated by a rebellion using rediscovered Earth technology and human ingenuity. [45] John Christopher admitted (in a BBC documentary called The Cult of the Tripods) that the alien war machines were inspired, at least subconsciously, by The War of the Worlds.

The computer game Half-Life 2 is a more recent example, with an apparent homage to The War of the Worlds in the appearance of tripod fighting machines known as Striders used by the alien invaders.[46]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 052127804X.

- ^ a b Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0415159105.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1981). The Science Fiction of H.G. Wells. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-19-502812-0.

- ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. p. 239. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 052127804X.

- ^ a b c d Baxter, Stephen (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "H.G. Wells' Enduring Mythos of Mars". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 186–7. ISBN 1932100555.

- ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. p. 240. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ Martin, Christopher (1988). H.G. Wells. Wayland. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1-85210-489-9.

- ^ a b Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Speilberg. Galactic Books. pp. 12–19. ISBN 0976940000.

- ^ Pearson, Lynn F. (2006). Public Art Since 1950. Osprey Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 074780642X.

- ^ Lackey, Mercedes (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "In Woking's Image". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 216. ISBN 1932100555.

- ^ a b Franklin, H. Bruce (2008). War Stars. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 65. ISBN 1558496513.

- ^ a b c d Gerrold, David (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "War of the Worlds". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 202–205. ISBN 1932100555, 9781932100556.

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 0415159105.

- ^ a b Urbanski, Heather (2007). Plagues, Apocalypses and Bug-Eyed Monsters. McFarland. p. 156. ISBN 078642916X, 9780786429165.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) Cite error: The named reference "urbanski" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Aldiss, Brian W.; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree: the History of Science Fiction. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 123. ISBN 0-575-03943-4.

- ^ a b Eby, Cecil D. (1988). The Road to Armageddon: The Martial Spirit in English Popular Literature, 1870-1914. Duke University Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 0822307758.

- ^ a b c Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. CUP Archive. p. 7. ISBN 052127804X.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (2000). Learning from Other Worlds. Liverpool University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0853235848.

- ^ McConnell, Frank (1981). The Science Fiction of H.G. Wells. Oxford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-19-502812-0.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 368-9. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Seed, David (2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Publishing. p. 546. ISBN 1405112182.

- ^ Meadows, Arthur Jack (2007). The Future of the Universe. Springer. p. 5. ISBN 1852339462.

- ^ a b Gannon, Charles E. (2005). Rumours of War and Infernal Machines. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 99-100. ISBN 0742540359.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (1997). H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0415159105.

- ^ Landships: Armored Vehicles for Colonial-era Gaming

- ^ Williamson, Jack (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "The Evolution of the Martians". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 189–195. ISBN 1932100555, 9781932100556.

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Williamson, Jack (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "The Evolution of the Martians". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 189–195. ISBN 1932100555, 9781932100556.

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Haynes, Rosylnn D. (1980). H.G. Wells Discover of the Future. Macmillan. p. 129-131. ISBN 0-333-27186-6.

- ^ a b Draper, Michael (1987). H.G. Wells. Macmillan. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-333-40747-4.

- ^ a b c Zebrowski, George (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "The Fear of the Worlds". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 235–41. ISBN 1932100555.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 148. ISBN 0-333-97022-5.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (2000). Learning from Other Worlds. Liverpool University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0853235848.

- ^ McClellan, James Edward; Dorn, Harold (2006). Science and Technology in World History. JHU Press. pp. 378–90. ISBN 0801883601.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2006). The The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–44. ISBN 0-333-97022-5.

- ^ a b Batchelor, John (1985). H.G. Wells. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 052127804X.

- ^ Basalla, George (2006). Civilized Life in the Universe: Scientists on Intelligent Extraterrestrials. Oxford University Press US. p. 91. ISBN 0195171810, 9780195171815.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Silverberg, Robert (2005). Glenn Yeffeth (ed.). "Introduction". War of the Worlds: fresh perspectives on the H.G. Wells classic/ edited by Glenn Yeffeth. BenBalla: 12. ISBN 1932100555.

- ^ a b Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Speilberg. Galactic Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0976940000.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 300-301. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Guthke, Karl S. (1990). The Last Frontier: Imagining Other Worlds from the Copernican Revolution to Modern Fiction. Translated by Helen Atkins. Cornell University Press. pp. 301-304. ISBN 0-8014-1680-9.

- ^ Hotakainen, Markus (2008). Mars: A Myth Turned to Landscape. Springer. p. 205. ISBN 0387765077.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2000). Space and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Groups. p. 38. ISBN 0313308462.

- ^ Edison’s Conquest of Mars, "Forward" by Robert Godwin, Apogee Books 2005

- ^ Flynn, John L. (2005). War of the Worlds: From Wells to Spielberg. Galactic Books. pp. 169–173. ISBN 0976940000.

- ^ "Half Life 2". Gamecritics.com. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

External links

- The War of the Worlds Invasion Large resource containing comment and review on the history of The War of the Worlds.

- 2008 edition of The War of the Worlds includes artwork by Warwick Goble, commissioned by Pearsons Magazine in 1897, artwork by Alvim Corrêa for the L.Vandamme 500 copy limited edition in 1906 and cover art by Frank R. Paul, commissioned by Amazing Stories in 1927. Published by Engage Books.

- The War of the Worlds, complete text with embedded audio.

- The War of the Worlds at Project Gutenberg.

- The War of the Worlds as a bilingual ebook with English and Spanish side by side.

- Complete as-delivered transcript and entire original Mercury Theatre Radio broadcast AmericanRhetoric.com.

- TIME Archives A look at perceptions of The War of the Worlds over time.

- Hundreds of cover images of the book's different editions, from 1898 to now.

Bibliography

- Yeffeth, Glenn (Editor) (2005) The War of the Worlds: Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic. Publisher: Benbella Books ISBN 1932100555

- Coren, Michael (1993) The Invisible Man : The Life and Liberties of H.G. Wells. Publisher: Random House of Canada. ISBN 0394222520

- Roth, Christopher F. (2005) "Ufology as Anthropology: Race, Extraterrestrials, and the Occult." In E.T. Culture: Anthropology in Outerspaces, ed. by Debbora Battaglia. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.