Calvary

Calvary (Latin: Calvariae or Calvariae locus) or Golgotha (Biblical Greek: Γολγοθᾶ, romanized: Golgothâ) was a site immediately outside Jerusalem's walls where, according to Christianity's four canonical gospels, Jesus was crucified.[1]

Since at least the early medieval period, it has been a destination for pilgrimage. The exact location of Calvary has been traditionally associated with a place now enclosed within one of the southern chapels of the multidenominational Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a site said to have been recognized by the Roman empress Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, during her visit to the Holy Land in 325.

Other locations have been suggested: in the 19th century, Protestant scholars proposed a different location near the Garden Tomb on Green Hill (now "Skull Hill") about 500 m (1,600 ft) north of the traditional site and historian Joan Taylor has more recently proposed a location about 175 m (574 ft) to its south-southeast.[citation needed]

Biblical references and names

[edit]

The English names Calvary and Golgotha derive from the Vulgate Latin Calvariae, Calvariae locus and locum (all meaning "place of the Skull" or "a Skull"), and Golgotha used by Jerome in his translations of Matthew 27:33,[2] Mark 15:22,[3] Luke 23:33,[4] and John 19:17.[5] Versions of these names have been used in English since at least the 10th century,[6] a tradition shared with most European languages including French (Calvaire), Spanish and Italian (Calvario), pre-Lutheran German (Calvarie),[7][8] Polish (Kalwaria), and Lithuanian (Kalvarijos). The 1611 King James Version borrowed the Latin forms directly,[9] while Wycliffe and other translators anglicized them in forms like Caluarie,[6] Caluerie,[10] and Calueri[11] which were later standardized as Calvary.[12] While the Gospels merely identify Golgotha as a "place", Christian tradition has described the location as a hill or mountain since at least the 6th century. It has thus often been referenced as Mount Calvary in English hymns and literature.[13]

In the 1769 King James Version, the relevant verses of the New Testament are:

- And when they were come unto a place called Golgotha, that is to say, a place of a skull, They gave him vinegar to drink mingled with gall: and when he had tasted thereof, he would not drink. And they crucified him, and parted his garments, casting lots...[14]

- And they bring him unto the place Golgotha, which is, being interpreted, The place of a skull. And they gave him to drink wine mingled with myrrh: but he received it not. And when they had crucified him, they parted his garments, casting lots upon them, what every man should take.[15]

- And when they were come to the place, which is called Calvary, there they crucified him, and the malefactors, one on the right hand, and the other on the left.[16]

- And he bearing his cross went forth into a place called the place of a skull, which is called in the Hebrew Golgotha: Where they crucified him, and two other with him, on either side one, and Jesus in the midst.[17]

In the standard Koine Greek texts of the New Testament, the relevant terms appear as Golgothâ (Γολγοθᾶ),[18][19] Golgathân (Γολγοθᾶν),[20] kraníou tópos (κρανίου τόπος),[18] Kraníou tópos (Κρανίου τόπος),[20] Kraníon (Κρανίον),[21] and Kraníou tópon (Κρανίου τόπον).[19] Golgotha's Hebrew equivalent would be Gulgōleṯ (גֻּלְגֹּלֶת, "skull"),[22][23] ultimately from the verb galal (גלל) meaning "to roll".[24] The form preserved in the Greek text, however, is actually closer to Aramaic Golgolta,[25] which also appears in reference to a head count in the Samaritan version of Numbers 1:18,[26][27] although the term is traditionally considered to derive from Syriac Gāgūlṯā (ܓܓܘܠܬܐ) instead.[28][29][30][31][32] Although Latin calvaria can mean either "a skull" or "the skull" depending on context and numerous English translations render the relevant passages "place of the skull" or "Place of the Skull",[33] the Greek forms of the name grammatically refer to the place of a skull and a place named Skull.[24] (The Greek word κρᾱνῐ́ον does more specifically mean the cranium, the upper part of the skull, but it has been used metonymously since antiquity to refer to skulls and heads more generally.)[34]

The Fathers of the Church offered various interpretations of the name and its origin. Jerome considered it a place of execution by beheading (locum decollatorum),[13] Pseudo-Tertullian describes it as a place resembling a head,[35] and Origen associated it with legends concerning the skull of Adam.[13] This buried skull of Adam appears in noncanonical medieval legends, including the Book of the Rolls, the Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan, the Cave of Treasures, and the works of Eutychius, the 9th-century patriarch of Alexandria. The usual form of the legend is that Shem and Melchizedek retrieved the body of Adam from the resting place of Noah's ark on Mount Ararat and were led by angels to Golgotha, a skull-shaped hill at the center of the earth where Adam had previously crushed the serpent's head following the Fall of Man.[13]

In the 19th century, Wilhelm Ludwig Krafft proposed an alternative derivation of these names, suggesting that the place had actually been known as "Gol Goatha"—which he interpreted to mean "heap of death" or "hill of execution"—and had become associated with the similar sounding Semitic words for "skull" in folk etymologies.[36] James Fergusson identified this "Goatha" with the Goʿah (גֹּעָה)[37] mentioned in Jeremiah 31:39 as a place near Jerusalem,[38] although Krafft himself identified that location with the separate Gennáth (Γεννάθ) of Josephus, the "Garden Gate" west of the Temple Mount.[36]

Location

[edit]There is no consensus as to the location of the site. John 19:20 describes the crucifixion site as being "near the city". According to Hebrews 13:12, it was "outside the city gate". Matthew 27:39 and Mark 15:29 both note that the location would have been accessible to "passers-by". Thus, locating the crucifixion site involves identifying a site that, in the city of Jerusalem some four decades before its destruction in AD 70, would have been outside a major gate near enough to the city that the passers-by could not only see him, but also read the inscription 'Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews'.[39]

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

[edit]Christian tradition since the fourth century has favoured a location now within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This places it well within today's walls of Jerusalem, which surround the Old City and were rebuilt in the 16th century by the Ottoman Empire. Proponents of the traditional Holy Sepulchre location point to the fact that first-century Jerusalem had a different shape and size from the 16th-century city, leaving the church's site outside the pre-AD 70 city walls. Those opposing it doubt this.

Defenders of the traditional site have argued that the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was only brought within the city limits by Herod Agrippa (41–44), who built the so-called Third Wall around a newly settled northern district, while at the time of Jesus' crucifixion around AD 30 it would still have been just outside the city.

Henry Chadwick (2003) argued that when Hadrian's builders replanned the old city, they "incidentally confirm[ed] the bringing of Golgotha inside a new town wall."[40]

In 2007 Dan Bahat, the former City Archaeologist of Jerusalem and Professor of Land of Israel Studies at Bar-Ilan University, stated that "Six graves from the first century were found on the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. That means, this place [was] outside of the city, without any doubt…".[41]

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

[edit]

The traditional location of Golgotha derives from its identification by Queen Mother Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, in 325. Less than 45 meters (150 ft) away, Helena also identified the location of the tomb of Jesus and claimed to have discovered the True Cross; her son, Constantine, then built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre around the whole site. In 333, the author of the Itinerarium Burdigalense, entering from the east, described the result:

On the left hand is the little hill of Golgotha where the Lord was crucified. About a stone's throw from thence is a vault [crypta] wherein his body was laid, and rose again on the third day. There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica; that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty.[42]

Various archeologists have proposed alternative sites within the Church as locations of the crucifixion. Nazénie Garibian de Vartavan argued that the now-buried Constantinian basilica’s altar was built over the site.[43]

Temple to Aphrodite

[edit]

Prior to Helena's identification, the site had been a temple to Aphrodite. Constantine's construction took over most of the site of the earlier temple enclosure, and the Rotunda and cloister (which was replaced after the 12th century by the present Catholicon and Calvary chapel) roughly overlap with the temple building itself; the basilica church Constantine built over the remainder of the enclosure was destroyed at the turn of the 11th century, and has not been replaced. Christian tradition claims that the location had originally been a Christian place of veneration, but that Hadrian had deliberately buried these Christian sites and built his own temple on top, on account of his alleged hatred for Christianity.[44]

There is certainly evidence that c. 160, at least as early as 30 years after Hadrian's temple had been built, Christians associated it with the site of Golgotha; Melito of Sardis, an influential mid-2nd century bishop in the region, described the location as "in the middle of the street, in the middle of the city",[45] which matches the position of Hadrian's temple within the mid-2nd century city.

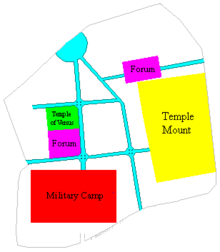

The Romans typically built a city according to a Hippodamian grid plan – a north–south arterial road, the Cardo (which is now the Suq Khan-ez-Zeit), and an east–west arterial road, the Decumanus Maximus (which is now the Via Dolorosa).[46] The forum would traditionally be located on the intersection of the two roads, with the main temples adjacent.[46] However, due to the obstruction posed by the Temple Mount, as well as the Tenth Legion encampment on the Western Hill, Hadrian's city had two Cardo, two Decumanus Maximus, two forums,[46] and several temples. The Western Forum (now the Muristan) is located on the crossroads of the West Cardo and what is now El-Bazar/David Street, with the Temple of Aphrodite adjacent, on the intersection of the Western Cardo and the Via Dolorosa. The Northern Forum is located north of the Temple Mount, on the junction of the Via Dolorosa and the Eastern Cardo (the Tyropoeon), adjacent to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, intentionally built atop the Temple Mount.[47] Another popular holy site that Hadrian converted to a pagan temple was the Pool of Bethesda, possibly referenced to in the fifth chapter of the Gospel of John,[48][49] on which was built the Temple of Asclepius and Serapis. While the positioning of the Temple of Aphrodite may be, in light of the common Colonia layout, entirely unintentional, Hadrian is known to have concurrently built pagan temples on top of other holy sites in Jerusalem as part of an overall "Romanization" policy.[50][51][52][53][54]

Archaeological excavations under the Church of the Holy Sepulchre have revealed Christian pilgrims' graffiti, dating from the period that the Temple of Aphrodite was still present, of a ship, a common early Christian symbol[55][56][57] and the etching "DOMINVS IVIMVS", meaning "Lord, we went",[58][59] lending possible support to the statement by Melito of Sardis' asserting that early Christians identified Golgotha as being in the middle of Hadrian's city, rather than outside.

Rockface

[edit]

During 1973–1978 restoration works and excavations inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and under the nearby Muristan, it was found that the area was originally a quarry, from which white Meleke limestone was struck;[60] surviving parts of the quarry to the north-east of the chapel of St. Helena are now accessible from within the chapel (by permission). Inside the church is a rock, about 7 m long by 3 m wide by 4.8 m high,[60] that is traditionally believed to be all that now remains visible of Golgotha; the design of the church means that the Calvary Chapel contains the upper foot or so of the rock, while the remainder is in the chapel beneath it (known as the tomb of Adam). Virgilio Corbo, a Franciscan priest and archaeologist, present at the excavations, suggested that from the city the little hill (which still exists) could have looked like a skull.[61]

During a 1986 repair to the floor of the Calvary Chapel by the art historian George Lavas and architect Theo Mitropoulos, a round slot of 11.5 cm (4.5 in) diameter was discovered in the rock, partly open on one side (Lavas attributes the open side to accidental damage during his repairs);[62] although the dating of the slot is uncertain, and could date to Hadrian's temple of Aphrodite, Lavas suggested that it could have been the site of the crucifixion, as it would be strong enough to hold in place a wooden trunk of up to 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) in height (among other things).[63][64] The same restoration work also revealed a crack running across the surface of the rock, which continues down to the Chapel of Adam;[62] the crack is thought by archaeologists to have been a result of the quarry workmen encountering a flaw in the rock.[citation needed]

Based on the late 20th century excavations of the site, there have been a number of attempted reconstructions of the profile of the cliff face. These often attempt to show the site as it would have appeared to Constantine. However, as the ground level in Roman times was about 4–5 feet (1.2–1.5 m) lower and the site housed Hadrian's temple to Aphrodite, much of the surrounding rocky slope must have been removed long before Constantine built the church on the site. The height of the Golgotha rock itself would have caused it to jut through the platform level of the Aphrodite temple, where it would be clearly visible. The reason for Hadrian not cutting the rock down is uncertain, but Virgilio Corbo suggested that a statue, probably of Aphrodite, was placed on it,[65] a suggestion also made by Jerome. Some archaeologists have suggested that prior to Hadrian's use, the rock outcrop had been a nefesh – a Jewish funeral monument, equivalent to the stele.[66]

Pilgrimages to Constantine's Church

[edit]

The Itinerarium Burdigalense speaks of Golgotha in 333: "... On the left hand is the little hill of Golgotha where the Lord was crucified. About a stone's throw from thence is a vault (crypta) wherein His body was laid, and rose again on the third day. There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica, that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty",[67] Cyril of Jerusalem, a distinguished theologian of the early Church, and eyewitness to the early days of Constantine's edifice, speaks of Golgotha in eight separate passages, sometimes as near to the church where he and his listeners assembled:[68] "Golgotha, the holy hill standing above us here, bears witness to our sight: the Holy Sepulchre bears witness, and the stone which lies there to this day."[69] And just in such a way the pilgrim Egeria often reported in 383: "… the church, built by Constantine, which is situated in Golgotha…"[70] and also bishop Eucherius of Lyon wrote to the island presbyter Faustus in 440: "Golgotha is in the middle between the Anastasis and the Martyrium, the place of the Lord's passion, in which still appears that rock which once endured the very cross on which the Lord was."[71] Breviarius de Hierosolyma reports in 530: "From there (the middle of the basilica), you enter into Golgotha, where there is a large court. Here the Lord was crucified. All around that hill, there are silver screens."[72] (See also: Eusebius in 338.[73])

Gordon's Calvary

[edit]

In 1842, Otto Thenius, a theologian and biblical scholar from Dresden, Germany, was the first to publish a proposal that the rocky knoll north of Damascus Gate was the biblical Golgotha.[74][75] He relied heavily on the research of Edward Robinson.[75] In 1882–83, Major-General Charles George Gordon endorsed this view; subsequently the site has sometimes been known as Gordon's Calvary. The location, usually referred to today as Skull Hill, is beneath a cliff that contains two large sunken holes, which Gordon regarded as resembling the eyes of a skull. He and a few others before him believed that the skull-like appearance would have caused the location to be known as Golgotha.[76]

Nearby is an ancient rock-cut tomb known today as the Garden Tomb, which Gordon proposed as the tomb of Jesus. The Garden Tomb contains several ancient burial places, although the archaeologist Gabriel Barkay has proposed that the tomb dates to the 7th century BC and that the site may have been abandoned by the 1st century.[77]

Eusebius comments that Golgotha was in his day (the 4th century) pointed out north of Mount Zion.[78] While Mount Zion was used previously in reference to the Temple Mount itself, Josephus, the first-century AD historian who knew the city as it was before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, identified Mount Zion as being the Western Hill (the current Mount Zion),[79][80] which is south of both the Garden Tomb and the Holy Sepulchre. Eusebius' comment therefore offers no additional argument for either location.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Vulgate, Matthaeum 27:33. (Latin)

- ^ Vulgate, Marcum 15:22. (Latin)

- ^ Vulgate, Lucam 23:33. (Latin)

- ^ Vulgate, Ioannem 19:17. (Latin)

- ^ a b Đa Halgan Godspel, Lucas 23:33. (Thorpe ed.)

- ^ Cf. Bavarian State Library MS. Rar. 880 (1494), Lucas 23:33. (German)

- ^ After Martin Luther's 1522 translation, it has been more common to translate the meaning of the Greek name directly into German as Schädelstätte, equivalent to "Skullplace".

- ^ KJV, Matthew 27:33, Marke 15:22, Luke 23:33, John 19:17. (1611 ed.)

- ^ Wycliffe, Maþeu 23:33, Luke 23:33, Joon 19:17.

- ^ Wycliffe, Mark 15:22.

- ^ Tyndale, Luke 23:33.

- ^ a b c d "Mount Calvary". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. III. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1908.

- ^ KJV, Matthew 27:33–35. (1769 ed.)

- ^ KJV, Mark 15:22–24. (1769 ed.)

- ^ KJV, Luke 23:33. (1769 ed.)

- ^ KJV, John 19:17–18. (1769 ed.)

- ^ a b Nestle, Maththaion 27:33. (Greek)

- ^ a b Iōanēn 19:17. (Greek)

- ^ a b Nestle, Markon 15:22. (Greek)

- ^ Nestle, Loukan 23:33. (Greek)

- ^ Lande, George M. (2001) [1961]. Building Your Biblical Hebrew Vocabulary Learning Words by Frequency and Cognate. Resources for Biblical Study 41. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 115. ISBN 1-58983-003-2 – via sbl-site.org.

- ^ "H1538 - gulgoleth - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (KJV)". blueletterbible.org.

- ^ a b "The Name Golgotha". Abarim Publications..

- ^ Alexander, Joseph Addison (1863), The Gospel According to Mark (3rd ed.), New York: Charles Scribner, p. 420.

- ^ Lightfoot, John (1822), The Harmony, Chronicle, and Order of the New Testament..., London: J.F. Dove, p. 164.

- ^ Louw, J.P.; et al. (1996), Greek–English Lexicon of the New Testament, United Bible Societies, p. 834.

- ^ Schultens, Albert (1737). Institutiones ad fundamenta linguæ Hebrææ: quibus via panditur ad ejusdem analogiam restituendam, et vindicandam: in usum collegii domestici (in Latin). Johannes Luzac. p. 334.

- ^ Thrupp, Joseph Francis (1855). Ancient Jerusalem: A New Investigation Into the History, Topography and Plan of the City, Environs, and Temple, Designed Principally to Illustrate the Records and Prophecies of Scripture. Macmillan & Company. p. 272.

- ^ Audo, Toma, ed. (2008) [1897-[1901]]. Treasure of the Syriac Language: A Dictionary of Classical Syriac. Vol. 1. Mosul; Piscataway, New Jersey: Imprimerie des pères dominicains. p. 117 – via dukhrana.com.

- ^ Payne Smith, Robert (1879). "Golgotha". Thesaurus Syriacus. Vol. 1. Oxford: The Calerndon Press. p. 324 – via dukhrana.com.

- ^ Payne Smith, J. (Mrs. Margoliouth) (1903). "Golgotha". A Compendious Syriac Dictionary. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 60 – via dukhrana.com.

- ^ Cf. e.g., the various translations of Matthew 27:33 at Biblehub.com.

- ^ "κρανίον, τό". Perseus Project.

- ^ Five Books in Reply to Marcion, Book 2, Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 4, p. 276.

- ^ a b Krafft, Wilhelm Ludwig (1846), Die Topographie Jerusalems [The Topography of Jerusalem], Bonn. (German)

- ^ "H1601: Goah", Strong's Concordance.

- ^ Fergusson, James (1847), An Essay on the Ancient Topography of Jerusalem, J. Weale, pp. 80-81, ISBN 9780524050347.

- ^ John 19:20

- ^ Chadwick, H. (2003). The Church in Ancient Society: From Galilee to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-926577-1.

- ^ Dan Bahat in German television ZDF, April 11, 2007

- ^ Itinerarium Burdigalense, pp. 593, 594

- ^ Garibian de Vartavan, N. (2008). La Jérusalem Nouvelle et les premiers sanctuaires chrétiens de l'Arménie. Méthode pour l'étude de l'église comme temple de Dieu. London: Isis Pharia. ISBN 978-0-9527827-7-3.

- ^ Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 3:26

- ^ Melito of Sardis, On Easter

- ^ a b c Ball, Warwick. Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 294.

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. Archaeological researches in Palestine during the years 1873–1874.

- ^ John 5:1–18

- ^ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, The Holy Land, (2008), p. 29

- ^ Peter Schäfer (2003). The Bar Kokhba war reconsidered: new perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (22 February 2007). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1996). "Judaism to Mishnah: 135–220 C.E". In Hershel Shanks (ed.). Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism: A Parallel History of their Origins and Early Development. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 196.

- ^ Emily Jane Hunt, Christianity in the second century: the case of Tatian, p. 7, at Google Books, Psychology Press, 2003, p. 7

- ^ E. Mary Smallwood The Jews under Roman rule: from Pompey to Diocletian, a study in political relations, p. 460, at Google Books Brill, 1981, p. 460.

- ^ Nave New Advent encyclopedia, accessed 25 March 2014.

- ^ Ship as a Symbol of the Church (Bark of St. Peter) Jesus Walk, accessed 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Ship hangs in balance at Pella Evangelical Lutheran Church". Sidney (Montana) Herald. 10 June 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. Archaeological researches in Palestine during the years 1873–1874. p. 103.

- ^ followinghadrian (5 November 2014). "Exploring Aelia Capitolina, Hadrian's Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ a b Hesemann, Michael (1999). Die Jesus-Tafel (in German). Freiburg. p. 170. ISBN 3-451-27092-7.

- ^ Hesemann 1999, p. 170: "Von der Stadt aus muß er tatsächlich wie eine Schädelkuppe ausgesehen haben," and p. 190: a sketch; and p. 172: a sketch of the geological findings by C. Katsimbinis, 1976: "der Felsblock ist zu 1/8 unterhalb des Kirchenbodens, verbreitert sich dort auf etwa 6,40 Meter und verläuft weiter in die Tiefe"; and p. 192, a sketch by Corbo, 1980: Golgotha is distant 10 meters outside from the southwest corner of the Martyrion-basilica

- ^ a b George Lavas, The Rock of Calvary, published (1996) in The Real and Ideal Jerusalem in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Art (proceedings of the 5th International Seminar in Jewish Art), pp. 147–150

- ^ Hesemann 1999, pp. 171–172: "....Georg Lavas and ... Theo Mitropoulos, ... cleaned off a thick layer of rubble and building material from one to 45 cm thick that covered the actual limestone. The experts still argue whether this was the work of the architects of Hadrian, who aimed thereby to adapt the rock better to the temple plan, or whether it comes from 7th century cleaning....When the restorers progressed to the lime layer and the actual rock....they found they had removed a circular slot of 11.5 cm diameter".

- ^ Vatican-magazin.com, Vatican 3/2007, pp. 12/13; Vatican 3/2007, p. 11, here p. 3 photo No. 4, quite right, photo by Paul Badde: der steinere Ring auf dem Golgothafelsen.

- ^ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ Dan Bahat, Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?, in Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 1986

- ^ "Bordeaux Pilgrim – Text 7b: Jerusalem (second part)". Archived from the original on 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "St. Cyril of Jerusalem" (PDF). p. 51, note 313. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-16. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "Cyril, Catechetical Lectures, year 347, lecture X" (PDF). p. 160, note 1221. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-16. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Iteneraria Egeriae, ccel.org. Accessed February 25, 2024.

- ^ Letter To The Presbyter Faustus Archived 2008-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, by Eucherius. "What is reported, about the site of the city Jerusalem and also of Judaea"; Epistola Ad Faustum Presbyterum. "Eucherii, Quae fertur, de situ Hierusolimitanae urbis atque ipsius Iudaeae." Corpus Scriptorum Eccles. Latinorum XXXIX Itinera Hierosolymitana, Saeculi IIII–VIII, P. Geyer, 1898

- ^ Whalen, Brett Edward, Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, p. 40, University of Toronto Press, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4426-0199-4; Iteneraria et alia geographica, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 175 (Turnhout, Brepols 1965), pp. 109–112

- ^ "NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine – Christian Classics Ethereal Library".

- ^ Wilson, Charles W. (1906). Golgotha and The Holy Sepulchre. The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. pp. 103–20 – via archive.org.

- ^ a b Thenius, Otto (1842). "Golgatha et Sanctum Sepulchrum". Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie (in German) – via archive.org.

- ^ White, Bill (1989). A Special Place: The Story of the Garden Tomb.

- ^ Barkay, Gabriel (March–April 1986). "The Garden Tomb". Biblical Archaeology Review.

- ^ Eusebius, Onomasticon, 365

- ^ "Zion". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 19, 2021 – via britannica.com.

- ^ Zanger, Walter. "The Unknown Mount Zion" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2021 – via jewishbible.org.

External links

[edit]- Golgotha Rediscovered – proposes that Golgotha was outside Lions' Gate

- Polish Calvaries: Architecture as a Stage for the Passion of Christ

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Congregations of Mount Calvary". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Congregations of Mount Calvary". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.