Theistic Satanism

Theistic Satanism is the belief that Satan is a supernatural being or force that individuals may contact and supplicate to,[1][2] and represents loosely affiliated or independent groups and cabals which hold such a belief. Another characteristic of Theistic Satanism include the use of ceremonial magic.[3]

Unlike LaVeyan Satanism, as founded by Anton LaVey in the 1960s, theistic Satanism is theistic[3] as opposed to atheistic, believing that Satan (Hebrew: הַשָׂטָן ha-Satan, ‘the accuser’) is a real entity[3] rather than an archetype.

The history of theistic Satanism and assessments of its existence and prevalence in history is obscured by it having been grounds for execution at some times in the past, and people having been accused of Satanism who did not worship Satan, such as the witch trials in Early Modern Europe. Most theistic Satanism exists in relatively new models and ideologies, many of which claim not to be involved with the Abrahamic religions at all.[4]

Possible history

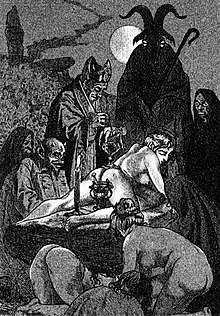

The worship of Satan was a frequent charge against those charged in the witch trials in Early Modern Europe and other witch-hunts such as the Salem witch trials. Worship of Satan was claimed to take place at the Witches' Sabbath.[5] The charge of Satan worship has also been made against groups or individuals regarded with suspicion, such as the Knights Templar, or minority religions.[6] In the case of the Knights Templar, the templars' writings mentioned the word 'baphomet', which was a French corruption of the name 'Mohammed' (the prophet of the people who the templars fought against), and that 'baphomet' was falsely portrayed as a demon by the people who accused the templars.

It is not known to what extent accusations of groups worshiping Satan in the time of the witch trials identified people who did consider themselves Satanists, rather than being the result of religious superstition or mass hysteria, or charges made against individuals suffering from mental illness. Confessions are unreliable, particularly as they were usually obtained under torture.[7] However, scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell, Professor Emeritus of the University of California at Santa Barbara, has made extensive arguments in his book Witchcraft in the Middle Ages[8] that not all witch trial records can be dismissed and that there is in fact evidence linking witchcraft to gnostic heresies. Russell comes to this conclusion after having studied the source documents themselves. Individuals involved in the Affair of the Poisons were accused of Satanism and witchcraft.

Historically, Satanist was a pejorative term for those with opinions that differed from predominant religious or moral beliefs.[9] Paul Tuitean believes the idea of acts of “reverse Christianity” was created by the Inquisition,[10] but George Bataille believes that inversions of Christian rituals such as the Mass may have existed prior to the descriptions of them which were obtained through the witchcraft trials.[11]

In the 18th century various kinds of popular “Satanic” literature began to be produced in France, including some well-known grimoires with instructions for making a pact with the Devil. Most notable are the Grimorium Verum and The Grand Grimoire. The Marquis de Sade describes defiling crucifixes and other holy objects, and in his novel Justine he gives a fictional account of the Black Mass,[12] although Ronald Hayman has said Sade's need for blasphemy was an emotional reaction and rebellion from which Sade moved on, seeking to develop a more reasoned atheistic philosophy.[13] In the 19th century, Eliphas Levi published his French books of the occult, and in 1855 produced his well-known drawing of the Baphomet which continues to be used by some Satanists today. That baphomet drawing is the basis of the sigil of Baphomet, which was first adopted by the non-theistic Satanist group called the Church of Satan.[14]

Finally, in 1891, Joris-Karl Huysmans published his Satanic novel, Là-bas, which included a detailed description of a Black Mass which he may have known first-hand was being performed in Paris at the time,[15] or the account may have been based on the masses carried out by Étienne Guibourg, rather than by Huysmans attending himself.[16] Quotations from Huysmans' Black Mass are also used in some Satanic rituals to this day since it is one of the few sources that purports to describe the words used in a Black Mass. The type of Satanism described in Là-bas suggests that prayers are said to the Devil, hosts are stolen from the Catholic Church, and sexual acts are combined with Roman Catholic altar objects and rituals, to produce a variety of Satanism which exalts the Devil and degrades the God of Christianity by inverting Roman Catholic rites. George Bataille claims that Huysman's description of the Black Mass is “indisputably authentic”.[11] Not all theistic Satanists today routinely perform the Black Mass, possibly because the mass is not a part of modern evangelical Christianity in Protestant countries[17] and so not such an unintentional influence on Satanist practices in those countries.

The earliest verifiable theistic Satanist group was a small group called the Ophite Cultus Satanas, which was created in Ohio in 1948. The Ophite Cultus Satanas was inspired by the ancient Ophite sect of Gnosticism, and the horned god of Wicca. The group was dependent upon its founder and leader, and therefore dissolved after his death in 1975.

Michael Aquino published a rare 1970 text of a Church of Satan black mass, the Missa Solemnis, in his book The Church of Satan,[18] and Anton LaVey included a different Church of Satan black mass, the Messe Noire, in his 1972 book The Satanic Rituals. LaVey's books on Satanism, which began in the 1960s, were for a long time the few available which advertised themselves as being Satanic, although others detailed the history of witchcraft and Satanism, such as The Black Arts by Richard Cavendish published in 1967 and the classic French work Satanism and Witchcraft, by Jules Michelet. Anton LaVey specifically denounced "devil worshippers" and the idea of praying to Satan.

Although non-theistic LaVey Satanism had been popular since the publication of The Satanic Bible in 1969, theistic Satanism did not start to gain any popularity until the emergence of the Order of Nine Angles in western England, and its publication of The Black Book of Satan in 1984.[citation needed] The next theistic Satanist group to be created was the Misanthropic Luciferian Order, which was created in Sweden in 1995. The MLO incorporated elements from the Order of Nine Angles, the Illuminates of Thanateros and Qliphothic Kabbalah.

Satanism and crime

The Satanic ritual abuse moral panic of the 1980s and 1990s was centered on fears or beliefs about traditional Satanism sacrificing children and committing crimes as part of rituals involving devil worship.[19] Allegations included the existence of large networks of organized Satanists involved in illegal activities such as murder, child pornography and prostitution; iconic cases such as the McMartin preschool trial were launched after children were repeatedly and coercively interrogated by social workers, resulting in false allegations of child sexual abuse. No evidence was ever found to support any of the allegations of Satanism or ritual abuse, but the panic resulted in numerous wrongful prosecutions.

John Allee, the creator of the LaVeyan website called First Church of Satan,[20] equates some of the "violent fringe" of Satanism with "Devil worshipers" and "reverse Christians". He believes they possibly suffer from a form of psychosis.[21] Between 1992 and 1996, some militant neo-pagans who were participants in the Norwegian black metal scene, such as Varg Vikernes,[22] committed over fifty arsons of Christian churches in and around Oslo as a retaliatory action against Christianity in Norway, but such church-burnings were widely attributed to Satanists.[23]

Some studies of crimes have also looked at the theological perspective of those who commit religious or ritualized crime.[24] Criminals who explain their crimes by claiming to be Satanists have been said by sociologists to be "pseudo-Satanists",[25] and attempts to link Satanism to crime have been seen by theistic Satanists as scaremongering.[26] In the 1980s and the 1990s there were multiple allegations of sexual abuse of children or non-consenting adults in the context of Satanic rituals in what has come to be known as the Satanic Panic. In the United States, the Kern County child abuse cases, McMartin preschool trial and the West Memphis 3 cases were widely reported. One case took place in Jordan, Minnesota, in which children made allegations of manufacturing child pornography, ritualistic animal sacrifice, coprophagia, urophagia and infanticide, at which point the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was alerted. Twenty-four adults were arrested and charged with acts of sexual abuse, child pornography and other crimes claimed to be related to Satanic ritual abuse; three went to trial, two were acquitted and one convicted. Supreme Court Justice Scalia noted in a discussion of the case that "[t]here is no doubt that some sexual abuse took place in Jordan; but there is no reason to believe it was as widespread as charged", and cited the repeated, coercive techniques used by the investigators as damaging to the investigation.[27]

Values in theistic Satanism

Seeking knowledge is seen by some theistic Satanists as being important to Satan, due to Satan being equated with the serpent in Genesis, which encouraged mankind to partake of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.[28] Some perceive Satan as Eliphas Levi's conception of Baphomet — a hermaphroditic bestower of knowledge (gnosis). Some Satanic groups, such as Luciferians, also seek to gain greater gnosis.[3] Some of such Satanists, such as the former Ophite Cultus Satanas, equate Yahweh with the demiurge of Gnosticism, and Satan with the transcendent being beyond.[3]

Self-development is important to theistic Satanists. This is due to the Satanists' idea of Satan, who is seen to encourage individuality and freedom of thought, and the quest to raise one's self up despite resistance, through means such as magic and initiative. They believe Satan wants a more equal relationship with his followers than the Abrahamic God does with his. From a theistic Satanist perspective, the Abrahamic religions (chiefly Christianity) do not define “good” or “evil” in terms of benefit or harm to humanity, but rather on the submission to or rebellion against God.[29] Some Satanists seek to remove any means by which they are controlled or repressed by others and forced to follow the herd, and reject non-governmental authoritarianism.[30]

As Satan in the Old Testament tests people, theistic Satanists may believe that Satan sends them tests in life in order to develop them as individuals. They value taking responsibility for oneself. Despite the emphasis on self-development, some theistic Satanists believe that there is a will of Satan for the world and for their own lives. They may promise to help bring about the will of Satan,[31] and seek to gain insight about it through prayer, study, or magic. In the Bible, a being called 'the prince of this world' is mentioned in 2 Corinthians 4:4, which Christians typically equate with Satan.[32] Some Satanists therefore think that Satan can help them meet their worldly needs and desires if they pray or work magic. They would also have to do what they could in everyday life to achieve their goals, however.

Theistic Satanists may try not to project an image that reflects negatively on their religion as a whole and reinforces stereotypes, such as promoting Nazism, abuse, or crime.[30] However, some groups, such as the Order of Nine Angles, criticize the emphasis on promoting a good image for Satanism; the ONA described LaVeyan Satanism as "weak, deluded and American form of 'sham-Satanic groups, the poseurs'",[33] and ONA member Stephen Brown claimed that "the Temple of Set seems intent only on creating a 'good public impression', with promoting an 'image'".[34] The order emphasises that its way "is and is meant to be dangerous"[35] and "[g]enuine Satanists are dangerous people to know; associating with them is a risk".[36] Similarly, the Temple of the Black Light has criticized the Church of Satan, and has stated that the Temple of Set is "trying to make Setianism and the ruler of darkness, Set, into something accepted and harmless, this way attempting to become a 'big' religion, accepted and acknowledged by the rest of the Judaeo-Christian society".[3] The TotBL rejects Christianity, Judaism and Islam as "the opposite of everything that strengthens the spirit and is only good for killing what little that is beautiful, noble and honorable in this filthy world".[3]

There is argument among Satanists over animal sacrifice, with most groups seeing it as both unnecessary and putting Satanism in a bad light, and distancing themselves from the few groups that practice it[which?], such as the Temple of the Black Light.[37]

Diversity of beliefs within theistic Satanism

The internet has increased awareness of different beliefs among Satanists, and led to more diverse groups. But Satanism has always been a pluralistic and decentralised religion.[38] Scholars outside Satanism have sought to study it by categorizing forms of it according to whether they are theistic or atheistic,[39] and referred to the practice of working with a literal Satan as traditional Satanism or theistic Satanism.[1] It is generally a prerequisite to being considered a theistic Satanist that the Satanist accept a theological and metaphysical canon involving one or more god(s) who are either Satan in the strictest, Abrahamic sense, or a concept of Satan that incorporates gods from other religions (usually pre-Christian), such as Ahriman or Enki. A small, now-defunct Satanist group called Children of the Black Rose equated Satan with the pantheistic the All.[40]

Many theistic Satanists believe their own individualized concept based on pieces of all these diverse conceptions of Satan, according to their inclination and spiritual guidance, rather than only believe in one suggested interpretation. Some may choose to live out the myths and stereotypes, but Christianity is not always the primary frame of reference for theistic Satanists.[41] Their religion may be based on dark pagan, left hand path and occult traditions. Theistic Satanists who base their faith on Christian ideas about Satan may be referred to as “reverse Christians” by other Satanists, often in a pejorative fashion.[42] However, those labeled by some as “reverse Christians” may see their concept of Satan as undiluted or sanitized. They worship a stricter interpretation of Satan: that of the Satan featured in the Christian Bible.[43] This is not, however, shared by a majority of theistic Satanists. Wiccans may consider most Satanism to be reverse Christianity,[44] and the head of the atheistic Church of Satan, Peter H. Gilmore, considers “devil worship” to be a Christian heresy, that is, a divergent form of Christianity.[45] The diversity of individual beliefs within theistic Satanism, while being a cause for intense debates within the religion, is also often seen as a reflection of Satan, who encourages individualism.[46]

A notable group that outwardly considers themselves to be traditional Satanists is the Order of Nine Angles.[47] This group became controversial and was mentioned in the press and in books, because they promoted human sacrifice.[48] The O9A believes that Satan is one of two 'acausal' eternal beings, the other one being Baphomet, and that Satan is male and Baphomet is female.

A group with very different ideology to the ONA is the Satanic Reds, whose Satanism has a communist element.[49] However, they are not theistic Satanist in the manner of believing in Satan as a god with a personality, but believe in dark deism,[50] the belief that Satan is a presence in nature. The First Church of Satan believe the philosophy propounded by Anton LaVey himself was deism or panentheism but is propounded as atheism by the leaders of the Church of Satan in order to distance themselves from what they see as pseudo-Satanists.[51]

One other group is the Temple of the Black Light, formerly known as the Misanthropic Luciferian Order prior to 2007. The group espouses a philosophy known as “Chaosophy”. Chaosophy asserts that the world that we live in, and the universe that it lives in, all exists within the realm known as Cosmos. Cosmos is made of three spatial dimensions and one linear time dimension. Cosmos rarely ever changes and is a materialistic realm. Another realm that exists is known as Chaos. Chaos exists outside of the Cosmos and is made of infinite dimensions and unlike the Cosmos, it is always changing. Members of the TotBL believe that the realm of Chaos is ruled over by 11 dark gods, the highest of them being Satan, and all of said gods are considered manifestations of a higher being. This higher being is known as Azerate, the Dragon Mother, and is all of the 11 gods united as one. The TotBL believes that Azerate will resurrect one day and destroy the Cosmos and let Chaos consume everything. The group has been connected to the Swedish black/death metal band Dissection, particularly its front man Jon Nödtveidt.[3] Nödtveidt was introduced to the group “at an early stage”.[52] The lyrics on the band's third album, Reinkaos, are all about beliefs of the Temple of the Black Light.[53] Nödtveidt committed suicide in 2006.[54][55]

Theistic Luciferian groups, such as the former Children of the Black Rose, are particularly inspired by Lucifer (from the Latin for ‘bearer of light’), who they may or may not equate with Satan. While some theologians believe the son of the dawn, Lucifer and other names were actually used to refer to contemporary political figures, such as a Babylonian King, rather than a single spiritual entity[56][57][58] (although on the surface the Bible explicitly refers to the King of Tyrus), those that believe it refers to Satan infer that by implication it also applies to the fall of Satan.[59] Joy of Satan believes that Satan appears angel-like; is the leader of the Nordic gods; is the ancient sumerian god Enki/Ea; and is the yezidi archangel called Melek Taus.[60] The Church of the Elders borrows its theology from Joy of Satan, believing that Satan is based upon Enki, but the Church of the Elders rejects calling this being 'Satan', instead calling it Enki, similar to how the Temple of Set believes that Satan is based upon Set, and should therefore be called Set rather than Satan. The Cathedral of the Black Goat believe Satan and Lucifer are the same being in his light and dark aspects.

Some writers equate the veneration of Set by the Temple of Set to theistic Satanism.[1] However, the Temple of Set do not identify as theistic Satanists. They believe the Egyptian deity Set is the real Dark Lord behind the name Satan, of whom Satan is just a caricature. Their practices primarily center on self-development. Within the temple of Set, the Black Flame is the individual's god-like core which is a kindred spirit to Set, and they seek to develop. In theistic Satanism, the Black Flame is knowledge which was given to humanity by Satan, who is a being independent of the Satanist himself[61] and which he can dispense to the Satanist who seeks knowledge.[62]

The diversity of beliefs amongst Satanists, and the theistic nature of some Satanists, was seen in a survey in 1995. Some spoke of seeing Satan not as someone dangerous to those who seek or worship him, but as someone that could be approached as a friend. Some refer to him as Father, though some other theistic Satanists consider that to be confused or excessively subservient.[63] However, in the Bible Satan is called the father of his followers in John 8:44, and bad people are called "children of the devil" in 1 John 3:10. Satan is also portrayed as a father to his daughter, Sin, by Milton in Paradise Lost.

Theistic Satanism often involves a religious commitment, rather than being simply an occult practice based on dabbling or transient enjoyment of the rituals and magic involved.[25][64] Practitioners may choose to perform a self-dedication rite, although there are arguments over whether it is best to do this at the beginning of their time as a theistic Satanist, or once they have been practicing for some time.[65]

See also

- Abrahamic religions

- Azazel

- Demonology

- Devil

- Dualism

- Folk religion

- God as the devil

- Left-hand path and right-hand path

- Luciferianism

- Magic (paranormal)

- Melek Taus

- Misotheism

- Moral panic

- Palladists

- Satanism

- Witchcraft

References

- ^ a b c Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 82. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Prayers to Satan". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Interview_MLO". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Servants of Satan". google.co.uk.

- ^ "Servants of Satan". google.co.uk.

- ^ "Servants of Satan". google.co.uk.

- ^ Witchcraft in the Middle Ages - Jeffrey Burton Russell - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Behrendt, Stephen C. (1983). The Moment of Explosion: Blake and the Illustration of Milton. U of Nebraska Press. p. 437. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Tuitean, Paul; Estelle Daniels (1998). Pocket Guide to Wicca. The Crossing Press. p. 22. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ a b Bataille, George (1986). Erotism: Death and Sensuality. Dalwood, Mary (trans.). City Lights. p. 126. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Sade, Donatien (2006). The Complete Marquis De Sade. Holloway House. pp. 157–158. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ Hayman, Ronald (2003). Marquis de Sade: The Genius of Passion. Tauris Parke. pp. 30–31. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ http://www.churchofsatan.com/images/church-of-satan-logo-black.png

- ^ Huysmans, Joris-Karl (1972). La Bas. Keene Wallace (trans.). Courier Dover. back cover. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Laver, James (1954). The First Decadent: Being the Strange Life of J.K. Huysmans. Faber and Faber. p. 121.

- ^ Christiano, Kevin; William H. Swatos; Peter Kivisto (2001). Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments. Rowman Altamira. p. 319. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Aquino, Michael (2002). The Church of Satan., Appendix 7.

- ^ Frankfurter, D (2006). Evil Incarnate: Rumors of Demonic Conspiracy and Ritual Abuse in History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11350-5.

- ^ "Answers - The Most Trusted Place for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.com.

- ^ "Is Devil Worship a Symptom of Psychosis? by High Priest John Allee". alleeshadowtradition.com.

- ^ [Moynihan, Michael and Soderlind, Didrik, Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground (2003), p. 220]

- ^ [Lords of Chaos, p. 89]

- ^ Yonke, David (2006). Sin, Shame, and Secrets: The Murder of a Nun, the Conviction of a Priest. p. 150. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ a b Gallagher, Eugene V. (2004). The New Religious Movements Experience in America. p. 190. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Dawn Perlmutter and her Institute for the Research of Organized and Ritual Violence". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836 (1990)

- ^ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 228. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Elliot Rose on "Evil"". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ a b Lewis, James R.; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2004). Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 446–447. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Mickaharic, Draja (1995). Practice of Magic: An Introductory Guide to the Art. Weiser. p. 62. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Ladd, George Eldon (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. p. 333. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Commentary on Dreamers of the Dark.

- ^ Stephen Brown: The Satanic Letters of Stephen Brown: St. Brown to Dr. Aquino (online version).

- ^ The True Way of the ONA.

- ^ Satanism: The Epitome of Evil.

- ^ "Animal Sacrifice and the Law". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ Lewis, James R.; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2004). Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 429. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Gallagher, Eugene V. (2004). The New Religious Movements Experience in America. Greenwood Publishing. p. 190. ISBN 0-313-32807-2.

- ^ Lewis, James R.; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2004). Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 438. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Lewis, James R.; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2004). Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 442. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ "Marburg Journal of Religion (June 2001) Lewis, James R." uni-marburg.de.

- ^ Archived Cathedral of the Black Goat 'Views' Page

- ^ Metzger, Richard; Grant Morrison (2003). Book of Lies: The Disinformation Guide to Magick and the Occult. The Disinformation Company. p. 266. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ High Priest, Magus Peter H. Gilmore. "Satanism: The Feared Religion". churchofsatan.com.

- ^ Susej, Tsirk (2007). The Demonic Bible. p. 11. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "The Religious Movements Homepage". virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006.

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2001). Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion. ABC-CLIO. p. 234. ISBN 1-57607-759-4.

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2001). Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion. ABC-CLIO. p. 240. ISBN 1-57607-759-4.

- ^ "DEVIL WORSHIP". theisticsatanism.com.

- ^ "SATANISM CENTRAL: Answers to All Your Questions". churchofsatan.org.

- ^ "Dissection. Interview with Jon Nödtveidt. June 2003". Metal Centre. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Official Dissection Website :: Reinkaos". Dissection.nu. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 22 April 2008 suggested (help) - ^ "Dissection Frontman Jon Nödtveidt Commits Suicide". Metal Storm. 18 August 2006. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Dissection Guitarist: Jon Nödtveidt Didn't Have Copy of 'The Satanic Bible' at Suicide Scene". Blabbermouth. 23 August 2006. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Lucifer King Of Babylon". realdevil.info.

- ^ Satan, Devil and Demons - Isaiah 14:12-14

- ^ "Apologetics Press - Is Satan "Lucifer"?". apologeticspress.org.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Devil". newadvent.org.

- ^ "Satan". angelfire.com.

- ^ Ford, Michael (2005). Luciferian Witchcraft. p. 373. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 82. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ Pike, Randall (2007). The Man with Confused Eyes. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 83. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Pacts and self-initiation". theisticsatanism.com.

Further reading

- Ellis, Bill, Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions and the Media (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000).

- Hertenstein, Mike; Jon Trott, Selling Satan: The Evangelical Media and the Mike Warnke Scandal (Chicago: Cornerstone, 1993).

- Brown, Seth; Think you're the only one? (Barnes & Noble Books 2004)

- Medway, Gareth J.; The Lure of the Sinister: The Unnatural History of Satanism (New York and London: New York University Press, 2001).

- Michelet, Jules, Satanism and Witchcraft: A Study in Medieval Superstition (English translation of 1862 French work).

- Palermo, George B.; Michele C. Del Re: Satanism: Psychiatric and Legal Views (American Series in Behavioral Science and Law) . Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd (November 1999)

- Pike, Albert, Morals and Dogma (1871)

- Richardson, James T.; Joel Best; David G. Bromley, The Satanism Scare (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1991).

- Vera, Diane, Theistic Satanism: The new Satanisms of the era of the Internet

- Karlsson, Thomas (February 2008). Qabalah, Qliphoth and Goetic Magic. ISBN 0-9721820-1-2.

- Ford, Michael (March 2005). Luciferian Witchcraft. ISBN 1-4116-2638-9.

- Baddeley, Gavin; Lucifer Rising, A Book of Sin, Devil Worship and Rock 'n' Roll (Plexus Publishing, November 1999)

- Webb, Don (March 1999). Uncle Setnakt's Essential Guide to the Left Hand Path. ISBN 1-885972-10-5.

- Zacharias, Gerhard (1980). The Satanic Cult. ISBN 0-04-133008-0. Translated from the German Satanskult und Schwarze Messe by Christine Trollope.